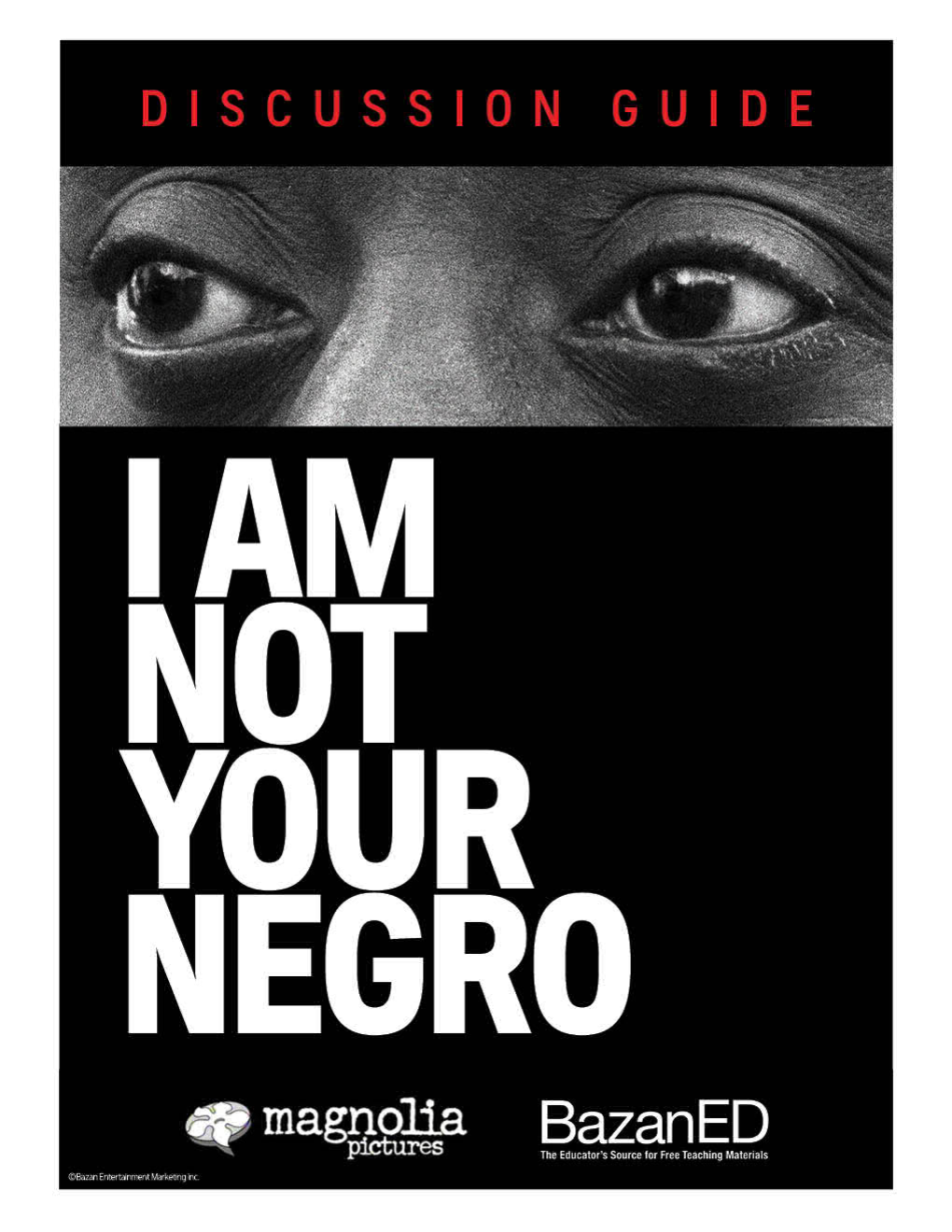

I Am Not Your Negro Discussion Guide About the Film

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“I Am Not Your Negro” (2016) Argument-Based Questions

“I Am Not Your Negro” (2016) Argument-Based Questions These argument-based questions accompany the 2016 documentary “I Am Not Your Negro,” which was created from a set of unpublished writings by James Baldwin. Baldwin was working on a book, one that he did not complete but for which he prepared extensive notes, taking a very autobiographical look at the divergent and convergent lives and deaths of three towing civil rights leaders: Martin Luther King, Jr., Medgar Evers, and Malcolm X. The documentary and these questions can be used as part of a unit on Civil Rights, African-American history, or simply American history. Students can be given these questions in advance of screening the film, for completion afterward. Or, the documentary can be paused at intervals so students can discuss or respond in writing to the questions. The timings attached to each question are approximately (not precisely) aligned with the film. It would be sufficient to screen the first half of this documentary – through the first 45 minutes – for classes with younger students, students sensitive to images of violence (there are several of these in the film’s second half), or students very unfamiliar with the history of the Civil Rights movement. There are various arguable angles into the civil rights era, and this documentary, as the questions below suggest. One overarching debatable issue is: James Baldwin establishes as one of his unifying arguments, in the writings on which “I Am Not Your Negro” is based and elsewhere, that America as a whole has been more damaged by racism than have African-Americans and other racial minorities, racism’s direct targets. -

Feature Films

FEATURE FILMS NEW BERLINALE 2016 GENERATION CANNES 2016 OFFICIAL SELECTION MISS IMPOSSIBLE SPECIAL MENTION CHOUF by Karim Dridi SPECIAL SCREENING by Emilie Deleuze TIFF KIDS 2016 With: Sofian Khammes, Foued Nabba, Oussama Abdul Aal With: Léna Magnien, Patricia Mazuy, Philippe Duquesne, Catherine Hiegel, Alex Lutz Chouf: It means “look” in Arabic but it is also the name of the watchmen in the drug cartels of Marseille. Sofiane is 20. A brilliant Some would say Aurore lives a boring life. But when you are a 13 year- student, he comes back to spend his holiday in the Marseille ghetto old girl, and just like her have an uncompromising way of looking where he was born. His brother, a dealer, gets shot before his eyes. at boys, school, family or friends, life takes on the appearance of a Sofiane gives up on his studies and gets involved in the drug network, merry psychodrama. Especially with a new French teacher, the threat ready to avenge him. He quickly rises to the top and becomes the of being sent to boarding school, repeatedly falling in love and the boss’s right hand. Trapped by the system, Sofiane is dragged into a crazy idea of going on stage with a band... spiral of violence... AGAT FILMS & CIE / FRANCE / 90’ / HD / 2016 TESSALIT PRODUCTIONS - MIRAK FILMS / FRANCE / 106’ / HD / 2016 VENICE FILM FESTIVAL 2016 - LOCARNO 2016 HOME by Fien Troch ORIZZONTI - BEST DIRECTOR AWARD THE FALSE SECRETS OFFICIAL SELECTION TIFF PLATFORM 2016 by Luc Bondy With: Sebastian Van Dun, Mistral Guidotti, Loic Batog, Lena Sukjkerbuijk, Karlijn Sileghem With: Isabelle Huppert, Louis Garrel, Bulle Ogier, Yves Jacques Dorante, a penniless young man, takes on the position of steward at 17-year-old Kevin, sentenced for violent behavior, is just let out the house of Araminte, an attractive widow whom he secretly loves. -

James Baldwin As a Writer of Short Fiction: an Evaluation

JAMES BALDWIN AS A WRITER OF SHORT FICTION: AN EVALUATION dayton G. Holloway A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 1975 618208 ii Abstract Well known as a brilliant essayist and gifted novelist, James Baldwin has received little critical attention as short story writer. This dissertation analyzes his short fiction, concentrating on character, theme and technique, with some attention to biographical parallels. The first three chapters establish a background for the analysis and criticism sections. Chapter 1 provides a biographi cal sketch and places each story in relation to Baldwin's novels, plays and essays. Chapter 2 summarizes the author's theory of fiction and presents his image of the creative writer. Chapter 3 surveys critical opinions to determine Baldwin's reputation as an artist. The survey concludes that the author is a superior essayist, but is uneven as a creator of imaginative literature. Critics, in general, have not judged Baldwin's fiction by his own aesthetic criteria. The next three chapters provide a close thematic analysis of Baldwin's short stories. Chapter 4 discusses "The Rockpile," "The Outing," "Roy's Wound," and "The Death of the Prophet," a Bi 1 dungsroman about the tension and ambivalence between a black minister-father and his sons. In contrast, Chapter 5 treats the theme of affection between white fathers and sons and their ambivalence toward social outcasts—the white homosexual and black demonstrator—in "The Man Child" and "Going to Meet the Man." Chapter 6 explores the theme of escape from the black community and the conseauences of estrangement and identity crises in "Previous Condition," "Sonny's Blues," "Come Out the Wilderness" and "This Morning, This Evening, So Soon." The last chapter attempts to apply Baldwin's aesthetic principles to his short fiction. -

Black Women, Educational Philosophies, and Community Service, 1865-1965/ Stephanie Y

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2003 Living legacies : Black women, educational philosophies, and community service, 1865-1965/ Stephanie Y. Evans University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Evans, Stephanie Y., "Living legacies : Black women, educational philosophies, and community service, 1865-1965/" (2003). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 915. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/915 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. M UMASS. DATE DUE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST LIVING LEGACIES: BLACK WOMEN, EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOPHIES, AND COMMUNITY SERVICE, 1865-1965 A Dissertation Presented by STEPHANIE YVETTE EVANS Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2003 Afro-American Studies © Copyright by Stephanie Yvette Evans 2003 All Rights Reserved BLACK WOMEN, EDUCATIONAL PHILOSOHIES, AND COMMUNITY SERVICE, 1865-1964 A Dissertation Presented by STEPHANIE YVETTE EVANS Approved as to style and content by: Jo Bracey Jr., Chair William Strickland, -

The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1

Contents Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances .......... 2 February 7–March 20 Vivien Leigh 100th ......................................... 4 30th Anniversary! 60th Anniversary! Burt Lancaster, Part 1 ...................................... 5 In time for Valentine's Day, and continuing into March, 70mm Print! JOURNEY TO ITALY [Viaggio In Italia] Play Ball! Hollywood and the AFI Silver offers a selection of great movie romances from STARMAN Fri, Feb 21, 7:15; Sat, Feb 22, 1:00; Wed, Feb 26, 9:15 across the decades, from 1930s screwball comedy to Fri, Mar 7, 9:45; Wed, Mar 12, 9:15 British couple Ingrid Bergman and George Sanders see their American Pastime ........................................... 8 the quirky rom-coms of today. This year’s lineup is bigger Jeff Bridges earned a Best Actor Oscar nomination for his portrayal of an Courtesy of RKO Pictures strained marriage come undone on a trip to Naples to dispose Action! The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1 .......... 10 than ever, including a trio of screwball comedies from alien from outer space who adopts the human form of Karen Allen’s recently of Sanders’ deceased uncle’s estate. But after threatening each Courtesy of Hollywood Pictures the magical movie year of 1939, celebrating their 75th Raoul Peck Retrospective ............................... 12 deceased husband in this beguiling, romantic sci-fi from genre innovator John other with divorce and separating for most of the trip, the two anniversaries this year. Carpenter. His starship shot down by U.S. air defenses over Wisconsin, are surprised to find their union rekindled and their spirits moved Festival of New Spanish Cinema .................... -

Grice, Karly Marie

“Wake Up, America!”: The March Trilogy as “Wake Work” “If we do not now dare everything, the fulfillment of that prophecy, recreated from the Bible in song by a slave, is upon us: God gave Noah the rainbow sign, No more water, the fire next time!” -James Baldwin John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and Nate Powell’s March trilogy has received numerous accolades as a primer of history and nonviolence. While these roles are important, I argue that the books perform another important role for contemporary society. In my presentation, I assert the visual narrative structure of the March trilogy embodies the complexity of what Christina Sharpe describes as “the wake” where “to be in the wake is to occupy and to be occupied by the continuous and changing present of slavery’s as yet unresolved unfolding” (13-14). Sharpe’s explanation of “the wake” is Derridean in nature: “the wake” is made up of multiple, contextual understandings of “wake”: rough waters, the aftermath of turmoil, a mourning period, to awaken, and to be aware. By engaging with texts that display the black diasporic experience, Sharpe explains that readers can perform “wake work,” which she describes as “a mode of inhabiting and rupturing this episteme with our known lived and un/imaginable lives” (18). The March trilogy1 facilitates wake work through innovation in style, composition, and comics. While this engagement occurs in many ways, the scope of my presentation focuses specifically on how narrative time is visually disrupted in the March trilogy. Namely, the untidy oscillation between Lewis’s Civil Rights Movement past and the narrative present of President Obama’s inauguration creates disruptions where the past and present invade one another’s visual space. -

Directors Fortnight Cannes 2000 Winner Best Feature

DIRECTORS WINNER FORTNIGHT BEST FEATURE CANNES PAN-AFRICAN FILM 2000 FESTIVAL L.A. A FILM BY RAOUL PECK A ZEITGEIST FILMS RELEASE JACQUES BIDOU presents A FILM BY RAOUL PECK Patrice Lumumba Eriq Ebouaney Joseph Mobutu Alex Descas Maurice Mpolo Théophile Moussa Sowié Joseph Kasa Vubu Maka Kotto Godefroid Munungo Dieudonné Kabongo Moïse Tshombe Pascal Nzonzi Walter J. Ganshof Van der Meersch André Debaar Joseph Okito Cheik Doukouré Thomas Kanza Oumar Diop Makena Pauline Lumumba Mariam Kaba General Emile Janssens Rudi Delhem Director Raoul Peck Screenplay Raoul Peck Pascal Bonitzer Music Jean-Claude Petit Executive Producer Jacques Bidou Production Manager Patrick Meunier Marianne Dumoulin Director of Photography Bernard Lutic 1st Assistant Director Jacques Cluzard Casting Sylvie Brocheré Artistic Director Denis Renault Art DIrector André Fonsny Costumes Charlotte David Editor Jacques Comets Sound Mixer Jean-Pierre Laforce Filmed in Zimbabwe, Mozambique and Belgium A French/Belgian/Haitian/German co-production, 2000 In French with English subtitles 35mm • Color • Dolby Stereo SRD • 1:1.85 • 3144 meters Running time: 115 mins A ZEITGEIST FILMS RELEASE 247 CENTRE ST • 2ND FL • NEW YORK • NY 10013 www.zeitgeistfilm.com • [email protected] (212) 274-1989 • FAX (212) 274-1644 At the Berlin Conference of 1885, Europe divided up the African continent. The Congo became the personal property of King Leopold II of Belgium. On June 30, 1960, a young self-taught nationalist, Patrice Lumumba, became, at age 36, the first head of government of the new independent state. He would last two months in office. This is a true story. SYNOPSIS LUMUMBA is a gripping political thriller which tells the story of the legendary African leader Patrice Emery Lumumba. -

2017 Highlights

EIGHTH ANNUAL EDITION November 9-16, 2017 “DOC NYC has quickly become one of the city’s grandest film events.” Spans downtown Hailed as Manhattan from “ambitious” IFC Center to 250+ SVA Theatre and films & events “selective but Cinepolis Chelsea eclectic” ARTISTIC DIRECTOR EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Thom Powers programs for the Toronto Raphaela Neihausen & Powers run the weekly International Film Festival and hosts the series Stranger Than Fiction at IFC Center and podcast Pure Nonfiction. host WNYC’s “Documentary of the Week.” DOC NYC has welcomed over 50 sponsors through the years, most of which have returned for 3+ years. ACSIL Discovery Image Nation Abu Dhabi Participant Media Technicolor-Postworks NY Brooklyn Roasting Co. Docurama Impact Partners Peru Ministry of Tribeca Grand Hotel Tourism & Culture Chicago Media Project Essentia Water IndieWire VH1 & Logo Documentary Posteritati Films Chicken & Egg Pictures Goose Island JustFilms/Ford Foundation RADiUS Vulcan Cowan DeBaets Half Pops Abrahams & Sheppard Kickstarter The Screening Room Wheelhouse Creative Heineken CNN Films MTV Stoli The World Channel International City of New York Documentary Association NBCUniversal Archives SundanceNow The Yard Mayor’s Office for Doc Club Media & Entertainment Illy New York Magazine ZICO SVA Owl’s Brew DOCNYC.NET DOCNYCFEST Voted by Movie Maker Magazine as one of the top 5 coolest documentary film festivals in the world! DOC NYC 2016 FEATURED: 12k 200+ likes on Facebook 60k special guests visits DOCNYC.net 125k 92 reached by e-mail Largest premieres Documentary -

Race and Social Justice in America

Race and Social Justice in America This list of titles available at Pasadena Public Library is compiled from suggestions from The New York Times and other publications, other public libraries, and Pasadena Public Library staff recommendations. BOOKS FOR ADULTS The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness Michelle Alexander ©2011 Despite the triumphant dismantling of the Jim Crow Laws, the system that once forced African Americans into a segregated second-class citizenship still haunts America, the US criminal justice system still unfairly targets black men and an entire segment of the population is deprived of their basic rights. Outside of prisons, a web of laws and regulations discriminates against these wrongly convicted ex-offenders in voting, housing, employment and education. Alexander here offers an urgent call for justice. 364.973 ALE I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings Maya Angelou © 1969 [T]his memoir traces Maya Angelou's childhood in a small, rural community during the 1930s. Filled with images and recollections that point to the dignity and courage of black men and women, Angelou paints a sometimes disquieting, but always affecting picture of the people-and the times-that touched her life. 92 ANGELOU,M The Fire Next Time James Baldwin ©1963 The Fire Next Time contains two essays by James Baldwin. Both essays address racial tensions in America, the role of religion as both an oppressive force and an instrument for inspiring rage, and the necessity of embracing change and evolving past our limited ways of thinking about race. 305.896 BAL I Am Not Your Negro [Documentary DVD] Written by James Baldwin ©2017 Using James Baldwin's unfinished final manuscript, Remember This House, this documentary follows the lives and successive assassinations of three of the author's friends, Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr., delving into the legacy of these iconic figures and narrating historic events using Baldwin's original words and a flood of rich archival material. -

Film Suggestions to Celebrate Black History

Aurora Film Circuit I do apologize that I do not have any Canadian Films listed but also wanted to provide a list of films selected by the National Film Board that portray the multi-layered lives of Canada’s diverse Black communities. Explore the NFB’s collection of films by distinguished Black filmmakers, creators, and allies. (Link below) Black Communities in Canada: A Rich History - NFB Film Info – data gathered from TIFF or IMBd AFC Input – Personal review of the film (Nelia Pacheco Chair/Programmer, AFC) Synopsis – this info was gathered from different sources such as; TIFF, IMBd, Film Reviews etc. FILM TITEL and INFO AFC Input SYNOPSIS FILM SUGGESTIONS TO CELEBRATE BLACK HISTORY MONTH SMALL AXE I am very biased towards the Director Small Axe is based on the real-life experiences of London's West Director: Steve McQueen Steve McQueen, his films are very Indian community and is set between 1969 and 1982 UK, 2020 personal and gorgeous to watch. I 1st – MANGROVE 2hr 7min: English cannot recommend this series Mangrove tells this true story of The Mangrove Nine, who 5 Part Series: ENOUGH, it was fantastic and the clashed with London police in 1970. The trial that followed was stories are a must see. After listening to the first judicial acknowledgment of behaviour motivated by Principal Cast: Gary Beadle, John Boyega, interviews/discussions with Steve racial hatred within the Metropolitan Police Sheyi Cole Kenyah Sandy, Amarah-Jae St. McQueen about this project you see his 2nd – LOVERS ROCK 1hr 10 min: Aubyn and many more.., A single evening at a house party in 1980s West London sets the passion and what this production meant to him, it is a series of “love letters” to his scene, developing intertwined relationships against a Category: TV Mini background of violence, romance and music. -

Un Film De / a Film by Raoul Peck Une Coproduction / a Coproduction : Velvet Film, ARTE France (France / Haïti, 2009, 105Mn, D-Cinéma)

Un film de / A film by Raoul PECK Une coproduction / A coproduction : Velvet Film, ARTE France (France / Haïti, 2009, 105mn, D-cinéma) Un film de / A film by Raoul PECK Moloch Tropical raconte les dernières In a fortress perched on the top of a mountain, vingt-quatre heures d’un pouvoir avant sa chute. a democratically elected « President » and his Dans le huis clos d’un palais-forteresse niché closest collaborators are getting ready for a state au sommet d’une montagne, le « président » celebration. Foreign chiefs of state and dignitaries élu démocratiquement entouré de ses proches of all sorts are expected. But in the morning of the collaborateurs, se prépare pour une soirée de gala event, he wakes up to find the country inflamed commémoratif, où seront présents dignitaires et the streets in turmoil. As the day goes on, rebellion chefs d’États étrangers. Mais ce jour-là dans la worsens. Meanwhile, expected guests are ville, des barricades s’élèvent. Et c’est là que les withdrawing from the party one after another… choses vont déraper… RAOUL PECK / RÉALISATEUR, SCÉNARISTE, proDUCTEUR / DIRECTOR, SCREENWRITER AND ProDUCER. Né à Port-au-Prince, Haïti // Born in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Ministre de la Culture et de la Communication de la République d’Haïti (1996 - 1997) // Minister of Culture and Communication of the Haitian Republic (1996 - 1997). Récipiendaire du Prix Irene Diamond pour l’ensemble de son travail en faveur des Droits Humains, 2001, Human Rights Watch // Honoured by the Irene Diamond Prize for his entire work in favour of human rights, 2001, Human Rights Watch. -

Spring Semester Catalog • 2020

Rethink Learning Discovery Vitality Camaraderie Enrichment Creativity SPRING SEMESTER CATALOG • 2020 MONDAY, MARCH 2–FRIDAY, JUNE 5, 2020 CONTENTS 3 From the Director 4 Virtual/Hybrid Study Groups At-A-Glance 5 Virtual/Hybrid Study Group Descriptions 6 Chicago Study Groups At-A-Glance 8 Chicago Study Group Descriptions 35 The 1619 Project 36 Evanston Study Groups At-A-Glance 38 Evanston Study Group Descriptions 52 Membership Options 54 At-A-Glance Availability of Membership Types 55 Registration & Refund Policies 57 Registration Form 59 Campus Maps 61 Resources 62 Calendar KEY TO SYMBOLS IN CATALOG Technology use (including but not limited Field trips — walking to email, Internet research, use of Canvas, opening Word and PDF documents) Field trips — own transportation needed Kindle edition available Will read 20+ pages a week Class member’s participation as a discussion Will read 40+ pages a week leader is strongly encouraged Digital SLR camera required Low level of discussion during class Movie group or films will be shown Medium level of discussion during class High level of discussion during class Contents 2 sps.northwestern.edu/olli FROM THE DIRECTOR, KIRSTY MONTGOMERY I am delighted to present Osher Lifelong Learning REGISTRATION HELP SESSIONS Institute’s (OLLI) spring semester, 2020. This eclectic If you will need help registering plan to attend one selection of studies will run for fourteen weeks, of our registration help sessions. New and existing from Monday, March 2, through Friday, June 5, 2020. members may stop by one of these sessions to Spring registration begins at 9 a.m. on Monday, get personal assistance registering using our January 27, 2020.