Organizing for America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Bottom Conservancy • Arkansas Wildlife Federation

American Bottom Conservancy • Arkansas Wildlife Federation • Audubon Chapter of Minneapolis • Biodiversity Project • Center for Neighborhood Technology • Citizens Against Widening the Industrial Canal • Committee on the Middle Fork Vermilion River • Delta Chapter Sierra Club • Delta Waterfowl Foundation • Friends of the Kaw/Kansas Riverkeeper • Friends of the North Fork and White Rivers • Great Rivers Environmental Law Center • Gulf Restoration Network • Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy • Iowa Chapter Sierra Club • Iowa Environmental Council • Iowa Rivers Revival • Jesus People Against Pollution • Kansas Natural Resource Council • Kansas Wildlife Federation • Kentucky Resources Council • Lake Pontchartrain Basin Foundation • Louisiana Bucket Brigade • Louisiana Environmental Action Network • Lower Mississippi Riverkeeper • Lower Mississippi River Foundation • Lower 9th Ward Center for Sustainable Engagement and Development • Mid South Fly Fishers • Milwaukee Riverkeeper • Minnesota Conservation Federation • Minnesota Division of Izaak Walton League of America • Minnesota Ornithologists' Union • Mississippi Chapter of the Sierra Club • Mississippi River Corridor • Mississippi River Fund • Missouri Coalition for the Environment • Missouri River Initiative of Izaak Walton League of America • Missouri River Waterfowlers Association • Open Space Council • Prairie Rivers Network • South Dakota Wildlife Federation • Tennessee Clean Water Network • Wolf Rive Conservancy • Yell County Wildlife Federation June 21, 2011 President Barack -

The American Democratic Party at a Crossroads MATT BROWNE / JOHN HALPIN / RUY TEIXEIRA

The American Democratic Party at a Crossroads MATT BROWNE / JOHN HALPIN / RUY TEIXEIRA AMERICAN DEMOCRATIC PARTY* * It is neither a parliamentary party nor a membership organization, but rather coordinated by a series of committees. Official website: The Democratic National Committee (DNC): www.democrats.org; The Democratic Governors’ Association (DGA): www.democraticgovernors.org; The Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee (DSCC): www.dscc.org; The Democratic Congressional Campaign Commit- tee (DCCC): www.dccc.org; The Democratic Legislative Campaign Committee (DLCC): www.dlcc.org; The Association of State Democratic Chairs (ASDC): www.democrats.org/asdc Party leader: Governor Tim Kaine is the Chairman of the DNC. Founded: 1828 Electoral resonance 2008: Senate: 57; House: 257 parliamentary elections: 2006: Senate: 49; House: 233 2004: Senate: 44; House: 202 Government President Barack Obama was elected 44th President participation: of the United States on November 4, 2008, beating his Republican rival by 365 electoral votes to 173. He assumed office on January 20, 2009, returning the Democrats to the executive branch for the first time in eight years. 144 Browne/Halpin/Teixeira, USA ipg 4 /2010 Foundations of the Democratic Party The Democratic Party of the United States was founded in 1828 and traces its philosophy back to Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson, both of whom styled themselves as advocates of the »common man.« Despite these origins, the Democratic Party has not always been the most pro- gressive party in the us. For example, the Republican Party of Abraham Lincoln, not the Democrats, took the lead in ending slavery in the coun- try. And in the Progressive Era (roughly 1890–1920), the Republicans, with figures such as Teddy Roosevelt and Bob La Follette, again took the lead in fighting corruption, reforming the electoral process, curbing the power of big capital, and developing social welfare programs. -

Executive Branch

EXECUTIVE BRANCH THE PRESIDENT BARACK H. OBAMA, Senator from Illinois and 44th President of the United States; born in Honolulu, Hawaii, August 4, 1961; received a B.A. in 1983 from Columbia University, New York City; worked as a community organizer in Chicago, IL; studied law at Harvard University, where he became the first African American president of the Harvard Law Review, and received a J.D. in 1991; practiced law in Chicago, IL; lecturer on constitutional law, University of Chicago; member, Illinois State Senate, 1997–2004; elected as a Democrat to the U.S. Senate in 2004; and served from January 3, 2005, to November 16, 2008, when he resigned from office, having been elected President; family: married to Michelle; two children: Malia and Sasha; elected as President of the United States on November 4, 2008, and took the oath of office on January 20, 2009. EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW., 20500 Eisenhower Executive Office Building (EEOB), 17th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue, NW., 20500, phone (202) 456–1414, http://www.whitehouse.gov The President of the United States.—Barack H. Obama. Personal Aide to the President.—Katherine Johnson. Special Assistant to the President and Personal Aide.—Reginald Love. OFFICE OF THE VICE PRESIDENT phone (202) 456–1414 The Vice President.—Joseph R. Biden, Jr. Chief of Staff to the Vice President.—Bruce Reed, EEOB, room 202, 456–9000. Deputy Chief of Staff to the Vice President.—Alan Hoffman, EEOB, room 202, 456–9000. Counsel to the Vice President.—Cynthia Hogan, EEOB, room 246, 456–3241. -

Congressional Record—House H3279

April 29, 2014 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — HOUSE H3279 lending programs, it would be difficult for not be there when you need it. We lost State Senate, I supported charters as them to object on budgetary grounds. millions in sales because Congress one of the best hopes to genuinely re- For every dollar put into Ex-Im, Che- dithered. form our school system. ney said, ‘‘there’s been a $20 return to Ladies and gentlemen, at the end of In Congress, those of us who support the U.S. economy.’’ the day, this is the most straight- charter schools should express that And again, the same speech, Vice forward imaginable proposition. This is support by ensuring that Federal pol- President Cheney said: about shoring up, strengthening, sup- icy encourages States to adopt expan- Ex-Im Bank is remarkably effective at porting the manufacturing sector of sive charter laws. helping create jobs, opportunities for trade, the American economy and creating Further, we need to ensure that stable democracies, and vibrant economies good-paying jobs. Washington does not put up bureau- throughout the world. The Bank has made a With that, Mr. Speaker, I yield back cratic roadblocks that would keep tremendous contribution as a rapid response, the balance of my time. State, city, and county governments service-oriented agency designed to meet the export financing needs of American busi- f from experimenting with new ideas and nesses. CURRENT EVENTS AFFECTING establishing effective charter school Indeed, the Bank has been reauthor- AMERICA programs. ized a number of times throughout its Mr. Speaker, I cannot say enough The SPEAKER pro tempore. -

And with Google Or Related Entities

What We Can Learn from Google’s Support for Hillary Clinton Google executives and employees bet heavily on a Clinton victory, hoping to extend the company’s influence on the Obama White House. They lost that bet, and are left scrambling to find an entrée to the Trump Administration. Google’s playbook with Clinton reveals how the company most likely will seek to influence the new administration. There already are signs of that influence: Joshua Wright, who co-wrote a Google-funded paper while on the faculty of George Mason University and currently works at Google’s main antitrust law firm, was named to the Trump transition team on competition issues. Alex Pollock, of the Google-funded R Street Institute, has also been named to oversee the transition at the FTC, which oversees Google's conduct. Introduction Google’s extraordinarily close relationship with President Obama’s administration led to a long list of policy victories of incalculable value to its business.1 An in-depth examination of the company’s efforts to extend that special relationship into the next administration, which it wrongly predicted would be led by Hillary Clinton, reveal what we might expect from Google for the incoming Trump administration. Google’s executives and employees employed a variety of strategies to elect Hillary Clinton and defeat Donald Trump. Google permeated Clinton’s sphere of influence on a broad scale, rivaling the influence it exerted over the Obama administration. A review found at least 57 people were affiliated with both Clinton—in her presidential campaign, in her State Department, at her family foundation—and with Google or related entities. -

Nejhe Urban Interventions N JOSEPH M

The NEW ENGLAND THE NEW JOURNAL ENGLAND OF HIGHERJOURNAL EDUCATION OF HIGHER EDUCATION Trends & Indicators in Higher Education 2009 COMMENTARY & ANALYSIS Thriving Through Recession n ROGER GOODMAN Many Sizes Fit All n EPHRAIM WEISSTEIN AND DAVID JACOBSON Needed in School Teaching: A Few Good Men SPRING 2009 VOLUME XXIII, NO. 5 n VALORA WASHINGTON www.nebhe.org/nejhe Urban Interventions n JOSEPH M. CRONIN New England’s State of College Readiness n ROXANNA P. MENSON, THANOS PATELIS AND ARTHUR DOYLE TWO VERMON T COLLEGES LOOK T O BOOS T ST UDEN T RE T EN T ION Creating a Retention Quilt n ALBERT DECICCIO, ANNE HOPKINS GROSS AND KAREN GROSS First-Generation, Low-Income Students n DONNA DALTON, CAROL A. MOORE AND ROBERT WHITTAKER FORUM Internationalization Campuses Abroad: Next Frontier or Bubble? n MADELEINE F. GREEN Reaching Beyond Elite International Students n PAUL LEBLANC Academic Culture Shock n KARA A. GODWIN MOUs: A Kyoto Protocol? n MICHAEL E. LESTZ Extra Step for Study Abroad n KERALA TAYLOR AND NICHOLAS FITZHUGH Water of Life n ANTHONY ZUENA COMMENTARY & ANALYSIS FROM THE NEW ENGLAND BOARD OF HIGHER EDUCATION Which Road Would You Choose? Possible Success Success Available (All Traffic MUST Exit) Next 4 Exits Exit 1 Exit 2 Exit 3 Exit 4 Exit 1 Four-Year Two-Year Professional More Four-Year College College College Training Destinations Graduating from a four-year college is an important goal, but should it be the only goal? The Nellie Mae Education Foundation is investigating this and other questions through our Pathways to Higher Learning initiative. -

Politics Indiana

Politics Indiana V14 N44 Tuesday, June 24, 2008 JLT labors under the unity facade UAW, Schellinger don’t join Jill’s Convention confab By RYAN NEES INDIANAPOLIS - Jill Long Thompson has work still to do with the party faithful, who at the state convention Saturday appeared more swept by the candidacy of Barack Obama and even the muted appearances by the Hoosier Congressional delegation than of Indiana’s first female gubernato- rial nominee. And behind the scenes, the machinery of the Democratic establishment still appears to be exacting upon her nothing short of malicious ven- geance. The candidate was met with polite ap- plause as she toured district and interest group caucus meetings, but skepticism persisted especially amongst the roughly half of the party that supported her opponent in Indiana’s May primary. That unease was punctuated dramatically by the UAW’s refusal to endorse her candidacy the morning of the conven- tion, a move that appeared designed to rain on the nominee’s parade. Jill Long Thompson listens to her brother talk about her life and candidacy The UAW’s support provided vital to archi- just prior to taking the stage Saturday at the Indiana Democratic Conven- tect Jim Schellinger’s primary tion. (HPI Photo by Brian A. Howey) campaign, which received See Page 4 Back home again with Jill By BRIAN A. HOWEY NASHVILLE, Ind. - In the Hoosier brand of guber- natorial politics, home is where the heart is. We remember Frank O’Bannon talking about his “wired” barn down near Corydon. In January 2005, Mitch Daniels talked about an “These days many politicians Amish-style barn raising. -

Panel of Journalists Explores Nation's Dramatic 2012 Election Campaign

Panel of Journalists Explores Nation’s Dramatic 2012 Election Campaign Panelists Mike Allen Chief White House Correspondent Politico Charlie Cook Editor and Publisher “The Cook Political Report” Chris Wallace Anchor “Fox News Sunday” Judy Woodruff Senior Correspondent “PBS News Hour” Moderator David Rubenstein President The Economic Club of Washington October 11, 2012 Excerpts from the Panel Discussion What Went Wrong for President Obama in the First Debate? Mr. Cook: “The President looked to me like a team that was vastly overconfident, that didn’t fear or respect his opponent and didn’t take it very seriously.” Ms. Woodruff: “I keep thinking of The New Yorker cartoon with Romney standing there and an empty chair….” Mr. Allen: “When you’re President, it’s been four years….since anybody has gotten in your grill.” Mr. Wallace: “I wasn’t a bit surprised that Romney did as well as he did. He did 23 debates in the Republican primaries that lasted 43 hours.” Will the Republicans Gain Control of the Senate? 1 Mr. Cook: “A year-and-a-half ago, I would have said a 60, 70 percent chance of Republicans taking a majority. Now I’d put it down maybe around 40 (percent).” Mr. Allen: “We think whoever gets the White House will get the Senate.” Mr. Wallace: “Right now, I think the conventional wisdom and the Charlie Cook wisdom is it’s probably less than 50-50 that the Republicans will take the Senate.” Can the Democrats Gain Control of the House? Mr. Cook: “It’s a real long shot.” Ms. -

Campaigning in 140 Characters (Or Less)

Campaigning in 140 Characters (or Less) How Twitter Changed Running for President By Joseph Vitale Spring 2016 Table of Contents Running for Office in the Internet Age………………………………….3 Mass Media and Elections: A Brief History…………………………….8 Politics and the Social Web…………………..………………………..10 Candidates Foray into Web 1.0………….……………..………………10 Candidates Move into Web 2.0………….……..………………………13 The Audacity to Tweet: Obama’s Digital Strategy……………….……15 2008: Obama Signs Up For Twitter…….……….……………………..17 2012: Obama and His ReElection………….…………………………26 Obama and a Changed Twitter……………….………………………..32 Entering the 2016 Election…………………….………………………34 Feeling the Bern: Viral Moments in Elections ….………………….…37 Trump’s Insults: Attacks on Twitter……………….………………..…38 Clinton’s Campaign: Questionable Choices……….………………….41 Analyzing Twitter’s Role…….…………………….………………….47 Twitter’s Future……………………………………….……………….49 References …………………………………………….………………51 Running for Office in the Internet Age In a presidential election, campaigns have one goal: To “put feet on the ground and bodies in the voting booth.” Elections are about doing this effectively and efficiently, and they rely on developed strategies that connect candidates with voters. These operations, which require dozens of staffers and strategists, aim to provide citizens with information about a candidate so that they will organize for and contribute to their campaigns. The goal, ultimately, is to encourage voters to choose their preferred candidate on election day. The prize, hopefully, is the candidate’s assumption of the Office of the President of the United States. Since the first presidential elections, communication has played a central role in campaigning. It is, as White House media advisor Bob Mead wrote, the “essence of a political campaign,” allowing a candidate to convey his ideas and visions to voters with the hope that they 1 can trust him, support him and elect him. -

I State Political Parties in American Politics

State Political Parties in American Politics: Innovation and Integration in the Party System by Rebecca S. Hatch Department of Political Science Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ John H. Aldrich, Supervisor ___________________________ Kerry L. Haynie ___________________________ Michael C. Munger ___________________________ David W. Rohde Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Political Science in the Graduate School of Duke University 2016 i v ABSTRACT State Political Parties in American Politics: Innovation and Integration in the Party System by Rebecca S. Hatch Department of Political Science Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ John H. Aldrich, Supervisor ___________________________ Kerry L. Haynie ___________________________ Michael C. Munger ___________________________ David W. Rohde An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Political Science in the Graduate School of Duke University 2016 Copyright by Rebecca S. Hatch 2016 Abstract What role do state party organizations play in twenty-first century American politics? What is the nature of the relationship between the state and national party organizations in contemporary elections? These questions frame the three studies presented in this dissertation. More specifically, I examine the organizational development -

Collective Action for Social Change

Collective Action for Social Change March 1, 2011 21:14 MAC-US/ACTION Page-i 9780230105379_01_prex March 1, 2011 21:14 MAC-US/ACTION Page-ii 9780230105379_01_prex Collective Action for Social Change An Introduction to Community Organizing Aaron Schutz and Marie G. Sandy March 1, 2011 21:14 MAC-US/ACTION Page-iii 9780230105379_01_prex collective action for social change Copyright © Aaron Schutz and Marie G. Sandy, 2011. All rights reserved. First published in 2011 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN® in the United States—a division of St. Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Where this book is distributed in the UK, Europe and the rest of the World, this is by Palgrave Macmillan, a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. ISBN: 978–0–230–10537–9 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Schutz, Aaron. Collective action for social change : an introduction to community organizing / Aaron Schutz and Marie G. Sandy. p. cm. ISBN–13: 978–0–230–10537–9 (hardback) ISBN–10: 0–230–10537–8 1. Community organization—United States. 2. Social change— United States. 3. Community organization—United States— Case studies. 4. Social change—United States—Case studies. I. Sandy, Marie G., 1968– II. Title. HN65.S4294 2011 361.8—dc22 2010041384 A catalogue record of the book is available from the British Library. -

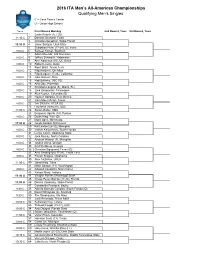

Finalbg Qual Sing DRAW2016

2016 ITA Men’s All-American Championships Qualifying Men's Singles C = Case Tennis Center U = Union High School Times First Round Monday 2nd Round, Tues 3rd Round, Tues 1 Justin Butsch (1), LSU 11:30 C 2 Dominic Bechard, Tulsa 3 Christian Seraphim, Wake Forest 10:30 U 4 Jaime Barajas, Utah State 5 Sebastian Heim (17-24), UC Irvine 8:00 C 6 Sameer Kumar, Stanford 7 Adam Moundir, Old Dominion 8:00 C 8 Jeffrey Schorsch, Valparaiso 9 Alec Adamson (10), UC Davis 8:00 C 10 Robert Levine, Duke 11 Ronit Bisht, Texas Tech 8:00 C 12 Filip Kraljevic, Ole Miss 13 Filip Bergevi (17-24), California 8:00 C 14 Jake Hansen, Rice 15 Rob Bellamy, USC (Q) 8:00 C 16 Alex Day, Princeton 17 Christian Langmo (5), Miami (FL) 8:00 C 18 Jack Schipanski, Tennessee 19 Alex Keyser, Columbia (Q) 8:00 C 20 Hayden Sabatka, New Mexico 21 John Mee (25-32), Texas 8:00 C 22 Joe DiGuilio, UCLA (Q) 23 Laurence Verboven, USC 11:00 C 24 Samm Butler, SMU 25 Benjamin Ugarte (14), Purdue 8:00 C 26 Dylan King, Yale (Q) 27 Matic Spec, Minnesota 11:30 U 28 Jacob Dunbar, Richmond 29 Kai Lemke (25-32), Memphis 8:00 C 30 Vadym Kalyuzhnyy, South Florida 31 Lucas Gerch, Oklahoma State 9:00 C 32 Jack Murray, North Carolina 33 Andrew Watson (3), Memphis 8:00 C 34 Jayson Amos, Oregon 35 Emil Reinberg, Georgia 9:00 C 36 Christian Sigsgaard, Texas (Q) 37 Alex Sendegeya (17-24), Texas Tech 9:00 C 38 Florian Bragusi, Oklahoma 39 Alex Cozbinov, UNLV 11:00 C 40 Jarod Hing, Tulsa 41 Mitch Stewart (11), Washington 9:00 C 42 Edward Covalschi, Notre Dame 43 Raheel Manji, Indiana 11:00 U 44 Vaughn Hunter,