What Is a Boggart Hole?1 Simon Young ISI, Florence (Italy)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix 5 Fylde

FYLDE DISTRICT - APPENDIX 5 SUBSIDISED LOCAL BUS SERVICE EVENING AND SUNDAY JOURNEYS PROPOSED TO BE WITHDRAWN FROM 18 MAY 2014 LANCASTER - GARSTANG - POULTON - BLACKPOOL 42 via Galgate - Great Eccleston MONDAY TO SATURDAY Service Number 42 42 42 $ $ $ LANCASTER Bus Station 1900 2015 2130 SCOTFORTH Boot and Shoe 1909 2024 2139 LANCASTER University Gates 1912 2027 2142 GALGATE Crossroads 1915 2030 2145 CABUS Hamilton Arms 1921 2036 2151 GARSTANG Bridge Street 1926 2041 2156 CHURCHTOWN Horns Inn 1935 2050 2205 ST MICHAELS Grapes Hotel 1939 2054 2209 GREAT ECCLESTON Square 1943 2058 2213 POULTON St Chads Church 1953 2108 2223 BLACKPOOL Layton Square 1958 2113 2228 BLACKPOOL Abingdon Street 2010 2125 2240 $ - Operated on behalf of Lancashire County Council BLACKPOOL - POULTON - GARSTANG - LANCASTER 42 via Great Eccleston - Galgate MONDAY TO SATURDAY Service Number 42 42 42 $ $ $ BLACKPOOL Abingdon Street 2015 2130 2245 BLACKPOOL Layton Square 2020 2135 2250 POULTON Teanlowe Centre 2032 2147 2302 GREAT ECCLESTON Square 2042 2157 2312 ST MICHAELS Grapes Hotel 2047 2202 2317 CHURCHTOWN Horns Inn 2051 2206 2321 GARSTANG Park Hill Road 2059 2214 2329 CABUS Hamilton Arms 2106 2221 2336 GALGATE Crossroads 2112 2227 2342 LANCASTER University Gates 2115 2230 2345 SCOTFORTH Boot and Shoe 2118 2233 2348 LANCASTER Bus Station 2127 2242 2357 $ - Operated on behalf of Lancashire County Council LIST OF ALTERNATIVE TRANSPORT SERVICES AVAILABLE – Stagecoach in Lancaster Service 2 between Lancaster and University Stagecoach in Lancaster Service 40 between Lancaster and Garstang (limited) Blackpool Transport Service 2 between Poulton and Blackpool FYLDE DISTRICT - APPENDIX 5 SUBSIDISED LOCAL BUS SERVICE EVENING AND SUNDAY JOURNEYS PROPOSED TO BE WITHDRAWN FROM 18 MAY 2014 PRESTON - LYTHAM - ST. -

Samuel House, 1St Floor, 5 Fox Valley Way, Stocksbridge, Sheffield, S36 2AA Tel: 0114 321 5151 Our Ref: SHF.1615

Samuel House, 1st Floor, 5 Fox Valley Way, Stocksbridge, Sheffield, S36 2AA Tel: 0114 321 5151 www.enzygo.com Our Ref: SHF.1615.003.HY.L.001.A Date: 13th February 2020 Your Reference: 3/2020/0010 FAO: Carole Woosey Email: [email protected] Ribble Valley Borough Council Development Control Council Offices Church Walk Clitheroe Lancashire BB7 2RA Dear Carole, RE: HENTHORN ROAD, CLITHEROE, BB7 2QF [REFERENCE 3/2020/0010] - RESPONSE TO ENVIRONMENT AGENCY OBJECTION Enzygo Ltd have been commissioned to provide a response to an Environment Agency objection to a reserved matters planning application for 21 units on the above Site. A copy of the Environment Agency objection letter (Reference: NO/2020/112396/01-L01) is included as Attachment 1. This letter relates specifically to addressing Comments 1, 2 and 3 of the Environment Agency response. Please find below our response to the Environment Agency comments. ‘The proposed development would restrict essential maintenance and emergency access to Pendleton Brook, Main River. The permanent retention of a continuous unobstructed area is an essential requirement for future maintenance and/or improvement work’ To overcome our objection, the applicant should; 1) Submit cross sections extending from the water’s edge, including the top of the riverbank to the development areas closest to the watercourse, specifically plots 8 and 13 (Sabden), plot 7 (Eagley) and between the top of the riverbank and the attenuation pond. Drawing HR-BTP-00-S-DR-A-3537_160A (Attachment 2) includes cross sections at Plots 8, 7, 13 and the attenuation basin location as requested. The cross sections demonstrate that the built development will be a minimum of 13.2m (Plot 8) from the surveyed Pendleton Brook right bank top (A). -

Lancaster Archaeological and Historical Society Research Group Newsletter

Lancaster Archaeological and Multum in parvo Historical Society http://lahs.archaeologyuk.org/ Research Group Newsletter orem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetuer adipisci No. 2: August 2020 Welcome to the Research Group e-newsletter We received encouraging feedback from Society amount of research now being conducted online, members following the first issue of the e-newsletter news that the National Archives are allowing people in May 2020 which was much appreciated. The e- to download their digital resources free during the newsletter is open to all Society members and guest pandemic has been very welcome. If you have a authors should they be interested in publishing a brief Lancashire County Library ticket it is possible to letter, or a short article of 500-750 words on an access information online such as the Oxford archaeological or historical subject related to Dictionary of National Biography and several local Lancaster and surrounding areas. Longer articles are papers from the nineteenth century (with thanks to Dr published in Contrebis Michael Winstanley). As lockdown restrictions begin to ease, do not delay in taking advantage when The last five months have been a difficult time for research facilities re-open because with social researchers with the Covid-19 lockdown making distancing measures still in force, there are likely to face-to-face meetings impossible; archive, museum be appointment systems or time-limited visits and library services closed, and employees in many introduced. organisations working from home. Research can be a lonely occupation at the best of times so the surge in If you would like to join the Research Group or online virtual meetings has offered some welcome contribute to the e-newsletter, contact details are relief from social isolation. -

Site 9 Primrose Mill, Clitheroe

Inter Hydro Technology Forest of Bowland AONB Hydro Feasibility Study Site 9: Primrose Mill, Clitheroe Site Assessment Report Title Figure 1 Map showing general layout Primrose Mill is a former water powered cotton spinning mill built in 1787. It later became a print works, paper works and lifting equipment manufacturer. The mill site has been extensively redeveloped and now provides a private residence, and a mix of technology and industrial business occupancy. The millpond lies to the North East on Mearley Brook and is not in the ownership of site however, the owners of the site have water abstraction rights. The weir and intake appear in good condition and the scope to produce energy at this site is good. The option shown above involves the construction of a new inlet and screen at the top of the weir and laying of a buried pipeline passing down the driveway to Primrose Lodge. The pipeline would need to pass under the currently unoccupied part of the mill building. A new powerhouse and new turbine would be constructed adjacent to the Pendleton Brook. A second option worthy of consideration would be to construct a turbine and power house on the weir. However, this may result in increasing flood risk upstream and a flood risk assessment would be required early in the feasibility stage to evaluate the risk. Authors Name Authors Title Date Forest of Bo wland AONB 1 2011 Inter Hydro Technology Forest of Bowland AONB Hydro Feasibility Study Figure 2 Intake weir from downstream Figure 3 Existing intake channel above weir Catchment Analysis Figure 4 Catchment boundary defined by Flood Estimation Handbook Software 2 Forest of Bowland AONB 2011 Inter Hydro Technology Forest of Bowland AONB Hydro Feasibility Study The Flood Estimation Handbook software is used to determine the following catchment descriptors for the proposed intake location, selected during the site visit. -

2005 No. 170 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2005 No. 170 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The County of Lancashire (Electoral Changes) Order 2005 Made - - - - 1st February 2005 Coming into force in accordance with article 1(2) Whereas the Boundary Committee for England(a), acting pursuant to section 15(4) of the Local Government Act 1992(b), has submitted to the Electoral Commission(c) recommendations dated October 2004 on its review of the county of Lancashire: And whereas the Electoral Commission have decided to give effect, with modifications, to those recommendations: And whereas a period of not less than six weeks has expired since the receipt of those recommendations: Now, therefore, the Electoral Commission, in exercise of the powers conferred on them by sections 17(d) and 26(e) of the Local Government Act 1992, and of all other powers enabling them in that behalf, hereby make the following Order: Citation and commencement 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the County of Lancashire (Electoral Changes) Order 2005. (2) This Order shall come into force – (a) for the purpose of proceedings preliminary or relating to any election to be held on the ordinary day of election of councillors in 2005, on the day after that on which it is made; (b) for all other purposes, on the ordinary day of election of councillors in 2005. Interpretation 2. In this Order – (a) The Boundary Committee for England is a committee of the Electoral Commission, established by the Electoral Commission in accordance with section 14 of the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000 (c.41). The Local Government Commission for England (Transfer of Functions) Order 2001 (S.I. -

Initial Template Document

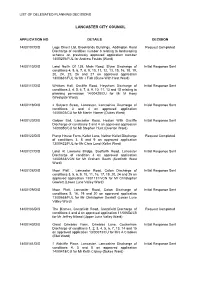

LIST OF DELEGATED PLANNING DECISIONS LANCASTER CITY COUNCIL APPLICATION NO DETAILS DECISION 14/00107/DIS Logs Direct Ltd, Brooklands Buildings, Addington Road Request Completed Discharge of condition number 6 relating to landscaping scheme on previously approved application number 14/00276/FUL for Andrew Foulds (Ward) 14/00110/DIS Land North Of 138, Main Road, Slyne Discharge of Initial Response Sent conditions 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 15, 16, 18, 19, 20, 24, 25, 26 and 27 on approved application 13/00831/FUL for Mr J Fish (Slyne With Hest Ward) 14/00117/DIS Whittam Hall, Oxcliffe Road, Heysham Discharge of Initial Response Sent conditions 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13 and 15 relating to planning permission 14/00428/CU for Mr M Hoey (Westgate Ward) 14/00119/DIS 2 Sulyard Street, Lancaster, Lancashire Discharge of Initial Response Sent conditions 3 and 4 on approved application 14/00403/CU for Mr Martin Horner (Dukes Ward) 14/00120/DIS Golden Ball, Lancaster Road, Heaton With Oxcliffe Initial Response Sent Discharge of conditions 3 and 4 on approved application 14/00050/CU for Mr Stephen Hunt (Overton Ward) 14/00122/DIS Pump House Farm, Kellet Lane, Nether Kellet Discharge Request Completed of conditions 3, 8 and 9 on approved application 13/00422/FUL for Mr Chris Lund (Kellet Ward) 14/00127/DIS Land At Lawsons Bridge, Scotforth Road, Lancaster Initial Response Sent Discharge of condition 4 on approved application 14/00633/VCN for Mr Graham Booth (Scotforth West Ward) 14/00128/DIS Moor Platt , Lancaster Road, Caton Discharge -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G. Phd, Mphil, Dclinpsychol) at the University of Edinburgh

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Desire for Perpetuation: Fairy Writing and Re-creation of National Identity in the Narratives of Walter Scott, John Black, James Hogg and Andrew Lang Yuki Yoshino A Thesis Submitted to The University of Edinburgh for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English Literature 2013 Abstract This thesis argues that ‘fairy writing’ in the nineteenth-century Scottish literature serves as a peculiar site which accommodates various, often ambiguous and subversive, responses to the processes of constructing new national identities occurring in, and outwith, post-union Scotland. It contends that a pathetic sense of loss, emptiness and absence, together with strong preoccupations with the land, and a desire to perpetuate the nation which has become state-less, commonly underpin the wide variety of fairy writings by Walter Scott, John Black, James Hogg and Andrew Lang. -

Environment Agency North West Region Central Area

Central area redd project [Ribble, Hodder and Lune catchments] Item Type monograph Authors Lewis, J. Publisher Environment Agency North West Download date 02/10/2021 20:24:19 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/25128 ENVIRONMENT AGENCY NORTH WEST REGION CENTRAL AREA REDD PROJECT J LEWIS FEBRUARY 2000 G:\FER\Fisheries\Redd Counts\GIS Data Central Area Fisheries Science and Management Team Redd Distribution Project SUMMARY Redd counting is an integral part of most Fishery Officers duties. The number and distribution of salmonid redds throughout salmonid catchments provides invaluable information on the range and extent of spawning by both salmon and sea trout. A project was initiated by the Fisheries Science and Management Team of Central Area, NW Region in liason with the Flood Defence function. The main objective of this project was to assess redd count data for Central Area and attempt to quantify these data in order to produce a grading system that would highlight key salmonid spawning areas. By showing which were the main areas for salmon and sea trout spawning, better informed decisions could be made on whether or not in-stream Flood Defence works should be given the go-ahead. The main salmonid catchments in Central Area were broken into individual reaches, approximately 1 km in length. The number of redds in these individual reaches were then calculated and a density per lkm value was obtained for each reach. A grading system was devised which involved looking at the range of density per km values and dividing this by five to produce 5 classes, A - E. -

Authority Monitoring Report 6

Monitoring Report Part of the Blackburn with Darwen Local Development Framework 6 December 2010 Blackburn with Darwen Annual Monitoring Report 6 – 2009-2010 PLANNING ANNUAL MONITORING REPORT December 2010 Blackburn with Darwen Annual Monitoring Report 6 – 2009-2010 CONTENTS PAGE Executive Summary 2 1. Introduction 3 2. Local Development Scheme: Milestones 4 3. An Introduction to Blackburn with Darwen 6 4. Economy 10 5. Housing 17 6. Protecting and enhancing the environment 27 7. Quality of place 34 8. Access to jobs and services 38 9. Monitoring the Borough’s Supplementary Planning Documents 50 10. References 59 11. Glossary 60 Appendix I: Development on Allocated Town Centre Sites 63 Appendix II: Priority Habitats and Species 65 Appendix III: Policies to be retained/superseded from the Blackburn with Darwen Borough Local Plan 66 1 Blackburn with Darwen Annual Monitoring Report 6 – 2009-2010 Executive Summary This is the sixth Annual Monitoring Report for Blackburn with Darwen and includes monitoring information covering the period 1st April 2009 - 31st March 2010. The Local Development Framework, which will eventually replace the current adopted Local Plan is still in the development stage and as a result there are areas where monitoring of this is not possible. The report is, however, as comprehensive as is possible at this point and provides a ‘snap- shot’ of the borough. The monitoring has been completed using a set of indicators – Contextual, Core Output, Local Output and Significant Effect indicators. The Core Output Indicators used in the monitoring report are those set by Government and will ensure consistent monitoring data is produced each year. -

Folklore Creatures BANSHEE: Scotland and Ireland

Folklore creatures BANSHEE: Scotland and ireland • Known as CAOINEAG (wailing woman) • Foretells DEATH, known as messenger from Otherworld • Begins to wail if someone is about to die • In Scottish Gaelic mythology, she is known as the bean sìth or bean-nighe and is seen washing the bloodstained clothes or armor of those who are about to die BANSHEE Doppelganger: GERMANY • Look-alike or double of a living person • Omen of bad luck to come Doppelganger Goblin: France • An evil or mischievous creature, often depicted in a grotesque manner • Known to be playful, but also evil and their tricks could seriously harm people • Greedy and love money and wealth Goblin Black Dog: British Isles • A nocturnal apparition, often said to be associated with the Devil or a Hellhound, regarded as a portent of death, found in deserted roads • It is generally supposed to be larger than a normal dog, and often has large, glowing eyes, moves in silence • Causes despair to those who see it… Black Dog Sea Witch: Great Britain • Phantom or ghost of the dead • Has supernatural powers to control fate of men and their ships at sea (likes to dash ships upon the rocks) The Lay Of The Sea Witch In the waters darkness hides Sea Witch Beneath sky and sun and golden tides In the cold water it abides Above, below, and on all sides In the Shadows she lives Without love or life to give Her heart is withered, black, dried And in the blackness she forever hides Her hair is dark, her skin is silver At her dangerous beauty men shiver But her tongue is sharp as a sliver And at -

Ramblers Gems a Spring Vale Rambling Class Publication

Ramblers Gems A Spring Vale Rambling Class Publication Volume 1, Issue 22 3rd October 2020 For further information or to submit a contribution email: [email protected] Web Site http://www.springvaleramblers.co.uk/ One such example, named ‘Limersgate’ traversed from I N S I D E T H I S I SSUE Haslingden Grane into the Darwen valley, over to Tockholes and on towards Preston. The trail entered 1 A Local Packhorse Trail Darwen at Pickup Bank Heights, and down into Hoddlesden via Long Hey Lane, past Holker House 2 Wordsearch (1591), and over Heys Lane, crossing Roman Road. It 3 Walking in South Lakeland then dropped down Pole Lane to Sough, crossing the River Darwen by a ford at Clough, and climbing to pass 4 Alum Scar White Hall (1557). The trail then dropped into Print 5 Harriers and Falcons Shop crossing Bury Fold and past Kebbs Cottage to Radfield Head, thence into the wooded valley that became Bold Venture Park. A Local Packhorse Trail In the 16th-18th centuries, Darwen was at the crossroads of several packhorse trails that crisscrossed the region. These were narrow, steep and winding, being totally unsuitable for wheeled traffic. Much earlier, the Roman XX (20th) Legion had built a road from Manchester to Ribchester and onward to The Old Bridge at Cadshaw Hadrian’s Wall. However, due to frequent marauding The carters and carriers who oversaw the packhorses attacks by local brigands they constructed few East to and mules, overnighted in Inns at strategic distances West roads. The packhorse trails were developed to enable trains of packhorses and mules, sometimes as along the trails. -

Como SE VA a MPEDIR GALERIA De Los Presidentes Democráticos

como SE VA A MPEDIR GALERIA de los Presidentes Democráticos 4 DE SEPTIEMBRE EDUARDO SALVADOR FREI ALLENDE DOS LIDERES JUNTO AL PUEBLO ESTE DOMINGO CON LA EDICION DE ---F o r t ír=-Diario-----1 SUMARIO e-c¡uc ... ~ ... dobm p..- DIRECTOR Á..u-. Sm anlwp, -... Dinaar ... ha w...... p.. ..pmcb W<:l tal AlaKi6n. ""-_ He· ftaIlt'KO J. Hcm:ros M. lfefOiI .. _1011\'" -... __.... de&midIO P"" .. e...u. FiJcalJa "'.... debido a po-.of_ a la DIRf-CTO R ADJUNTO Fuenas ÑnYdIIenla P'f-.odel FIICllI M,lI!.- Fem.do At.-.roBrioncs R. Tarres S."'.. II rUl!n al aLII ~el el _ de portada de CAUCE N' IboI.li-.Jado JIIIdo al fbcal, EDITOR NACIONAL Hem:tOI fw deIornicIo el ~ por la "'._al lIIe dio de un lI'Ius,Laio y n.endo desplique de del«liwa ErnestO SauJ ....-..do», q... Ioeondoljemn a la Snll Cornll",",a do Inwa EDITOR INTERNACIONAL IiglCiona a ob,e1O do q... P"'"!a.<e decllrKl_ en la l•.inWitker C..... FiK alía t.lIllW. a la qlle ... enoonll"_ ciLado. Lo ED ITOR . :CONOMIA mú ntr""" del c.....elque Herrero . habl. anunciado 111 decisión de ooll1p1l"ecer aaa vector cilación. lo cual e,.. de cunocimierllo pUblico. pu.. wariu r.o<!ioemisor u babian infor EDITOR SOCIEDAD mado al re'P"ClO. Fretly Cancino Elle nceao oficiali.JlI'" poodujo jll5lo en momcnlOSen que el MlJIillCnOdd In· terior anuncilhl elle...mamicruo de loa al'" de ncepción en todo el LaTilnrio nI Rf:[)ACTO RF.5 y cional, alaNrdo 111 ,""""da en función de la tra:uparmcia y garanDII públlC.