Democratic Party Organization in the Twenty-First Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elections Director Ohio Democratic Party Columbus, Ohio About Ohio

Elections Director Ohio Democratic Party Columbus, Ohio About Ohio Over the next two years the Ohio Democratic Party (ODP) will build an organization to win highly consequential elections up and down the ballot. With new leadership comes a new vision for our Party, refocusing on the core fundamentals that move the needle. ODP is building back better as a focused, modern, and nimble force to elect Democrats statewide now and in the future. Ohio is a top tier U.S. Senate pick up opportunity for national Democrats because of retiring Republican incumbents. The battle to save the Senate majority will be fought in Ohio. 2022 offers the chance to take control of the Ohio Supreme Court, make gains under new legislative maps, and win control of state government constitutional including Governor/Lt. Governor, Attorney General, Secretary of State, Treasurer, and Auditor. These opportunities give Democrats in Ohio early and strategic gains in rebuilding the Ohio Democratic Party. About the Opportunity The Ohio Democratic Party is seeking a talented, passionate professional to build an elections operation that will reimagine how we connect with, train, support, and activate volunteers and candidates in Ohio. In partnership with the Chair and the Executive team, the Elections Director will lead a highly integrated team of field, training, data, and digital staff responsible for building a volunteer organization that can be maintained cycle to cycle. They will set strategic goals for 2021, 2022, and manage the engagement of multiple in-state entities (County parties, progressive groups, caucuses) candidate campaigns across the ballot, and a variety of local, statewide, and national stakeholders. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly fi'om the original or copy submitted- Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from aity type of conçuter printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to r i^ t in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9427761 Lest the rebels come to power: The life of W illiam Dennison, 1815—1882, early Ohio Republican Mulligan, Thomas Cecil, Ph.D. -

SENSITIVE Is, MUR NO

FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION . ^ 2D!2 j;;in-B ni 1.2 OFFICE v;^ 'z:.zzzz IN THE MATTER OF: C I- ?i i::. COLUMBUS METROPOLITAN CLUB; OHIO REPUBLICAN PARTY; OHIO DEMOCRATIC PARTV. SENSITIVE is, MUR NO. ^ (0 • •' rr! CJ 2i:~rnr-. Q I. As explained more fully below, the Columbus Metropolitan Club (CMC), ^ May 2$ ^ 2012 violated the Federal Election Campaign Act (FEGA), 2 U.S.C. § 441 b(a), by p(«Viding the: Ohio Republican Party'and Ohio Democratic Party, and their presuniptive, presidential candidates, Mitt Romney and Barack Obama, respectively, corporate campaign contributions. The Ohio Republican Party and Ohio Democratic Party are also in violation of the FECA because they participated in arranging, and accepting, these unlavi/ful corporate campaign contributions. See 2 U.S.C. § 441b(a)> 2. As explained more fully below, CMC violated the FECA and its implementing regulations by inviting, authorizing and allowing both the Ohio Republican Party and the Ohio Republican Party, through their chairs, Robert t. Bennett and Chris Redfern, respectively, to make campaign-related speeches to an unrestricted audience that included the generai public. See FEC Advisory Opinion 1996-11. CMC accomplished this illegal end by staging a "forum," which closely resembled a debate, between Bennett and Redfern on May 23, 20:1 !2, which was advertised by CMC as "Presidential Politics in O-H-l-O," and which the general public was invited and allowed to attend. Further, CMC filmed (Le., electronically capturing through video and audio recording) the forum in its entirety with plans to post this filming (as described above) on its unrestricted web page, which is open to and. -

Repudiation! the Crisis of United States Civil War Debt, 1865-1870

Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva Pierre du Bois Foundation GOVERNMENT DEBT CRISES: POLITICS, ECONOMICS, AND HISTORY December 14-15, 2012 Repudiation! The Crisis of United States Civil War Debt, 1865-1870 Dr. Franklin Noll President Noll Historical Consulting, LLC Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2196409 Repudiation! The Crisis of United States Civil War Debt, 1865-1870 Dr. Franklin Noll President Noll Historical Consulting, LLC 220 Lastner Lane Greenbelt, MD 20770 USA Email: [email protected] Website: www.franklinnoll.com The author would like to thank Bruce Baker, Jane Flaherty, and Julia Ott for their comments. Abstract: From 1865 to 1870, a crisis atmosphere hovered around the issue of the massive public debt created during the recently concluded Civil War, leading, in part, to the passage of a Constitutional Amendment ensuring the “validity of the public debt.” However, the Civil War debt crisis was not a financial one, but a political one. The Republican and Democratic Parties took concerns over the public debt and magnified them into panics so that they could serve political ends—there was never any real danger that the United States would default on its debt for financial reasons. There were, in fact, three interrelated crises generated during the period: a repudiation crisis (grounded upon fears of the cancellation of the war debt), a repayment crisis (arising from calls to repay the debt in depreciated currency), and a refunding crisis (stemming from a concern of a run on the Treasury). The end of the Civil War debt crisis came only when there was no more political advantage to be gained from exploiting the issue of the public debt. -

The Crisis of United States Civil War Debt, 1865-1870

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Repudiation: The Crisis of United States Civil War Debt, 1865-1870 Noll, Franklin December 2012 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/43540/ MPRA Paper No. 43540, posted 03 Jan 2013 04:20 UTC Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva Pierre du Bois Foundation GOVERNMENT DEBT CRISES: POLITICS, ECONOMICS, AND HISTORY December 14-15, 2012 Repudiation! The Crisis of United States Civil War Debt, 1865-1870 Dr. Franklin Noll President Noll Historical Consulting, LLC Repudiation! The Crisis of United States Civil War Debt, 1865-1870 Dr. Franklin Noll President Noll Historical Consulting, LLC 220 Lastner Lane Greenbelt, MD 20770 USA Email: [email protected] Website: www.franklinnoll.com The author would like to thank Bruce Baker, Jane Flaherty, and Julia Ott for their comments. Abstract: From 1865 to 1870, a crisis atmosphere hovered around the issue of the massive public debt created during the recently concluded Civil War, leading, in part, to the passage of a Constitutional Amendment ensuring the “validity of the public debt.” However, the Civil War debt crisis was not a financial one, but a political one. The Republican and Democratic Parties took concerns over the public debt and magnified them into panics so that they could serve political ends—there was never any real danger that the United States would default on its debt for financial reasons. There were, in fact, three interrelated crises generated during the period: a repudiation crisis (grounded upon fears of the cancellation of the war debt), a repayment crisis (arising from calls to repay the debt in depreciated currency), and a refunding crisis (stemming from a concern of a run on the Treasury). -

The Jacksonian Roots of Modern Liberalism

Thomas S. Mach. "Gentleman George" Hunt Pendleton: Party Politics and Ideological Identity in Nineteenth-Century America. Kent: Kent State University Press, 2007. ix + 307 pp. $39.95, cloth, ISBN 978-0-87338-913-6. Reviewed by Thomas F. Jorsch Published on H-SHGAPE (April, 2008) Ohio Democrat George Pendleton was a con‐ cratic Party. After one term in the state senate, siderable force in American politics during the Pendleton won a seat in the U.S. House of Repre‐ latter half of the nineteenth century. He served sentatives. Here, his political ideology matured four terms in the U.S. House of Representatives through the battle over admittance of Kansas as a (1857-65), ran as the Democratic vice presidential state under the Lecompton Constitution, where he nominee alongside George McClellan in the elec‐ weighed the conflicting issues of popular tion of 1864, entered the 1868 Democratic Conven‐ sovereignty, constitutional rules regarding state‐ tion as the presidential frontrunner (he did not hood, and the sectionalism pulling his party apart. win the nomination), served one term in the U.S. Secession and Civil War strengthened the states' Senate (1879-85), and authored the 1883 civil ser‐ rights aspect of his Jacksonianism and catapulted vice legislation that bears his name. Despite him to leadership positions. During the secession Pendleton's political significance, no scholarly bi‐ crisis, Pendleton called for union through peace‐ ography of "Gentleman George" exists. Thomas S. ful compromise. Short of that, he preferred a Mach, professor of history at Cedarville Universi‐ peaceful splitting of the Union based on Southern ty, flls this void with a well-researched account states' rights to federal force maintaining the that stresses Pendleton's commitment to Jacksoni‐ Union. -

Waltz Florida Dems PPP Letter (/Uploadedfiles/Waltzsba FDP PPP)

October 8, 2020 The Honorable Hannibal “Mike” Ware Inspector General U.S. Small Business Administration 409 3rd Street SW Washington, D.C. 20416 Dear Inspector General Ware: The Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) was designed to provide a direct incentive for small businesses to keep their workers on the payroll. Congress intended the program to provide relief to America’s small businesses quickly, and demand for the program was extraordinary: PPP lenders approved more than 1.6 million loans totaling more than $342 billion in the program’s first two weeks, according to your office.1 The Small Business Administration subsequently released data that shows a political organization may have taken advantage of the program’s expedited nature to obtain funds for which they were ineligible. Specifically, the data show a Democrat-affiliated political organization in Florida applied for and received PPP funds, contrary to the intent of Congress that the program should support small businesses, non-profits, veterans’ organizations, and tribal concerns. The Small Business Administration issued regulations that specifically prohibit “businesses primarily engaged in political or lobbying activities” from receiving PPP loans.2 Despite this restriction, the Florida Democratic Party (FDP) applied for and received a PPP loan worth $780,000.3 The details of the FDP loan application raise serious questions as to whether the applicant intentionally misled the Small Business Administration in order to obtain PPP funds. FDP filed its application under the identity of a non-profit organization called the “Florida Democratic Party Building Fund, Inc.” The Florida Democratic Party Building Fund, Inc. is a separate legal entity from the Florida Democratic Party, but Florida state records show the party formed the not-for-profit corporation in April of 2019 to construct, own or operate “the headquarters of the state executive committee of the Florida Democratic Party and related political organizations.”4 Documents show the Florida Democratic Party Building Fund, Inc. -

1 in the United States District Court

Case 5:20-cv-00046-OLG Document 78 Filed 06/12/20 Page 1 of 22 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS SAN ANTONIO DIVISION JARROD STRINGER, et al., § Plaintiffs, § § v. § No. SA-20-CV-46-OG § RUTH R. HUGHS, et al., § Defendants. § DEFENDANTS’ RESPONSE IN OPPOSITION TO INTERVENORS’ MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT AND COUNTER-MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT DISMISSING INTERVENORS Intervenors1 lack standing and their sole claim is meritless. Their Motion for Summary Judgment, Dkt. 77—which presents no new facts or authority to alter this conclusion—should be denied, and the Court should enter summary judgment dismissing Intervenors from this case. FACTUAL BACKGROUND I. Texas Voter Registration Voter registration in Texas is governed by a carefully considered statutory framework. Importantly here, “[a] registration application must be in writing and signed by the applicant.” TEX. ELEC. CODE § 13.002(b); see also id. § 65.056(a) (allowing the affidavit on a provisional ballot to serve as a voter-registration application if it contains the necessary information). Likewise, any request to change voter-registration information must also be in writing and signed. Id. § 15.021(a). The signatures may then be used for, inter alia, investigations of fraud or identity theft, consideration of absentee ballots, or if there are any problems with electronically captured signatures. Stringer I, No. 5:16-cv-00257 (W.D. Tex.) (“Stringer I”), Dkt. 77-1 at 82; 80-1 at 61, 71-72.2 1 “Plaintiff-Intervenors” or “Intervenors” refers to the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee (“DSCC”), Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee (“DCCC”), and Texas Democratic Party (“TDP”). -

I State Political Parties in American Politics

State Political Parties in American Politics: Innovation and Integration in the Party System by Rebecca S. Hatch Department of Political Science Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ John H. Aldrich, Supervisor ___________________________ Kerry L. Haynie ___________________________ Michael C. Munger ___________________________ David W. Rohde Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Political Science in the Graduate School of Duke University 2016 i v ABSTRACT State Political Parties in American Politics: Innovation and Integration in the Party System by Rebecca S. Hatch Department of Political Science Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ John H. Aldrich, Supervisor ___________________________ Kerry L. Haynie ___________________________ Michael C. Munger ___________________________ David W. Rohde An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Political Science in the Graduate School of Duke University 2016 Copyright by Rebecca S. Hatch 2016 Abstract What role do state party organizations play in twenty-first century American politics? What is the nature of the relationship between the state and national party organizations in contemporary elections? These questions frame the three studies presented in this dissertation. More specifically, I examine the organizational development -

Portage County Democratic Party News and Notes - May 2019

6/28/2020 https://my.blueutopia.com/admin/modules/email/simpleview.php?id=9 Portage County Democratic Party News and Notes - May 2019 Dear %firstname%, First and foremost, I want to extend a sincere congratulations to Melissa Roubic on her victory in last month's Primary Election for Municipal Court Judge. No one filed to challenge her by the deadline, which means she will be unopposed this November and will take her seat on the bench in January. I am proud of the races Melissa and Stephen Smith ran for this seat, and I know she will represent us well in this new capacity. Congratulations too to all who won their races for municipal seats and now move on to the General Election. Portage County residents will have a number of great options this fall when they go to the ballot to choose their local leaders, and I look forward to working to elect these fine Democrats in the months ahead. Below, you will find several opportunities for engagement happening in the weeks ahead. I hop you'll take advantage of them and keep up the good work we're doing to lead Portage County forward. If there are items you'd like us to share in future newsletters, please don't hesitate to let us know by responding to this email. Thank you for all you do to keep our Party - and Portage County - strong. Forward, Dean DePerro, Chairman * * * https://my.blueutopia.com/admin/modules/email/simpleview.php?id=9 1/7 6/28/2020 https://my.blueutopia.com/admin/modules/email/simpleview.php?id=9 Upcoming Events Clyde Birthday Fundraiser feat. -

Ohio Luck Times 1985-1986 Government Directory

Ohio luck Times 1985-1986 Government Directory Published by me Ohio Trucking Association _ a different kind of downtown tavern i 190 7323149 66 Lynn Alley between Third & High 224-6600 Open Monday thru Friday 11am to 11pm Full Menu served until 10pm Free hors d'oeuvres Friday night "Best Spread in Columbus" says Columbus Monthly Private Banquet Rooms Available ^iwfe^::^ ••••••,..-==g "•'r^'mw.rffvirrr-'i-irii w» Dhto luck Times BHT )lume 34 Number 1 Welcome from the 71 Winter 1985 Ohio Trucking Association OHIO TRUCKING ASSOCIATION The tenth edition of the Ohio Truck Times Government Direc Published biennially in odd-numbered tory is out, and we thank you for your patience. Our goal is always to years publish the directory as close to the opening of each Ohio General PUBLICATION STAFF Assembly as we can while also creating the most complete reference Donald B. Smith, Publisher guide possible. Somewhere between the two lie many last-minute David F. Bartosic, Editor changes, appointments, assignments and other delays. I hope it was worth the wait. EDITORIAL AND BUSINESS OFFICES Almost 20 years ago the Ohio Trucking Association began this directory with photos and biographical sketches of Ohio legisla Suite 1111 tors. Since then, we have expanded it to include not only those who 50 West Broad Street make the laws, but also those who administer them. Obviously Columbus, Ohio 43215 there are many state officials under this aegis, many more than we Phone: 614/221-5375 could accommodate with this issue. ASSOCIATION STAFF New additions for this biennium include members of the Pub lic Utilities Commission, the Industrial Commission and Bureau of Donald B. -

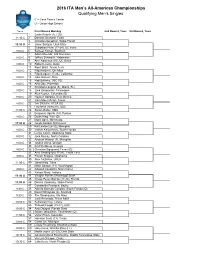

Finalbg Qual Sing DRAW2016

2016 ITA Men’s All-American Championships Qualifying Men's Singles C = Case Tennis Center U = Union High School Times First Round Monday 2nd Round, Tues 3rd Round, Tues 1 Justin Butsch (1), LSU 11:30 C 2 Dominic Bechard, Tulsa 3 Christian Seraphim, Wake Forest 10:30 U 4 Jaime Barajas, Utah State 5 Sebastian Heim (17-24), UC Irvine 8:00 C 6 Sameer Kumar, Stanford 7 Adam Moundir, Old Dominion 8:00 C 8 Jeffrey Schorsch, Valparaiso 9 Alec Adamson (10), UC Davis 8:00 C 10 Robert Levine, Duke 11 Ronit Bisht, Texas Tech 8:00 C 12 Filip Kraljevic, Ole Miss 13 Filip Bergevi (17-24), California 8:00 C 14 Jake Hansen, Rice 15 Rob Bellamy, USC (Q) 8:00 C 16 Alex Day, Princeton 17 Christian Langmo (5), Miami (FL) 8:00 C 18 Jack Schipanski, Tennessee 19 Alex Keyser, Columbia (Q) 8:00 C 20 Hayden Sabatka, New Mexico 21 John Mee (25-32), Texas 8:00 C 22 Joe DiGuilio, UCLA (Q) 23 Laurence Verboven, USC 11:00 C 24 Samm Butler, SMU 25 Benjamin Ugarte (14), Purdue 8:00 C 26 Dylan King, Yale (Q) 27 Matic Spec, Minnesota 11:30 U 28 Jacob Dunbar, Richmond 29 Kai Lemke (25-32), Memphis 8:00 C 30 Vadym Kalyuzhnyy, South Florida 31 Lucas Gerch, Oklahoma State 9:00 C 32 Jack Murray, North Carolina 33 Andrew Watson (3), Memphis 8:00 C 34 Jayson Amos, Oregon 35 Emil Reinberg, Georgia 9:00 C 36 Christian Sigsgaard, Texas (Q) 37 Alex Sendegeya (17-24), Texas Tech 9:00 C 38 Florian Bragusi, Oklahoma 39 Alex Cozbinov, UNLV 11:00 C 40 Jarod Hing, Tulsa 41 Mitch Stewart (11), Washington 9:00 C 42 Edward Covalschi, Notre Dame 43 Raheel Manji, Indiana 11:00 U 44 Vaughn Hunter,