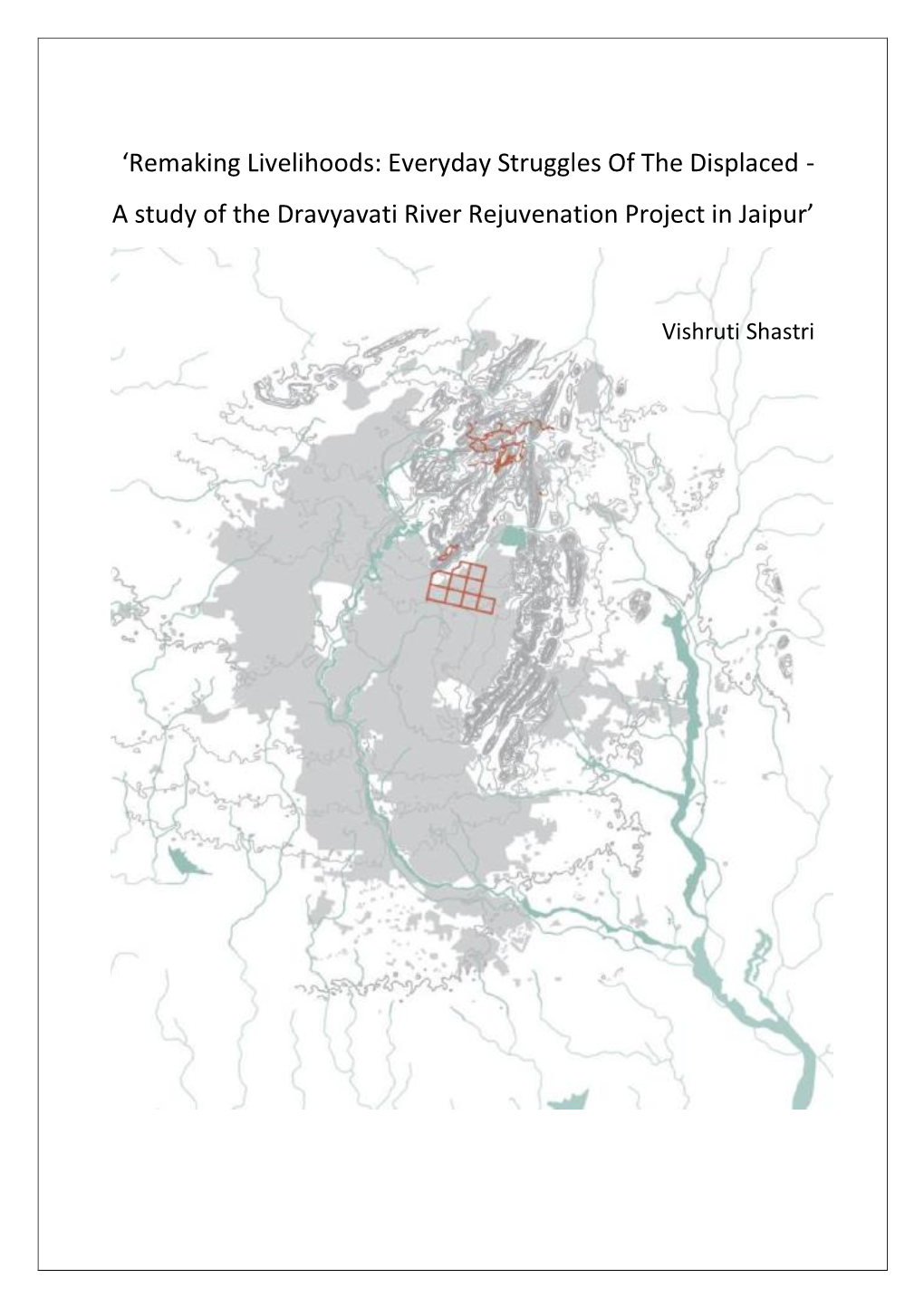

Remaking Livelihoods: Everyday Struggles of the Displaced - a Study of the Dravyavati River Rejuvenation Project in Jaipur’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Water Insecurity and Sanitation in Asia

WATER INSECURITY AND SANITATION IN ASIA Edited by Naoyuki Yoshino, Eduardo Araral, and KE Seetha Ram ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK INSTITUTE PANTONE 281C WATER INSECURITY AND SANITATION IN ASIA Edited by Naoyuki Yoshino, Eduardo Araral, and KE Seetha Ram © 2019 Asian Development Bank Institute All rights reserved. First printed in 2019. ISBN 978–4–89974–113–8 (Print) ISBN 978–4–89974–114-5 (PDF) The views in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI), its Advisory Council, ADB’s Board or Governors, or the governments of ADB members. ADBI does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. ADBI uses proper ADB member names and abbreviations throughout and any variation or inaccuracy, including in citations and references, should be read as referring to the correct name. By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or by using the term “recognize,” “country,” or other geographical names in this publication, ADBI does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Users are restricted from reselling, redistributing, or creating derivative works without the express, written consent of ADBI. The Asian Development Bank recognizes “China” as the People’s Republic of China, "Korea" as the Republic of Korea, and "Vietnam" as Viet Nam. Note: In this publication, “$” refers to US dollars. Asian Development Bank Institute -

IDL-56493.Pdf

Changes, Continuities, Contestations:Tracing the contours of the Kamathipura's precarious durability through livelihood practices and redevelopment efforts People, Places and Infrastructure: Countering urban violence and promoting justice in Mumbai, Rio, and Durban Ratoola Kundu Shivani Satija Maps: Nisha Kundar March 25, 2016 Centre for Urban Policy and Governance School of Habitat Studies Tata Institute of Social Sciences This work was carried out with financial support from the UK Government's Department for International Development and the International Development Research Centre, Canada. The opinions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect those of DFID or IDRC. iv Acknowledgments We are grateful for the support and guidance of many people and the resources of different institutions, and in particular our respondents from the field, whose patience, encouragement and valuable insights were critical to our case study, both at the level of the research as well as analysis. Ms. Preeti Patkar and Mr. Prakash Reddy offered important information on the local and political history of Kamathipura that was critical in understanding the context of our site. Their deep knowledge of the neighbourhood and the rest of the city helped locate Kamathipura. We appreciate their insights of Mr. Sanjay Kadam, a long term resident of Siddharth Nagar, who provided rich history of the livelihoods and use of space, as well as the local political history of the neighbourhood. Ms. Nirmala Thakur, who has been working on building awareness among sex workers around sexual health and empowerment for over 15 years played a pivotal role in the research by facilitating entry inside brothels and arranging meetings with sex workers, managers and madams. -

A Report on Trafficking in Women and Children in India 2002-2003

NHRC - UNIFEM - ISS Project A Report on Trafficking in Women and Children in India 2002-2003 Coordinator Sankar Sen Principal Investigator - Researcher P.M. Nair IPS Volume I Institute of Social Sciences National Human Rights Commission UNIFEM New Delhi New Delhi New Delhi Final Report of Action Research on Trafficking in Women and Children VOLUME – 1 Sl. No. Title Page Reference i. Contents i ii. Foreword (by Hon’ble Justice Dr. A.S. Anand, Chairperson, NHRC) iii-iv iii. Foreword (by Hon’ble Mrs. Justice Sujata V. Manohar) v-vi iv. Foreword (by Ms. Chandani Joshi (Regional Programme Director, vii-viii UNIFEM (SARO) ) v. Preface (by Dr. George Mathew, ISS) ix-x vi. Acknowledgements (by Mr. Sankar Sen, ISS) xi-xii vii. From the Researcher’s Desk (by Mr. P.M. Nair, NHRC Nodal Officer) xii-xiv Chapter Title Page No. Reference 1. Introduction 1-6 2. Review of Literature 7-32 3. Methodology 33-39 4. Profile of the study area 40-80 5. Survivors (Rescued from CSE) 81-98 6. Victims in CSE 99-113 7. Clientele 114-121 8. Brothel owners 122-138 9. Traffickers 139-158 10. Rescued children trafficked for labour and other exploitation 159-170 11. Migration and trafficking 171-185 12. Tourism and trafficking 186-193 13. Culturally sanctioned practices and trafficking 194-202 14. Missing persons versus trafficking 203-217 15. Mind of the Survivor: Psychosocial impacts and interventions for the survivor of trafficking 218-231 16. The Legal Framework 232-246 17. The Status of Law-Enforcement 247-263 18. The Response of Police Officials 264-281 19. -

Sustainable Social Housing in India

Sustainable Social Housing in India Definition, Challenges and Opportunities Technical Report Gregor Herda, Sonia Rani, Pratibha Ruth Caleb, Rajat Gupta, Megha Behal, Matt Gregg, Srijani Hazra May 2017 MaS-SHIP Mainstreaming Sustainable Social Housing in India Project i | P a g e MaS-SHIP (Mainstreaming Sustainable Social Housing in India project) is an initiative by the Low- Carbon Building Group at Oxford Brookes University, The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI), Development Alternatives and UN-Habitat, that seeks to promote sustainability in terms of environmental performance, affordability and social inclusion as an integrated part of social housing in India. MaS-SHIP is supported by the Sustainable Buildings and Construction Programme of the 10- Year Framework of Programmes on Sustainable Consumption and Production (10-YFP). This report should be referenced as: Herda, G., Rani, S., Caleb, P. R., Gupta, R., Behal, M., Gregg, M. and Hazra, S. (2017). Sustainable social housing in India: definition, challenges and opportunities - Technical Report, Oxford Brookes University, Development Alternatives, The Energy and Resources Institute and UN-Habitat. Oxford. ISBN: 978-0-9929299-8 Technical peer reviewers: Professor Amita Bhide, Tata Institute of Social Sciences Dr Sameer Maithel, Greentech Knowledge Solutions Professor B V Venkatarama Reddy, Indian Institute of Science For more information on the MaS-SHIP project, please visit; www.mainstreamingsustainablehousing.org Or contact Professor Rajat Gupta: [email protected] Published by: Low Carbon Building Group, Oxford Institute for Sustainable Development, Oxford Brookes University © Oxford Brookes University, Development Alternatives, The Energy and Resources Institute and UN-Habitat, 2017 Images front and back cover: MaS-SHIP team The MaS-SHIP research team wishes to encourage access to, and circulation of, its work as widely as possible without affecting the ownership of the copyright, which remains with the copyright holder. -

Delhi's Slum-Dwellers

Working paper Delhi’s Slum- Dwellers Deprivation, Preferences and Political Engagement among the Urban Poor Abhijit Banerjee Rohini Pande Michael Walton October 2012 -PRELIMINARY- 1 Delhi’s Slum-Dwellers: Deprivation, Preferences and Political Engagement among the Urban Poor Abhijit Banerjee, Rohini Pande and Michael Walton October 22, 2012 I. Introduction. Today, India is one of the world’s fastest growing economies and, increasingly, an industrial and service-oriented economy.1 Reflecting this, between 2001 and 2008 India’s urban population increased from 290 million to 340 million. Yet, India remains under-urbanized relative to her income level, leading to widespread expectations of large-scale rural-to-urban migration in coming years (McKinsey Global Institute 2010). Some estimates suggest that the urban population may be close to 600 million by 2030 (High Powered Expert Committee 2011). Many countries have stumbled in the transition from lower-middle income to higher-middle income status, experiencing growth slowdowns as they failed to effect the institutional and infrastructural changes necessary to support this shift. In the case of India, it is likely that the critical changes will be in the governance of urban areas and the provision of services to the growing numbers of migrants settling in urban slums. This paper uses detailed survey data on the quality of social services available to Delhi slum-dwellers to highlight the governance constraints currently faced by low- income households in a large Indian city and to provide evidence on some of the contributing factors. Delhi is India’s second largest metropolis, with a population of around 18 million (High Powered Expert Committee 2011). -

City Profile Poverty, Inequality and Violence in Urban India

Safe and Inclusive Cities Delhi: City Profile Neelima Risbud Poverty, Inequality and Violence in Urban India: Towards Inclusive Planning and Policies Institute for Human Development 2016 3rd Floor, NIDM Building, IIPA Campus M.G Road, New Delhi-110002 Tel: 011-23358166, 011-23321610. Fax: 011-23765410 Email: [email protected]/web: www.ihdindia.org 1 2 CITY PROFILE: DELHI Contents Abstract Acknowledgments Introduction 1. Context of Historic development ...................................................................... 1 2. The NCR and the CNCR Regional context ..................................................... 3 3. The City Profile ................................................................................................ 5 3.1 Demography ............................................................................................... 9 3.2 Education and Health ................................................................................ 10 3.3 Economy, Employment and Poverty in Delhi ............................................ 11 4. Urban Development initiatives .................................................................... 17 4.1 Master Plan policies and Land Policies...................................................................17 4.2 Spatial Segmentation................................................................................ 20 4.3 Housing Scenario .................................................................................... 23 4.4 Designated Slums ................................................................................... -

Conversations Dance Studies

CONVERSATIONS ACROSS THE FIELD OF DANCE STUDIES Decolonizing Dance Discourses Dance Studies Association 2020 | Volume XL CONVERSATIONS ACROSS THE FIELD OF DANCE STUDIES Decolonizing Dance Discourses Dance Studies Association 2020 | Volume XL Table of Contents Preface | 2019 GATHERINGS Anurima Banerji and Royona Mitra: Guest Co-Editors ���������������������� 4 Introductory Remarks | OPENING WORDS Anurima Banerji and Royona Mitra ������������������������������������������������� 22 Takiyah Nur Amin������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 6 On Dance Black Women Respond to a Double Pandemic: Black Laws of Dance | "The Emotional W(ait)eight" | Jasmine Johnson����������������������������������������������������������������������������� 25 Crystal U� Davis and Nyama McCarthy-Brown�������������������������������� 10 The Problem with "Dance" | The Politics of Naming the South Indian Dancer | Prarthana Purkayastha �������������������������������������������������������������������� 28 Nrithya Pillai������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 13 RUXIMIK QAK’U’X: Inextricable Relationalities It is Time for a Caste Reckoning in Indian in Mayan Performance Practice | "Classical" Dance | Maria Firmino-Castillo....................................................................... 31 Anusha Kedhar �������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 16 On Choreography Discussing the Undiscussable, Part 2; Decentering Choreography: Natya as Postcolonial -

Vkocl" the Politics and Anti-Politics of Shelter Policy in Chennai, India

The Politics and Anti-Politics of Shelter Policy in Chennai, India By MASSACHUS-TS INSi E OF TECHNOLOGY Nithya V. Raman SEP 059 2008 A.B. Social Studies Harvard University, 2002 LIBRARIES SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF URBAN STUDIES AND PLANNING IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER IN CITY PLANNING AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SEPTEMBER 2008 C 2008 Nithya V. Raman. All Rights Reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT the permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of the thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Author Department of trban Studies and Planning - cAugust 12, 2008) Certified by Prof4 ssor Balakrishnan Rajagopal Department of Urban Studies and Planning Thesis Supervisor Accepted by Professor Souza Briggs C [ir, MCP Committee Department of Urbanr tudies and Planning vkocl" The Politics and Anti-Politics of Shelter Policy in Chennai, India By Nithya V. Raman Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on August 18, 2008 In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master in City Planning ABSTRACT Many scholars argue that global forces, such as increased economic integration into the global economy or interventions from international aid agencies, are directly affecting the governance of municipalities. This paper explores the process by which international influences affect local governance by using the history of a single institution, the Tamil Nadu Slum Clearance Board in Chennai, India, and examining the evolution of the Board's policies towards slums and slum clearance from 1970 to the present. -

Month of February-2019

CURRENT AFFAIRS MONTH OF FEBRUARY-2019 Plot-1441, Opp. IOCL Petrol Pump, CRP Square, Bhubaneswar Ph : 8093083555, 8984111101 Web : www.vanikias.com | E-mail : [email protected] www.facebook.com/vanikias CURRENT AFFAIRS – FEBRUARY–2019 Source-PIB 01.02.2019 A unique travelogue series ‘Rag Rag Mein Ganga’ launched on Doordarshan Union Minister for Water Resources, 1. Budget Highlights 2019-20 River Development and Ganga Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi Rejuvenation launched travelogue (PM-KISAN) program “Rag Rag Mein Ganga” on To extend direct income support at the Doordarshan. rate of Rs. 6,000 per year to farmer This series has been made by families, having cultivable land upto Doordarshan in collaboration with 2 hectares. National Mission for Clean Ganga Under this Government of India funded (NMCG). Scheme, Rs.2,000 each will be The show relays the message of the transferred to the bank accounts of need of rejuvenating River Ganga around 12 crore Small and Marginal while also informing about the efforts farmer families, in three equal of the Government to clean Ganga – instalments. presented in a unique and interesting This programme would be made effective format. from 1st December 2018 and the first Topic- GS Paper 1 –Art and Culture instalment for the period upto31st Source-PIB March 2019 would be paid. DIPP renamed as DPIIT The government has notified changing the name of the Department of Pradhan Mantri Shram-Yogi Maandhan Industrial Policy & Promotion (DIPP) to Under the scheme, an assured the Department for Promotion of monthly pension of Rs 3,000 per Industry and Internal Trade (DPIIT). -

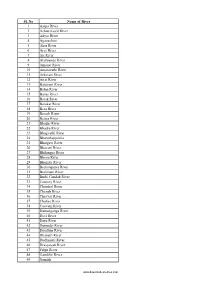

List of Rivers in India

Sl. No Name of River 1 Aarpa River 2 Achan Kovil River 3 Adyar River 4 Aganashini 5 Ahar River 6 Ajay River 7 Aji River 8 Alaknanda River 9 Amanat River 10 Amaravathi River 11 Arkavati River 12 Atrai River 13 Baitarani River 14 Balan River 15 Banas River 16 Barak River 17 Barakar River 18 Beas River 19 Berach River 20 Betwa River 21 Bhadar River 22 Bhadra River 23 Bhagirathi River 24 Bharathappuzha 25 Bhargavi River 26 Bhavani River 27 Bhilangna River 28 Bhima River 29 Bhugdoi River 30 Brahmaputra River 31 Brahmani River 32 Burhi Gandak River 33 Cauvery River 34 Chambal River 35 Chenab River 36 Cheyyar River 37 Chaliya River 38 Coovum River 39 Damanganga River 40 Devi River 41 Daya River 42 Damodar River 43 Doodhna River 44 Dhansiri River 45 Dudhimati River 46 Dravyavati River 47 Falgu River 48 Gambhir River 49 Gandak www.downloadexcelfiles.com 50 Ganges River 51 Ganges River 52 Gayathripuzha 53 Ghaggar River 54 Ghaghara River 55 Ghataprabha 56 Girija River 57 Girna River 58 Godavari River 59 Gomti River 60 Gunjavni River 61 Halali River 62 Hoogli River 63 Hindon River 64 gursuti river 65 IB River 66 Indus River 67 Indravati River 68 Indrayani River 69 Jaldhaka 70 Jhelum River 71 Jayamangali River 72 Jambhira River 73 Kabini River 74 Kadalundi River 75 Kaagini River 76 Kali River- Gujarat 77 Kali River- Karnataka 78 Kali River- Uttarakhand 79 Kali River- Uttar Pradesh 80 Kali Sindh River 81 Kaliasote River 82 Karmanasha 83 Karban River 84 Kallada River 85 Kallayi River 86 Kalpathipuzha 87 Kameng River 88 Kanhan River 89 Kamla River 90 -

Downloads/Docs/4625 51419 GC%2021%20What%20Are%20Slums.Pdf

Acknowledgement The Centre for Global Development Research (CGDR) is extremely thankful to the Socio‐Economic Research Davison of the Planning Commission, Government of India for assigning this important and prestigious study. We also thankful to officials of Planning Commission including Members, Adviser (HUD), Adviser (SER), Deputy Secretary (SER), and Senior Research Officer (SER) for their interest in the study and necessary guidance at various stages of the study. We are also extremely thankful to those who have helped in facilitating the survey and providing information. In this context we wish to thank the Chief Minister of Delhi; local leaders including Members of Parliament; Members of Legislative Assembly of Delhi; Councillors of Municipal Corporation of Delhi and New Delhi Municipal Corporation; Pradhans and community leaders of slums across Delhi. Special thanks are due to the officials of JJ slum wing, MCD, Punarwas Bhawan, New Delhi; officials of Sewer Department of MCD; various news reporters and Social workers for their contribution and help in completing the research. We are also highly thankful to officials of numerous non‐government organisations for their cooperation with the CGDR team during the course of field work. We acknowledge with gratitude the intellectual advice from Professor K.P. Kalirajan on various issues related to the study. Thanks are also due to Mr. S. K. Mondal for his contribution in preparation of this report. We are also thankful to Ms Mridusmita_Bordoloi for her contribution in preparing case studies. This report is an outcome of tireless effort made by the staff of CGDR led by Mr. Indrajeet Singh. We wish to specially thank the entire CGDR team. -

Economics Theses in Harvard Archives

Economics Theses in Harvard Archives Department of Economics *Hoopes Winners Rev. June 2021 2021 THESES IN HARVARD ARCHIVES Manuel Abecasis External Imbalances and the Neutral Rate of Interest Larry Summers Ryan Bayer Teaching with Technology: Understanding the Relationship Between Chiara Farronato Educational Outcomes and Internet Access through E-Rate Subsidy Jonah Berger Differential School Discipline In Times of Economic Stress: Evidence Lawrence Katz from the Great Recession Joel Byman Is God Online? Estimating the Impact of the Internet on American Robert Barro Religion Jennifer Chen* Media Representation and Racial Prejudice: Evidence from The Amos Desmond Ang ‘n’ Andy Show Langston Chen Cooperation or Coercion? Examining the Political and Trade Impacts of Emily Breza Chinese Financial Flows to Africa Matty Cheng Incremental Innovation: An Analysis of Developer Responsiveness on Andy Wu Mobile Apps Wesley Donhauser Morality and Family: Demand as a Function of Moral Attitude Claudia Goldin Peyton Dunham The Long-Term Effects of Redlining on Environmental Health Nathan Nunn Sophie Edouard Do Judges Violate the 8th Amendment When Setting Bail? Evidence Chris Foote from Jail Roster Data Oliver Erle A Wave of Destruction and New Ideas: Investigating the Impacts of Josh Lerner Natural Disasters on Innovation in China Zach Fraley Estate Economics: The 20th Century Decline of the English Estate Hans Helmut Kotz Zoe Gompers Somewhere to Go: Latrine Construction, Access, and Women and Gautam Rao Children’s Well-Being in India Alexander Green