Soomaa National Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toimepiirkonnad Viljandi Maakonnas

TOIMEPIIRKONNAD VILJANDI MAAKONNAS Siseministeeriumi dokumendi „Juhend toimepiirkondade käsitlemiseks maakonnaplaneeringutes“ järgi JÄRELDUSED Mihkel Servinski Viljandi, 2014 1 ÜLESANNE Koostada Siseministeeriumi juhendi „Juhend toimepiirkondade käsitlemiseks maakonnaplaneeringutes“ (edaspidi Juhend) alusel ülevaade Viljandi maakonna võimalikest toimepiirkondadest ja tugi-toimepiirkondadest, võimalikest erinevate tasandite tõmbekeskustest ja määrata toimepiirkondade tsoonide geograafiline ulatud. JÄRELDUSED. Eestis on täna ühetasandiline kohaliku omavalitsuse süsteem. Kas Eesti jätkab ühe tasandilise kohaliku omavalitsussüsteemiga või mitte, on poliitiliste valikute küsimus ja sõltub sellest, milliste eesmärkide täitmist kohalikult omavalitsuselt oodatakse. Linnavalitsuste ja vallamajade asukoht ning neis lahendatavad ülesanded on Eesti arengu oluline teema, kuid kohaliku omavalitsuse süsteem on siiski vahend millegi saavutamiseks, mitte peamine strateegiline eesmärk. Sellest lähtuvalt võib öelda, et Raportis lahendatavate ülesannete seisukohalt on suhteliselt ükskõik, kus linnavalitsuse hoone või vallamaja paiknevad: kohaliku omavalitsuse teenus on üks paljudest avalikest teenustest ning sugugi mitte kõige elutähtsam. Eestis eksisteerib täna reaalselt mitmetasandiline tõmbekeskuste süsteem. Ei ole mingit võimalust, et Eesti muutuks ühetasandilise tõmbekeskuste süsteemiga riigiks või ühe tõmbekeskusega riigiks. Juhendi peamine vastuolu tekib sellest, et kui formaalselt käsitletakse Eestit mitmetasandilise tõmbekeskuste süsteemina, siis -

Country Background Report Estonia

OECD Review of Policies to Improve the Effectiveness of Resource Use in Schools Country Background Report Estonia This report was prepared by the Ministry of Education and Research of the Republic of Estonia, as an input to the OECD Review of Policies to Improve the Effectiveness of Resource Use in Schools (School Resources Review). The participation of the Republic of Estonia in the project was organised with the support of the European Commission (EC) in the context of the partnership established between the OECD and the EC. The partnership partly covered participation costs of countries which are part of the European Union’s Erasmus+ programme. The document was prepared in response to guidelines the OECD provided to all countries. The opinions expressed are not those of the OECD or its Member countries. Further information about the OECD Review is available at www.oecd.org/edu/school/schoolresourcesreview.htm Ministry of Education and Research, 2015 Table of Content Table of Content ....................................................................................................................................................2 List of acronyms ....................................................................................................................................................7 Executive summary ...............................................................................................................................................9 Introduction .........................................................................................................................................................10 -

EESTI GEOGRAAFIA SELTSI AASTARAAMAT 44. Köide

EESTI GEOGRAAFIA SELTSI AASTARAAMAT 44. köide ESTONIAN GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY YEARBOOK OF THE ESTONIAN GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY VOL. 44 Edited by Arvo Järvet TALLINN 2019 EESTI GEOGRAAFIA SELTSI AASTARAAMAT 44. KÖIDE Toimetanud Arvo Järvet TALLINN 2019 YEARBOOK OF THE ESTONIAN GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY VOL. 44 EESTI GEOGRAAFIA SELTSI AASTARAAMAT 44. KÖIDE Edited by: Arvo Järvet Toimetaja: Arvo Järvet Aastaraamatu väljaandmist on toetanud: Tartu ülikooli geograafia osakond Tallinna ülikooli ökoloogia keskus Eesti Maaülikooli Põllumajandus- ja keskkonnainstituut Autoriõigus: Eesti Geograafia Selts, 2019 ISSN 0202-1811 Eesti Geograafia Selts Kohtu 6 10130 Tallinn www.egs.ee Trükitud OÜ Vali Press SAATEKS Eesti geograafia tähistab tänavu olulist aastapäeva – 100 aastat tagasi detsembris 1919 alustas Tartu ülikool õppe- ja teadustööd rahvusülikoolina ning ühe uue üksusena alustas ülikoolis tegevust geograafiakabinet, mille juhendajaks oli TÜ esimene geograafia- professor Johannes Gabriel Granö. Paljud eesti geograafid võivad end tänapäevalgi kaudselt Granö õpilasiks lugeda – sedavõrd olu- line ja tulevikkusuunav oli tema ideede ja uurimismeetodite osa. Tartu ülikooli geograafia osakond on jäänud eesti geograafiateaduse ja kõrghariduse lipulaevaks tänaseni. Geograafiliste uuringutega on lisaks Tartu ülikoolile tegeletud ka teistes teadusasutustes: nõukogude perioodil rohkem Teaduste Aka- deemia majanduse ja geoloogia instituutides ning Tallinna botaanika- aias, Eesti Vabariigi iseseisvuse taastamise järel Eesti Maaülikoolis ja Tallinna ülikoolis. Geograafia -

Wood Pellet Damage

Wood pellet damage How Dutch government subsidies for Estonian biomass aggravate the biodiversity and climate crisis Sanne van der Wal July 2021 Colophon Wood pellet damage How Dutch government subsidies for Estonian biomass aggravate the biodiversity and climate crisis July 2021 Author: Sanne van der Wal Edit: Vicky Anning Layout: Frans Schupp Cover photo: Greenpeace / Karl Adami Stichting Onderzoek Multinationale This report is commissioned by Greenpeace Ondernemingen Netherlands Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations T: +31 (0)20 639 12 91 [email protected] www.somo.nl SOMO is a critical, independent, not-for- profit knowledge centre on multinationals. Since 1973 we have investigated multina- tional corporations and the impact of their activities on people and the environment. Wood pellet damage How Dutch government subsidies for Estonian biomass aggravate the biodiversity and climate crisis SOMO Sanne van der Wal Amsterdam, July 2021 Contents Summary ................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 7 1 Context ................................................................................................................ 8 1.1 Dutch Energy Agreement .................................................................................. 8 1.2 Wood pellet consumption in the Netherlands ........................................................ -

Reviewing the Coherence and Effectiveness of Implementation of Multilateral Biodiversity Agreements in Estonia

Stockholm Environment Institute Tallinn Centre, Publication No 25, Project Report – 2014 Reviewing the coherence and effectiveness of implementation of multilateral biodiversity agreements in Estonia Kaja Peterson, Piret Kuldna, Plamen Peev, Meelis Uustal Reviewing the coherence and effectiveness of implementation of multilateral biodiversity agreements in Estonia Kaja Peterson, Piret Kuldna, Plamen Peev, Meelis Uustal Reference: Peterson, K., Kuldna, P., Peev, P. and Uustal, M. 2014. Reviewing the coherence and effectiveness of implementation of multilateral biodiversity agreements in Estonia. Project Report, SEI Tallinn, Tallinn: 70 p. Project no 41064 Stockholm Environment Institute Tallinn Centre Lai Str 34 Tallinn 10133 Estonia www.seit.ee January–December 2013 Language editor: Stacey Noel, SEI Africa Lay-out: Tiina Salumäe, SEI Tallinn Photos: Kaja Peterson, SEI Tallinn ISBN: 978-9949-9501-4-0 ISSN: 1406-6637 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of acronyms and abbreviations ..................................................................................................................................................7 List of figures .............................................................................................................................................................................................8 List of tables ..............................................................................................................................................................................................8 Executive summary -

ENE INDERMITTE Exposure to Fluorides in Drinking Water

DISSERTATIONES GEOGRAPHICAE UNIVERSITATIS TARTUENSIS 41 DISSERTATIONES GEOGRAPHICAE UNIVERSITATIS TARTUENSIS 41 ENE INDERMITTE Exposure to fluorides in drinking water and dental fluorosis risk among the population of Estonia Department of Geography, Institute of Ecology and Earth Sciences, Faculty of Science and Technology, University of Tartu, Estonia This dissertation was accepted for the commencement of the degree of Doctor philosophiae in geography at the University of Tartu on June 7, 2010 by the Scientific Council of the Institute of Ecology and Earth Sciences of the University of Tartu Supervisors: Professor emeritus Astrid Saava, MD, dr.med. Department of Public Health, University of Tartu, Estonia Senior researcher Ain Kull, PhD Department of Geography, University of Tartu, Estonia Opponent: Ilkka Arnala, MD, PhD Head of Department of Orthopaedics Kanta-Häme Central Hospital, Finland Commencement: Scientific Council Hall, University of Tartu Main Building, 18 Ülikooli Street, Tartu, on 30 August 2010 at 2.15 p.m. Publication of this thesis has been funded by the Institute of Ecology and Earth Sciences of the University of Tartu and by the Doctoral School of Earth Sciences and Ecology created under the auspices of the European Social Fund. ISSN 1406–1295 ISBN 978–9949–19–424–7 (trükis) ISBN 978–9949–19–425–4 (PDF) Autoriõigus: Ene Indermitte, 2010 Tartu Ülikooli Kirjastus www.tyk.ee Tellimus nr. 358 CONTENTS LIST OF ORIGINAL PUBLICATIONS ...................................................... 7 Interactions between the papers .................................................................... -

Transnationalism in the Nordic-Baltic Region Hargmaisus Põhjala-Balti

Labour Mobility and Transationalism in the Nordic-Baltic Region 7 March 2014, Tallinn Transnationalism in the Nordic-Baltic Region Hargmaisus Põhjala-Balti piirkonnas Tiit Tammaru Professor of Population and Urban Geography Centre for Migration and Urban Studies Department of Geography University of Tartu www.cmus.ut.ee The world connected: global population networks http://news.utoronto.ca/diaspora-nation-economic- Author: Kamran Khan potential-networks#! Diasporas and transnational ties: Challenges Global security threat The new order of social inequalities Family members left behind Diasporas and transnational ties: Opportunities Alleviating social problems in the sending country Betterment of ones life chances Increased tolerance towards diversity Innovation diffusion: knowledge and skill transfer Opportunities can be better harnessed and challenges are easier to overcome within a regional context Outline of the talk Transnationalism: The concept Transnational institutional arrangements in the EU and in the Nordic-Baltic region Migration, cross-border commuting and return migration in the Nordic-Baltic region Policy challenges: A sending country perspective Transnationalism: The concept (as related to spatial mobility of people) Transnationalism (Glick Schiller et al. 1992; 2006; Vertovec 2005; Faist 2006; King et al. 2013) Transnationalism is most often defined as the outcome of the process by which immigrants link together their country of origin and their country of destination To be transnational means to belong to two or more -

Soomaa Rahvastik

SOOMAA RAHVASTIK Mihkel Servinski (Statistikaamet) Urmas Kase (Pärnu Maavalitsus) 1 Ülevaade kirjeldab Soomaa rahvastiku senist arengut ja mõtiskleb, milline võiks olla Soomaa rahvastiku edaspidine areng. Ülevaade on koostatud Soomaa teemaplaneeringu tarbeks Viljandi Maavalitsuse tellimusel. Ülevaate koostajad on Statistikaameti peaanalüütik Mihkel Servinski ja Pärnu Maavalitsuse arengutalituse juhataja Urmas Kase. Ülevaade on kirjutatud septembris 2013. SISUKORD Soomaast üldiselt - Soomaa hüpoteetilise vallana - Soomaa asulate kohast Pärnumaa ja Viljandimaa asustussüsteemis - Ettevõtlus Soomaal - Soomaa väravad Rahvaarv muutus Sünnid, surmad ja loomulik iive Soovanuskoosseis Soomaa rahvastikuarengu stsenaariumid - Kasvamine - Kahanemine - Kohanemine Kokkuvõte Mõisted. Metoodilised märkused Lisad. Soomaa külade rahvastikupassid Soomaa külade rahvastiku üheaastane soovanuskoosseis, 2000 Soomaa külade rahvastiku üheaastane soovanuskoosseis, 2011 Soomaa külade rahvastik vanuskoosseis valitud vanuserühmades, 1989, 2000, 2011. SOOMAAST ÜLDISELT Soomaa hüpoteetilise vallana Soomaad tuntakse Eestis eelkõige rahvuspargina. Käesoleva ülevaate kontekstis vaatleme Soomaad kahekümnest külast koosneva piirkonnana, mis asub viie valla (Kõpu, Pärsti (alates 5. novembrist 2013 on Pärsti vald osa Viljandi vallast, mis tekkis Paistu, Pärsti, Saarepeedi ja Viiratsi valla liitumisel), Suure-Jaani, Tori ja Vändra) ning kahe maakonna (Viljandi ja Pärnu) 2 territooriumil. Soomaa külad on Aesoo (Tori), Iia (Kõpu), Ivaski (Suure-Jaani), Kaansoo (Vändra), Karjaküla -

EUROPARC NBS Newsletter 1/2014

EUROPARC NBS Newsletter 1/2014 http://us4.campaign-archive1.com/?u=5108bdfadcd892894bfe63be6&... Subscribe Share Past Issues Translate Use this area to offer a short preview of your email's content. View this email in your browser Final countdown Ongoing year is the last presidency year for Estonia and Environmental Board. We are making our best to negotiate with possible next host of Nordic-Baltic Section secretariat. Many activities lie still ahead, such as interesting seminars about wooded grasslands and health issues. We rely on your good collaborations for the upcoming newsletters and other activities! Section secretariat 1 of 10 10.04.2014 9:34 EUROPARC NBS Newsletter 1/2014 http://us4.campaign-archive1.com/?u=5108bdfadcd892894bfe63be6&... Subscribe Share Past Issues Translate President´s corner Winter in Matsalu National Park was cold, Following species are getting special but very short. Spring migration has begun attention in Estonia this year having been with first grey-lag geese, lapwings and elected so called species of the year: sky-larks here; first hundreds of whooper Ringed Seal (Pusa hispida), Common and bewick's swans have started their Kingfisher (Alcedo atthis) and Alder song festival on Matsalu bay. Some of the Buckthorn (Rhamnus frangula). spring can be seen from home via internet - the "seal camera" of Vilsandi National In spite of good weather the mood is not Park is located in the grey-seals' kinder- very much so, the thoughts being held by garden: www.looduskalender.ee/node the tense situation in Ukraine. Who knows /19354 and "owl camera" of Matsalu how far the conflict can go, and there National Park is inside a tawny owl's nest: would be then losses both among people www.looduskalender.ee/node/19372 . -

Developing the Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) at Local Level - "DESI Local"

Developing the Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) at local level - "DESI local" Urban Agenda for the EU Partnership on Digital Transition Kaja Sõstra, PhD Tallinn, June 2021 1 1 Introduction 4 2 Administrative division of Estonia 5 3 Data sources for local DESI 6 4 Small area estimation 15 5 Simulation study 20 6 Alternative data sources 25 7 Conclusions 28 References 29 ANNEX 1 Population aged 15-74, 1 January 2020 30 ANNEX 2 Estimated values of selected indicators by municipality, 2020 33 Disclaimer This report has been delivered under the Framework Contract “Support to the implementation of the Urban Agenda for the EU through the provision of management, expertise, and administrative support to the Partnerships”, signed between the European Commission (Directorate General for Regional and Urban Policy) and Ecorys. The information and views set out in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the Commission. The Commission does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this report. Neither the Commission nor any person acting on the Commission’s behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained therein. 2 List of figures Figure 1 Local administrative units by the numbers of inhabitants .................................................... 5 Figure 2 DESI components by age, 2020 .......................................................................................... 7 Figure 3 Users of e-commerce by gender, education, and activity status ......................................... 8 Figure 4 EBLUP estimator of the frequent internet users indicator by municipality, 2020 ............... 17 Figure 5 EBLUP estimator of the communication skills above basic indicator by municipality, 2020 ....................................................................................................................................................... -

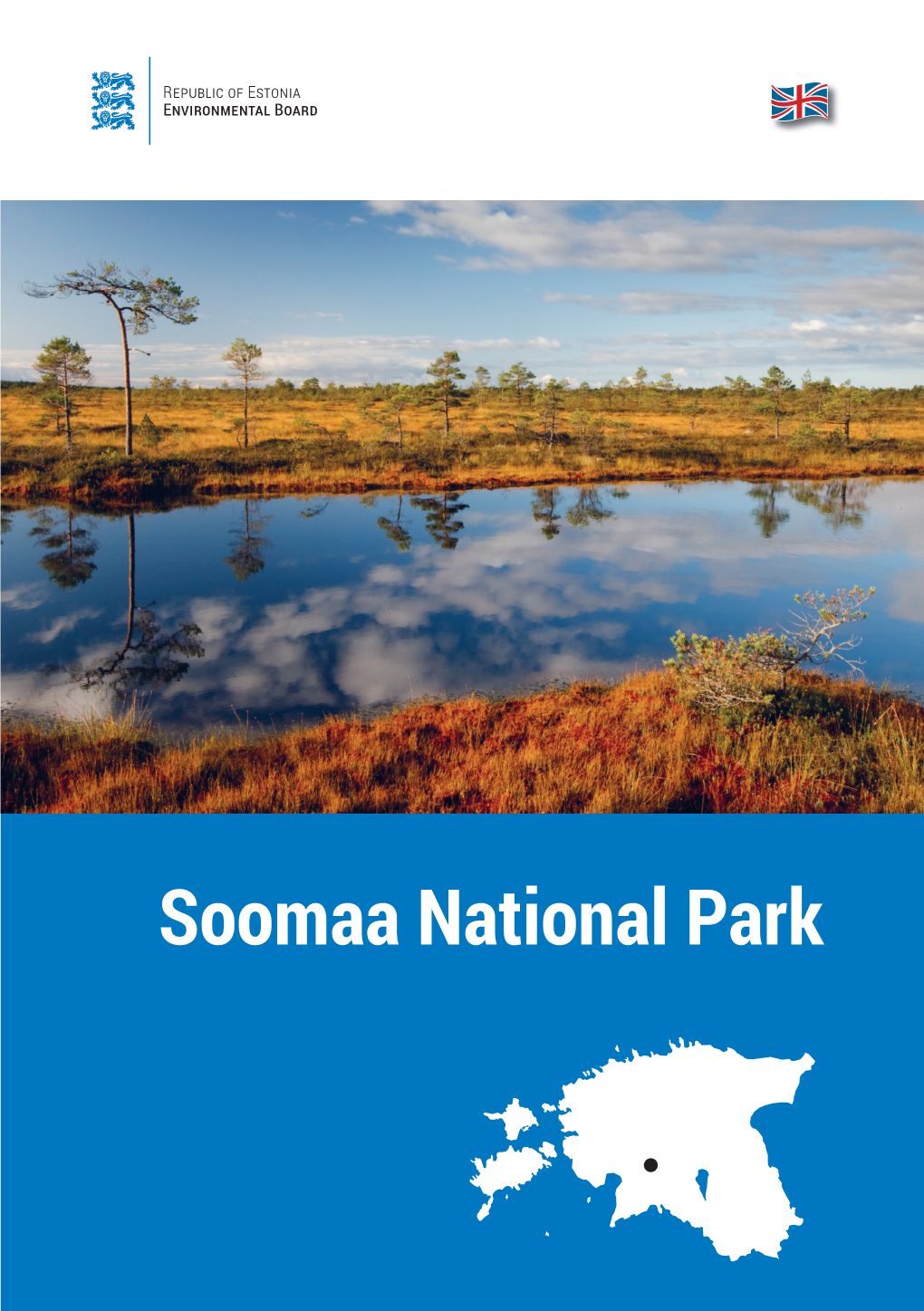

Wetland Tourism: Estonia - Soomaa National Park

A Ramsar Case Study on Tourism and Wetlands Wetland Tourism: Estonia - Soomaa National Park Estonia, Soomaa. Fifth Season in a Soomaa Boat. © Mati Kose Estonia’s Soomaa National Park is a Soomaa National Park is the most popular land of peat bogs, naturally meandering rivers, wilderness tourism destination of the Baltic swamp forests and meadows on the rivers’ countries. Its tourism products are based on floodplains. Its bogs and rivers began to develop wilderness experiences, the uniqueness of around 10,000 years ago when the last of the Soomaa and its cultural heritage, and the quality European ice sheets retreated northwards. Today services that are offered by the local tourism the area contains some of the best preserved and entrepreneurs and stakeholders. most extensive raised bogs in Europe. Each spring, it is subject to spectacular floods over a vast area – The Park was established under Estonian a time of the year that is known locally as the ‘fifth legislation in 1993, and joined the PAN Parks season’. Soomaa also has rich wildlife which Network of European wilderness areas in 2009. It includes golden eagles, black storks, woodpeckers, also received an EDEN (European Destinations of owls, various kinds of bog waders such as golden Excellence) award from the European Commission plovers, wood sandpipers, whimbrel, curlew, great in 2009 for promoting sustainable tourism in and snipe, and corn crake, as well as elk, wild boar, around a protected area. The site has been listed beaver, wolf, lynx, and brown bear. as a Ramsar Wetland of International Importance since 1997. The Ramsar Secretariat selected 14 case studies for a publication on wetlands and sustainable tourism, to be launched at the 11th Conference of Parties, July 2012. -

Vance D. Wolverton Chair Emeritus, Department of Music California

Vance D. Wolverton Chair Emeritus, Department of Music California State University, Fullerton [email protected] MART SAAR ESTONIAN COMPOSER & POET Consolidating the Past, Initiating the Future Vance D. Wolverton art Saar (1882-1963) was one of the most important Estonian Mcomposers of art music, espe- cially choral music, of the late nineteenth to mid-twentieth century. He lived and composed through a period of exponential political changes in Estonia—not altogether unlike the upheaval accompanying the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1990/91—including the fi rst period of independence (1918-1939), the fi rst period of Soviet occupation (1939-1941), the Nazi occupation (1941-1944), and nearly half of the second period of Soviet occupation (1944- 1991). It is common knowledge that the Soviets strongly discouraged participation in religious observations and activities, including the com- position of sacred music. It is also clear that such signifi cant disruptions to the political fabric of the nation were bound to infl uence all aspects of society, including music. Mart Saar lived and composed through these momentous times, and his compositions are refl ective of them. CHORAL JOURNAL Volume 57 Number 5 41 MART SAAR ESTONIAN COMPOSER & POET The Musical and Poetic Voice organist. He also edited the music journal “Muusikaleht.” of a Generation From 1943 to 1956, Saar was a professor of composition Along with his contemporary, Cyrillus Kreek (1889- at the Tallinn Conservatory. 1962), Mart Saar is considered one of the founders of Estonian professional music and its national style, espe- cially in the fi eld of choral music.