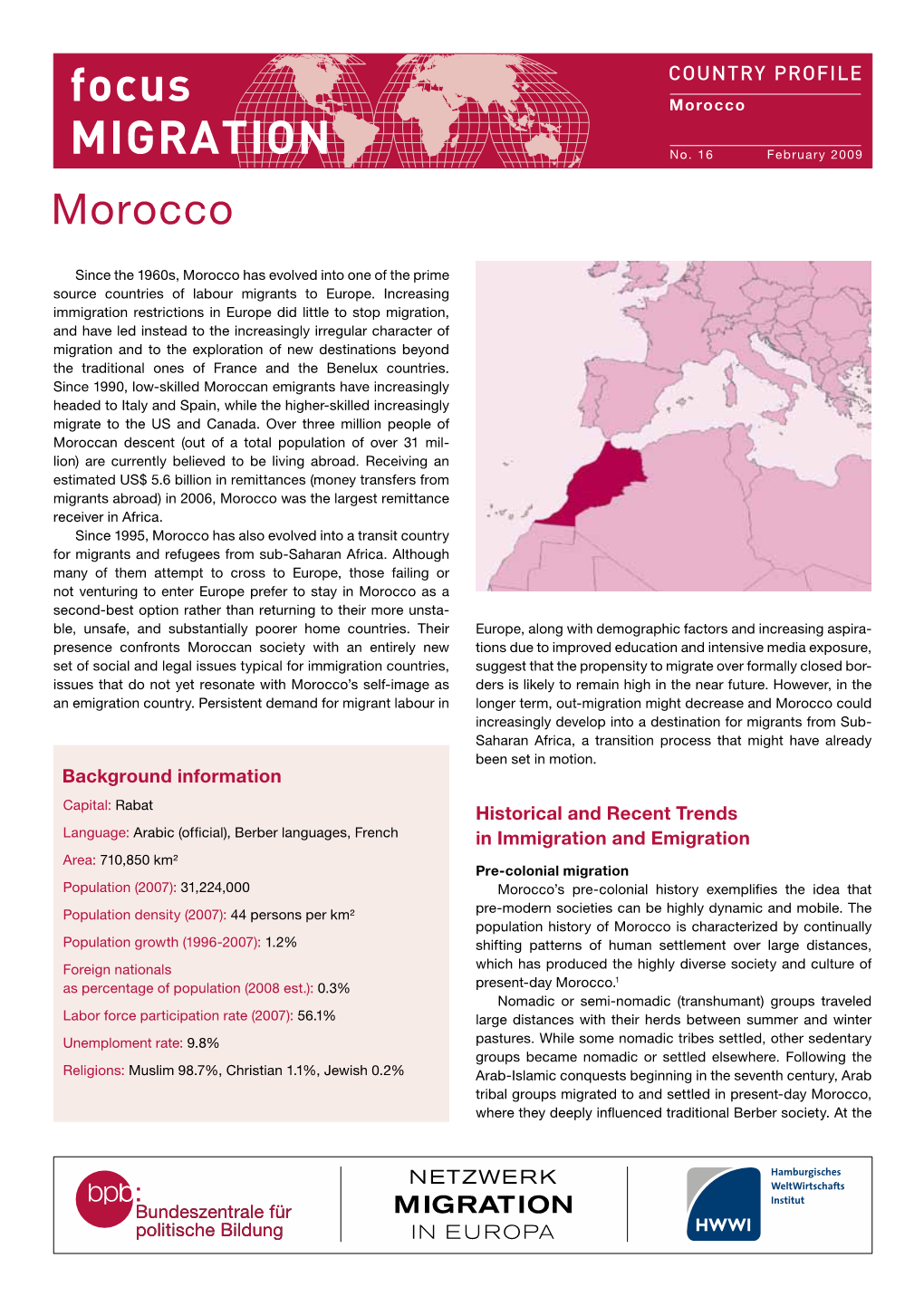

2009-Focus-Migration-Country-Profile-Morocco.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moroccan Diaspora in France: Community Building on Yabiladi Portal

ISSN: 2347-7474 International Journal Advances in Social Science and Humanities Available online at: www.ijassh.com RESEARCH ARTICLE Moroccan Diaspora in France: Community Building on Yabiladi Portal Tarik Samak Abstract Over the last decade, social networking sites emerge as an ideal tool of communication that facilitate interaction among people online. At the same time, in a world which is characterized by massive waves of migration, globalization results in the construction of the diaspora who seek through new ways to build communities. Within this framework, while traditional media have empowered diaspora members to maintain ties and bonds with their homeland and fellow members, the emergence of social media have offered new opportunities for diasporas to get involved in diasporic identity and community construction. The creation of several diasporic groups on social media like Yabiladi.com and WAFIN.be, respectively in France and Belguim, emphasize the vital role they play in everyday lives of the diaspora. To study the importance and implications of these online communities for diaspora members and investigate their online practices, this article carries out a virtual ethnography of the Moroccan community on Yabiladi portal in France. By means of the qualitative approach of interviews, this article aims at justifying whether the online groups of diasporic diasporic Moroccans in France can be defined as communities, and whether social networking sites can be considered as an alternative landscape for the diaspora to create links with other diasporic members. This article, through users’ experience, provides deep understanding of Yabiladi members’ beliefs about the ‘‘community’’ and their online daily practices which enable them to ‘‘imagine’’ it as a community. -

The State of the Art on Moroccan Emigration to Europe

The State of the Art on Moroccan Emigration to Europe LITERATURE REVIEW By Lalla Amina Drhimeur ERC AdG PRIME Youth Researcher, European Institute İstanbul Bilgi University PhD candidate in political science, Hassan II School of Law, Mohammedia, Casablanca, Morocco May 12, 2020 DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.3822021 ERC AdG PRIME Youth ISLAM-OPHOB-ISM 785934 Preface This literature review, prepared by Lalla Amina Drhimeur, is a state of the art on Moroccan emigration to Europe. It explores the history of Moroccan emigration to Europe with a focus on Belgium, France, Germany, and the Netherlands, which are the countries studied in the scope of the “PRIME Youth” project. This review also seeks to understand the recruitment processes deployed by receiving countries, as well as the regulations, and integration experiences that took place between the early 20th century and the 1960s. In doing so, it illustrates that Moroccan emigration is diverse and flexible in the way it adjusts to changing immigration policies, changes in the job market in the host countries but also to political, economic and social changes in Morocco. This literature review was prepared in the scope of the ongoing EU-funded research for the “PRIME Youth” project conducted under the supervision of the Principal Investigator, Prof. Dr. Ayhan Kaya, and funded by the European Research Council with the Agreement Number 785934. AYHAN KAYA Principal Investigator, ERC AdG PRIME Youth Research Jean Monnet Chair of European Politics of Interculturalism Director, European Institute İstanbul Bilgi University 2 The State of the Art on Moroccan Emigration to Europe Lalla Amina Drhimeur Introduction This state of the art on Moroccan emigration to Europe seeks to explore the history of Moroccan emigration to Europe with a focus on Belgium, France, Germany, and the Netherlands. -

Le Transnationalisme: Espace, Temps, Politique

Le Transnationalisme : Espace, Temps, Politique Thomas Lacroix To cite this version: Thomas Lacroix. Le Transnationalisme : Espace, Temps, Politique. Géographie. Université de Paris Est, 2018. tel-01810672 HAL Id: tel-01810672 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01810672 Submitted on 8 Jun 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Le Transnationalisme : Espace, Temps, Politique Thomas Lacroix, chargé de recherche CNRS Migrinter, Université de Poitiers Mémoire d’Habilitation à Diriger des Recherches Volume 1 : Position et projet scientifique Photo : Daniel Purroy Jury : Olivier Clochard, Chargé de Recherche CNRS, Migrinter, Université de Poitiers Janine Dahinden, Professeure d’études transnationales, CAPS, Université de Neuchâtel Géraud Magrin, Professeur de géographie, PRODIG, Université de Paris 1-Sorbonne Jean-Baptiste Meyer, Directeur de Recherche IRD, LPED, Université d’Aix Marseille Élise Massicard, Directrice de Recherche CNRS, CERI, Sciences Po Paris Swanie Potot, Chargée de Recherche CNRS, URMIS, Université de Nice Serge Weber, Professeur de géographie, ACP, Université de Paris Est Catherine Wihtol de Wenden, Directrice de Recherche CNRS, CERI, Sciences Po Soutenue à l’Université Paris Est, le 4 Mai 2018 À mes parents. 2 Remerciements Les remerciements écrits pour une habilitation à diriger des recherches prennent une teneur particulière. -

Les Cahiers Du Musée Berbère

Fondation Jardin Majorelle LES CAHIERS DU MUSÉE BERBÈRE CAHIER DU MUSÉE BERBÈRE III 2017 English version EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Editor: Björn Dahlström English translations: Helen Ranger & José Abeté BERBER MUSEUM Scientific Steering Committee Pierre Bergé Chairman of the Fondation Jardin Majorelle Madison Cox Deputy chairman of the Fondation Jardin Majorelle Björn Dahlström Curator of the Musée Berbère, Jardin Majorelle El Mehdi Iâzzi Professor, Ibn Zohr University, Agadir Driss Khrouz Former Director of the Library of the Kingdom of Morocco, Rabat Salima Naji Architect and Anthropologist, Rabat Ahmed Skounti Researcher and teacher, INSAP, Rabat and professor, Cadi Ayyad University, Marrakech CREDITS Figs I, II, III : Collection Musée Berbère, Fondation Jardin Majorelle, Marrakech Text and map : © Fondation Jardin Majorelle CONTENTS Foreword 5 Björn Dahlström Moroccan Immigration to France 6 Lahoussine Selouani Bibliography Overview Of Moroccan Jewish Migration: Internal Migration & Departures from Internal Migrations to Departures from Morocco 25 Yann Scioldo-Zürcher Bibliography Tinghir Jerusalem: Echoes from the Mellah 41 Kamal Hachkar THE KINGDOM OF MOROCCO Tanger N Tétouan RIF Nador Ouezzane Oujda O E Taounate Meknès Rabat Fès S Casablanca Aîn Leuh Khénifra ATLAS Beni Mellal MOYEN Marrakech TAFILALT Essaouira Rissani ATLAS TODRHA Telouet Oukaimeden DADÉS Taraudant HAUT Ouarzazate Agadir SIROUA Taznakht SOUSS DRAA Zagora Massa Foum Zguid Tamgrout Tahala Tagmout Tiznit ANTI-ATLASTata BANI Tafraout Akka A R A A H É S R P Guelmim Tan-Tan Laâyoune SAHARA LÉGENDE RIF montagne TODRHA région géographique et historique Dakhla Zagora ville, localité, lieu dit. 0 50 100 150 200 km Laguira 5 FOREWORD he Imazighen (plural of Amazigh) or Moroccan Berbers have been immigrating to Europe for a long Ttime, particularly to France. -

Bulletin Insert

August Arabic-speaking 25 Moroccans in France oroccan Arabs living in France Mhave lives that are very different from the ones they had in Morocco. There is greater freedom for women to leave the home and even work outside of the home. Since they have been exposed to western culture on a grand scale, their traditional culture and way of life have undergone many changes. Political unity has always been a dream among Arabs, but to- day the greatest tie among them is still the Arabic language. Ministry Obstacles Most Moroccan Arabs feel that ac- cepting Christ would deny their Ara- bic identity. To be a Moroccan Arab means to be a Muslim. Therefore, ��moh-RAH-kuhns they find it hard to conceive of being POPULATION: 443,000 anything other than Muslim. They LANGUAGE: Arabic, Moroccan Spoken need to understand that Jesus Christ RELIGION: Islam died to save people from every na- BIBLE: New Testament tion, including theirs. STATUS: Unreached Outreach Ideas the Holy Spirit to share the love of Believers in France need to befriend Christ with Moroccan Arabs in their Muslim neighbors, shower them France. Pray for God to strengthen, with hospitality, invite Muslim family encourage and protect the small members into their homes and love number of Arabs who have decided them in the name of Christ. to follow Jesus in France. Pray that France would be the incubator for a Prayer Focus Disciple Making Movement that will Pray for the Lord to call people led by spread to Morocco and beyond. SCRIPTURE Look at the proud! They trust in themselves, and their lives are crooked. -

Moroccan Diaspora in France: Community Building on Yabiladi Portal

Journal of Identity and Migration Studies Volume 10, number 2, 2016 Moroccan Diaspora in France: Community Building on Yabiladi Portal Tarik SAMAK Abstract. Over the last decade, social networking sites emerge as an ideal tool of communication that facilitates interaction among people online. At the same time, in a world that is characterized by massive waves of migration, globalization results in the construction of the Diaspora who seek through new ways to build communities. Within this framework, while traditional media have empowered diaspora members to maintain ties and bonds with their homeland and fellow members, the emergence of social media have offered new opportunities for diasporas to get involved in diasporas identity and community construction. The creation of several diasporas groups on social media like Yabiladi.com and WAFIN.be, respectively in France and Belguim, emphasize the vital role they play in everyday lives of the Diaspora. To study the importance and implications of these online communities for Diaspora members and investigate their online practices, this article carries out a virtual ethnography of the Moroccan community on Yabiladi portal in France. By means of the qualitative approach of interviews, this article aims at justifying whether the online groups of diasporas Moroccans in France can be defined as communities, and whether social networking sites can be considered as an alternative landscape for the Diaspora to create links with other diasporas members. This article, through users’ experience, provides deep understanding of Yabiladi members’ beliefs about the ‘‘community’’ and their online daily practices which enable them to ‘‘imagine’’ it as a community. Keywords: Moroccan Diaspora, community, social networking sites, Internet, ethnography Introduction In general terms, migration is not a new practice for humanity, nor is the investigation of migration a new area of research for academic studies. -

Redalyc.North African Migration Systems

Migración y Desarrollo ISSN: 1870-7599 [email protected] Red Internacional de Migración y Desarrollo México Haas, Hein de North african migration systems: evolution, transformations and development linkages Migración y Desarrollo, núm. 7, segundo semestre, 2006, pp. 65-95 Red Internacional de Migración y Desarrollo Zacatecas, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=66000704 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative RAÚL DELGADO WISE AND HUMBERTO MÁRQUEZ COVARRUBIAS NORTH AFRICAN MIGRATION SYSTEMS NORTH AFRICAN MIGRATION SYSTEMS: EVOLUTION, TRANSFORMATIONS AND DEVELOPMENT LINKAGES HEIN DE HAAS* ABSTRACT . The paper first analyses how the evolution and transformation of North African migration systems has been an integral part of more general processes of political and economic change. Subsequently, the extent to which policies can enhance the development impact of migration is assessed by analysing the case of Morocco, the region’s leading emigration coun� try. Over 3 million people of Moroccan descent (out of 30 million Moroccans) live abroad, mainly in Europe. Since the 1960s, the Moroccan state has stimulated migration for economic and political reasons, while simultaneously trying to maintain a tight control on «its» emi� grants. However, fearing remittance decline, a remarkable shift occurred after 1989. Along with policies to facilitate holiday visits and remittances, the Moroccan state adopted positive attitudes towards migrants’ transnational civic activism, integration and double citizenship. Huge increases in remittances (well over $5 billion in 2006) and holiday visits suggest that these policies have been partially successful. -

Moroccans in France: Their Organizations and Activities Back Home Thomas Lacroix, Antoine Dumont

Moroccans in France: their organizations and activities back home Thomas Lacroix, Antoine Dumont To cite this version: Thomas Lacroix, Antoine Dumont. Moroccans in France: their organizations and activities back home. 2012. halshs-00820391 HAL Id: halshs-00820391 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00820391 Preprint submitted on 4 May 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - ShareAlike| 4.0 International License Thomas Lacroix CNRS Research Fellow Migrinter, University of Poitiers Antoine Dumont Research Associate, Migrinter, University of Poitiers Moroccan in France: their organizations and activities back home Introduction The Moroccan is one of the largest migration groups in France, whose presence in France dates back from the early 20th century (De Haas 2005). In contrast with other North African states, Morocco has made emigration a key tool of its development policy. Against this backdrop, Moroccan authorities have maintained a continuous and often confrontational dialogue with Moroccan organizations abroad (Iskander 2010). Since the sixties, they played a key role in representing the overseas diaspora. But far from being a mere transmission belt of state policies, the Moroccan organizational field has generated a large array of political, cultural and social connections. -

Retirement Home? Ageing Migrant Workers in France and the Question

IMISCOE Research Series Alistair Hunter Retirement Home? Ageing Migrant Workers in France and the Question of Return IMISCOE Research Series This series is the official book series of IMISCOE, the largest network of excellence on migration and diversity in the world. It comprises publications which present empirical and theoretical research on different aspects of international migration. The authors are all specialists, and the publications a rich source of information for researchers and others involved in international migration studies. The series is published under the editorial supervision of the IMISCOE Editorial Committee which includes leading scholars from all over Europe. The series, which contains more than eighty titles already, is internationally peer reviewed which ensures that the book published in this series continue to present excellent academic standards and scholarly quality. Most of the books are available open access. For information on how to submit a book proposal, please visit: http://www. imiscoe.org/publications/how-to-submit-a-book-proposal. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/13502 Alistair Hunter Retirement Home? Ageing Migrant Workers in France and the Question of Return Alistair Hunter University of Edinburgh Edinburgh, UK ISSN 2364-4087 ISSN 2364-4095 (electronic) IMISCOE Research Series ISBN 978-3-319-64975-7 ISBN 978-3-319-64976-4 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-64976-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017952369 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2018. This book is an open access publication. Open access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any non commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. -

Being Moroccan’ Today: Dilemmas of Identity Related to the Origin of Moroccan Migrants in Europe

Ethnologia Polona 2015 (2016), 36, s. 121-136 Ethnologia Polona, vol. 36: 2015 (2016), 121 – 136 PL ISSN 0137 - 4079 ‘BEING MOROCCAN’ TODAY: DILEMMAS OF IDENTITY RELATED TO THE ORIGIN OF MOROCCAN MIGRANTS IN EUROPE RADOSŁAW STRYJEWSKI INSTITUTE OF ETHNOLOGY AND CULTURAL ANTHROPOLOGY THE UNIVERSITY OF WARSAW Researchers on Muslim migrants’ presence in Europe are mainly interested in following their integra- tion paths in their new countries, and, to a lesser extent, their dilemmas linked to the specificity of their countries of origin. In this article the focus is on the influence of ethnicity, understood in terms of categories inherent in the sending context, on the dilemmas of identity of Moroccan interviewees in Granada and Paris. * * * Badania nad obecnością imigrantów muzułmańskich w Europie często koncentrują się na ścieżkach integracji w nowych krajach z uwzględnieniem ich specyfiki, w mniejszym zaś stopniu na kontekstach warunkujących tożsamościowe wybory badanych, które odnoszą się do specyfiki ich kraju pochodzenia. W niniejszym artykule analizuję wpływ etniczności rozumianej w kategoriach wyniesionych z kraju pocho- dzenia na tożsamościowe rozterki moich marokańskich rozmówców w Paryżu i Granadzie. K e y w o r d s: Moroccans, ethnicity, regionalisms, migration The reflections presented in this article were provided by research conducted between 2006 and 2010. The Islamic presence in Europe is exemplified as perceived and as self-perceived; as Moroccans and as Senegalese; and in three countries: Spain, Italy and France. The main goal has been to gain a better knowledge about the Muslim migration experience in particular concerning integration in its social and economic dimensions. The most important source of information has been a series of interviews with migrants, the aim of which was to explore and present the Muslim migrants’ per- spective: their vision of the world, their terminology, their categorizations of different phenomena and how they define themselves. -

How French Perception Affects Muslim Integration Brittany P

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection Undergraduate Scholarship 8-25-2012 Immigration in France: How French Perception Affects Muslim Integration Brittany P. Eisenhut Butler University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses Part of the French and Francophone Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Eisenhut, Brittany P., "Immigration in France: How French Perception Affects Muslim Integration" (2012). Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection. Paper 210. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUTLER UNIVERSITY HONORS PROGRAM Honors Thesis Certification Please type all information in this section: Applicant Brittany P. Eisenhut (Name as it is to appear on diploma) Thesis title Immigration in France: How French Perception Affects Muslim Integration Intended date of commencement August 2012 ----------------------------------- Read, approved, and signed by: [.<1..-Z0IL Date ~ -2S-2Q~~ Date Reader(s) g-c1?-A2J'L- lOhl'Zc)f3 Date Certified by Date For Honors Program use: Level of Honors conferred: University Departmental Immigration in France: How French Perception Affects Muslim Integration A Thesis Presented to the Department of International Studies College of Liberal Arts and Sciences and The Honors Program of Butler University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation Honors Brittany P. Eisenhut 24 August 2012 1 Introduction Modern-day France is wrought with social tensions surrounding the issue of immigration and what it means for the country's national identity. -

Moroccan Migration to France: Historical Patterns and Effects on Assimilation

Moroccan Migration to France: Historical Patterns and Effects on Assimilation Master’s Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Department of Global Studies Professor Jytte Klausen In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Global Studies by Shayna Straus May 2016 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank both the former and current head of the Graduate Global Studies program, Professor Chandler Rosenberger and Professor Kristen Lucken respectively, for their interest and immense support during the formative stages of this thesis, as well as serving as invaluable professors at different stages of my education. I am also very grateful to my advisor, Professor Jytte Klausen, without whom this research would not have been possible. Her knowledge on immigration and Muslims living in the Western world is not only incredible, but also deeply inspiring. ii Migration from Morocco to France: A Historical Overview of Migration Patterns from 1912 to Present Day and Their Affects on Assimilation in the Destination Country A thesis presented to the Graduate Program in Global Studies Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Waltham, Massachusetts By Shayna Straus ABSTRACT This paper seeks to understand assimilation patterns of Moroccan immigrants in France. Through the study of quotidian Moroccan life, starting with the establishment of the French protectorate, both the reasons and conditions of migration are outlined. It is only through an extensive examination and deep understanding of these pre-migratory processes that behavior upon arrival in the receiving country can begin to be understood, and eventually predicted.