Housinglandrightsnetwork.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

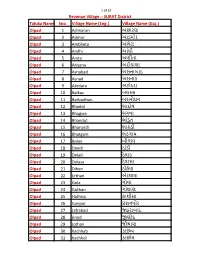

Taluka Name Sno. Village Name (Eng.) Village Name (Guj.) Olpad 1

1 of 32 Revenue Village :: SURAT District Taluka Name Sno. Village Name (Eng.) Village Name (Guj.) Olpad 1 Achharan અછારણ Olpad 2 Admor આડમોર Olpad 3 Ambheta અંભેટા Olpad 4 Andhi આંઘી Olpad 5 Anita અણીતા Olpad 6 Ariyana અરીયાણા Olpad 7 Asnabad અસનાબાદ Olpad 8 Asnad અસનાડ Olpad 9 Atodara અટોદરા Olpad 10 Balkas બલકસ Olpad 11 Barbodhan બરબોઘન Olpad 12 Bhadol ભાદોલ Olpad 13 Bhagwa ભગવા Olpad 14 Bhandut ભાંડુત Olpad 15 Bharundi ભારં ડી Olpad 16 Bhatgam ભટગામ Olpad 17 Bolav બોલાવ Olpad 18 Dandi દાંડી Olpad 19 Delad દેલાડ Olpad 20 Delasa દેલાસા Olpad 21 Dihen દીહેણ Olpad 22 Erthan એરથાણ Olpad 23 Gola ગોલા Olpad 24 Gothan ગોથાણ Olpad 25 Hathisa હાથીસા Olpad 26 Isanpor ઇશનપોર Olpad 27 Jafrabad જાફરાબાદ Olpad 28 Jinod જીણોદ Olpad 29 Jothan જોથાણ Olpad 30 Kachhab કાછબ Olpad 31 Kachhol કાછોલ 2 of 32 Revenue Village :: SURAT District Taluka Name Sno. Village Name (Eng.) Village Name (Guj.) Olpad 32 Kadrama કદરામા Olpad 33 Kamroli કમરોલી Olpad 34 Kanad કનાદ Olpad 35 Kanbhi કણભી Olpad 36 Kanthraj કંથરાજ Olpad 37 Kanyasi કન્યાસી Olpad 38 Kapasi કપાસી Olpad 39 Karamla કરમલા Olpad 40 Karanj કરંજ Olpad 41 Kareli કારલે ી Olpad 42 Kasad કસાદ Olpad 43 Kasla Bujrang કાસલા બજુ ઼ રંગ Olpad 44 Kathodara કઠોદરા Olpad 45 Khalipor ખલીપોર Olpad 46 Kim Kathodra કીમ કઠોદરા Olpad 47 Kimamli કીમામલી Olpad 48 Koba કોબા Olpad 49 Kosam કોસમ Olpad 50 Kslakhurd કાસલાખુદદ Olpad 51 Kudsad કુડસદ Olpad 52 Kumbhari કુભારી Olpad 53 Kundiyana કુદીયાણા Olpad 54 Kunkni કુંકણી Olpad 55 Kuvad કુવાદ Olpad 56 Lavachha લવાછા Olpad 57 Madhar માધ઼ ર Olpad 58 Mandkol મંડકોલ Olpad 59 Mandroi મંદરોઇ Olpad 60 Masma માસમા Olpad 61 Mindhi મીઢં ીં Olpad 62 Mirjapor મીરઝાપોર 3 of 32 Revenue Village :: SURAT District Taluka Name Sno. -

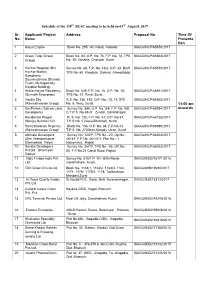

Schedule of the 338Th SEAC Meeting to Be Held on 03Rd Augestl, 2017 Sr. No. Applicant/ Project Name Address Proposal No Time Of

Schedule of the 338th SEAC meeting to be held on 03rd Augestl, 2017 Sr. Applicant/ Project Address Proposal No Time Of No. Name Presenta tion 1 Aarya Empire Block No. 255, Vill. Kalali, Vadodar SIA/GJ/NCP/65870/2017 2 Green Tulip (Green Block No. 83, O.P. No. 78, F.P. No. 78, TPS SIA/GJ/NCP/65903/2017 Group) No. 30, Vanakla, Choryasi, Surat. 3 Harihar Hospital, Shri Survey No. 68, F.P. No. 43/2, O.P. 43, Draft SIA/GJ/NCP/65910/2017 Harihar Maharj TPS No. 60, Khodiyar, Daskroi, Ahmedabad Kamdhenu Dausevashram Dharmik Trust ( Multispecialty Hospital Building) 4 Ashtavinayak Residency Block No. 649, F.P. No. 18, O.P. No. 18, SIA/GJ/NCP/65911/2017 (Sumukh Enterprise) TPS No. 12 ,Puna, Surat. 5 Vanilla Sky R.S. No. 136, 143, O.P. No.; 15, 16 TPS SIA/GJ/NCP/65925/2017 (Rameshwaram Group) No. 5, Vesu, Surat. 11:00 am 6 DevParam ( Soham Land Survey No. 384, O.P. No.159, F.P. No.159, SIA/GJ/NCP/65934/2017 onwards Developers) D.T.P.S. No-69 At Zundal, Gandhinagar, 7 Residential Project R. S. No: 132, F.P. No: 57, O.P. No 57, SIA/GJ/NCP/64135/2017 (Sanjay Surana Huf) T.P.S No: 5 (Vesu-Bhimrad), Surat 8 Rameshwaram Regency Block No. 136, O.P. No. 38, F.P.No.41, SIA/GJ/NCP/65980/2017 (Rameshwaram Group) T.P.S. No. 27(Utran-Kosad), Utran, Surat 9 Ultimate Developers Survey No: 120/P, TPS No.:-20, Op.No.- SIA/GJ/NCP/66003/2017 (Shri Virendrakumar 46+47, F.P.No.-46+47/1, Plot No.:- 1, Manharbhai Patel) Nanamava, Rajkot 10 Savalia Developers Survey No: 267/P, TPS No.:-06, OP.No.- SIA/GJ/NCP/66023/2017 Pvt.Ltd Dharmesh 05, F.P.No.21 Canal Road, Rajkot. -

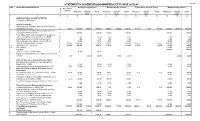

Statement V : Scheme Wise Budget

STATEMENT:V SCHEME/PROGRAMME/PROJECTS WISE OUTLAY ₹ in Lakh S.No. Sector/Department/Scheme Budget Outlay 2019-20 Revised Outlay 2019-20 Expenditure 2019-20 (Prov.) Budget Outlay 2020-21 R Expenditure C 2018-19 Revenue Capital/ Total Revenue Capital/ Total Revenue Capital/ Total Revenue Capital/ Total L Loan Loan Loan Loan 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 AGRICULTURE & ALLIED ACTIVITIES A Development Department I Animal Husbandry 1 Improvement of Veterinary Services and Control of Contagious Diseases C 170.65 800.00 700.00 1500.00 800.00 700.00 1500.00 519.94 28.99 548.93 1300.00 3000.00 4300.00 2 Improvement of Veterinary Services and Control of Contagious Diseases-SCSP R 100.00 100.00 100.00 100.00 100.00 100.00 3 Farm Advisiory Integrated agricultural development scheme including extn. , education etc. -SCSP R 5.00 5.00 5.00 5.00 4.00 4.00 4 Soil testing & Soil reclamation & saline-SCSP R 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 1.00 5 GIA to animal welfare advisory board of Delhi R 10.00 10.00 10.00 10.00 80.00 80.00 6 GIA for Shifting of Dairy Colonies R 1060.82 1200.00 1200.00 1200.00 1200.00 1167.34 1167.34 1200.00 1200.00 7.a GIA to S.P.C.A. (General) R 289.00 400.00 400.00 210.00 210.00 210.00 210.00 80.00 80.00 7.b GIA (Salary) R 220.00 220.00 Sub total 300.00 300.00 8 Input sale Centres at BDO Offices R 30.00 30.00 9 Expansion & Reorganisation of fishery activities in UT of Delhi C 4.63 20.00 20.00 17.00 17.00 20.00 20.00 2 National Mission on Sustainable Agriculture a. -

Yojana and Kurukshetra- September 2017

Yojana and Kurukshetra- September 2017 www.iasbaba.com Page | 1 Yojana and Kurukshetra- September 2017 Preface This is our 30th edition of Yojana Gist and 21st edition of Kurukshetra Gist, released for the month of September, 2017. It is increasingly finding a place in the questions of both UPSC Prelims and Mains and therefore, we’ve come up with this initiative to equip you with knowledge that’ll help you in your preparation for the CSE. Every Issue deals with a single topic comprehensively sharing views from a wide spectrum ranging from academicians to policy makers to scholars. The magazine is essential to build an in-depth understanding of various socio-economic issues. From the exam point of view, however, not all articles are important. Some go into scholarly depths and others discuss agendas that are not relevant for your preparation. Added to this is the difficulty of going through a large volume of information, facts and analysis to finally extract their essence that may be useful for the exam. We are not discouraging from reading the magazine itself. So, do not take this as a document which you take read, remember and reproduce in the examination. Its only purpose is to equip you with the right understanding. But, if you do not have enough time to go through the magazines, you can rely on the content provided here for it sums up the most essential points from all the articles. You need not put hours and hours in reading and making its notes in pages. We believe, a smart study, rather than hard study, can improve your preparation levels. -

Government Cvcs for Covid Vaccination for 18 Years+ Population

S.No. District Name CVC Name 1 Central Delhi Anglo Arabic SeniorAjmeri Gate 2 Central Delhi Aruna Asaf Ali Hospital DH 3 Central Delhi Balak Ram Hospital 4 Central Delhi Burari Hospital 5 Central Delhi CGHS CG Road PHC 6 Central Delhi CGHS Dev Nagar PHC 7 Central Delhi CGHS Dispensary Minto Road PHC 8 Central Delhi CGHS Dispensary Subzi Mandi 9 Central Delhi CGHS Paharganj PHC 10 Central Delhi CGHS Pusa Road PHC 11 Central Delhi Dr. N.C. Joshi Hospital 12 Central Delhi ESI Chuna Mandi Paharganj PHC 13 Central Delhi ESI Dispensary Shastri Nagar 14 Central Delhi G.B.Pant Hospital DH 15 Central Delhi GBSSS KAMLA MARKET 16 Central Delhi GBSSS Ramjas Lane Karol Bagh 17 Central Delhi GBSSS SHAKTI NAGAR 18 Central Delhi GGSS DEPUTY GANJ 19 Central Delhi Girdhari Lal 20 Central Delhi GSBV BURARI 21 Central Delhi Hindu Rao Hosl DH 22 Central Delhi Kasturba Hospital DH 23 Central Delhi Lady Reading Health School PHC 24 Central Delhi Lala Duli Chand Polyclinic 25 Central Delhi LNJP Hospital DH 26 Central Delhi MAIDS 27 Central Delhi MAMC 28 Central Delhi MCD PRI. SCHOOl TRUKMAAN GATE 29 Central Delhi MCD SCHOOL ARUNA NAGAR 30 Central Delhi MCW Bagh Kare Khan PHC 31 Central Delhi MCW Burari PHC 32 Central Delhi MCW Ghanta Ghar PHC 33 Central Delhi MCW Kanchan Puri PHC 34 Central Delhi MCW Nabi Karim PHC 35 Central Delhi MCW Old Rajinder Nagar PHC 36 Central Delhi MH Kamla Nehru CHC 37 Central Delhi MH Shakti Nagar CHC 38 Central Delhi NIGAM PRATIBHA V KAMLA NAGAR 39 Central Delhi Polyclinic Timarpur PHC 40 Central Delhi S.S Jain KP Chandani Chowk 41 Central Delhi S.S.V Burari Polyclinic 42 Central Delhi SalwanSr Sec Sch. -

IDL-56493.Pdf

Changes, Continuities, Contestations:Tracing the contours of the Kamathipura's precarious durability through livelihood practices and redevelopment efforts People, Places and Infrastructure: Countering urban violence and promoting justice in Mumbai, Rio, and Durban Ratoola Kundu Shivani Satija Maps: Nisha Kundar March 25, 2016 Centre for Urban Policy and Governance School of Habitat Studies Tata Institute of Social Sciences This work was carried out with financial support from the UK Government's Department for International Development and the International Development Research Centre, Canada. The opinions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect those of DFID or IDRC. iv Acknowledgments We are grateful for the support and guidance of many people and the resources of different institutions, and in particular our respondents from the field, whose patience, encouragement and valuable insights were critical to our case study, both at the level of the research as well as analysis. Ms. Preeti Patkar and Mr. Prakash Reddy offered important information on the local and political history of Kamathipura that was critical in understanding the context of our site. Their deep knowledge of the neighbourhood and the rest of the city helped locate Kamathipura. We appreciate their insights of Mr. Sanjay Kadam, a long term resident of Siddharth Nagar, who provided rich history of the livelihoods and use of space, as well as the local political history of the neighbourhood. Ms. Nirmala Thakur, who has been working on building awareness among sex workers around sexual health and empowerment for over 15 years played a pivotal role in the research by facilitating entry inside brothels and arranging meetings with sex workers, managers and madams. -

Journal16-2.Pdf

Institute of Town Planners, India Journal 16 x 2, April - June 2019 ISSN : 0537 - 9679 Editorial This issue contains six papers. The first paper is on “Affordable Housing Provision in the Context of Kolkata Metropolitan Area’’, and is authored by Joy Karmakar who highlights Government of India’s mission of affordable housing for all citizens by 2022. He argues that the mission has become a major talking point for the people including policy makers to private developers to scholars at different levels. The idea of affordability and affordable housing has been defined by various organizations over the years but no unanimous definition has emerged. The need for affordable housing in the urban area is not new to India and especially mega cities like Kolkata. The paper revisits and assesses the affordable housing provision in Kolkata Metropolitan Area and how the idea of affordable housing provision has evolved over the years. It becomes clear from the analysis that the role of the state in providing affordable housing to urban poor has not only been reduced but shifted to the middle class. The second paper titled “Property Tax: Role of Technology in Process Improvement, Transparency and Revenue Enhancement’’ is written by Dinesh Ahlawat, Saurav Sen and Akshat Jain, discusses property tax reforms with a focus on current assessment, collection and record keeping of property tax data in the ULBs and how these issues can be resolved with the adoption of streamlined processes and use of technology. The author explains that property tax is evaluated differently for different properties. Presently, the traditional methods for tax assessment are causing delays in the process, a large number of unassessed properties remain, and several properties are not assessed correctly due to dependency on manual efforts. -

National Parks in India (State Wise)

National Parks in India (State Wise) Andaman and Nicobar Islands Rani Jhansi Marine National Park Campbell Bay National Park Galathea National Park Middle Button Island National Park Mount Harriet National Park South Button Island National Park Mahatma Gandhi Marine National Park North Button Island National ParkSaddle Peak National Park Andhra Pradesh Papikonda National Park Sri Venkateswara National Park Arunachal Pradesh Mouling National Park Namdapha National Park Assam Dibru-Saikhowa National Park Orang National Park Manas National Park (UNESCO World Heritage Centre) Nameri National Park Kaziranga National Park (Famous for Indian Rhinoceros, UNESCO World Heritage Centre) Bihar Valmiki National Park Chhattisgarh Kanger Ghati National Park Guru Ghasidas (Sanjay) National Park Indravati National Park Goa Mollem National Park Gujarat Marine National Park, Gulf of Kutch Vansda National Park Blackbuck National Park, Velavadar Gir Forest National Park Haryana WWW.BANKINGSHORTCUTS.COM WWW.FACEBOOK.COM/BANKINGSHORTCUTS 1 National Parks in India (State Wise) Kalesar National Park Sultanpur National Park Himachal Pradesh Inderkilla National Park Khirganga National Park Simbalbara National Park Pin Valley National Park Great Himalayan National Park Jammu and Kashmir Salim Ali National Park Dachigam National Park Hemis National Park Kishtwar National Park Jharkhand Hazaribagh National Park Karnataka Rajiv Gandhi (Rameswaram) National Park Nagarhole National Park Kudremukh National Park Bannerghatta National Park (Bannerghatta Biological Park) -

Final ELIGIBILITY Male 11-12

DIRECTORATE OF EDUCATION (ESTT.-II BRANCH) FINAL ELIGIBILITY LIST FOR PROMOTION TO THE POST OF LECTURER (AGRICULTURE) MALE 2011-12 S.No. Employee Employee Name Date of Birth School ID School Name Present Post SENIORITY BLOCK Date of Date of REMARKS ID NO. YEAR appointment acquiring to the post of Qualification TGT for the post of Lecturer UR NO CANDIDATE SC 1 20051829 RAJENDRA PRASAD 01-May-64 1106119 GBSSS A-BLK, NAND TGT S.ST. 9672 2003-09 31-Oct-92 1988 NAGRI ST NO CANDIDATE Page 1 of 249 DIRECTORATE OF EDUCATION (ESTT.-II BRANCH) FINAL ELIGIBILITY LIST FOR PROMOTION TO THE POST OF LECTURER (BIOLOGY) MALE 2011-12 S.No. Employee Employee Name Date of Birth School ID School Name Present Post SENIORITY BLOCK Date of Date of REMARKS ID NO. YEAR appointment acquiring to the post of Qualification TGT for the post of Lecturer UR 1 19831638 DHIRENDRA RAJ 01-Jan-55 1002007 East Vinod Nagar-SBV (Jai TGT N.SC. 929 1981-85 3-Nov-1983 16-Sep-78 Prakash Narayan) 2 19910899 BIKRAM SINGH 30-Apr-62 1106002 Dilshad Garden, Block C- TGT N.SC. 3850 1986-92 1-Oct-1991 30-Jun-84 SBV 3 19911129 DHYAN SINGH 25-Mar-67 2128008 Rani Jhansi Road-SBV TGT N.SC. 3854 1986-92 28-Oct-1991 4-Aug-89 ECONOMICS BHATI ALSO 4 19911176 PRABHAKAR 24-Feb-56 1104020 Gokalpuri-SKV TGT N.SC. 3855 1986-92 19-Nov-1991 31-Dec-81 CHANDRA AWASTHI 5 19910662 VINAY KUMAR 09-Nov-63 1002004 Shakarpur, No.2-SBV TGT N.SC. -

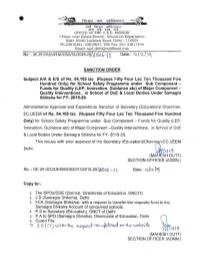

(03)/UEEM/OSD/31/2019-20/4506---1 L Date:- V21,1 E

• f-. T4"-1T q-zI t"-- TaTT 365-1-Z:175-1" Li al ara OFFICE OF THE U.E.E. MISSION I Floor, near Estate Branch, Education Department Distt. North Lucknow Road, Delhi - 110054 Ph.23810361, 23810647, Tele Fax:-011 23811442 Email:[email protected] No: - DE.29 (03)/UEEM/OSD/31/2019-20/4506---1 L Date:- V21,1 e\ SANCTION ORDER Subject: A/A & EIS of Rs. 54.105 lac (Rupees Fifty Four Lac Ten Thousand Five Hundred Only) for School Safety Programme under Sub Component - Funds for Quality (LEP, Innovation, Guidance etc) of Major Component - Quality Interventions, in School of DoE & Local Bodies Under Samagra Shiksha for FY- 2019-20. Administrative Approval and Expenditure Sanction of Secretary (Education)/ Chairman- EC,UEEM of Rs. 54.105 lac (Rupees Fifty Four Lac Ten Thousand Five Hundred Only) for School Safety Programme under Sub Component - Funds for Quality (LEP, Innovation, Guidance etc) of Major Component -Quality Interventions, in School of DoE & Local Bodies Under Samagra Shiksha for FY- 2019-20. This issues with prior approval of the Secretary (Education)/Chairm n-EC,UEEM Delhi. 11 0 (MA ESH DUTT) SECTION OFFICER (ADMN.) No: - DE.29 (03)/UEEM/OSD/31/2019-20/6604 Date:- )211)_111 Copy to:- 1. The DPOs/DDE (District), Directorate of Education, GNCTD 2. J.D (Samagra Shiksha), Delhi. 3. FCA (Samagra Shiksha), with a request to transfer the requisite fund to the Samagra Shiksha Account of concerned schools. 4. P.S to Secretary (Education), GNCT of Delhi. 5. P.A to SPD (Samagra Shiksha), Directorate of Education, Delhi. -

Chapter 3 Urban Housing and Exclusion

Chapter 3 Urban Housing and Exclusion © Florian Lang/ActionAid Gautam Bhan ● Geetika Anand Amogh Arakali ● Anushree Deb Swastik Harish 77 India Exclusion Report 2013-14 1. Introduction In different ways, however, these contrasting imaginations of housing eventually see it as an Housing is many things to many people. The asset to be accessed, consumed and used, be it by National Urban Housing and Habitat Policy (2007) households or developers, for use or exchange. sees housing and shelter as ‘basic human needs Housing is, in other words, an end unto itself. 1 next to only food or clothing’, putting makaan in However, housing is not just what it is but what it its familiar place beside roti and kapda. The United does. Declaring affordable housing to be a sector Nations agrees, speaking of the ‘right to adequate marked for priority lending, the Reserve Bank of housing as a human right owever, the ualifer— India spoke not just of access to housing but of the ‘adequate’—begins to push at the boundaries of what ‘employment generation potential of these sectors’.4 is meant when talking about ‘housing’. Adequacy Similarly, for the National Housing Bank, housing here includes a litany of elements: ‘(a) legal security is a basic need but also ‘a valuable collateral that of tenure; (b) availability of services, materials, can enable the access of credit from the fnancial facilities and infrastructure; (c) affordability; (d) market’.5 Others argue that housing is a vector habitability; (e) accessibility; (f) location; and to other developmental capabilities. Without it, 2 (g) cultural adequacy’. In the move from ‘house’ health, education, psycho-social development, to ‘housing’, the materiality of the dwelling unit cultural assimilation, belonging, and economic expands to include legal status, infrastructure, development are impossible. -

Short Communication KABP STUDY of MALARIA in the RURAL

ISSN: 0976-3325 Short Communication KABP STUDY OF MALARIA IN THE RURAL AREAS OF UTRAN, SURAT Verma Anupam1, Bansal RK2, Thakar Girish3, Modi Krishna4, Munshi Ankit4, Nagarsheth Mansi4 1Associate Professor, 2Profesor and Head, 3Regional Deputy Director, Health & Family Welfare Department, Govt. of Gujarat, 4Ex-Interns, Dept. of Community Medicine, SMIMER, Surat- 395010, Gujarat. Correspondence: [email protected] INTRODUCTION mosquitoes or harboured misconceptions thereof and Malaria an important public health problem affects all only 22.4 percent knew their breeding places. Only age groups and it is responsible for considerable 44% of the respondents were aware of the concept of morbidity and mortality in South East Asia and the intradomestic resting places. Indian subcontinent.1-2 Incidence of malaria 54.3 percent were aware of fever as a symptom of worldwide estimated to be 300-500 million cases malaria and 27.2 percent as fever with chills. each year, out of which about 90 percent occurring in Knowledge regarding other symptoms was relatively Sub-Saharan Africa and India3. Like India, malaria scant and another problem was the mentioning of problem in the Gujarat state has also remained quite other symptoms in the absence of the symptom of local and focal as per the current epidemiological fever. Other symptoms listed were headache (16%), situation4. Malaria kills between 1.1 to 2.7 million vomiting (13.6%), bodyache (10.4%), backache people worldwide each year and indirectly (4.8%), vertigo (4.8%) and anorexia (3.2%) or contributes to illness and death from respiratory symptoms related with other co-infections, yet infections, Diarrhoeal diseases and malnutrition3.