Shavuot Shiur

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Halachic and Hashkafic Issues in Contemporary Society 91 - Hand Shaking and Seat Switching Ou Israel Center - Summer 2018

5778 - dbhbn ovrct [email protected] 1 sxc HALACHIC AND HASHKAFIC ISSUES IN CONTEMPORARY SOCIETY 91 - HAND SHAKING AND SEAT SWITCHING OU ISRAEL CENTER - SUMMER 2018 A] SHOMER NEGIAH - THE ISSUES • What is the status of the halacha of shemirat negiah - Deoraita or Derabbanan? • What kind of touching does it relate to? What about ‘professional’ touching - medical care, therapies, handshaking? • Which people does it relate to - family, children, same gender? • How does it inpact on sitting close to someone of the opposite gender. Is one required to switch seats? 1. THE WAY WE LIVE NOW: THE ETHICIST. Between the Sexes By RANDY COHEN. OCT. 27, 2002 The courteous and competent real-estate agent I'd just hired to rent my house shocked and offended me when, after we signed our contract, he refused to shake my hand, saying that as an Orthodox Jew he did not touch women. As a feminist, I oppose sex discrimination of all sorts. However, I also support freedom of religious expression. How do I balance these conflicting values? Should I tear up our contract? J.L., New York This culture clash may not allow you to reconcile the values you esteem. Though the agent dealt you only a petty slight, without ill intent, you're entitled to work with someone who will treat you with the dignity and respect he shows his male clients. If this involved only his own person -- adherence to laws concerning diet or dress, for example -- you should of course be tolerant. But his actions directly affect you. And sexism is sexism, even when motivated by religious convictions. -

ACC14 and Tctacci2 Presenter and Reviewer Disclosures B.Pdf

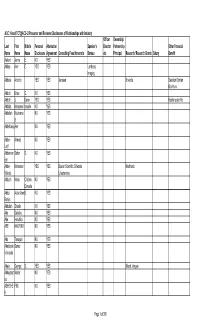

ACC.14 and TCT@ACC-i2 Presenter and Reviewer Disclosures of Relationships with Industry Officer Ownership Last First Middle Personal Attestation Speaker's Director Partnership Other Financial Name Name Name Disclosure Agreement Consulting Fees Honoraria Bureau etc Principal Research/ Research Grants Salary Benefit Aaland Jenna E. NO YES Abbas Amr E. YES YES Lantheus Imaging Abbate Antonio YES YES Janssen Novartis Swedish Orphan Biovitrum Abbott Brian G. NO YES Abbott J. Dawn YES YES Boston scientific Abdalla Mohamed Ismaile NO YES Abdallah Mouhama NO YES d Abdelbaky Amr NO YES Abdel- Ahmed NO YES Latif Abdelmon Sahar S. NO YES eim Abdel- Mohamed YES YES Boston Scientific, Edwards Medtronic Wahab Lifesciences Abduch Maria Cristina NO YES Donadio Abdul Aizai Azan B. NO YES Rahim Abdullah Shuaib NO YES Abe Daisuke NO YES Abe Haruhiko NO YES ABE NAOYUKI NO YES Abe Takayuki NO YES Abedzade Sanaz NO YES h Anaraki Abela George S. YES YES Merck, Amgen Abhayarat Walter NO YES na ABHISHE FNU NO YES K Page 1 of 350 Officer Ownership Last First Middle Personal Attestation Speaker's Director Partnership Other Financial Name Name Name Disclosure Agreement Consulting Fees Honoraria Bureau etc Principal Research/ Research Grants Salary Benefit Abidi Syed NO YES Abidov Aiden NO YES Abi-samra Freddy Michel NO YES Abizaid Alexandre YES YES Abbott, Boston Scientific Abo- Elsayed NO YES Salem Abou- Alex NO YES Chebl AbouEzze Omar F NO YES ddine Aboulhosn Jamil A. YES YES GE Medical, Actelion United Therapeutics, Actelion Pharmaceuticals Pharmaceuticals Abraham Jacob NO YES Abraham JoEllyn Moore NO YES Abraham Maria Roselle NO YES Abraham Theodore P. -

400 Editor RABBI SHIMON HELINGER

ב"ה למען ישמעו • פרשת תצוה • 400 EDITOR RABBI SHIMON HELINGER PURIM A POTENT DAY INTENSE REJOICING The Rebbe once said: It’s obvious that we must distance ourselves entirely The Zohar notes that Purim is similar to Yom We read in the Gemara that on Purim one must drink from anything negative (“cursed be Haman”), HaKipurim. This means that what is accomplished “until he cannot differentiate (“ad d’lo yada”) between and seek to treasure and embrace all good things on Yom Kippur by fasting can be accomplished ‘cursed be Haman’ and ‘blessed be Mordechai.’ ” (“blessed be Mordechai”). That applies at any time. on Purim by rejoicing. Furthermore, the very The Gemara relates a story of two amoraim, Rabbah The unique aspect of Purim is that we can accomplish name Kipurim (“like Purim”), implies that Purim and Rav Zeira, who had their Purim seuda together, this by allowing our neshama to express itself freely. is the greater Yom-Tov, impacting a person sharing profound secrets of the Torah over a This kind of avoda is superior to serving HaShem by more powerfully. number of cups of wine. However, Rav Zeira was so means of conscious thought (yada). Indeed, in this Indeed, Chazal teach that when Moshiach comes, all overwhelmed by the intense kedusha of Rabbah’s kind of avoda we can resemble the Yidden at the the Yomim-Tovim will cease to exist; only the Yom- revelations that his neshama left his body. time of the Purim story who, when the inner power Tov of Purim will remain. Chassidus explains that of their neshamos surfaced, fulfilled all the mitzvos the joy and holiness of Purim are so great, that even faithfully, even to the point of mesiras nefesh. -

1 Jews, Gentiles, and the Modern Egalitarian Ethos

Jews, Gentiles, and the Modern Egalitarian Ethos: Some Tentative Thoughts David Berger The deep and systemic tension between contemporary egalitarianism and many authoritative Jewish texts about gentiles takes varying forms. Most Orthodox Jews remain untroubled by some aspects of this tension, understanding that Judaism’s affirmation of chosenness and hierarchy can inspire and ennoble without denigrating others. In other instances, affirmations of metaphysical differences between Jews and gentiles can take a form that makes many of us uncomfortable, but we have the legitimate option of regarding them as non-authoritative. Finally and most disturbing, there are positions affirmed by standard halakhic sources from the Talmud to the Shulhan Arukh that apparently stand in stark contrast to values taken for granted in the modern West and taught in other sections of the Torah itself. Let me begin with a few brief observations about the first two categories and proceed to somewhat more extended ruminations about the third. Critics ranging from medieval Christians to Mordecai Kaplan have directed withering fire at the doctrine of the chosenness of Israel. Nonetheless, if we examine an overarching pattern in the earliest chapters of the Torah, we discover, I believe, that this choice emerges in a universalist context. The famous statement in the Mishnah (Sanhedrin 4:5) that Adam was created singly so that no one would be able to say, “My father is greater than yours” underscores the universality of the original divine intent. While we can never know the purpose of creation, one plausible objective in light of the narrative in Genesis is the opportunity to actualize the values of justice and lovingkindness through the behavior of creatures who subordinate themselves to the will 1 of God. -

Sanhedrin 053.Pub

ט"ז אלול תשעז“ Thursday, Sep 7 2017 ן נ“ג סנהדרי OVERVIEW of the Daf Distinctive INSIGHT to apply stoning to other cases גזירה שוה Strangulation for adultery (cont.) The source of the (1 ואלא מכה אביו ואמו קא קשיא ליה, למיתי ולמיגמר מאוב וידעוני R’ Yoshiya’s opinion in the Beraisa is unsuccessfully וכו ‘ ליגמרו מאשת איש, דאי אתה רשאי למושכה להחמיר עליה וכו‘ .challenged at the bottom of 53b lists אלו הן הנסקלין Stoning T he Mishnah of (2 The Mishnah later derives other cases of stoning from a many cases which are punished with stoning. R’ Zeira notes gezeirah shavah from Ov and Yidoni. R’ Zeira questions that the Torah only specifies stoning explicitly in a handful גזירה שוה of cases, while the other cases are learned using a דמיהם בם or the words מות יומתו whether it is the words Rashi states that the cases where we find . אוב וידעוני that are used to make that gezeirah shavah. from -stoning explicitly are idolatry, adultery of a betrothed maid . דמיהם בם Abaye answers that it is from the words Abaye’s explanation is defended. en, violating the Shabbos, sorcery and cursing the name of R’ Acha of Difti questions what would have bothered R’ God. Aruch LaNer points out that there are three addition- Zeira had the gezeirah shavah been made from the words al cases where we find stoning mentioned outright (i.e., sub- ,mitting one’s children to Molech, inciting others to idolatry . מות יומתו In any case, there .( בן סורר ומורה—After R’ Acha of Difti suggests and rejects a number of and an recalcitrant son גזירה possible explanations Ravina explains what was troubling R’ are several cases of stoning which are derived from the R’ Zeira asks Abaye to identify the source from which . -

Source Sheet on Prohibitions on Loshon Ha-Ra and Motzi Shem Ra and Disclosing Another’S Confidential Secrets and Proper Etiquette for Speech

Source Sheet on Prohibitions on Loshon ha-ra and motzi shem ra and disclosing another’s confidential secrets and Proper Etiquette for Speech Deut. 24:9 - "Remember what the L-rd your G-d did unto Miriam by the way as you came forth out of Egypt." Specifically, she spoke against her brother Moses. Yerushalmi Berachos 1:2 Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai said, “Had I been at Mount Sinai at the moment when the torah was given to Yisrael I would have demanded that man should have been created with two mouths- one for Torah and prayer and other for mundane matters. But then I retracted and exclaimed that if we fail and speak lashon hara with only one mouth, how much more so would we fail with two mouths Bavli Arakhin15b R. Yochanan said in the name of R.Yosi ben Zimra: He who speaks slander, is as though he denied the existence of the Lord: With out tongue will we prevail our lips are our own; who is lord over us? (Ps.12:5) Gen R. 65:1 and Lev.R. 13:5 The company of those who speak slander cannot greet the Presence Sotah 5a R. Hisda said in the name of Mar Ukba: When a man speaks slander, the holy one says, “I and he cannot live together in the world.” So scripture: “He who slanders his neighbor in secret…. Him I cannot endure” (Ps. 101:5).Read not OTO “him’ but ITTO “with him [I cannot live] Deut.Rabbah 5:10 R.Mana said: He who speaks slander causes the Presence to depart from the earth below to heaven above: you may see foryourselfthat this is so.Consider what David said: “My soul is among lions; I do lie down among them that are aflame; even the sons of men, whose teeth are spears and arrows, and their tongue a sharp sword” (Ps.57:5).What follows directly ? Be Thou exalted O God above the heavens (Ps.57:6) .For David said: Master of the Universe what can the presence do on the earth below? Remove the Presence from the firmament. -

The Generic Transformation of the Masoretic Text of Qohelet 9. 7-10 in the Targum Qohelet and Qohelet Midrash Rabbah

Durham E-Theses Wine, women and work: the generic transformation of the Masoretic text of Qohelet 9. 7-10 in the Targum Qohelet and Qohelet Midrash Rabbah Hardy, John Christopher How to cite: Hardy, John Christopher (1995) Wine, women and work: the generic transformation of the Masoretic text of Qohelet 9. 7-10 in the Targum Qohelet and Qohelet Midrash Rabbah, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/5403/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 WINE, WOMEN AND WORK: THE GENERIC TRANSFORMATION OF THE MA50RETIC TEXT OF QOHELET 9. 7-10 IN THE TARGUM QOHELET AND QOHELET MIDRASH RABBAH John Christopher Hardy This tnesis seeks to understand the generic changes wrought oy targum Qonelet and Qoheiet raidrash rabbah upon our home-text, the masoretes' reading ot" woh. -

RUTH Chapters 3, 4 This Is Already Our Last Study of Ruth. While This

RUTH Chapters 3, 4 This is already our last study of Ruth. While this book is very short, it gives us much insight into many important questions about life, such as where God is, in difficult times, and why sometimes He waits so long before He acts. Also, it is through two faithful women, that we learn so much about God’s workings in the believers’ lives. Naomi and Ruth, both teach us how to be patient and hopeful, in hard times. Throughout the tragedies of losing their husbands and being reduced to poverty, they did not believe that God had forsaken them. They often spoke of Him so reverently. Right in the midst of their ordeal, when Naomi told Ruth that it would be better for her to stay in Moab because she had nothing to offer her, she pronounced these words: The LORD deal kindly … (Ruth1:8), "The LORD grant that you may find rest (Ruth1:9). She was not mad at God for her situation. Ruth responded in like manner and said: Where you die, I will die, And there will I be buried. The LORD do so to me, and more also, If anything but death parts you and me." (Ruth 1:17) These women knew their God well, and when the time was right, He responded to their faith. When He replied, He acted in wonderful ways and with great blessings. We have seen that when Ruth went out to find food, the Scriptures said: And she happened to come to the part of the field belonging to Boaz,(Ruth 2:3). -

Sinful Thoughts: Comments on Sin, Failure, Free Will, and Related Topics Based on David Bashevkin’S New Book Sin•A•Gogue: Sin and Failure in Jewish Thought

Sinful Thoughts: Comments on Sin, Failure, Free Will, and Related Topics Based on David Bashevkin’s new book Sin•a•gogue: Sin and Failure in Jewish Thought Sinful Thoughts: Comments on Sin, Failure, Free Will, and Related Topics Based on David Bashevkin’s new book Sin•a•gogue: Sin and Failure in Jewish Thought (Boston: Academic Studies Press, 2019) By Rabbi Yitzchok Oratz A Bashevkin-inspired Bio Blurb:[1] Rabbi Yitzchok Oratz is Rabbi of the Monmouth Torah Links community in Marlboro, NJ. His writings can be found in various rabbinic and popular journals, including Hakira, Ohr Yisroel, Nehoroy, Nitay Ne’emanim, and on Aish, Times of Israel, Torah Links, Seforim Blog, and elsewhere. His writings are rejected as often as they are accepted, and the four books he is currently working on will likely never see the light of day. “I’d rather laugh[2] with the sinners than cry with the saints; the sinners are much more fun.”[3] Fortunate is the man who follows not the advice of the wicked, nor stood in the path of the sinners, nor sat in the session of the scorners. (Psalms 1:1) One who hopes is always happy [and] without pain . hope keeps one alive . even one who has minimal good deeds . has hope . one who hopes, even if he enters Hell, he will be taken out . his hope is his purity, literally the Mikvah [4] of Yisroel . and this is the secret of repentance . (Ramchal, Derush ha-Kivuy) [5] Rabbi David Bashevkin is a man deeply steeped in sin. -

Poem from "Bechadarav” וירדחב, Trans. Yaakov

TORAT BAVEL, TORAT ERETZ YISRAEL LEAH ROSENTAL I [email protected] trans. Yaakov David Shulman ,בחדריו ”Poem from "Bechadarav The Clarity of The Land Of Israel My heart yearns for the clarity of the land of Israel For the faith of the land of Israel For the holiness of the land of Israel Where can I find the joy of the land of Israel The inner calm of the land of Israel The closeness to the Divine of the land of Israel The truth of the land of Israel The might and power of the land of Israel The trust of the land of Israel Have mercy, Hashem, have compassion Compassionate and gracious God Be merciful Make it possible for me to come back to you totally Bring me back to Your beautiful land Make it possible for me to see the joy of Your people To rejoice with Your heirs Have compassion, have compassion Compassionate Father Have mercy, liberate, liberating God 1|7 TORAT BAVEL, TORAT ERETZ YISRAEL LEAH ROSENTAL I [email protected] תלמוד בבלי - מסכת סנהדרין Babylonian Talmud - Sanhedrin 24a דף כד עמוד א אמר רבי אושעיא: מאי דכתיב R. Oshaia said: What is the meaning of the verse, And I (זכריה י"א) "ואקח לי )את( שני took unto me the two staves; the one I called No'am מקלות לאחד קראתי נועם — ?[graciousness] and the other I called 'hoblim' [binders] ולאחד קראתי חובלים", נועם - No'am' refers to the scholars of Palestine, who treat each' אלו תלמידי חכמים שבארץ ישראל, שמנעימין זה לזה other graciously [man'imim] when engaged in halachic בהלכה. -

From Falashas to Ethiopian Jews

FROM FALASHAS TO ETHIOPIAN JEWS: THE EXTERNAL INFLUENCES FOR CHANGE C. 1860-1960 BY DANIEL P. SUMMERFIELD A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF LONDON (SCHOOL OF ORIENTAL AND AFRICAN STUDIES) FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (PhD) 1997 ProQuest Number: 10673074 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673074 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT The arrival of a Protestant mission in Ethiopia during the 1850s marks a turning point in the history of the Falashas. Up until this point, they lived relatively isolated in the country, unaffected and unaware of the existence of world Jewry. Following this period and especially from the beginning of the twentieth century, the attention of certain Jewish individuals and organisations was drawn to the Falashas. This contact initiated a period of external interference which would ultimately transform the Falashas, an Ethiopian phenomenon, into Ethiopian Jews, whose culture, religion and identity became increasingly connected with that of world Jewry. It is the purpose of this thesis to examine the external influences that implemented and continued the process of transformation in Falasha society which culminated in their eventual emigration to Israel. -

Application for Admission Yeshivas Ohr Yechezkel 2020-2021 Mesivta Ateres Tzvi the Wisconsin Institute for Torah Study 3288 N

APPLICATION FOR ADMISSION YESHIVAS OHR YECHEZKEL 2020-2021 MESIVTA ATERES TZVI THE WISCONSIN INSTITUTE FOR TORAH STUDY 3288 N. Lake Dr. Milwaukee, WI 53211 (414) 963-9317 PLEASE TYPE OR PRINT CLEARLY APPLICANT APPLICANT'S NAME (LAST) FIRST M.I. HEBREW NAME APPLICANT'S ADDRESS CITY STATE ZIP CODE HOME PHONE PRIMARY FAMILY E-MAIL ADDRESS PRESENT SCHOOL PRESENT GRADE PLACE OF BIRTH DATE OF BIRTH NAME PREFERRED TO BE CALLED PARENTS FATHER’S NAME (LAST) FIRST TITLE HEBREW NAME FATHER'S ADDRESS - (if different from above) CITY STATE ZIP CODE FATHER'S OCCUPATION HOME PHONE EMAIL ADDRESS CELL PHONE OFFICE PHONE SYNAGOGUE AFFILIATION SYNAGOGUE RABBI MOTHER'S NAME (LAST) FIRST TITLE MAIDEN NAME HEBREW NAME MOTHER'S ADDRESS - (if different from above) CITY STATE ZIP CODE MOTHER'S OCCUPATION HOME PHONE (if different from above) CELL PHONE OFFI CE PHONE EMAIL ADDRESS SYNAGOGUE AFFILIATION – (if different from above) SYNAGOGUE RABBI – (if different from above) PARENTS' AFFILIATION WITH JEWISH ORGANIZATIONS, (RELIGIOUS, COMMUNAL, EDUCATIONAL, ETC.) SIBLINGS NAME SCHOOL AGE GRADE EDUCATIONAL DATA LIST CHRONOLOGICALLY ALL THE SCHOOLS THAT APPLICANT HAS ATTENDED NAME OF SCHOOL CITY DATES OF ATTENDANCE GRADUATED (Y OR N) DESCRIBE THE COURSES APPLICANT HAS TAKEN THIS YEAR GEMORAH: Include the mesechta currently being learned, the amount of blatt expected to be learned this year, the length of the Gemorah shiur each day and the meforshim regularly learned MATH: Provide course name and describe the material studied EXTRA CURRICULAR LEARNING: Describe any learning outside of school (Limud, Days, Time) LIST CHRONOLOGICALLY THE SUMMER CAMPS THAT APPLICANT HAS ATTENDED NAME CITY DATES IN WHICH ORGANIZATIONS AND/OR EXTRA CURRICULAR ACTIVITIES HAS APPLICANT PARTICIPATED IN SCHOOL AND IN THE COMMUNITY? NAME DATES INDEPENDENT EVALUATIONS Section 1 Has your son ever been evaluated or diagnosed for any developmental or learning issues? Yes No If yes, please state the reason or nature of the tests.