The Danes, the European Union and the Forthcoming Presidency

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tirsdag Den 28. Marts 2000 5661 Meddelelser

Tirsdag den 28. marts 2000 5661 Meddelelser fra formanden Forslag til folketingsbeslutning om legitima- tionskort til alle i ældreplejen. Formanden: (Beslutningsforslag nr. B 133). Fra midlertidigt medlem af Folketinget Ulrik Kragh har jeg modtaget meddelelse om, at han Medlemmer af Folketinget Jørn Jespersen (SF), fra og med dags dato ikke ser sig i stand til at Jes Lunde (SF) og Ole Sohn (SF) har meddelt fortsætte som stedfortræder tinder medlem af mig, at de ønsker at stille følgende forespørgsel Folketinget Anders Mølgaards orlov. til erhvervsministeren: Medlem af Folketinget Frank Dahlgaard (UP) »Hvad kan ministeren oplyse om regeringens har meddelt mig, at han ønsker skriftligt at planer for at styrke ledelsesindsatsen i danske fremsætte: virksomheder og offentlige institutioner med henblik på at styrke dansk økonomis effektivitet Forslag til folketingsbeslutning om forbud mod og omstillingsevne, fremme kvaliteten af den udsendelse af porno på ukodede, betalingsfri offentlige sektors velfærdsydelser og øge med- tv-kanalér. arbejdemes indflydelse på egne arbejdsvilkår (Beslutningsforslag nr. B 129). og arbejdspladsens overordnede udvikling?« (Forespørgsel nr. F 48). Forslag til folketingsbeslutning om en hus- standsomdelt informationsavis om kronens af- skaffelse til fordel for euroen. (Beslutningsforslag nr. B 130). Medlemmer af Folketinget Brian Mikkelsen Den første sag på dagsordenen var: (KF) og Knud Erik Kirkegaard (KF) har meddelt 1) Indstilling fra Udvalget til Valgs Prøvelse. mig, at de ønsker skriftligt at fremsætte: (Godkendelse af ny stedfortræder for Anders Mølgaard (V)). Forslag til folketingsbeslutning om oprettelse af en ny, institutionsuafhængig uddannelses- og Formanden: erhvervsvejledning. Efter at 1. stedfortræder Ulrik Kragh som nævnt (Beslutningsforslag nr. B 131). har meddelt, at han ikke ser sig i stand til at fortsætte som stedfortræder under Anders Medlemmer af Folketinget Villy Søvndal (SF), Mølgaards orlov, har jeg fra Udvalget til Valgs Anne Baastrup (SF), Jes Lunde (SF) og Prøvelse modtaget indstilling om, at 2. -

Codebook Indiveu – Party Preferences

Codebook InDivEU – party preferences European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies December 2020 Introduction The “InDivEU – party preferences” dataset provides data on the positions of more than 400 parties from 28 countries1 on questions of (differentiated) European integration. The dataset comprises a selection of party positions taken from two existing datasets: (1) The EU Profiler/euandi Trend File The EU Profiler/euandi Trend File contains party positions for three rounds of European Parliament elections (2009, 2014, and 2019). Party positions were determined in an iterative process of party self-placement and expert judgement. For more information: https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/65944 (2) The Chapel Hill Expert Survey The Chapel Hill Expert Survey contains party positions for the national elections most closely corresponding the European Parliament elections of 2009, 2014, 2019. Party positions were determined by expert judgement. For more information: https://www.chesdata.eu/ Three additional party positions, related to DI-specific questions, are included in the dataset. These positions were determined by experts involved in the 2019 edition of euandi after the elections took place. The inclusion of party positions in the “InDivEU – party preferences” is limited to the following issues: - General questions about the EU - Questions about EU policy - Questions about differentiated integration - Questions about party ideology 1 This includes all 27 member states of the European Union in 2020, plus the United Kingdom. How to Cite When using the ‘InDivEU – Party Preferences’ dataset, please cite all of the following three articles: 1. Reiljan, Andres, Frederico Ferreira da Silva, Lorenzo Cicchi, Diego Garzia, Alexander H. -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

The Growth of the Radical Right in Nordic Countries: Observations from the Past 20 Years

THE GROWTH OF THE RADICAL RIGHT IN NORDIC COUNTRIES: OBSERVATIONS FROM THE PAST 20 YEARS By Anders Widfeldt TRANSATLANTIC COUNCIL ON MIGRATION THE GROWTH OF THE RADICAL RIGHT IN NORDIC COUNTRIES: Observations from the Past 20 Years By Anders Widfeldt June 2018 Acknowledgments This research was commissioned for the eighteenth plenary meeting of the Transatlantic Council on Migration, an initiative of the Migration Policy Institute (MPI), held in Stockholm in November 2017. The meeting’s theme was “The Future of Migration Policy in a Volatile Political Landscape,” and this report was one of several that informed the Council’s discussions. The Council is a unique deliberative body that examines vital policy issues and informs migration policymaking processes in North America and Europe. The Council’s work is generously supported by the following foundations and governments: the Open Society Foundations, Carnegie Corporation of New York, the Barrow Cadbury Trust, the Luso- American Development Foundation, the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, and the governments of Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden. For more on the Transatlantic Council on Migration, please visit: www.migrationpolicy.org/ transatlantic. © 2018 Migration Policy Institute. All Rights Reserved. Cover Design: April Siruno, MPI Layout: Sara Staedicke, MPI No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Migration Policy Institute. A full-text PDF of this document is available for free download from www.migrationpolicy.org. Information for reproducing excerpts from this report can be found at www.migrationpolicy.org/about/copyright-policy. -

Det Offentlige Danmark 2018 © Digitaliseringsstyrelsen, 2018

Det offentlige Danmark 2018 © Digitaliseringsstyrelsen, 2018 Udgiver: Finansministeriet Redaktion: Digitaliseringsstyrelsen Opsætning og layout: Rosendahls a/s ISBN 978-87-93073-23-4 ISSN 2446-4589 Det offentlige Danmark 2018 Oversigt over indretningen af den offentlige sektor Om publikationen Den første statshåndbog i Danmark udkom på tysk i Oversigt over de enkelte regeringer siden 1848 1734. Fra 1801 udkom en dansk udgave med vekslende Frem til seneste grundlovsændring i 1953 er udelukkende udgivere. Fra 1918 til 1926 blev den udgivet af Kabinets- regeringscheferne nævnt. Fra 1953 er alle ministre nævnt sekretariatet og Indenrigsministeriet og derefter af Kabi- med partibetegnelser. netssekretariatet og Statsministeriet. Udgivelsen Hof & Stat udkom sidste gang i 2013 i fuld version. Det er siden besluttet, at der etableres en oversigt over indretningen Person- og realregister af den offentlige sektor ved nærværende publikation, Der er ikke udarbejdet et person- og realregister til som udkom første gang i 2017. Det offentlige Danmark denne publikation. Ønsker man at fremfnde en bestem indeholder således en opgørelse over centrale instituti- person eller institution, henvises der til søgefunktionen oner i den offentlige sektor i Danmark, samt hvem der (Ctrl + f). leder disse. Hofdelen af den tidligere Hof- og Statskalen- der varetages af Kabinetssekretariatet, som stiller infor- mationer om Kongehuset til rådighed på Kongehusets Redaktionen hjemmeside. Indholdet til publikationen er indsamlet i første halvår 2018. Myndighederne er blevet -

Lyngallup: Vurdering Af Ministre 2012

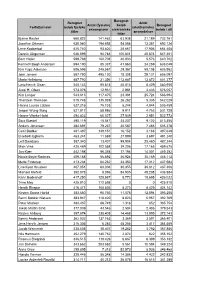

Lyngallup: Vurdering af ministre 2012 Lyngallup: Vurdering af ministre 2012 © TNS Dato: 12. december 2012 Projekt:58974 Vurdering af ministre 2012 Feltperiode: Den 7.-12. december 2012 Målgruppe: Repræsentativt udvalgte vælgere landet over på 18 eller derover Metode: GallupForum (webinterviews) Stikprøvestørrelse: 1.012 personer Stikprøven er vejet på køn, alder, region, uddannelse og partivalg ved FV11 Akkreditering: Enhver offentliggørelse af resultater, der stammer fra denne undersøgelse, skal være anført følgende kildeangivelse: © TNS Gallup for BT © TNS Gallup for BT Gallups undersøgelse er gennemført d. 7.-12. december 2012 og er baseret på GallupForum webinterview med 1.012 repræsentativt udvalgte vælgere landet over på 18 år eller derover. Lyngallup: Vurdering af ministre 2012 © TNS Dato: 12. december 2012 Projekt:58974 2 Vurdering af ministre 2012 Sammenfatning: De 5 mest synlige ministre i 2012 er: Helle Thorning-Schmidt 56%, Margrethe Vestager 50%, Bjarne Corydon 50%, Mette Frederiksen 32% og Villy Søvndal 30%. De 5 mest fagligt kompetente ministre i 2012 er: Margrethe Vestager 36%, Bjarne Corydon 29%, Mette Frederiksen 19%, Helle Thorning-Schmidt 17% og Marianne Jelved 17%. De 5 mest visionære ministre i 2012 er: Ida Auken 19%, Christine Antorini 17%, Margrethe Vestager 17%, Bjarne Corydon 13% og Mette Frederiksen 12%. Rangeringen af ministre, der er gode til at få deres politik gennemført er således: Margrethe Vestager 42%, Bjarne Corydon 29%, Mette Frederiksen 13%, Christine Antorini 12% og Helle Thorning-Schmidt 8%. På listen over de 5 ministre, der er bedst til at tiltrække nye vælgere finder vi: Margrethe Vestager 26%, Ida Auken 14%, Mette Frederiksen 14%, Annette Vilhelmsen 10%, Bjarne Corydon 9%. -

Rating Af Politisk Lederskab: Jelved - Gammeldags Og Topmoderne

nr.30side20-24.qxd 05-09-2003 17:08 Side 20 Mandagmorgen Politik Rating af politisk lederskab: Jelved - gammeldags og topmoderne Karakterbog. Marianne Jelved matcher Lykketoft og Fogh - Adskiller sig dog markant fra andre toppoliti- kere - Slår dem alle i ærlighed, integritet og emotionel intelligens - Men kunne blive bedre til kommunika- tion - Samlet set tegner hun fremtidens politiske lederskab - Et meget stærkt brand Hun er lige fyldt 60 år, men alligevel tegner hun frem- Om rating af politisk lederskab tiden i dansk politik. I en tid, hvor lederne af landets to Ugebrevets ratingmodel tager sigte mod at rate politi- største partier først og fremmest er optaget af ikke at ske ledere. Modellen er baseret på otte kategorier. støde vælgere fra sig, får den radikale leder, Marianne Under hver kategori er der formuleret et antal spørgs- Jelved, masser af credit for at have sine meningers mål, som et ratingpanel har udfyldt med en karakter mod, for at turde stille de svære spørgsmål og for at fra 13-skalaen. Politikerens samlede rating fremkom- mer ved, at Ugebrevet sammenlægger resultaterne af turde være sig selv. gennemsnittet fra hver af de otte kategorier. Den radikale leder, der sammen med resten af sit • Ratingpanelet består af 48 omhyggeligt udvalgte parti holder landsmøde på Hotel Nyborg Strand i den personer, der alle har stor indsigt i dansk toppolitik kommende weekend, får gennemsnitligt lige så flotte og toppolitikeres rolle i samfundsudviklingen. Pane- karakterer som Mogens Lykketoft og Anders Fogh let er sammensat politisk afbalanceret. Rasmussen, men på de variable, der er nogle af de vig- • For at sikre en bred og kvalificeret rekruttering har Ugebrevet garanteret panelet anonymitet. -

Betænkning Over Forslag Til Folketingsbeslutning Om Større Statslig Medfinansiering Af Kunstakademierne I Aarhus Og Odense

Udskriftsdato: 1. oktober 2021 2017/1 BTB 70 (Gældende) Betænkning over Forslag til folketingsbeslutning om større statslig medfinansiering af kunstakademierne i Aarhus og Odense Ministerium: Folketinget Betænkning afgivet af Kulturudvalget den 9. maj 2018 Betænkning over Forslag til folketingsbeslutning om større statslig medfinansiering af kunstakademierne i Aarhus og Odense [af Alex Ahrendtsen (DF) m.fl.] 1. Udvalgsarbejdet Beslutningsforslaget blev fremsat den 1. februar 2018 og var til 1. behandling den 2. marts 2018. Be slutningsforslaget blev efter 1. behandling henvist til behandling i Kulturudvalget. Møder Udvalget har behandlet beslutningsforslaget i 2 møder. 2. Indstillinger og politiske bemærkninger Et flertal i udvalget (udvalget med undtagelse af DF) indstiller beslutningsforslaget til forkastelse. Enhedslistens medlemmer af udvalget kan ikke støtte forslaget. Ved førstebehandlingen af forslaget efterlyste Enhedslisten nogle begrundelser for forslaget – ud over ønsket om at overføre penge fra kunstakademiet i København til kunstakademierne i Aarhus og Odense. Samtidig efterlyste Enhedslisten forslagsstillernes analyse af, hvad konsekvenserne af forslaget ville blive for den samlede kunstakade miuddannelse i Danmark. Desværre fremlagde forslagsstillerne hverken disse begrundelser/analyser under førstebehandlingen eller i forbindelse med udvalgsbehandlingen. Et mindretal i udvalget (DF) indstiller lovforslaget til vedtagelse. Inuit Ataqatigiit, Nunatta Qitornai, Tjóðveldi og Javnaðarflokkurin var på tidspunktet for betænknin -

Økonomisk-Politisk Kalender 2014

Økonomisk-politisk kalender Økonomisk-politisk kalender 15. apr. Bankunion i EU Europa-Parlamentet godkender EU’s bankunion, som skal Den økonomisk-politiske kalender for perioden primo omfatte alle lande, der har euro. Lande som Danmark, der 2014 og frem indeholder en summarisk oversigt over ikke er en del af eurozonen, skal bestemme sig for, om de vil vigtige økonomiske og politiske begivenheder og be- være en del af den. Den nye bankunion skal føre overordnet slutninger. Anmærkningerne anført i parentes fx (L 209) tilsyn med samtlige banker i bankunionen og direkte tilsyn henviser til Folketingets nummerering af lovforslag. med de 130 største. Over 8 år skal opbygges en fond med 410 mia. euro indbetalt af bankerne selv til at betale for afvikling af banker. Bankunionen træder i kraft til novem- 2014 ber. 30. jan. SF træder ud af regeringen 21. mar. Rusland annekterer Krim Socialistisk Folkeparti trækker sig fra S-R-SF-regeringen, og Rusland annekterer formelt Krim efter en folkeafstemning partiformand Anette Vilhelmsen går af som partiformand. afholdt 16. marts om løsrivelse og tilslutning til Rusland. 92 Beslutningen træffes på et gruppemøde kort før en afstem- pct. svarede ja ved folkeafstemningen. Vesten anerkender ning om et beslutningsforslag i Folketinget, som har til ikke den russiske overtagelse af Krim. EU og USA har indført hensigt at udsætte salget af Dong-aktier til den amerikanske sanktioner mod Rusland. investeringsbank Goldman Sachs. Udsættelsen bliver ikke vedtaget. 14. maj Metroen udbygges for 8,4 mia. kr. SR-regeringen og Københavns Kommune har indgået aftale 3. feb. Regeringen Helle Thorning-Schmidt II om at udbygge den Københavnske metro for i alt 8,6 mio. -

Right-Wing Extremism in Europe I Ii Right-Wing Extremism in Europe Right-Wing Extremism

Ralf Melzer, Sebastian Serafin (Eds.) RIGHT-WING EXTREMISM IN EUROPE Country Analyses, Counter-Strategies and Labor-Market Oriented Exit Strategies COUNTRY ANALYSES SWEDEN FES GEGEN RECHTS EXTREMISMUS Forum Berlin RIGHT-WING EXTREMISM IN EUROPE I II RIGHT-WING EXTREMISM IN EUROPE RIGHT-WING EXTREMISM IN EUROPE Country Analyses, Counter-Strategies and Labor-Market Oriented Exit Strategies COUNTRY ANALYSES SWEDEN n Ralf Melzer, Sebastian Serafi (Eds.) ISBN: 978-3-86498-940-7 Friedrich-Ebert-StiftungEdited for: by Ralf Melzer(Friedrich and SebastianEbert Foundation) Serafin “Project on Combatting Right-Wing Extremism” Forum Berlin/Politischer Dialog Hiroshimastraße 17, 10785 Berlin Sandra Hinchman, Lewis Hinchman Proofreading: zappmedia GmbH,Translations: Berlin Pellens Kommunikationsdesigndpa PictureGmbH, Alliance BonnPhotos: Design: Projekt „GegenCopyright Rechtsextremismus“, 2014 by Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Forum Berlin RIGHT-WINGThe spelling, grammar, and other linguistic conventions in this publication reflect The judgments and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author. They do not necessarily represent the views of the Friedrich Ebert Foundation or of the editors. This publication was compiled as part of a project entitled “Confronting right-wing extremism Editors’ notes: by developing networks of exit-oriented assistance.” That project, in turn, is integral to the American English usage. XENOS special program known as “exit to enter” which has received grants from both the EXTREMISMGerman Federal Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs and the European Social Fund. IN CountryEUROPE analyses, Counter-strategies and labour-market oriented Exit-strategies RECHTSEXTREMISMUS IN EUROPA IN RECHTSEXTREMISMUS ISBN: 978 - 3 - 86498 - 522 - 5 S FE GEGEN S RECHT S Forum Berlin MISMU EXTRE Inhalt 1. Introduction .............................................................................................. -

Se Samlet Liste Over Modtagere I 2020

Beregnet Beregnet Antal Antal (fysiske) beløb Beregnet Forfatternavn beløb fysiske (elektroniske) eksemplarer elekroniske beløb i alt titler anvendelser titler Bjarne Reuter 668.822 141.462 63.938 21.189 732.761 Josefine Ottesen 638.040 194.693 54.084 13.381 692.124 Lene Kaaberbøl 625.740 93.802 28.667 17.906 654.408 Dennis Jürgensen 546.599 94.784 100.801 20.674 647.401 Bent Haller 599.769 160.708 40.933 5.576 640.702 Kenneth Bøgh Andersen 594.190 85.337 41.860 24.259 636.049 Kim Fupz Aakeson 606.596 246.567 29.367 58.108 635.962 Jørn Jensen 587.790 495.130 18.308 29.131 606.097 Maria Helleberg 487.790 31.356 113.487 13.872 601.277 Lars-Henrik Olsen 540.143 95.818 40.813 8.429 580.956 Jussi H. Olsen 573.076 12.931 2.981 3.433 576.057 Kim Langer 543.613 117.475 23.381 25.724 566.994 Thorstein Thomsen 515.748 135.939 26.282 5.335 542.029 Hanna Louisa Lützen 527.216 75.133 8.244 4.844 535.459 Jesper Wung-Sung 521.817 58.986 9.911 4.753 531.728 Hanne-Vibeke Holst 494.823 60.027 27.949 2.951 522.773 Sara Blædel 490.119 15.047 23.237 9.122 513.356 Anders Johansen 484.691 79.237 20.587 7.465 505.278 Cecil Bødker 481.497 139.151 16.152 3.188 497.649 Elsebeth Egholm 463.241 11.869 27.999 3.697 491.240 Leif Davidsen 387.340 13.407 99.904 20.460 487.244 Mich Vraa 420.469 102.558 39.206 17.165 459.675 Jan Kjær 442.198 96.358 17.194 14.001 459.392 Nicole Boyle Rødtnes 409.188 56.692 36.924 35.169 446.112 Mette Finderup 413.234 64.262 24.350 17.312 437.584 Line Kyed Knudsen 407.051 68.304 30.355 36.812 437.406 Michael Krefeld 352.078 8.096 84.905 -

The Bureau of the Congress Verification of New Members

The Bureau of the Congress CG/BUR18(2018)131 19 March 2018 Verification of new members’ credentials Co-rapporteurs:2 Michail ANGELOPOULOS, Greece (L, EPP/CCE) Eunice CAMPBELL-CLARK, United Kingdom (R, SOC) Preliminary draft resolution .......................................................................................................................... 2 Summary The rapporteurs review the credentials of the new members in the light of the current criteria of the Congress Charter and Rules and Procedures. Document submitted for approval to the Bureau of the Congress on 26 March 2018 1 This document is classified confidential until it has been examined by the Bureau of the Congress. 2 L: Chamber of Local Authorities / R: Chamber of Regions EPP/CCE: European People’s Party Group in the Congress SOC: Socialist Group ILDG: Independent and Liberal Democrat Group ECR: European Conservatives and Reformists Group NR: Members not belonging to a political group of the Congress Tel ► +33 (0)3 8841 2110 Fax ► +33 (0)3 8841 2719 [email protected] CG/BUR18(2018)13 PRELIMINARY DRAFT RESOLUTION 1. In compliance with the Congress’ Charter and Rules and Procedures, the countries listed hereafter have changed the composition of their delegation due to either the loss of mandate or the resignation of some members of the delegation: Armenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Georgia, Ireland, Latvia, Montenegro, Norway, Romania, Spain, Sweden, “The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia”, United Kingdom. 2. At present there are 5 representative seats and 11 substitute seats vacant out of a total of 648 seats. The countries concerned – Germany, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, France, Italy, Poland and Romania – are invited to complete their delegation.