The First 40 Years

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heritage Open Days

LANCASTER & MORECAMBE BAY HERITAGE OPEN DAYS 6-9 & 13-16 September 2018 www.heritageopendays.org.uk Heritage Open Days Events 2018 LANCASTER Lancaster Castle Castle Parade, Lancaster, Lancashire, LA1 1YJ Free guided tours of this iconic building recently fully opened to the public. Saturday 8 and Sunday 9 September: Tours run every half an hour from 1000 - 1600. Tours are available on a strictly first come first served basis. Visitors will be given tickets to the next available tour at the time of their arrival - no pre-booking is available for any free tour. Access: We regret that the guided tour is not wheelchair friendly. Contact for the day: 01524 64998 Lancaster Grand Theatre St Leonardgate, Lancaster LA1 1QW Take a tour of this beautiful working theatre which has been continually operating since 1782. Friday 7 September: 1000 to 1530 Saturday 8 September: 1000 to 1530 Sunday 9 September: 1000 to 1530 Access: Certain parts of the theatre only accessible by stairs Max 12 people per tour/session. Tour approx. one hour. No booking required. Contact for the day: Mike Hardy 07771 864385 Lancaster Royal Grammar School East Road, Lancaster, Lancashire, LA1 3EF Visit an exhibition of our famous past pupils and join a guided tour. Saturday 15 September: 1000 - 1600. No booking required. Access: Old School House has steps leading up to the building. Contact for the day: Emma Jones 01524 580632 Lancaster Priory 1 Priory Close, Lancaster, Lancashire, LA1 1YZ Free guided tour and demonstrations of bell ringing in the tower. Saturday 8 September: 1300 – 1600. Tours 1300, 1400 and 1500 Access: The bell tower is not wheelchair accessible. -

National Blood Service-Lancaster

From From Kendal Penrith 006) Slyne M6 A5105 Halton A6 Morecambe B5273 A683 Bare Bare Lane St Royal Lancaster Infirmary Morecambe St J34 Ashton Rd, Lancaster LA1 4RP Torrisholme Tel: 0152 489 6250 Morecambe West End A589 Fax: 0152 489 1196 Bay A589 Skerton A683 A1 Sandylands B5273 A1(M) Lancaster A65 A59 York Castle St M6 A56 Lancaster Blackpool Blackburn Leeds M62 Preston PRODUCED BY BUSINESS MAPS LTD FROM DIGITAL DATA - BARTHOLOMEW(2 M65 Heysham M62 A683 See Inset A1 M61 M180 Heaton M6 Manchester M1 Aldcliffe Liverpool Heysham M60 Port Sheffield A588 e From the M6 Southbound n N Exit the motorway at junction 34 (signed Lancaster, u L Kirkby Lonsdale, Morecambe, Heysham and the A683). r Stodday A6 From the slip road follow all signs to Lancaster. l e Inset t K A6 a t v S in n i Keep in the left hand lane of the one way system. S a g n C R e S m r At third set of traffic lights follow road round to the e t a te u h n s Q r a left. u c h n T La After the car park on the right, the one way system t S bends to the left. A6 t n e Continue over the Lancaster Canal, then turn right at g e Ellel R the roundabout into the Royal Lancaster Infirmary (see d R fe inset). if S cl o d u l t M6 A h B5290 R From the M6 Northbound d Royal d Conder R Exit the motorway at junction 33 (signed Lancaster). -

ALDCLIFFE with STODDAY PARISH COUNCIL

ALDCLIFFE with STODDAY PARISH COUNCIL Minutes of the Meeting held on 1st June 2021 at 7.00pm at the Quaker Meeting House, Lancaster Present: Councillor Nick Webster (Chairman) Councillors Denise Parrett and Duncan Hall. City Councillor Tim Dant Derek Whiteway, Parish Clerk One member of the public attended the meeting 21/032 Apologies for Absence Apologies were received from Councillors Kevan Walton and Chris Norman and from County Councillor Gina Dowding. 21/033 Minutes of the previous meeting 1) The minutes of the Parish Council Annual Meeting held on 4th May 2021, were approved subject to a minor typographical change to minute 21/016(b) – appointment of the Deputy Chair for 2021/22. Matters arising: 2) 21/029(3) – Lengthsman. The Chairman reported that the Lengthsman had cleared the steps leading from leading from the Smuggler’s Lane public footpath onto the estuary multi-use path. The Lengthsman had advised that handrails were not generally installed in such locations, but that alternative options to assist walkers when negotiating the steps would be considered. 21/034 Declarations of Interest No further declarations were made. 21/035 Planning Applications No new planning applications had been referred to the Parish Council since the last meeting. 21/036 Councillors’ Roles The Clerk reported that a request had been received from Scotforth Parish Council inviting Councillors, along with those from Thurnham with Glasson and Ellel Parish Councils, to collaborate in a meeting to discuss issues presented by Bailrigg Garden Village (BGV) developments. Councillors agreed that this would be beneficial and resolved to respond positively to the invitation. -

Lancaster-Cultural-Heritage-Strategy

Page 12 LANCASTER CULTURAL HERITAGE STRATEGY REPORT FOR LANCASTER CITY COUNCIL Page 13 BLUE SAIL LANCASTER CULTURAL HERITAGE STRATEGY MARCH 2011 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...........................................................................3 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................7 2 THE CONTEXT ................................................................................10 3 RECENT VISIONING OF LANCASTER’S CULTURAL HERITAGE 24 4 HOW LANCASTER COMPARES AS A HERITAGE CITY...............28 5 LANCASTER DISTRICT’S BUILT FABRIC .....................................32 6 LANCASTER DISTRICT’S CULTURAL HERITAGE ATTRACTIONS39 7 THE MANAGEMENT OF LANCASTER’S CULTURAL HERITAGE 48 8 THE MARKETING OF LANCASTER’S CULTURAL HERITAGE.....51 9 CONCLUSIONS: SWOT ANALYSIS................................................59 10 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES FOR LANCASTER’S CULTURAL HERITAGE .......................................................................................65 11 INVESTMENT OPTIONS..................................................................67 12 OUR APPROACH TO ASSESSING ECONOMIC IMPACT ..............82 13 TEN YEAR INVESTMENT FRAMEWORK .......................................88 14 ACTION PLAN ...............................................................................107 APPENDICES .......................................................................................108 2 Page 14 BLUE SAIL LANCASTER CULTURAL HERITAGE STRATEGY MARCH 2011 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Lancaster is widely recognised -

The Last Post Reveille

TTHHEE LLAASSTT PPOOSSTT It being the full story of the Lancaster Military Heritage Group War Memorial Project: With a pictorial journey around the local War Memorials With the Presentation of the Books of Honour The D Day and VE 2005 Celebrations The involvement of local Primary School Chidren Commonwealth War Graves in our area Together with RREEVVEEIILLLLEE a Data Disc containing The contents of the 26 Books of Honour The thirty essays written by relatives Other Associated Material (Sold Separately) The Book cover was designed and produced by the pupils from Scotforth St Pauls Primary School, Lancaster working with their artist in residence Carolyn Walker. It was the backdrop to the school's contribution to the "Field of Crosses" project described in Chapter 7 of this book. The whole now forms a permanent Garden of Remembrance in the school playground. The theme of the artwork is: “Remembrance (the poppies), Faith (the Cross) and Hope( the sunlight)”. Published by The Lancaster Military Heritage Group First Published February 2006 Copyright: James Dennis © 2006 ISBN: 0-9551935-0-8 Paperback ISBN: 978-0-95511935-0-7 Paperback Extracts from this Book, and the associated Data Disc, may be copied providing the copies are for individual and personal use only. Religious organisations and Schools may copy and use the information within their own establishments. Otherwise all rights are reserved. No part of this publication and the associated data disc may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the Editor. -

Appendix 5 Fylde

FYLDE DISTRICT - APPENDIX 5 SUBSIDISED LOCAL BUS SERVICE EVENING AND SUNDAY JOURNEYS PROPOSED TO BE WITHDRAWN FROM 18 MAY 2014 LANCASTER - GARSTANG - POULTON - BLACKPOOL 42 via Galgate - Great Eccleston MONDAY TO SATURDAY Service Number 42 42 42 $ $ $ LANCASTER Bus Station 1900 2015 2130 SCOTFORTH Boot and Shoe 1909 2024 2139 LANCASTER University Gates 1912 2027 2142 GALGATE Crossroads 1915 2030 2145 CABUS Hamilton Arms 1921 2036 2151 GARSTANG Bridge Street 1926 2041 2156 CHURCHTOWN Horns Inn 1935 2050 2205 ST MICHAELS Grapes Hotel 1939 2054 2209 GREAT ECCLESTON Square 1943 2058 2213 POULTON St Chads Church 1953 2108 2223 BLACKPOOL Layton Square 1958 2113 2228 BLACKPOOL Abingdon Street 2010 2125 2240 $ - Operated on behalf of Lancashire County Council BLACKPOOL - POULTON - GARSTANG - LANCASTER 42 via Great Eccleston - Galgate MONDAY TO SATURDAY Service Number 42 42 42 $ $ $ BLACKPOOL Abingdon Street 2015 2130 2245 BLACKPOOL Layton Square 2020 2135 2250 POULTON Teanlowe Centre 2032 2147 2302 GREAT ECCLESTON Square 2042 2157 2312 ST MICHAELS Grapes Hotel 2047 2202 2317 CHURCHTOWN Horns Inn 2051 2206 2321 GARSTANG Park Hill Road 2059 2214 2329 CABUS Hamilton Arms 2106 2221 2336 GALGATE Crossroads 2112 2227 2342 LANCASTER University Gates 2115 2230 2345 SCOTFORTH Boot and Shoe 2118 2233 2348 LANCASTER Bus Station 2127 2242 2357 $ - Operated on behalf of Lancashire County Council LIST OF ALTERNATIVE TRANSPORT SERVICES AVAILABLE – Stagecoach in Lancaster Service 2 between Lancaster and University Stagecoach in Lancaster Service 40 between Lancaster and Garstang (limited) Blackpool Transport Service 2 between Poulton and Blackpool FYLDE DISTRICT - APPENDIX 5 SUBSIDISED LOCAL BUS SERVICE EVENING AND SUNDAY JOURNEYS PROPOSED TO BE WITHDRAWN FROM 18 MAY 2014 PRESTON - LYTHAM - ST. -

Lancaster Archaeological and Historical Society Research Group Newsletter

Lancaster Archaeological and Multum in parvo Historical Society http://lahs.archaeologyuk.org/ Research Group Newsletter orem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetuer adipisci No. 2: August 2020 Welcome to the Research Group e-newsletter We received encouraging feedback from Society amount of research now being conducted online, members following the first issue of the e-newsletter news that the National Archives are allowing people in May 2020 which was much appreciated. The e- to download their digital resources free during the newsletter is open to all Society members and guest pandemic has been very welcome. If you have a authors should they be interested in publishing a brief Lancashire County Library ticket it is possible to letter, or a short article of 500-750 words on an access information online such as the Oxford archaeological or historical subject related to Dictionary of National Biography and several local Lancaster and surrounding areas. Longer articles are papers from the nineteenth century (with thanks to Dr published in Contrebis Michael Winstanley). As lockdown restrictions begin to ease, do not delay in taking advantage when The last five months have been a difficult time for research facilities re-open because with social researchers with the Covid-19 lockdown making distancing measures still in force, there are likely to face-to-face meetings impossible; archive, museum be appointment systems or time-limited visits and library services closed, and employees in many introduced. organisations working from home. Research can be a lonely occupation at the best of times so the surge in If you would like to join the Research Group or online virtual meetings has offered some welcome contribute to the e-newsletter, contact details are relief from social isolation. -

The Early History of Man's Activities in the Quernmore Area

I Contrebis 2000 The Early History of Man's Activities in the Quernmore Area. Phil Hudson Introduction This paper hopes to provide a chronological outline of the events which were important in creating the landscape changes in the Quernmore forest area. There was movement into the area by prehistoric man and some further incursions in the Anglo- Saxon and the Norse periods leading to Saxon estates and settled agricultural villages by the time of the Norman Conquest. These villages and estates were taken over by the Normans, and were held of the King, as recorded in Domesday. The Post-Nonnan conquest new lessees made some dramatic changes and later emparked, assarted and enclosed several areas of the forest. This resulted in small estates, farms and vaccaries being founded over the next four hundred years until these enclosed areas were sold off by the Crown putting them into private hands. Finally there was total enclosure of the remaining commons by the 1817 Award. The area around Lancaster and Quernmore appears to have been occupied by man for several thousand years, and there is evidence in the forest landscape of prehistoric and Romano-British occupation sites. These can be seen as relict features and have been mapped as part of my on-going study of the area. (see Maps 1 & 2). Some of this field evidence can be supported by archaeological excavation work, recorded sites and artif.act finds. For prehistoric occupation in the district random finds include: mesolithic flints,l polished stone itxe heads at Heysham;'worked flints at Galgate (SD 4827 5526), Catshaw and Haythomthwaite; stone axe and hammer heads found in Quernmore during the construction of the Thirlmere pipeline c1890;3 a Neolithic bowl, Mortlake type, found in Lancaster,o a Bronze Age boat burial,s at SD 5423 5735: similar date fragments of cinerary urn on Lancaster Moor,6 and several others discovered in Lancaster during building works c1840-1900.7 Several Romano-British sites have been mapped along with finds of rotary quems from the same period and associated artifacts. -

2005 No. 170 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2005 No. 170 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The County of Lancashire (Electoral Changes) Order 2005 Made - - - - 1st February 2005 Coming into force in accordance with article 1(2) Whereas the Boundary Committee for England(a), acting pursuant to section 15(4) of the Local Government Act 1992(b), has submitted to the Electoral Commission(c) recommendations dated October 2004 on its review of the county of Lancashire: And whereas the Electoral Commission have decided to give effect, with modifications, to those recommendations: And whereas a period of not less than six weeks has expired since the receipt of those recommendations: Now, therefore, the Electoral Commission, in exercise of the powers conferred on them by sections 17(d) and 26(e) of the Local Government Act 1992, and of all other powers enabling them in that behalf, hereby make the following Order: Citation and commencement 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the County of Lancashire (Electoral Changes) Order 2005. (2) This Order shall come into force – (a) for the purpose of proceedings preliminary or relating to any election to be held on the ordinary day of election of councillors in 2005, on the day after that on which it is made; (b) for all other purposes, on the ordinary day of election of councillors in 2005. Interpretation 2. In this Order – (a) The Boundary Committee for England is a committee of the Electoral Commission, established by the Electoral Commission in accordance with section 14 of the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000 (c.41). The Local Government Commission for England (Transfer of Functions) Order 2001 (S.I. -

UNIVERSITY of WINCHESTER the Post-Feeding Larval Dispersal Of

UNIVERSITY OF WINCHESTER The post-feeding larval dispersal of forensically important UK blow flies Molly Mae Mactaggart ORCID Number: 0000-0001-7149-3007 Doctor of Philosophy August 2018 This Thesis has been completed as a requirement for a postgraduate research degree of the University of Winchester. No portion of the work referred to in the Thesis has been submitted in support of an application for another degree or qualification of this or any other university or other institute of learning. I confirm that this Thesis is entirely my own work Copyright © Molly Mae Mactaggart 2018 The post-feeding larval dispersal of forensically important UK blow flies, University of Winchester, PhD Thesis, pp 1-208, ORCID 0000-0001-7149- 3007. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. Copies (by any process) either in full, or of extracts, may be made only in accordance with instructions given by the author. Details may be obtained from the RKE Centre, University of Winchester. This page must form part of any such copies made. Further copies (by any process) of copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the permission (in writing) of the author. No profit may be made from selling, copying or licensing the author’s work without further agreement. 2 Acknowledgements Firstly, I would like to thank my supervisors Dr Martin Hall, Dr Amoret Whitaker and Dr Keith Wilkinson for their continued support and encouragement. Throughout the course of this PhD I have realised more and more how lucky I have been to have had such a great supervisory team. -

Initial Template Document

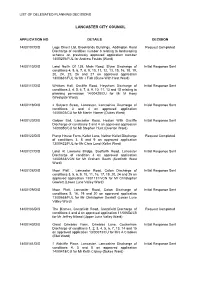

LIST OF DELEGATED PLANNING DECISIONS LANCASTER CITY COUNCIL APPLICATION NO DETAILS DECISION 14/00107/DIS Logs Direct Ltd, Brooklands Buildings, Addington Road Request Completed Discharge of condition number 6 relating to landscaping scheme on previously approved application number 14/00276/FUL for Andrew Foulds (Ward) 14/00110/DIS Land North Of 138, Main Road, Slyne Discharge of Initial Response Sent conditions 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 15, 16, 18, 19, 20, 24, 25, 26 and 27 on approved application 13/00831/FUL for Mr J Fish (Slyne With Hest Ward) 14/00117/DIS Whittam Hall, Oxcliffe Road, Heysham Discharge of Initial Response Sent conditions 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13 and 15 relating to planning permission 14/00428/CU for Mr M Hoey (Westgate Ward) 14/00119/DIS 2 Sulyard Street, Lancaster, Lancashire Discharge of Initial Response Sent conditions 3 and 4 on approved application 14/00403/CU for Mr Martin Horner (Dukes Ward) 14/00120/DIS Golden Ball, Lancaster Road, Heaton With Oxcliffe Initial Response Sent Discharge of conditions 3 and 4 on approved application 14/00050/CU for Mr Stephen Hunt (Overton Ward) 14/00122/DIS Pump House Farm, Kellet Lane, Nether Kellet Discharge Request Completed of conditions 3, 8 and 9 on approved application 13/00422/FUL for Mr Chris Lund (Kellet Ward) 14/00127/DIS Land At Lawsons Bridge, Scotforth Road, Lancaster Initial Response Sent Discharge of condition 4 on approved application 14/00633/VCN for Mr Graham Booth (Scotforth West Ward) 14/00128/DIS Moor Platt , Lancaster Road, Caton Discharge -

3Rd ANNIVERSARY SALE GOOLERATOR L. T.WOOD Co

iOandtralnr Evntittg BATUBDAT, KAY 9 ,19M. HERAlXf COOKING SCHOOL OPENS AT 9 A, M . TOMORROW AVBBAQB DAILT OIBOUtATION THU WKATHBB tor the Month of April, I9S6 Foreeaat of 0 . A Wenthm Banaa. 10 CHICKENS FREE Get Your Tickets Now 5,846 Raitford Forth* Mwtnher o f tha Andlt MoMly ahmdr tanltht and Tnea- t Esoh To Fir* Lnoky Peneas. T» B* Dnwa tetortef, Maj ASPARAGUS Bnrann of OIrcnIatlona. day; wajiner tonight. 9th. MANfiiHfeSTER - A CITY OF VILLAGE CHARM No String* APnched. tm t Send In Thla Oonpon. Eighth Annual Concert VOL. LV., NO. 190. (Cllaailtled AdvettlslBS on Pago ld .| , (SIXTEEN PAGES) POPULAR MARKET MANCHESTER, CONN., MONDAY. MAY 11,1936. PRICE THREE CENTS BnMnoff IMUdlng of th* Louis L. Grant Buckland, Conn. Phone 6370 COOKING SCHOOL OHIO’S PRIMARY As Skyscrapers Blinked Greeting To New Giant of Ocean Airlanes G CLEF CLUB AT STATE OPENS BEING WATCHED MORGENTHAU CALLED Wednesday Evening, May 20 TOMOR^W AT 9 A S T R ^ G U A G E at 8 O'clock IN TAX BILL INQUIRY 3rd ANNIVERSARY SALE Herald’s Aranal Homemak- Borah Grapples M G. 0. P. Treasory’ Head to Be Asked Emanuel Lutheran Church ing Coarse Free to Wom- Organization, CoL Breck Frazier-Letnke Bill to Answer Senator Byrd’s Snbocription— $1.00. en -^ s Ron Each Morning inridge Defies F. D. R. in Is Facing House Test Charge That hroTisions of -Tkrongfa Coming Friday. BaHotmg; Other Primaries Washington, May II.—(AP) ^floor for debate. First on toe sched House Bin Would P em ^ —Over the opposition of ad- ule was a House vote on whether to The Herald'a annual Cooking Washington, May 11.— (A P ) — mlnlBtration leaders, the House discharge the rules committee from ■ehool open* tomorrow morning at Ohio’s primary battleground — to voted 148 to 184 In a standing consideration uf a rule permitting Big Corporations to Evade 9 o’clock in the State theater.