Between Tradition and Modernity: on Judaism and an Old-New Pedagogy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

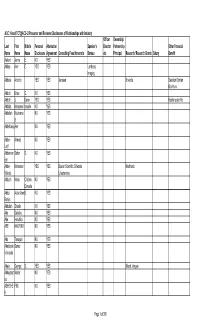

ACC14 and Tctacci2 Presenter and Reviewer Disclosures B.Pdf

ACC.14 and TCT@ACC-i2 Presenter and Reviewer Disclosures of Relationships with Industry Officer Ownership Last First Middle Personal Attestation Speaker's Director Partnership Other Financial Name Name Name Disclosure Agreement Consulting Fees Honoraria Bureau etc Principal Research/ Research Grants Salary Benefit Aaland Jenna E. NO YES Abbas Amr E. YES YES Lantheus Imaging Abbate Antonio YES YES Janssen Novartis Swedish Orphan Biovitrum Abbott Brian G. NO YES Abbott J. Dawn YES YES Boston scientific Abdalla Mohamed Ismaile NO YES Abdallah Mouhama NO YES d Abdelbaky Amr NO YES Abdel- Ahmed NO YES Latif Abdelmon Sahar S. NO YES eim Abdel- Mohamed YES YES Boston Scientific, Edwards Medtronic Wahab Lifesciences Abduch Maria Cristina NO YES Donadio Abdul Aizai Azan B. NO YES Rahim Abdullah Shuaib NO YES Abe Daisuke NO YES Abe Haruhiko NO YES ABE NAOYUKI NO YES Abe Takayuki NO YES Abedzade Sanaz NO YES h Anaraki Abela George S. YES YES Merck, Amgen Abhayarat Walter NO YES na ABHISHE FNU NO YES K Page 1 of 350 Officer Ownership Last First Middle Personal Attestation Speaker's Director Partnership Other Financial Name Name Name Disclosure Agreement Consulting Fees Honoraria Bureau etc Principal Research/ Research Grants Salary Benefit Abidi Syed NO YES Abidov Aiden NO YES Abi-samra Freddy Michel NO YES Abizaid Alexandre YES YES Abbott, Boston Scientific Abo- Elsayed NO YES Salem Abou- Alex NO YES Chebl AbouEzze Omar F NO YES ddine Aboulhosn Jamil A. YES YES GE Medical, Actelion United Therapeutics, Actelion Pharmaceuticals Pharmaceuticals Abraham Jacob NO YES Abraham JoEllyn Moore NO YES Abraham Maria Roselle NO YES Abraham Theodore P. -

400 Editor RABBI SHIMON HELINGER

ב"ה למען ישמעו • פרשת תצוה • 400 EDITOR RABBI SHIMON HELINGER PURIM A POTENT DAY INTENSE REJOICING The Rebbe once said: It’s obvious that we must distance ourselves entirely The Zohar notes that Purim is similar to Yom We read in the Gemara that on Purim one must drink from anything negative (“cursed be Haman”), HaKipurim. This means that what is accomplished “until he cannot differentiate (“ad d’lo yada”) between and seek to treasure and embrace all good things on Yom Kippur by fasting can be accomplished ‘cursed be Haman’ and ‘blessed be Mordechai.’ ” (“blessed be Mordechai”). That applies at any time. on Purim by rejoicing. Furthermore, the very The Gemara relates a story of two amoraim, Rabbah The unique aspect of Purim is that we can accomplish name Kipurim (“like Purim”), implies that Purim and Rav Zeira, who had their Purim seuda together, this by allowing our neshama to express itself freely. is the greater Yom-Tov, impacting a person sharing profound secrets of the Torah over a This kind of avoda is superior to serving HaShem by more powerfully. number of cups of wine. However, Rav Zeira was so means of conscious thought (yada). Indeed, in this Indeed, Chazal teach that when Moshiach comes, all overwhelmed by the intense kedusha of Rabbah’s kind of avoda we can resemble the Yidden at the the Yomim-Tovim will cease to exist; only the Yom- revelations that his neshama left his body. time of the Purim story who, when the inner power Tov of Purim will remain. Chassidus explains that of their neshamos surfaced, fulfilled all the mitzvos the joy and holiness of Purim are so great, that even faithfully, even to the point of mesiras nefesh. -

Sanhedrin 053.Pub

ט"ז אלול תשעז“ Thursday, Sep 7 2017 ן נ“ג סנהדרי OVERVIEW of the Daf Distinctive INSIGHT to apply stoning to other cases גזירה שוה Strangulation for adultery (cont.) The source of the (1 ואלא מכה אביו ואמו קא קשיא ליה, למיתי ולמיגמר מאוב וידעוני R’ Yoshiya’s opinion in the Beraisa is unsuccessfully וכו ‘ ליגמרו מאשת איש, דאי אתה רשאי למושכה להחמיר עליה וכו‘ .challenged at the bottom of 53b lists אלו הן הנסקלין Stoning T he Mishnah of (2 The Mishnah later derives other cases of stoning from a many cases which are punished with stoning. R’ Zeira notes gezeirah shavah from Ov and Yidoni. R’ Zeira questions that the Torah only specifies stoning explicitly in a handful גזירה שוה of cases, while the other cases are learned using a דמיהם בם or the words מות יומתו whether it is the words Rashi states that the cases where we find . אוב וידעוני that are used to make that gezeirah shavah. from -stoning explicitly are idolatry, adultery of a betrothed maid . דמיהם בם Abaye answers that it is from the words Abaye’s explanation is defended. en, violating the Shabbos, sorcery and cursing the name of R’ Acha of Difti questions what would have bothered R’ God. Aruch LaNer points out that there are three addition- Zeira had the gezeirah shavah been made from the words al cases where we find stoning mentioned outright (i.e., sub- ,mitting one’s children to Molech, inciting others to idolatry . מות יומתו In any case, there .( בן סורר ומורה—After R’ Acha of Difti suggests and rejects a number of and an recalcitrant son גזירה possible explanations Ravina explains what was troubling R’ are several cases of stoning which are derived from the R’ Zeira asks Abaye to identify the source from which . -

Source Sheet on Prohibitions on Loshon Ha-Ra and Motzi Shem Ra and Disclosing Another’S Confidential Secrets and Proper Etiquette for Speech

Source Sheet on Prohibitions on Loshon ha-ra and motzi shem ra and disclosing another’s confidential secrets and Proper Etiquette for Speech Deut. 24:9 - "Remember what the L-rd your G-d did unto Miriam by the way as you came forth out of Egypt." Specifically, she spoke against her brother Moses. Yerushalmi Berachos 1:2 Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai said, “Had I been at Mount Sinai at the moment when the torah was given to Yisrael I would have demanded that man should have been created with two mouths- one for Torah and prayer and other for mundane matters. But then I retracted and exclaimed that if we fail and speak lashon hara with only one mouth, how much more so would we fail with two mouths Bavli Arakhin15b R. Yochanan said in the name of R.Yosi ben Zimra: He who speaks slander, is as though he denied the existence of the Lord: With out tongue will we prevail our lips are our own; who is lord over us? (Ps.12:5) Gen R. 65:1 and Lev.R. 13:5 The company of those who speak slander cannot greet the Presence Sotah 5a R. Hisda said in the name of Mar Ukba: When a man speaks slander, the holy one says, “I and he cannot live together in the world.” So scripture: “He who slanders his neighbor in secret…. Him I cannot endure” (Ps. 101:5).Read not OTO “him’ but ITTO “with him [I cannot live] Deut.Rabbah 5:10 R.Mana said: He who speaks slander causes the Presence to depart from the earth below to heaven above: you may see foryourselfthat this is so.Consider what David said: “My soul is among lions; I do lie down among them that are aflame; even the sons of men, whose teeth are spears and arrows, and their tongue a sharp sword” (Ps.57:5).What follows directly ? Be Thou exalted O God above the heavens (Ps.57:6) .For David said: Master of the Universe what can the presence do on the earth below? Remove the Presence from the firmament. -

Dialogic Pedagogy and Reading Comprehension: Examining the Effect of Dialogic

Dialogic Pedagogy and Reading Comprehension: Examining the Effect of Dialogic Support on Reading Comprehension for Adolescents James Carroll Hill Dissertation submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Curriculum and Instruction Trevor T. Stewart, Chair Heidi Anne E. Mesmer Amy P. Azano Bonnie S. Billingsley March 24, 2020 Blacksburg, VA Keywords: English Language Arts, dialogic pedagogy, reading comprehension, intertextuality Dialogic Pedagogy and Reading Comprehension: Examining the Effect of Dialogic Support on Reading Comprehension for Adolescents James Carroll Hill ABSTRACT The reading comprehension scores of students in secondary education have been stagnant since the collection of national statistics on reading comprehension began (National Assessment on Educational Progress [NAEP], 2015, 2017, 2019). This study explored the effect of providing dialogic and thematic support on reading comprehension and intertextuality. The theories of dialogic pedagogy (Fecho, 2011; Stewart, 2019) and cognitive flexibility in reading (Spiro et al., 1987), along with the construction- integration model of reading comprehension (Kinstch, 2004) formed the foundation for this study. The study focused on the reading comprehension and ability to make connections across texts of 184 participants enrolled in 9th or 10th grade English classes in a high school in the Appalachian region of the southeastern United States. Methods included an experimental study which required participants to participate in two rounds of testing: the Nelson Denny Reading Test to provide reading levels and the Thematically Connected Dialogic Pedagogy (TCDP) testing which introduced dialogic and thematic support for reading comprehension and intertextuality. -

Miriyam Goldman OA Thesis 9Dec20.Pdf (247.7Kb)

The Living Stone: The Talmudic Paradox of the Seventh Month Gestational Viability vs. the Eighth Month Non-Viability Presented to the S. Daniel Abraham Honors Program in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Completion of the Program Stern College for Women Yeshiva University December 9, 2020 Miriyam A. Goldman Mentor: Rabbi Dr. Richard Weiss, Biology Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………….…. 4 Background to Pregnancy ……………………………………………………………………… 5 Talmudic Sources on the Dilemma ……………………………………………………………. 6 Meforshim on the Dilemma ……………………………………………………………………. 9 Secular Sources of the Dilemma ………………………………………………………………. 11 The Significance of Hair and Nails in Terms of Viability……………………………….……... 14 The Definition of Nefel’s Impact on Viability ……………………………………………….. 17 History of Premature Survival ………………………………………………………………… 18 Statistics on Prematurity ………………………………………………………………………. 19 Developmental Differences Between Seventh and Eighth Months ……………………….…. 20 Contemporary Talmudic Balance of the Dilemma..…………………………………….…….. 22 Contemporary Secular Balance of the Dilemma .……………………………………….…….. 24 Evaluation of Talmudic Accreditation …………………………………………………..…...... 25 Interviews with Rabbi Eitan Mayer, Rabbi Daniel Stein, and Rabbi Dr. Richard Weiss .…...... 27 Conclusion ………………………………………………………………………………….…. 29 References…..………………………………………………………………………………..… 34 2 Abstract This paper reviews the viability of premature infants, specifically the halachic status of those born in -

Dialogic Pedagogy and Semiotic-Dialogic Inquiry Into Visual Literacies and Augmented Reality

ISSN: 2325-3290 (online) Dialogic pedagogy and semiotic-dialogic inquiry into visual literacies and augmented reality Zoe Hurley Zayed University, Dubai Abstract Technological determinism has been driving conceptions of technology enhanced learning for the last two decades at least. The abrupt shift to the emergency delivery of online courses during COVID-19 has accelerated big tech’s coup d’état of higher education, perhaps irrevocably. Yet, commercial technologies are not necessarily aligned with dialogic conceptions of learning while a technological transmission model negates learners’ input and interactions. Mikhail Bakhtin viewed words as the multivocal bridge to social thought. His theory of the polysemy of language, that has subsequently been termed dialogism, has strong correlations with the semiotic philosophy of American pragmatist Charles Sanders Peirce. Peirce’s semiotic philosophy of signs extends far beyond words, speech acts, linguistics, literary genres, and/or indeed human activity. This study traces links between Bakhtin’s dialogism with Peirce’s semiotics. Conceptual synthesis develops the semiotic-dialogic framework. Taking augmented reality as a theoretical case, inquiry illustrates that while technologies are subsuming traditional pedagogies, teachers and learners, this does not necessarily open dialogic learning. This is because technologies are never dialogic, in and of themselves, although semiotic learning always involves social actors’ interpretations of signs. Crucially, semiotic-dialogism generates theorising of the visual literacies required by learners to optimise technologies for dialogic learning. Key Words: Dialogism / signs / semiotics / questioning / opening / augmented reality / technologies Zoe Hurley (PhD, Lancaster University, UK) is the Assistant Dean for Student Affairs in the College of Communication and Media Sciences at Zayed University, Dubai, United Arab Emirates. -

Learning from Jewish Education

ADVANCING THE LEARNING AGENDA IN JEWISH EDUCATION ADVANCING THE LEARNING AGENDA IN JEWISH EDUCATION Edited by JON A. LEVISOHN and JEFFREY S. KRESS Boston 2018 The research for this book and its publication were made possible by the generous support of the Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Center for Studies in Jewish Education, a partnership between Brandeis University and the Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Foundation of Cleveland, Ohio. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Levisohn, Jon A., editor. | Kress, Jeffrey S., editor. Title: Advancing the learning agenda in Jewish education / Jon A. Levisohn and Jeffrey S. Kress, editors. Description: Boston: Academic Studies Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: LCCN 2018023237 (print) | LCCN 2018024454 (ebook) | ISBN 9781618117540 (ebook) | ISBN 9781618117533 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781618118790 (pbk.) Subjects: LCSH: Jews—Education. | Jewish religious education. | Judaism—Study and teaching. Classification: LCC LC715 (ebook) | LCC LC715 .A33 2018 (print) | DDC 296.6/8—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018023237 © Academic Studies Press, 2018 ISBN 978-1-618117-53-3 (hardcover) ISBN 978-1-618117-54-0 (electronic) ISBN 978-1-618118-79-0 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-644692-83-7 (open access) Book design by Kryon Publishing Services (P) Ltd. www.kryonpublishing.com Cover design by Ivan Grave Published by Academic Studies Press 28 Montfern Avenue Brighton, MA 02135, USA [email protected] www.academicstudiespress.com Effective October 15th, 2019, this book will be subject to a CC-BY-NC license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. Other than as provided by these licenses, no part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or displayed by any electronic or mechanical means without permission from the publisher or as permitted by law. -

Shavuot 5780 Divrei Torah

Shavuot 5780 Divrei Torah Sponsored by: Debbie and Orin Golubtchik in honor of: The yahrzeits of Orin's parents חביבה בת שמואל משה בן חיים ליב Barbara and Simcha Hochman & family in memory of: • Simcha’s father, Rabbi Jonas Hochman a"h and • Gedalya ben Avraham, Blima bat Yaakov, Eeta bat Noach and Chaya bat Gedalya, who were murdered upon arrival at Birkenau on the 2nd day Shavuot. Table of Contents Page 3 Forward by Rabbi Adler ”That which you can and cannot do on Yom Tov אכל נפש“ Page 5 Yaakov Blau “Shifting voices in the narrative of Tanach” Page 9 Leeber Cohen “The Importance of Teaching Torah to Grandchildren” Page 11 Elchanan Dulitz “Bezchus Rabbi Dr. Baruch Tzvi ben R. Reuven Nassan z”l Mai Chanukah” Page 15 Martin Fineberg “Shavuos 5780 D’var Torah” Page 19 Yehuda Halpert “Ruth and Orpah’s Wedding Album: Fake News or Biblical Commentary” Page 23 Terry Novetsky “The “Mitzva” of Shavuot” Page 31 Yitzchak Shulman “Parshat Behaalotcha “ Page 33 Bernard Stahl The Meaning of Humility Page 41 Murray Sragow “Jews and Booze—A look at Jewish responses to Prohibition” Page 49 Mark Teicher “Intertextuality/Numerology” Page 50 Mark Zitter ”קרבנות של חג השבועות“ 2 Forward by Rabbi Adler Chaveireinu HaYikarim, Every year on the first night of Shavuot many of us get together for the purpose of learning with one another. There are multiple shiurim and many hours of chavruta learning . Unfortunately, in today’s climate we cannot learn with one another but we can learn from one another. Enclosed are a variety of Torah articles on many different topics which you are invited to enjoy during the course of Zman Matan Torahteinu. -

Tanya Sources.Pdf

The Way to the Tree of Life Jewish practice entails fulfilling many laws. Our diet is limited, our days to work are defined, and every aspect of life has governing directives. Is observance of all the laws easy? Is a perfectly righteous life close to our heart and near to our limbs? A righteous life seems to be an impossible goal! However, in the Torah, our great teacher Moshe, Moses, declared that perfect fulfillment of all religious law is very near and easy for each of us. Every word of the Torah rings true in every generation. Lesson one explores how the Tanya resolved these questions. It will shine a light on the infinite strength that is latent in each Jewish soul. When that unending holy desire emerges, observance becomes easy. Lesson One: The Infinite Strength of the Jewish Soul The title page of the Tanya states: A Collection of Teachings ספר PART ONE לקוטי אמרים חלק ראשון Titled הנקרא בשם The Book of the Beinonim ספר של בינונים Compiled from sacred books and Heavenly מלוקט מפי ספרים ומפי סופרים קדושי עליון נ״ע teachers, whose souls are in paradise; based מיוסד על פסוק כי קרוב אליך הדבר מאד בפיך ובלבבך לעשותו upon the verse, “For this matter is very near to לבאר היטב איך הוא קרוב מאד בדרך ארוכה וקצרה ”;you, it is in your mouth and heart to fulfill it בעזה״י and explaining clearly how, in both a long and short way, it is exceedingly near, with the aid of the Holy One, blessed be He. "1 of "393 The Way to the Tree of Life From the outset of his work therefore Rav Shneur Zalman made plain that the Tanya is a guide for those he called “beinonim.” Beinonim, derived from the Hebrew bein, which means “between,” are individuals who are in the middle, neither paragons of virtue, tzadikim, nor sinners, rishoim. -

Dialogic Pedagogy for a Post-Truth World

ISSN: 2325-3290 (online) Whose discourse? Dialogic pedagogy for a post-truth world Robin Alexander University of Cambridge, UK Abstract If, as evidence shows, well-founded classroom dialogue improves student engagement and learning, the logical next step is to take it to scale. However, this presumes consensus on definitions and purposes, whereas accounts of dialogue and dialogic teaching/pedagogy/education range from the narrowly technical to the capaciously ontological. This paper extends the agenda by noting the widening gulf between discourse and values within the classroom and outside it, and the particular challenge to both language and democracy of a currently corrosive alliance of digital technology and “post-truth” political rhetoric. Dialogic teaching is arguably an appropriate and promising response, and an essential ingredient of democratic education, but only if it is strengthened by critical engagement with four imperatives whose vulnerability in contemporary public discourse attests to their importance in the classroom, the more so given their problematic nature: language, voice, argument and truth.1 Key Words: Dialogue; pedagogy; democracy; language; voice; argument; truth Robin Alexander is Fellow of Wolfson College, University of Cambridge, Professor of Education Emeritus at the University of Warwick, Fellow of the British Academy, and past President of the British Association for International and Comparative Education. He has held senior posts at four UK universities and visiting positions in other countries. He directed the Cambridge Primary Review, the UK’s biggest enquiry into public primary/elementary education, and has worked extensively in development education, especially in India. His research and writing, whose prizes include the AERA Outstanding Book Award, explore policy, pedagogy, culture, primary schooling, comparative and development education, with classroom talk a prominent subset culminating to date in the successful large-scale trial of his framework for dialogic teaching. -

Fall 2019 Section 001 Syllabus

For Posting GEORGE MASON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF EDUCATION AND HUMAN DEVELOPMENT GRADUATE SCHOOL OF EDUCATION Ph.D. in Education Program EDUC 883.001 CRN 18098- Seminar in Sociocultural Theory 3 Credits, Fall 2019 Tuesdays, 7:10-10:00 Class Location: Thompson Hall 1020 PROFESSOR: Name: Dr. Shelley D. Wong Office Hours: Tuesdays 5:15-6:45 p.m. and by appointment Office Location: Thompson Hall 1505, Fairfax campus Office Phone: (703) 993-3513 Email: [email protected] Prerequisites Admission to PhD program in CEHD, or permission of instructor. University Catalog Course Description Explores and analyzes the theoretical contributions of sociocultural theory. Focuses on the growing body of contemporary research on literacy, equity in education and emancipatory teaching for diverse students. Course Overview In this course we will be reading three major foundational socio-cultural primary texts: Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the oppressed, Lev Vygotsky’s Mind in society and Mikhail Bakhtin’s Speech genres and other late essays. We will also read articles, books and educational commentaries about Freire, Vygotsky and Bakhtin by scholars in the fields of Multilingual Multicultural Education as well as sociocultural readings from specializations of interest to students in the course. Because reading and dialogue about these major theorists is at the heart of the course participants in this course will keep and share journals and provide peer feedback to deepen interdisciplinary engagement with the major sociocultural theories and applications to foster a critical community of scholars. Course Delivery Method This course will be delivered using a seminar format. The seminar format of EDUC 883 requires honest and respectful participation of all students.