The Amazing Race

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I State Political Parties in American Politics

State Political Parties in American Politics: Innovation and Integration in the Party System by Rebecca S. Hatch Department of Political Science Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ John H. Aldrich, Supervisor ___________________________ Kerry L. Haynie ___________________________ Michael C. Munger ___________________________ David W. Rohde Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Political Science in the Graduate School of Duke University 2016 i v ABSTRACT State Political Parties in American Politics: Innovation and Integration in the Party System by Rebecca S. Hatch Department of Political Science Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ John H. Aldrich, Supervisor ___________________________ Kerry L. Haynie ___________________________ Michael C. Munger ___________________________ David W. Rohde An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Political Science in the Graduate School of Duke University 2016 Copyright by Rebecca S. Hatch 2016 Abstract What role do state party organizations play in twenty-first century American politics? What is the nature of the relationship between the state and national party organizations in contemporary elections? These questions frame the three studies presented in this dissertation. More specifically, I examine the organizational development -

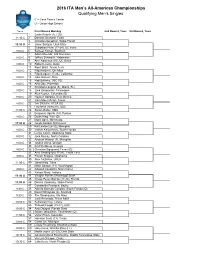

Finalbg Qual Sing DRAW2016

2016 ITA Men’s All-American Championships Qualifying Men's Singles C = Case Tennis Center U = Union High School Times First Round Monday 2nd Round, Tues 3rd Round, Tues 1 Justin Butsch (1), LSU 11:30 C 2 Dominic Bechard, Tulsa 3 Christian Seraphim, Wake Forest 10:30 U 4 Jaime Barajas, Utah State 5 Sebastian Heim (17-24), UC Irvine 8:00 C 6 Sameer Kumar, Stanford 7 Adam Moundir, Old Dominion 8:00 C 8 Jeffrey Schorsch, Valparaiso 9 Alec Adamson (10), UC Davis 8:00 C 10 Robert Levine, Duke 11 Ronit Bisht, Texas Tech 8:00 C 12 Filip Kraljevic, Ole Miss 13 Filip Bergevi (17-24), California 8:00 C 14 Jake Hansen, Rice 15 Rob Bellamy, USC (Q) 8:00 C 16 Alex Day, Princeton 17 Christian Langmo (5), Miami (FL) 8:00 C 18 Jack Schipanski, Tennessee 19 Alex Keyser, Columbia (Q) 8:00 C 20 Hayden Sabatka, New Mexico 21 John Mee (25-32), Texas 8:00 C 22 Joe DiGuilio, UCLA (Q) 23 Laurence Verboven, USC 11:00 C 24 Samm Butler, SMU 25 Benjamin Ugarte (14), Purdue 8:00 C 26 Dylan King, Yale (Q) 27 Matic Spec, Minnesota 11:30 U 28 Jacob Dunbar, Richmond 29 Kai Lemke (25-32), Memphis 8:00 C 30 Vadym Kalyuzhnyy, South Florida 31 Lucas Gerch, Oklahoma State 9:00 C 32 Jack Murray, North Carolina 33 Andrew Watson (3), Memphis 8:00 C 34 Jayson Amos, Oregon 35 Emil Reinberg, Georgia 9:00 C 36 Christian Sigsgaard, Texas (Q) 37 Alex Sendegeya (17-24), Texas Tech 9:00 C 38 Florian Bragusi, Oklahoma 39 Alex Cozbinov, UNLV 11:00 C 40 Jarod Hing, Tulsa 41 Mitch Stewart (11), Washington 9:00 C 42 Edward Covalschi, Notre Dame 43 Raheel Manji, Indiana 11:00 U 44 Vaughn Hunter, -

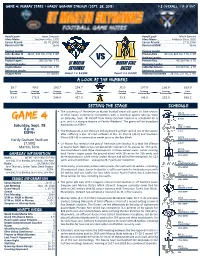

UTM Game Notes

GAME 4: MURRAY STATE • HARDY GRAHAM STADIUM (SEPT. 28, 2019) 1-2 OVERALL • 0-0 OVC Head Coach .............................Jason Simpson Head Coach ............................. Mitch Stewart Alma Mater ................... Southern Miss, 1995 Alma Mater ................... Valdosta State, 2005 Career Record ............................ 81-70 (14th) Career Record .............................. 17-31 (5th) Record at UTM ...................................... Same Record at MUR ...................................... Same Passing Leader Passing Leader John Bachus III .... 38-67, 443 Yds, 2 TD, 3 INT Preston Rice .........83-116, 824 Yds, 7 TD, 2 INT Rushing Leader Rushing Leader Peyton Logan ...................... 28/216 Yds, 3 TD vs Preston Rice ........................ 45/229 Yds, 0 TD Receiving Leader UT MARTIN MURRAY STATE Receiving Leader Jaylon Moore ........................ 5/122 Yds, 1 TD SKYHAWKS RACERS LaMartez Brooks ................. 10/254 Yds, 3 TD Defensive Leader Defensive Leader JaQuez Akins ................................31 Tackles Record: 1-2, 0-0 OVC Record: 2-2, 0-0 OVC Anthony Koclanakis .....28 Tkls, 2.0 TFL, 1 INT A LOOK AT THE NUMBERS 18.7 99.0 160.7 259.7 31.0 197.0 266.0 463.0 Scoring Rushing Passing Total Scoring Rushing Passing Total Offense Yards/Gm Yards/Gm Offense Defense Defense/Gm Defense/Gm Defense 33.8 178.5 249.0 427.5 33.8 145.8 252.5 398.2 SETTING THE STAGE SCHEDULE • The University of Tennessee at Martin football team will open its 28th season AUG. 29 of Ohio Valley Conference competition with a matchup against Murray State NORTHWESTERN STATE GAME 4 on Saturday, Sept. 28. Kickoff from Hardy Graham Stadium is scheduled for 6 W, 42-20 p.m. and is a marque feature of Family Weekend. -

Organizing for America

Organizing for America Barbara Trish Grinnell College Prepared for delivery at The State of the Parties Conference, October 15‐16, 2009 Akron OH Organizing for America As president, Barack Obama has the potential to refashion his party, as do all who hold that position. In his case, to the extent that he can marshal the power of the organization which was seen as key to his electoral success into the realm of governing, he can alter the basic framework of Democratic party organizational politics, including the fundamental relationship between the president and the party. The task, however, seems fundamentally difficult, perhaps hopeless. Indeed, some might even argue that it is undesirable. At a minimum the difficult challenge of sustaining a movement over time and the underlying logic of activism, both compounded by qualities of the current political climate, recommend caution in predicting success, especially as borne out in a monumental reshaping of party politics. This paper explores Organizing for America (OFA), the current iteration of Obama for America, the president’s much‐touted campaign organization. When OFA took shape in early 2009, its entrance into the political world was newsworthy and cast in both positive and negative light. On one hand, it was heralded as a brilliant and transformative move by Obama insiders David Plouffe and Mitch Stewart, seeking to enlist the people who had fueled the election campaign – namely, those on the famed e‐mail list – in the business of governing. On the other hand, OFA was described as a potentially nefarious organization, with unthinking members pledged to support their leader, and an organizational 1 precedent no‐less‐threatening than Chairman Mao’s Red Guards.1 The political science community weighed in with decidedly less hyperbole. -

Grim Map Demographics Face Dems

V16, N30 Thursday, April 7, 2011 Grim map demographics face Dems have essentially pledged to GOP can rely on follow basic guidelines by former Secretary of State Todd population, not Rokita to build districts based politics for favorable on “communities of inter- est,” county lines and nesting legislative maps House districts in Senate dis- tricts. It is the demographics By BRIAN A. HOWEY that pose a daunting chal- INDIANAPOLIS - New lenge to House Democrats. Congressional and legislative These include: maps are being • The 40 Democratic-held forged in the Indiana House districts gained Indiana House a total of 4,681 people, an and Senate and average of 117 per district. are expected to • The 60 GOP-held Indiana be made public House districts gained a total next week. of 398,636 people; an average Whatever the of 6,644 per district. Note the popula- specifics are, • The state total popula- tion loss along the new maps tion gain was 403,317: an the Lake Michi- will likely paint average of 4,033 per district. gan shore and a grim picture • 30 House districts lost in South Bend, for Indiana population: 21 Democrat dis- all Democratic Democrats. tricts and 9 GOP districts. strongholds. This • Nine of the top 10 pop- Howey Politics ulation-losing districts – and Indiana analysis is not a partisan 15 of the top 20 - are held by one, as Gov. Mitch Daniels and House Speaker Brian Bosma Continued on page 3 Shutdowns, walkouts & civility in politics By MARK SOUDER FORT WAYNE - “While Henry lives another bad “We want (Medicaid) to be constitution would be formed and saddled forever on us. -

CPD Disciplines Griggs, Tyson by TONY EUBANK Has Been Demoted from Crime Scene Techni- Superior Or Internal Investigation Officer

THURSDAY 161st YEAR • NO. 12 MAY 14, 2015 CLEVELAND, TN 38 PAGES • 50¢ Reminder CU contractor CPD disciplines Griggs, Tyson By TONY EUBANK has been demoted from crime scene techni- Superior or Internal Investigation Officer. to begin AMR Banner Staff Writer cian (Level 26) to the patrol division as a Level In his disciplinary action, Tyson was given 25 patrol officer. a verbal reprimand for violating Policy 04- Cleveland Police Officer Jeffery Griggs has According to the DA’s report, Griggs was A/LL, Failure to Report Violations. As part of work Monday been demoted and CPD Lt. Steve Tyson has found to be in violation of the following CPD his discipline, Tyson has been reassigned to been reassigned as a result of an Internal policies: the patrol division. From Staff Reports Affairs investigation concerning their involve- —Policy 04-A/LL Subsection 4-HH, Maddux submitted his request for retire- A contractor working with ment with an incident involving Griggs’ wife Truthfulness; ment Tuesday. Cleveland Utilities will begin and former Chief Dennis Maddux. —Policy 05-A/LL, Prohibited Behaviors The disciplinary decision in the cases of installing automatic-read water The CPD announced the disciplinary action Subsection; Tyson and Griggs were made by Interim Chief meter registers and transmitters, this morning, finding Griggs to be in violation —Disobeying Orders; and according to an announcement of several department policies, and as a result —Compliance with Direct Orders of Griggs Tyson by Philip E. Luce, manager, CU See CPD, Page 5 Water and Wastewater Division Engineering. Baird Construction Company Inc. will be installing the EMS eyes CHS faces AMR/AMI equipment on existing water meters throughout the por- tion of the Cleveland Utilities system to year-end water system located inside the Cleveland corporate limits over the next 9 months. -

Democratic Party Organization in the Twenty-First Century

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2017 Dinosaurs for the Digital Age: Democratic Party Organization in the Twenty-First Century Aaron B. Shapiro The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2257 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] DINOSAURS FOR THE DIGITAL AGE: DEMOCRATIC PARTY ORGANIZATION IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY by AARON SHAPIRO A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Political Science in partial fulfillment for the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York. i ©2017 AARON SHAPIRO All Rights Reserved ii Dinosaurs for the Digital Age: Democratic Party Organization in the Twenty-First Century by Aaron Shapiro This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Political Science in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date [Frances Fox Piven] Chair of Examining Committee Date [Alyson Cole] Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: John Mollenkopf James Jasper THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Dinosaurs for the Digital Age: Democratic Party Organization in the Twenty-First Century by Aaron Shapiro Advisor: Frances Fox Piven Abstract: This dissertation traces Democratic Party organization roughly over the Obama era. It conceptualizes the party at the national, state, and local level, with a particular focus on Ohio. -

8/25/08 Roger Simon, Politico's Chief Political Columnist, Has Been a Respected Name in American Journalism Since the 1970S —

8/25/08 Roger Simon, Politico's chief political columnist, has been a respected name in American journalism since the 1970s — and an authoritative voice in American politics for just as long. After the historic contest between Hillary Rodham Clinton and Barack Obama finally came to an end in June, Simon launched an intensive effort to get behind the scenes — and to the bottom — of what happened and why. He interviewed scores of well-placed people at all levels of both campaigns, many of whom have been sources of his for years. This project, which Simon named "Relentless" to reflect what he saw as the animating spirit of Obama's remarkable campaign, is the result of Simon's two years of reporting on this campaign, and decades of observing political personalities in action. – John F. Harris Introduction: The path to the nomination By: Roger Simon August 24, 2008 09:09 AM EST In the summer of 2006, Patti Solis Doyle offered David Axelrod a job. Hillary Clinton was running for reelection to the Senate and Solis Doyle was her campaign manager, but everybody knew Clinton was soon going to run for president. And Clinton wanted Axelrod onboard. Axelrod was a highly experienced and successful political consultant and just what Clinton needed. But he declined. Presidential campaigns were mentally taxing, physically exhausting and emotionally draining. There were easier ways to make a buck. Unless. “I wasn’t planning to work in a presidential race,” Axelrod told me, “but if Barack might run, well, he would be the only guy to cause me to get in.” It was not impossible. -

Obama's Legacy: a Research in the History of Technological Change, Internet and Data Gathering from the Perspective of a Political Star

Obama's Legacy: a Research in the History of Technological Change, Internet and Data Gathering from the Perspective of a Political Star. By Rik van Eijk 10003025 Supervisor: dhr. dr. E.F. van de Bilt University of Amsterdam 2015 1 Introduction “I hope we will use the Net to cross barriers and connect cultures...” ...was the answer by Tim Berners-Lee, the major inventor of the World Wide Web, when CNN asked him what he thought the internet's biggest impact would be (CNN 2005). In 1990, the general public was introduced to the World Wide Web, developed in the rooms of CERN in Geneva. Through this world wide web, people could talk, discuss and enhance their opinion on every subject that they wanted. This world wide web became quickly known as the internet. Academics could simply send and peer-review their colleague's publications. E-mail introduced a fast way to send text to a particular person; families all over the world were able to quickly (re)connect when instant messengers took over and webcams were introduced. Companies got involved in the business and started their own websites. Sites became less static, introduced pictures and video’s and designers and programmers improved websites to optimize the user experience. Games focused more and more on a multiplayer function, because the internet allowed people all over the world to play with and against each other. SixDegrees launched personal websites in the 90’s, just like Facebook or Twitter offer today. By selling advertorials based on a specific user data, internet companies, such as Google and Yahoo, form a billion dollar industry. -

Housed at the Democratic National Committee, the Sycophantic OFA Is

"! Perpetual Campaign ORGANIZING for SOCIALISM Housed at the Democratic National Committee, the sycophantic OFA is doing everything it can to milk the cult of personality Barack Obama created during the 2008 campaign. Is it really political activism—or a massive ego trip? by Matthew Vadum iberals responded with howls now the Left is aiming to have the for government spending on whatever of indignation when Rudy last laugh. project is fashionable in leftist circles Giuliani mocked community Conservatives are justifi ably suspicious that day. organizers at last year’s of Obama-style community organizing, Republican National Convention. so it’s no surprise that Organizing MAKING SOCIALISM COOL The former mayor of New York City for America (OFA) is the kind of OFA attempts to make progressive said that Barack Obama “worked as a organization that makes those on the agitation hip and mainstream. community organizer.” Right uneasy. OFA tries to cross Howard Dean-style “What?” Giuliani said as he burst out Prior to last year, most Americans had activism with community organizing. laughing. Speaking over a boisterous never heard of community organizing. It seeks to improve on the Internet- crowd, he continued, “He worked—I But what exactly is community based success of Dean’s insurgent 2004 said—I said—OK, OK. Maybe this is the organizing? presidential campaign that propelled the fi rst problem on the resume. He worked In the specifi c sense the Community then-unknown governor from a sparsely as a community organizer.” Organizer-in-Chief uses the term, it’s populated state to frontrunner at the GOP vice presidential candidate Sarah not about church bake sales, picking up beginning of that year’s Democratic Palin, former mayor of tiny Wasilla, litter, little leagues or parent-teacher primary season. -

16 • 2015 MURRAY STATE FOOTBALL Head Coach

TABLE OF Contents MEDIA INFORMATION ___________________________3 2015 MSU FOOTBALL gUIDE at A gLANcE___________________________________4 The 2015 Murray State Football Guide was designed and produced by the MSU Athletics Department in Murray, Ky., using Adobe InDesign and Adobe __________________________ 5-6 NUMERIcAL ROSTER Photoshop. ALphABETIcAL ROSTER ________________________ 7-8 ROSTER BREAkDOwN ________________________ 9-10 pROJEcT cOORDINATOR/DESIgN 2015 Opponents __________________________ 11-14 Parker Griffith head cOAch mitch stewart _________________ 15-16 EDITOR ___________ 17-23 assistant cOAches/support staff Sherry Griffith RETURNINg starters _______________________ 24-30 RETURNINg LETTERwINNERS _________________ 31-51 cONTRIBUTORS NEwcOMERS ______________________________ 52-59 Jessica Cary, Ryan Haage, Morgan Harding, Matt Kelly, Sarah Marshall, Logan 2014 statisticS ___________________________ 60-63 Loss, Meagan Short, Dave Winder, MSU Football Staff _____________________ 64-67 YEAR-by-YEAR LEADERS RESEARch ASSISTANcE season REcORDS __________________________ 68-70 Kevin Britton, Jessica Cary, Ryan Haage, Morgan Harding Sarah Marshall, Ryne TEAM/INDIvidual REcORDS __________________ 71-72 Rickman, Logan Ross, Marshall Smith, David Snow, RUShINg REcORDS ____________________________ 73 REcEIvINg REcORDS ___________________________ 74 phOTOgRAphY Lance Allison, Eric Benson, Tab Brockman, John Brush, Jessica Cary, Patrick passing REcORDS _____________________________ 75 Clark, Art Cripps, Cindi Cripps, Michael Dann, Michael -

Eastern Illinois Panther Football

October 31, 2015 • Eastern Illinois at Murray State • Page 1 • www.eiupanthers.com • #EIUBleedBlue EASTERN ILLINOIS PANTHER FOOTBALL Contact: Rich Moser • [email protected] • (217) 581-7480 • Fax (217) 581-7001 • www.EIUpanthers.com GAME 9 Panthers Look To Continue OVC Win Streak EIU Visit Murray State For Halloween Contest Eastern Illinois at Murray State Stewart Stadium (16,800) • Murray, Ky. October 31, 2015 • 1 p.m. • TV: OVC Digital Network THE GAME COACHES: Kim Dameron (Arkansas, 1983) • Eastern Illinois remained undefeated in the Ohio Valley Conference race as the Panthers EIU Record .....................9-10 (2nd year) moved to 4-0 in the conference with a 51-20 win over Tennessee Tech. The game was OVC Record .....................9-3 (2nd year) the 100th homecoming celebration on campus. EIU kept pace with Jacksonville State vs. Murray State ................................ 1-0 and Eastern Kentucky with all three teams now 4-0. JSU and EKU play this weekend. • Some members of the Eastern Illinois coaching staff will celebrate a homecoming of Mitch Stewart (Valdosta State, 2005) sorts this weekend when the Panthers play at Murray State. Head coach Kim Dameron MUR Record ..................... 2-5 (1st year) along with assistant coaches Mark Hutson and Danny Nutt are all former assistant coaches OVC Record ...................... 1-3 (1st year) at Murray State under head coach Houston Nutt in the 1990s. Overall Record ...............................Same • Kamu Grugier-Hill was named the Ohio Valley Conference Defensive Player of the vs. Eastern Illinois ............................. 0-0 Week as the linebacker helped the Panthers force six turnovers in the win over Tennessee SERIES Tech.