"Have To" History - Who Was Sargon (Of Akkad)? Stuff You Don’T Really Want to Know (But for Some Reason Have To) About Sargon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Akkadian Empire

RESTRICTED https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-hccc-worldcivilization/chapter/the-akkadian-empire/ The Akkadian Empire LEARNING OBJECTIVE • Describe the key political characteristics of the Akkadian Empire KEY POINTS • The Akkadian Empire was an ancient Semitic empire centered in the city of Akkad and its surrounding region in ancient Mesopotamia, which united all the indigenous Akkadian speaking Semites and the Sumerian speakers under one rule within a multilingual empire. • King Sargon, the founder of the empire, conquered several regions in Mesopotamia and consolidated his power by instating Akaddian officials in new territories. He extended trade across Mesopotamia and strengthened the economy through rain-fed agriculture in northern Mesopotamia. • The Akkadian Empire experienced a period of successful conquest under Naram-Sin due to benign climatic conditions, huge agricultural surpluses, and the confiscation of wealth. • The empire collapsed after the invasion of the Gutians. Changing climatic conditions also contributed to internal rivalries and fragmentation, and the empire eventually split into the Assyrian Empire in the north and the Babylonian empire in the south. TERMS Gutians A group of barbarians from the Zagros Mountains who invaded the Akkadian Empire and contributed to its collapse. Sargon The first king of the Akkadians. He conquered many of the surrounding regions to establish the massive multilingual empire. Akkadian Empire An ancient Semitic empire centered in the city of Akkad and its surrounding region in ancient Mesopotamia. Cuneiform One of the earliest known systems of writing, distinguished by its wedge-shaped marks on clay tablets, and made by means of a blunt reed for a stylus. Semites RESTRICTED Today, the word “Semite” may be used to refer to any member of any of a number of peoples of ancient Southwest Asian descent, including the Akkadians, Phoenicians, Hebrews (Jews), Arabs, and their descendants. -

Antologia Della Letteratura Ittita

UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI PISA Dipartimento di Scienze storiche del mondo antico Giuseppe Del Monte ANTOLOGIA DELLA LETTERATURA ITTITA Servizio Editoriale Universitario di Pisa Aprile 2003 Azienda Regionale D.S.U. - PISA © SEU - Via Curtatone e Montanara 6 - 56126 Pisa - tel/fax 050/540120 aprile 2003 ii SOMMARIO CAPITOLO I. Iscrizioni reali e editti 1-41 a) Iscrizioni dei re di Kusara e Nesa 1. Dalla “Iscrizione di Anitta” 1 b) L’Antico Regno 1. Le “Gesta di Hattusili I” 3 2. Da un editto di Hattusili I 7 3. Dall’Editto di Telipinu 8 c) Il Medio Regno 1. Dagli Annali di Tuthalija I 14 2. Editto di Tuthalija I sulla giustizia 16 3. Dagli Annali di Arnuwanda I 17 4. Editto della Regina Ašmunikal sui mausolei reali 18 d) Il Nuovo Regno 1. Dalle Gesta di Suppiluliuma 20 2. Dagli Annali Decennali di Mursili II 27 3. Dalla Apologia di Hattusili III 32 4. Editto di Hattusili III per i figli di Mitannamuwa 37 5. Suppiluliuma II e la conquista di Alasija 39 CAPITOLO II. Trattati e accordi 43-77 a) Il Medio Regno 1. Dal trattato di Tuthalija I con Šunašura di Kizuwatna 43 2. Da un trattato di Arnuwanda I con i Kaskei 45 3. Preghiera/trattato di Arnuwanda I con i Kaskei 46 4. Lista di ostaggi kaskei da Maşat Höyük/Tapika 51 5. Dalla “Requisitoria contro Madduwatta” 52 6. Dalle Istruzioni ai governatori delle province di frontiera 56 b) Il Nuovo Regno 1. Dal trattato di Suppiluliuma I con Aziru di Amurru 59 2. -

The Limits of Middle Babylonian Archives1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenstarTs The Limits of Middle Babylonian Archives1 susanne paulus Middle Babylonian Archives Archives and archival records are one of the most important sources for the un- derstanding of the Babylonian culture.2 The definition of “archive” used for this article is the one proposed by Pedersén: «The term “archive” here, as in some other studies, refers to a collection of texts, each text documenting a message or a statement, for example, letters, legal, economic, and administrative documents. In an archive there is usually just one copy of each text, although occasionally a few copies may exist.»3 The aim of this article is to provide an overview of the archives of the Middle Babylonian Period (ca. 1500-1000 BC),4 which are often 1 All kudurrus are quoted according to Paulus 2012a. For a quick reference on the texts see the list of kudurrus in table 1. 2 For an introduction into Babylonian archives see Veenhof 1986b; for an overview of differ- ent archives of different periods see Veenhof 1986a and Brosius 2003a. 3 Pedersén 1998; problems connected to this definition are shown by Brosius 2003b, 4-13. 4 This includes the time of the Kassite dynasty (ca. 1499-1150) and the following Isin-II-pe- riod (ca. 1157-1026). All following dates are BC, the chronology follows – willingly ignoring all linked problems – Gasche et. al. 1998. the limits of middle babylonian archives 87 left out in general studies,5 highlighting changes in respect to the preceding Old Babylonian period and problems linked with the material. -

Sargon of Akkade and His God

Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hung. Volume 69 (1), 63–82 (2016) DOI: 10.1556/062.2016.69.1.4 SARGON OF AKKADE AND HIS GOD COMMENTS ON THE WORSHIP OF THE GOD OF THE FATHER AMONG THE ANCIENT SEMITES STEFAN NOWICKI Institute of Classical, Mediterranean and Oriental Studies, University of Wrocław ul. Szewska 49, 50-139 Wrocław, Poland e-mail: [email protected] The expression “god of the father(s)” is mentioned in textual sources from the whole area of the Fertile Crescent, between the third and first millennium B.C. The god of the fathers – aside from assumptions of the tutelary deity as a god of ancestors or a god who is a deified ancestor – was situated in the centre and the very core of religious life among all peoples that lived in the ancient Near East. This paper is focused on the importance of the cult of Ilaba in the royal families of the ancient Near East. It also investigates the possible source and route of spreading of the cult of Ilaba, which could have been created in southern Mesopotamia, then brought to other areas. Hypotheti- cally, it might have come to the Near East from the upper Euphrates. Key words: religion, Ilaba, royal inscriptions, Sargon of Akkade, god of the father, tutelary deity, personal god. The main aim of this study is to trace and describe the worship of a “god of the fa- ther”, known in Akkadian sources under the name of Ilaba, and his place in the reli- gious life of the ancient peoples belonging to the Semitic cultural circle. -

Arqueologias De Império» Consistem Em 17 Estudos Que Abrangem As Várias Áreas De HVMANITAS SVPPLEMENTVM • ESTUDOS MONOGRÁFICOS Investigação Da Antiguidade

Estas «Arqueologias de Império» consistem em 17 estudos que abrangem as várias áreas de HVMANITAS SVPPLEMENTVM • ESTUDOS MONOGRÁFICOS investigação da Antiguidade. A partir das fontes bíblicas, propõe-se uma estruturação de ISSN: 2182-8814 categorias e uma organização de semânticas como possíveis caminhos para o entendimento da ideia de «império». Para o caso egípcio, foca-se a problemática da periodização da História Apresentação: esta série destina-se a publicar estudos de fundo sobre um leque variado de egípcia e a terminologia utilizada para a definir. Para o universo dos impérios antigos da temas e perspetivas de abordagem (literatura, cultura, história antiga, arqueologia, história Mesopotâmia, trata-se a emergência da hegemonia paleobabilónica através da análise da arte, filosofia, língua e linguística), mantendo embora como denominador comum os da ideologia subjacente às políticas sociais e militares levadas a cabo por Hammurabi em Estudos Clássicos e sua projeção na Idade Média, Renascimento e receção na atualidade. dois momentos cruciais da história da Babilónia. Para o espaço da Anatólia e do território 58 OBRA PUBLICADA fenício/siro-palestinense, recorre-se a um método que colhe nas narrativas mítico-religiosas COM A COORDENAÇÃO elementos para o estudo das realidades políticas e apresenta-se uma reflexão sobre CIENTÍFICA Imperialismo no mundo colonial fenício. As civilizações e sociedades neomesopotâmicas estão representadas por estudos sobre contextos de violência, acerca de Jeremias e do Breve nota curricular sobre os autores do volume Império Neobabilónico, sobre Nabónido e ainda sobre os diferentes comportamentos dos reis da região relativamente ao culto de Marduk. Podemos também ler textos sobre a Arqueologias Delfim F. -

Revisiting the Conquest of Karkamiš During Mursili II's Year 9

Festschrift für Gernot Wilhelm anläßlich seines 65. Geburtstages am 28. Januar 2010 Copyright © Jeanette C. Fincke Copyright © ISLET Verlag, Dresden Schriftsatz: Jeanette C. Fincke Herstellung: Medienhaus Lißner, Dresden Printed in Germany ISBN 978-3-9808-4664-6 ISLET [email protected] www.islet-verlag.de Festschrift für Gernot Wilhelm anläßlich seines 65. Geburtstages am 28. Januar 2010 herausgegeben von Jeanette C. Fincke ISLET Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorwort .................................................................................................................. v InhaltsVerzeIchnIs ................................................................................................. vii schrIftenVerzeIchnIs Von Gernot wIlhelm ..................................................... xi tzVI abusch a neo-babylonian recension of maqlû : some observations on the re - duction of maqlû tablet VII and on the Development of two of Its In- cantations ........................................................................................................... 1 rukIye akDoG ̆an ein neues hethitisches keilschriftfragment eines festrituals ........................... 17 hartwIG altenmüller bemerkungen zum ostfeldzug Ptolemaios’ III. nach babylon und in die susiana im Jahre 246/245 ................................................................................ 27 alfonso archI Divination at ebla ............................................................................................ 45 Josef bauer sumerische kasussuffixe mit eingeschränkter -

Thesis, Revised Copyright

Views of Epic Transmission in Sargonic Tradition and the Bellerophon Saga By Copyright 2012 Cynthia Carolyn Polsley Cynthia C. Polsley Submitted to the graduate degree program in Classics and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Stanley Lombardo ________________________________ Anthony Corbeill ________________________________ Molly Zahn Date Defended: February 13, 2012 The Thesis Committee for Cynthia C. Polsley certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Views of Epic Transmission in Sargonic Tradition and the Bellerophon Saga ________________________________ Chairperson Stanley Lombardo Date approved: February 15, 2012 ii Abstract One of the most memorable tales in Homer’s Iliad is that of Bellerophon, the Corinthian hero sent as courier with a message deceitfully intended to arrange his death. A similar story is related in the Sumerian Sargon Legend of the eighteenth-century B.C.E., which tells of how Sargon of Akkad seized the kingdom of Uruk by divine aid. The motif of a treacherous letter is not the only similarity between general stories regarding Sargon and Bellerophon. Other shared themes include blood pollution, interactions with a queen, divine escort, and a restless wandering. Tales about Sargon and Bellerophon are disseminated across cultures. Sumerian and Akkadian texts describing Sargon’s exploits have been found in Egypt, Syria, and Anatolia, while Bellerophon’s adventures are described by storytellers of Greece and Rome. Beginning with the Sargon Legend and Homer’s Bellerophon, I explore the two narrative traditions primarily as case studies for epic transmission. I furthermore propose that cultural interaction and a complex network of oral and written storytelling contributed to the transmission of the traditions and motifs. -

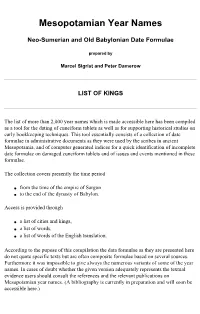

Mesopotamian Year Names

Mesopotamian Year Names Neo-Sumerian and Old Babylonian Date Formulae prepared by Marcel Sigrist and Peter Damerow LIST OF KINGS The list of more than 2,000 year names which is made accessible here has been compiled as a tool for the dating of cuneiform tablets as well as for supporting historical studies on early bookkeeping techniques. This tool essentially consists of a collection of date formulae in administrative documents as they were used by the scribes in ancient Mesopotamia, and of computer generated indices for a quick identification of incomplete date formulae on damaged cuneiform tablets and of issues and events mentioned in these formulae. The collection covers presently the time period ● from the time of the empire of Sargon ● to the end of the dynasty of Babylon. Access is provided through ● a list of cities and kings, ● a list of words, ● a list of words of the English translation. According to the pupose of this compilation the data formulae as they are presented here do not quote specific texts but are often composite formulae based on several sources. Furthermore it was impossible to give always the numerous variants of some of the year names. In cases of doubt whether the given version adequately represents the textual evidence users should consult the references and the relevant publications on Mesopotamian year names. (A bibliography is currently in preparation and will soon be accessible here.) History of the project The preparation of this electronic tool is an outcome of an unusual and long-lasting cooperation between an assyiologist and an historian of science at intervals over a period of more than 10 years. -

Reading Babylon Author(S): Marc Van De Mieroop Source: American Journal of Archaeology, Vol

Reading Babylon Author(s): Marc van de Mieroop Source: American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 107, No. 2 (Apr., 2003), pp. 257-275 Published by: Archaeological Institute of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40026077 . Accessed: 16/01/2015 12:01 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Archaeological Institute of America is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Journal of Archaeology. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.148.252.35 on Fri, 16 Jan 2015 12:01:43 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Reading Babylon MARC VAN DE MIEROOP Abstract Was this all the city signified, however? Was it A combined investigation of the archaeological re- only the expression of the power of its builder who mains and the ancient testimonies of the city of Babylon thus exemplified the oriental despot whose mega- in the days of King Nebuchadnezzar, during the sixth lomania is demonstrated the of his B.C., allows us to read the ideo- by grandeur city? century city's multiple This article will an alternativesemiotic read- logical messages. The concern of the article is not with provide the identification of specific monuments, but with the ing of Babylon, one based on the Babylonian ideol- ideological notions that the monuments conveyed to ogy of the city's role in the universe rather than the ancient viewer. -

Life and Society in the Hittite World .~•

Life and Society in the Hittite World .~•. TREVOR BRYCE OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS ~ ! [tI ~. <: cr"e:; B: ,..,61 ~~ , "- ~'O 0" ~ ~(j~~0. 0 (") _. ,;g'" ::>-0 0. 'O~.'" - ~ ;; ~ ~~ ~ '" _·ca Ul p.;. '" 0'"1""0 .., "-< ..., o..p,)(p=: (1) c,:.-.,\b ::> '" " OJ '" 0 "''0 o· ;. '0'0 s- ~ ~ s· '0..., 1JQ ~ .....,..,~ 3 ~ ." 7: 0 ><_. 3- . _.0 ~ ::l ~ __ 3 OJ QQ~{i" OJ ~ t'" 0. c; ~. aug o.rn ::to 2 '"0 0. -.0'" -2., 2.':<! 0- ~ C 2:. -,0 if> o ::> ~ (1) -.<' ""1:_. =.OJ B. OJ'" ::> '" C 0...., ~ ~ 0. ~. !!. -'QQ ~ '7i ::t 0.::0 c: '" S' N 2:.", ,z'" '"tl, ~ \C '< ~(i 00 ::> 1" QQ r::r R if> ... (1) ~ OJ :..> (1) n VI ;>;" !;l:) """I ... c; '< '" ~ 0 0 :e " 0 ,z (1) '8, ::0 R Vi'- 0\ VI ::> 3' '0 0 ~ 'f B I a c k Sea o ~Mediterranean Sea SYRIAN DESERT o 200km Babylon\. Map r. The World of the Hittites Introduction Some 28 kilometres east of the city of Izmir on Turkey's western coast, there is a mountain pass called Karabel. Overlooking the pass ~ ~~ .:. is a relief cut in the face of the rock. It depicts a male human figure <> /6 armed with bow and spear, and sword with crescent-shaped ~r f) ?> j <l.) OJ) pommel. On his head is a tall peaked cap. A weathered inscrip ] '9 r;: ~.E <: tion provides information about him-for those able to read it. - i.( /~ <l.) N Herodotos visited the monument in the fifth century Be. He des ~ .\,'11'> \. i" =o .... cribes it in his Histories and provides a translation of the inscription i"-sS'4.;&«' Q':l \ E which, he declares, is written in the sacred script of Egypt: 'With my l . -

![The Akkadian Empire /Əˈkeɪdiən/[2] Was an Empire Centered in the City](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9306/the-akkadian-empire-ke-di-n-2-was-an-empire-centered-in-the-city-5259306.webp)

The Akkadian Empire /Əˈkeɪdiən/[2] Was an Empire Centered in the City

Akkad The Akkadian Empire /əˈkeɪdiən/[2] was an empire centered in the city of Akkad /ˈækæd/[3] and its surrounding region in ancient Mesopotamia which united all the indigenous Akkadian speakingSemites and the Sumerian speakers under one rule.[4] During the 3rd millennium BC, there developed a very intimate cultural symbiosis between the Sumerians and the Semitic Akkadians, which included widespread bilingualism.[5] Akkadian gradually replaced Sumerian as a spoken language somewhere around the turn of the 3rd and the 2nd millennium BC (the exact dating being a matter of debate).[6] The Akkadian Empire reached its political peak between the 24th and 22nd centuries BC, following the conquests by its founder Sargon of Akkad (2334–2279 BC). Under Sargon and his successors, Akkadian language was briefly imposed on neighboring conquered states such as Elam. Akkad is sometimes regarded as the first empire in history,[7] though there are earlier Sumerian claimants.[8] After the fall of the Akkadian Empire, the Akkadian peoples of Mesopotamia eventually coalesced into two major Akkadian speaking nations; Assyria in the north, and a few centuries later,Babylonia in the south. Contents [hide] 1 City of Akkad 2 History o 2.1 Origins . 2.1.1 Sargon and his sons . 2.1.2 Naram-Sin o 2.2 Collapse of the Akkadian Empire o 2.3 The Curse 3 Government 4 Economy 5 Culture o 5.1 Language o 5.2 Poet – priestess Enheduanna o 5.3 Technology o 5.4 Achievements 6 See also 7 Notes 8 Further reading 9 External links 1 City of Akkad Main article: Akkad (city) The precise archaeological site of the city of Akkad has not yet been found.[9] The form Agade appears in Sumerian, for example in the Sumerian King List; the later Assyro-Babylonian form Akkadû ("of or belonging to Akkad") was likely derived from this. -

Poetry and War Among the Hittites Mark Weeden

CHAPTER 3 Poetry and War among the Hittites Mark Weeden WHO WERE THE HITTITES? During the nineteenth century European visitors to central Anatolia came upon the ruins of a large ancient city near the village of Bo!azköy, modern-day Bo!azkale. Already during the initial period of investigation that ensued over the next 50 years, links were made with Iron Age (first millennium bc) inscriptions in an as yet undeciphered hieroglyphic script that were known from northern Syria, and the people known to readers of the Hebrew Bible as the Hittites. As it turned out, these indirectly related phenomena were separated by several hundred years from the Late Bronze Age (c.1600–1200 bc) civilisation that had its seat at Bo!azköy.1 At the beginning of the twentieth century joint German and Turkish exca- vations at this site brought to light thousands of clay tablets inscribed with the cuneiform script, many in Akkadian, the lingua franca of the Ancient Near East in the Late Bronze Age, but many others in a language that bore resemblance to an Indo-European dialect already known from two letters found in the cuneiform archive from Amarna, Egypt. The Akkadian docu- ments, especially treaties with the great powers of the time, soon made it clear that this was the ancient city of Hattusa, capital of the Hittite Empire. By 1917 the language, known to its speakers as Nesili (the language of Nesa), was officially deciphered and became known to the modern world as Hittite, the oldest attested member of the Indo-European language family.2 Excavations continue at the site to this day, and the number of cuneiform tablets and fragments recovered thus far amounts to some 30,0003.