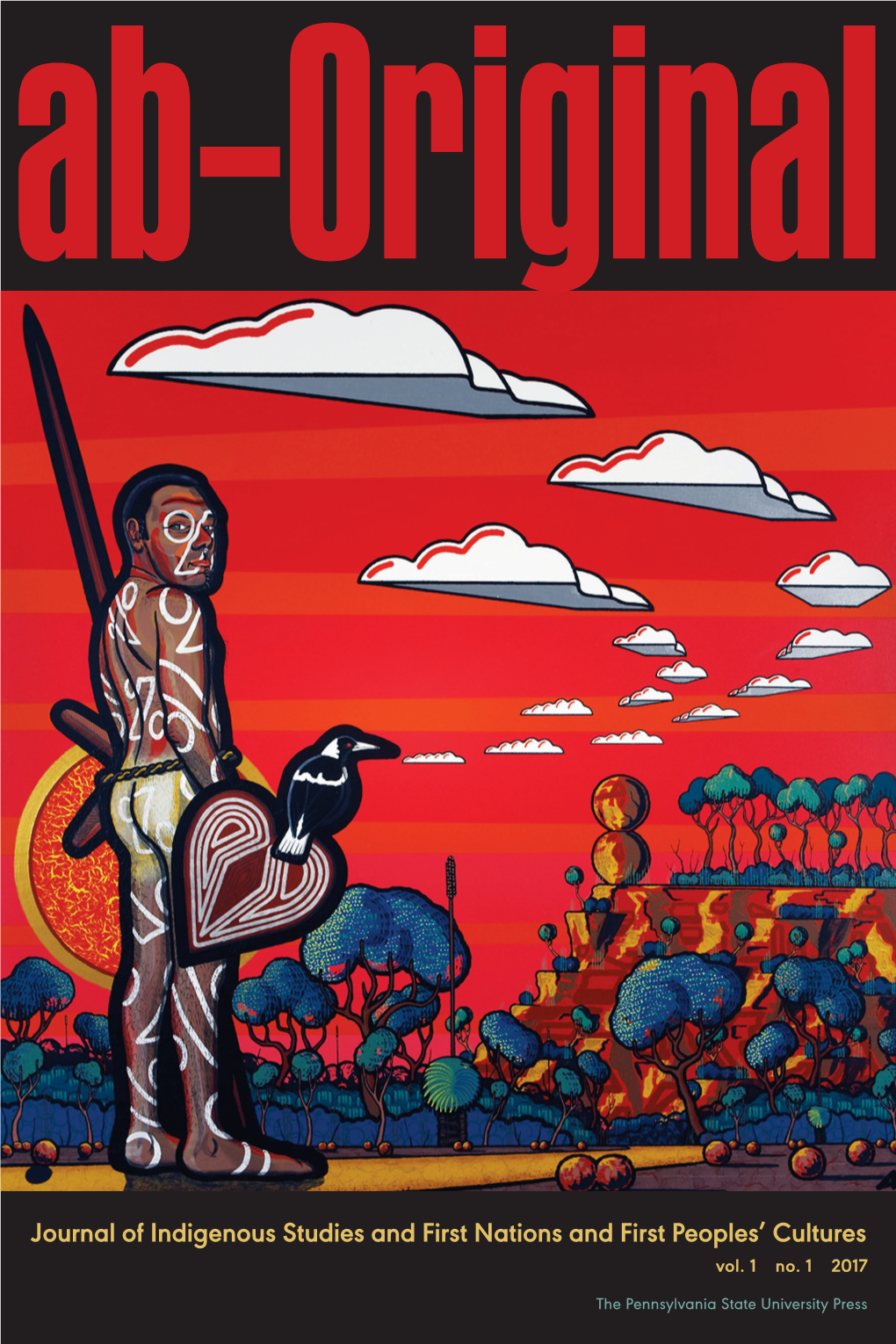

Journal of Indigenous Studies and First Nations and First Peoples’ Cultures Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian English: Its Evolution and Current State

International Journal of Language, Translation and Intercultural Communication Vol. 1, 2012 Australian English: Its Evolution and Current State Collins Peter University of New South Wales https://doi.org/10.12681/ijltic.11 Copyright © 2012 To cite this article: Collins, P. (2012). Australian English: Its Evolution and Current State. International Journal of Language, Translation and Intercultural Communication, 1, 75-86. doi:https://doi.org/10.12681/ijltic.11 http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 01/10/2021 02:29:09 | IJLTIC 2012 1 (1), 75-86 Articles | Oceania Australian English: Its Evolution and Current State Peter Collins, University of New South Wales, Australia Abstract his paper provides a critical overview of research on Australian English (‘AusE’), T and of the vexing questions that the research has grappled with. These include: What is the historical explanation for the homogeneity of the Australian accent? Was it formed by the fi rst generation of native-born Australians in the ‘Sydney mixing bowl’, its spread subsequently facilitated by high population mobility? Or is the answer to be found in sociolinguistic reconstructions of the early colony suggesting that a uniform London English was transplanted to Australia in 1788 and that speakers of other dialects quickly adapted to it? How is Australia’s national identity embodied in its lexicon, and to what extent is it currently under the infl uence of external pressure from American English? What are the most distinctive structural features of AusE phonology, -

German Lutheran Missionaries and the Linguistic Description of Central Australian Languages 1890-1910

German Lutheran Missionaries and the linguistic description of Central Australian languages 1890-1910 David Campbell Moore B.A. (Hons.), M.A. This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Social Sciences Linguistics 2019 ii Thesis Declaration I, David Campbell Moore, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text and, where relevant, in the Authorship Declaration that follows. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis contains published work and/or work prepared for publication, some of which has been co-authored. Signature: 15th March 2019 iii Abstract This thesis establishes a basis for the scholarly interpretation and evaluation of early missionary descriptions of Aranda language by relating it to the missionaries’ training, to their goals, and to the theoretical and broader intellectual context of contemporary Germany and Australia. -

Introduction

This item is Chapter 1 of Language, land & song: Studies in honour of Luise Hercus Editors: Peter K. Austin, Harold Koch & Jane Simpson ISBN 978-0-728-60406-3 http://www.elpublishing.org/book/language-land-and-song Introduction Harold Koch, Peter Austin and Jane Simpson Cite this item: Harold Koch, Peter Austin and Jane Simpson (2016). Introduction. In Language, land & song: Studies in honour of Luise Hercus, edited by Peter K. Austin, Harold Koch & Jane Simpson. London: EL Publishing. pp. 1-22 Link to this item: http://www.elpublishing.org/PID/2001 __________________________________________________ This electronic version first published: March 2017 © 2016 Harold Koch, Peter Austin and Jane Simpson ______________________________________________________ EL Publishing Open access, peer-reviewed electronic and print journals, multimedia, and monographs on documentation and support of endangered languages, including theory and practice of language documentation, language description, sociolinguistics, language policy, and language revitalisation. For more EL Publishing items, see http://www.elpublishing.org 1 Introduction Harold Koch,1 Peter K. Austin 2 & Jane Simpson 1 Australian National University1 & SOAS University of London 2 1. Introduction Language, land and song are closely entwined for most pre-industrial societies, whether the fishing and farming economies of Homeric Greece, or the raiding, mercenary and farming economies of the Norse, or the hunter- gatherer economies of Australia. Documenting a language is now seen as incomplete unless documenting place, story and song forms part of it. This book presents language documentation in its broadest sense in the Australian context, also giving a view of the documentation of Australian Aboriginal languages over time.1 In doing so, we celebrate the achievements of a pioneer in this field, Luise Hercus, who has documented languages, land, song and story in Australia over more than fifty years. -

The History of World Civilization. 3 Cyclus (1450-2070) New Time ("New Antiquity"), Capitalism ("New Slaveownership"), Upper Mental (Causal) Plan

The history of world civilization. 3 cyclus (1450-2070) New time ("new antiquity"), capitalism ("new slaveownership"), upper mental (causal) plan. 19. 1450-1700 -"neoarchaics". 20. 1700-1790 -"neoclassics". 21. 1790-1830 -"romanticism". 22. 1830-1870 – «liberalism». Modern time (lower intuitive plan) 23. 1870-1910 – «imperialism». 24. 1910-1950 – «militarism». 25.1950-1990 – «social-imperialism». 26.1990-2030 – «neoliberalism». 27. 2030-2070 – «neoromanticism». New history. We understand the new history generally in the same way as the representatives of Marxist history. It is a history of establishment of new social-economic formation – capitalism, which, in difference to the previous formations, uses the economic impelling and the big machine production. The most important classes are bourgeoisie and hired workers, in the last time the number of the employees in the sphere of service increases. The peasants decrease in number, the movement of peasants into towns takes place; the remaining peasants become the independent farmers, who are involved into the ware and money economy. In the political sphere it is an epoch of establishment of the republican system, which is profitable first of all for the bourgeoisie, with the time the political rights and liberties are extended for all the population. In the spiritual plan it is an epoch of the upper mental, or causal (later lower intuitive) plan, the humans discover the laws of development of the world and man, the traditional explanations of religion already do not suffice. The time of the swift development of technique (Satan was loosed out of his prison, according to Revelation 20.7), which causes finally the global ecological problems. -

Ken Macintyre and Barb Dobson 2017 Research Anthropologists

Ken Macintyre and Barb Dobson 2017 Research anthropologists www.anthropologyfromtheshed.com The writings of colonial recorders have often misrepresented Aboriginal people as deriving most of their food from the hunting of large game (kangaroo, wallaby, emu) when in fact the bulk of their diet (around 80%) was based on vegetable foods and small game, for example, lizards, goannas, snakes, insect larvae, rodents and small marsupials many of which are now endangered or extinct. Grub eating was looked down upon as an aberrant, opportunistic and almost degenerate means of human survival. This practice, like other unfamiliar food traditions such as indigenous geophagy (earth-eating) that we have described in a separate paper (www.anthropologyfromtheshed.com) only reinforced the colonial idea that the Aborigines of southwestern Australia, like those in other parts of Australia, were subhuman, uncivilized and deserved to be colonized by the economically, culturally and technologically superior ‘civilized’ white people. Little did the colonial superiors realize that traditional Nyungar knowledge of environmental, botanical, biological, phenological, ecological and entomological phenomena was heavily steeped in science and mythology and that this could have become a valuable asset to the colonizers had they wished to avail themselves of this knowledge. Nyungar people used a range of environmental and astronomical indicators for predicting weather, seasonality, animal breeding patterns, movements and so on. They understood how humans, animals, plants and all of life were interconnected and this awareness was manifest in their complicated web of kinship and totemistic affiliations, rituals and mythology. Even anthropology graduates often have great difficulty comprehending the intricacies of these classificatory totemic kin relationships that bonded humans to their natural world. -

Commonwealth of Australia

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 Warning This material has been reproduced and communicated to you by or on behalf of The Charles Darwin University with permission from the author(s). Any further reproduction or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander THESAURUS First edition by Heather Moorcroft and Alana Garwood 1996 Acknowledgements ATSILIRN conference delegates for the 1st and 2nd conferences. Alex Byrne, Melissa Jackson, Helen Flanders, Ronald Briggs, Julie Day, Angela Sloan, Cathy Frankland, Andrew Wilson, Loris Williams, Alan Barnes, Jeremy Hodes, Nancy Sailor, Sandra Henderson, Lenore Kennedy, Vera Dunn, Julia Trainor, Rob Curry, Martin Flynn, Dave Thomas, Geraldine Triffitt, Bill Perrett, Michael Christie, Robyn Williams, Sue Stanton, Terry Kessaris, Fay Corbett, Felicity Williams, Michael Cooke, Ely White, Ken Stagg, Pat Torres, Gloria Munkford, Marcia Langton, Joanna Sassoon, Michael Loos, Meryl Cracknell, Maggie Travers, Jacklyn Miller, Andrea McKey, Lynn Shirley, Xalid Abd-ul-Wahid, Pat Brady, Sau Foster, Barbara Lewancamp, Geoff Shepardson, Colleen Pyne, Giles Martin, Herbert Compton Preface Over the past months I have received many queries like "When will the thesaurus be available", or "When can I use it". Well here it is. At last the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Thesaurus, is ready. However, although this edition is ready, I foresee that there will be a need for another and another, because language is fluid and will change over time. As one of the compilers of the thesaurus I am glad it is finally completed and available for use. -

Department of the Environment Grants Report 2012-13

2012-2013 Grant Report Master List Program Title Program Component (if applicable) Recipient Purpose Value Approval Grant Term Grant Funding Location postcode Special confidentiality provisions – Notes (GST Incl) date (months) Y/N and reason (if yes) $ (00/00/00) Antarctic Science, Policy and Presence N/A University of New England Ecology and control methods: Managing the $80,300 24/01/13 36 Armidale NSW 2351 N/A invasive weed Poa annua in the Australian sub- Antarctic Antarctic Science, Policy and Presence N/A University of Newcastle The Role of Magnetospheric Plasma Waves in $145,717 30/01/13 48 Callaghan NSW 2308 N/A Driving Space Weather Antarctic Science, Policy and Presence N/A Australian National University Predicting change: Will morphological constraints $165,000 14/02/13 36 Canberra ACT 2600 N/A on hydraulic function limit acclimation of subantarctic plants to a warmer climate? Antarctic Science, Policy and Presence N/A Department of Primary Industries, Status and trends of Macquarie Island Albatrosses $73,350 27/02/13 48 Hobart TAS 7000 N/A Parks, Water and Environment and Giant Petrels: management and conservation of threatened seabirds Antarctic Science, Policy and Presence N/A University of Tasmania Sea ice microbial community dynamics in a $100,023 7/03/13 36 Sandy Bay TAS 7005 N/A changing climate Antarctic Science, Policy and Presence N/A University of Tasmania Conservation genetics of Antarctic seabirds and $99,440 7/03/13 48 Sandy Bay TAS 7005 N/A seals: population connectivity and past glacial refugia Antarctic Science, -

Australia Day

www.ESL HOLIDAY LESSONS.com AUSTRALIA DAY http://www.eslHolidayLessons.com/01/australia_day.html CONTENTS: The Reading / Tapescript 2 Phrase Match 3 Listening Gap Fill 4 Listening / Reading Gap Fill 5 Choose the Correct Word 6 Multiple Choice 7 Spelling 8 Put the Text Back Together 9 Scrambled Sentences 10 Discussion 11 Student Survey 12 Writing 13 Homework 14 ALL ANSWERS ARE IN THE TEXT ON PAGE 2. AUSTRALIA DAY THE READING / TAPESCRIPT Australia Day is celebrated annually on January the 26th. It is an official national holiday and most Australians take the day off work. All schools close. Australia Day commemorates the creation of the first British settlement in Australia in 1788. Captain Arthur Phillip, the very first Governor of New South Wales, set up a community to run a prison in what is now Sydney. The earliest records of Australia Day date back to 1808. Not all Australians celebrate this day. Many Aboriginal Australians do not like the idea of a day to celebrate the British landing. Aborigines have dubbed the 26 January as "Invasion Day" or "Survival Day". The latter name celebrates the fact that the Aboriginal peoples and culture have not been wiped out. The Prime Minister announces the Australian of the Year on the eve of Australia Day. This goes to the Australian who has made a "significant contribution to the Australian community and nation and is an inspirational role model for the Australian community". There are many other celebrations across the country, including many spectacular fireworks displays. The biggest one is in Perth, capital of Western Australia. -

The Vocabulary of Australian English

THE VOCABULARY OF AUSTRALIAN ENGLISH Bruce Moore Australian National Dictionary Centre Australian National University The vocabulary of Australian English comes from many sources. This document outlines some of the most important sources of Australian words, and some of the important historical events that have shaped the creation of Australian words. At times, reference is made to the Australian Oxford Dictionary (OUP 1999) edited by Bruce Moore. 1. BORROWINGS FROM AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL LANGUAGES ...2 2. ENGLISH FORMATIONS .....................................................................7 3. THE CONVICT ERA ...........................................................................11 4. BRITISH DIALECT .............................................................................15 5. BRITISH SLANG ................................................................................17 6. GOLD .................................................................................................18 7. WARS.................................................................................................21 © Australian National Dictionary Centre Page 1 of 24 1. BORROWINGS FROM AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL LANGUAGES In 1770 Captain James Cook was forced to beach the Endeavour for repairs near present-day Cooktown, after the ship had been damaged on reefs. He and Joseph Banks collected a number of Aboriginal words from the local Guugu Yimidhirr people. One of these words was kangaroo, the Guugu Yimidhirr name for the large black or grey kangaroo Macropus -

Consolidating and Enhancing Wirlomin Noongar Archival Material in the Community

Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 18 Archival returns: Central Australia and beyond ed. by Linda Barwick, Jennifer Green & Petronella Vaarzon-Morel, pp. 325–338 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/sp18 16 http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24890 Ever-widening circles: Consolidating and enhancing Wirlomin Noongar archival material in the community Clint Bracknell Edith Cowan University Kim Scott Curtin University Abstract Returning archival documentation of endangered Indigenous languages to their community of origin can provide empowering opportunities for Indigenous people to control, consolidate, enhance, and share their cultural heritage with ever-widening, concentric circles of people, while also allowing time and space for communities to recover from disempowerment and dislocation. This process aligns with an affirming narrative of Indigenous persistence that, despite the context of colonial dispossession, can lead to a positive, self-determined future. In 2007, senior Noongar of the Wirlomin clan in the south coast region of Western Australia initiated Wirlomin Noongar Language and Stories Inc., an organisation set up to facilitate cultural and linguistic revitalisation by combining community-held knowledge with documentation and recordings repatriated from the archives. Fieldnotes created in 1931 from discussions with local Aboriginal people at Albany, Western Australia have inspired the collaborative production of six illustrated bilingual books. Working with archival research material has presented challenges due -

Eucalyptus Oil Industry Introduction & History

Eucalyptus oil industry Introduction & history The eucalyptus oil story began in 1788 in Australia, when Surgeon-General John White, distilled oil from a eucalypt he called ‘Sydney Peppermint’. He sent the oil back to England where it was found to be ‘more efficacious in treating colic than English peppermint’. And with that the use of eucalyptus oil in medicinal products began. The antiseptic and healing properties were already known by aboriginal communities. In South Africa – started in 1950’s, when Marc Spraggen started producing eucalyptus oil on his farm Goede Hoop, in Mpumalanga. In the 1960’s, Richard Lunt, diversified his forestry operations and started Busby Essential Oils. Some of the many uses of Eucalyptus Oil INSECT BITES & STINGS AROMATHERAPY MASSAGE SORES, CUTS & ABRASIONS COLDS & FLU MUSCLE ACHES HEAD LICE Eucalyptus Oil Uses • Antifungal • Antispasmodic • Antibacterial • Decongestant • Antiviral • Expectorant • Anti-inflammatory • Healing - sores and wounds • Analgesic • Immuno-stimulant • Antioxidant • Relieves coughs, colds, flu • Antiseptic Different types of eucalyptus oil • 300 species and 700 varieties of eucalyptus trees • Quality & use depends on chemical constituents / fractions • Tea Tree Oil - Terpinen- 4-ol • Eucalyptus Oil – Cineol • Cineol (medicinal) oils • Globulus, Smithii, Radiata, Polybractea • Other oils • Citriodora & Dives Eucalyptus oil production • Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe, Russia, South America • China dominates world production: Metric Tons 12000 10000 8000 6000 MT 4000 2000 0 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 Industry Challenges • Quality requirements • Competitive market • Technical aspects: • Fractional distillation • Testing • Volumes Production in South Africa • Last 30 years – 5 major players • Challenges • Land • Labour • Water Use Licenses / drought • Timber Industry • Currency fluctuations CONCLUSION • Tough, challenging industry • However, we remain positive & continue to grow • By focusing on: • Quality, Systems, Accreditations & Customer Relationships Thank you for your time and interest in our industry. -

Than Three "Rs" in the Classroom" : a Case Study in Aboriginal Tertiary Business Education

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 2011 "More than three "Rs" in the classroom" : a case study in Aboriginal tertiary business education Keith Truscott Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses Part of the Business Commons, and the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Truscott, K. (2011). "More than three "Rs" in the classroom" : a case study in Aboriginal tertiary business education. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/925 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/925 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form.