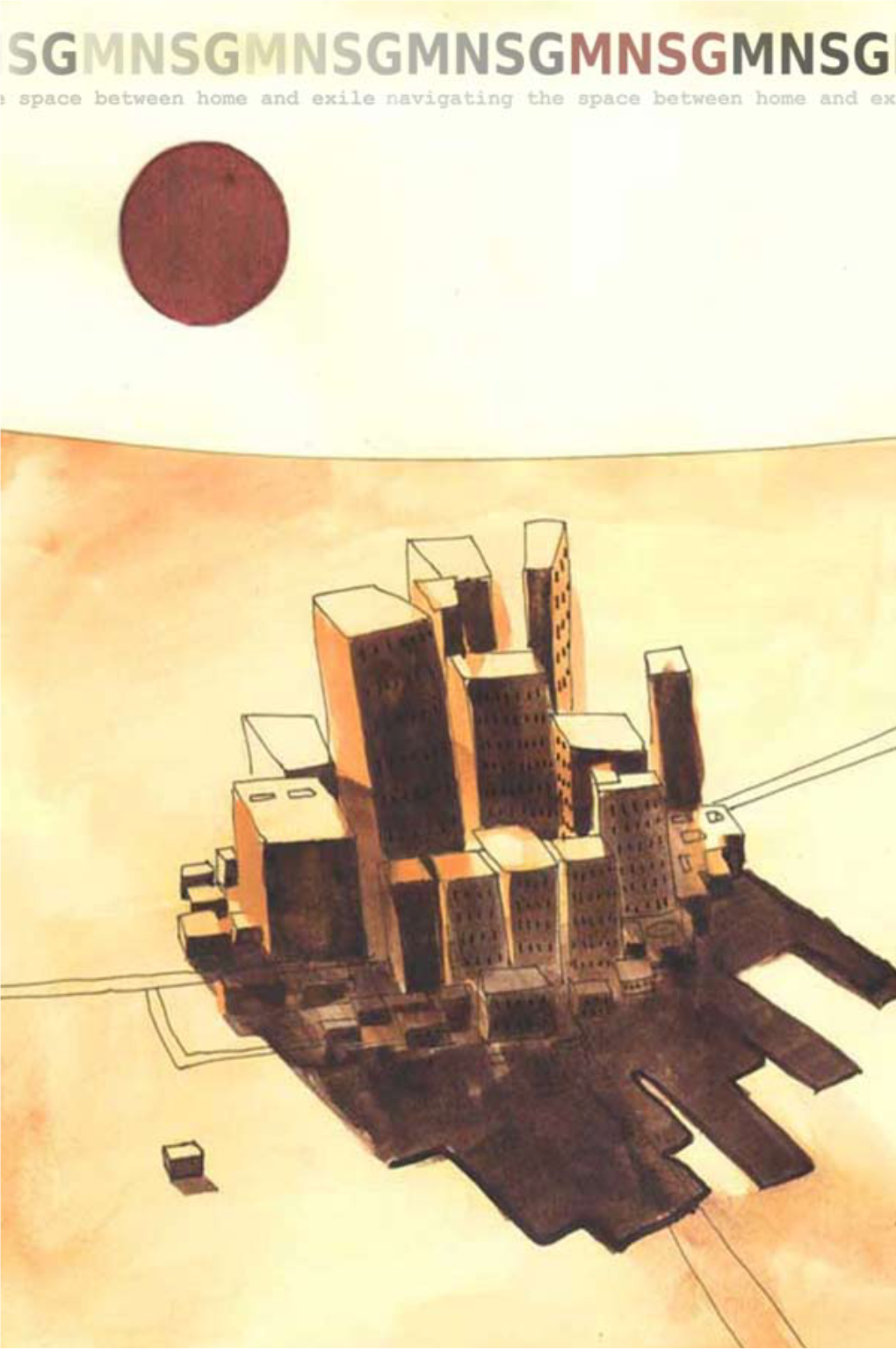

Baghdad Offline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CTC Sentinel Objective

NOVEMBER 2010 . VOL 3 . ISSUE 11-12 COMBATING TERRORISM CENTER AT WEST POINT CTC Sentinel OBJECTIVE . RELEVANT . RIGOROUS Contents AQAP’s Soft Power Strategy FEATURE ARTICLE 1 AQAP’s Soft Power Strategy in Yemen in Yemen By Barak Barfi By Barak Barfi REPORTS 5 Developing Policy Options for the AQAP Threat in Yemen By Gabriel Koehler-Derrick 9 The Role of Non-Violent Islamists in Europe By Lorenzo Vidino 12 The Evolution of Iran’s Special Groups in Iraq By Michael Knights 16 Fragmentation in the North Caucasus Insurgency By Christopher Swift 19 Assessing the Success of Leadership Targeting By Austin Long 21 Revolution Muslim: Downfall or Respite? By Aaron Y. Zelin 24 Recent Highlights in Terrorist Activity 28 CTC Sentinel Staff & Contacts l-qa`ida in the arabian AQAP has avoided many of the domestic Peninsula (AQAP) is currently battles that weakened other al-Qa`ida the most successful of the affiliates by pursuing a shrewd strategy at three al-Qa`ida affiliates home in Yemen.3 The group has sought to Aoperating in the Arab world.1 Unlike its focus its efforts on its primary enemies— sibling partners, AQAP has neither been the Yemeni and Saudi governments, as plagued by internecine conflicts nor has well as the United States—rather than it clashed with its tribal hosts. It has also distracting itself by combating minor launched two major terrorist attacks domestic adversaries that would only About the CTC Sentinel against the U.S. homeland that were only complicate its grand strategy. Some The Combating Terrorism Center is an foiled by a combination of luck and the analysts have argued that this stems independent educational and research help of foreign intelligence agencies.2 from the lessons the group learned from institution based in the Department of Social al-Qa`ida’s failed campaigns in countries Sciences at the United States Military Academy, such as Saudi Arabia and Iraq. -

Terrorist Rehabilitation Terrorist

Terrorism / Political Violence Gunaratna Angell “This is a story of an effort to address the very fundamental challenge in this conflict, deradicalization … both in large mass populations, in small cells, in cliques and ultimately into the individual’s own thought process.” —Maj. Gen. Douglas Stone (retired) (from the Foreword) TERRORIST REHABILITATION Because terrorists are made, not born, it is critically important to world peace that detainees and inmates in uenced by violent ideology are deradicalized and rehabilitated back into society. Exploring the challenges in this formidable endeavor, Terrorist Rehabilitation: The U.S. Experience in Iraq demonstrates through the actual experiences of military personnel, defense contractors, and Iraqi nationals that deradicalization and rehabilitation programs can succeed and have the capability to positively impact thousands of would-be terrorists globally if utilized to their full capacity. Custodial and community rehabilitation of terrorists and extremists is a new frontier in the ght against terrorism. This forward-thinking volume: • Highlights the success of a rehabilitation program curriculum in Iraq • Encourages individuals and governments to embrace rehabilitation as the next most logical step in ghting terrorism • Examines the recent history of threat groups in Iraq • Demonstrates where the U.S. went awry in its war effort, and the steps it took to correct the situation • Describes religious, vocational training, education, creative expression, and Tanweer programs introduced to the detainee population • Provides insight into future steps based on lessons learned from current rehabilitation programs It is essential that we shift the focus from solely detainment and imprisonment to addressing the ideological mindset during prolonged incarceration. It is possible to effect an ideological transformation in detainees that qualies them to be reclassied as no longer posing a security threat. -

Iranian Strategy in Syria

*SBOJBO4USBUFHZJO4ZSJB #:8JMM'VMUPO KPTFQIIPMMJEBZ 4BN8ZFS BKPJOUSFQPSUCZ"&*ŦT$SJUJDBM5ISFBUT1SPKFDUJ/45*565&'035)&456%:0'8"3 .BZ All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. ©2013 by Institute for the Study of War and AEI’s Critical Threats Project Cover Image: Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad, and Hezbollah’s Sheikh Hassan Nasrallah appear together on a poster in Damascus, Syria. Credit: Inter Press Service News Agency Iranian strategy in syria Will Fulton, Joseph Holliday, & Sam wyer May 2013 A joint Report by AEI’s critical threats project & Institute for the Study of War ABOUT US About the Authors Will Fulton is an Analyst and the IRGC Project Team Lead at the Critical Threats Project at the American Enterprise Institute. Joseph Holliday is a Fellow at the Institute for the Study of War. Sam Wyer served as an Iraq Analyst at ISW from September 2012 until February 2013. The authors would like to thank Kim and Fred Kagan, Jessica Lewis, and Aaron Reese for their useful insights throughout the writing and editorial process, and Maggie Rackl for her expert work on formatting and producing this report. We would also like to thank our technology partners Praescient Analytics and Palantir Technologies for providing us with the means and support to do much of the research and analysis used in our work. About the Institute for the Study of War The Institute for the Study of War (ISW) is a non-partisan, non-profit, public policy research organization. ISW advances an informed understanding of military affairs through reliable research, trusted analysis, and innovative education. -

The American University in Cairo Press

TheThe AmericanAmerican 2009 UniversityUniversity inin Cairo Cairo PressPress Complete Catalog Fall The American University in Cairo Press, recognized “The American University in Cairo Press is the Arab as the leading English-language publisher in the region, world’s top foreign-language publishing house. It has currently offers a backlist of more than 1000 publica- transformed itself into one of the leading players in tions and publishes annually up to 100 wide-ranging the dialog between East and West, and has produced academic texts and general interest books on ancient a canon of Arabic literature in translation unmatched and modern Egypt and the Middle East, as well as in depth and quality by any publishing house in the Arabic literature in translation, most notably the works world.” of Egypt’s Nobel laureate Naguib Mahfouz. —Egypt Today New Publications 9 Marfleet/El Mahdi Egypt: Moment of Change 22 Abdel-Hakim/Manley Traveling through the 10 Masud et al. Islam and Modernity Deserts of Egypt 14 McNamara The Hashemites 28 Abu Golayyel A Dog with No Tail 23 Mehdawy/Hussein The Pharaoh’s Kitchen 31 Alaidy Being Abbas el Abd 15 Moginet Writing Arabic 2 Arnold The Monuments of Egypt 30 Mustafa Contemporary Iraqi Fiction 31 Aslan The Heron 8 Naguib Women, Water, and Memory 29 Bader Papa Sartre 20 O’Kane The Illustrated Guide to the Museum 9 Bayat Life as Politics of Islamic Art 13 al-Berry Life is More Beautiful than Paradise 2 Ratnagar The Timeline History of Ancient Egypt 15 Bloom/Blair Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art 33 Roberts, R.A. -

The Coming Turkish- Iranian Competition in Iraq

UNITeD StateS INSTITUTe of Peace www.usip.org SPeCIAL RePoRT 2301 Constitution Ave., NW • Washington, DC 20037 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPO R T Sean Kane This report reviews the growing competition between Turkey and Iran for influence in Iraq as the U.S. troop withdrawal proceeds. In doing so, it finds an alignment of interests between Baghdad, Ankara, and Washington, D.C., in a strong and stable Iraq fueled by increased hydrocarbon production. Where possible, the United States should therefore encourage The Coming Turkish- Turkish and Iraqi cooperation and economic integration as a key part of its post-2011 strategy for Iraq and the region. This analysis is based on the author’s experiences in Iraq and Iranian Competition reviews of Turkish and Iranian press and foreign policy writing. ABOUT THE AUTHO R in Iraq Sean Kane is the senior program officer for Iraq at the United States Institute of Peace (USIP). He assists in managing the Institute’s Iraq program and field mission in Iraq and serves as the Institute’s primary expert on Iraq and U.S. policy in Iraq. Summary He previously worked for the United Nations Assistance Mission • The two rising powers in the Middle East—Turkey and Iran—are neighbors to Iraq, its for Iraq from 2006 to 2009. He has published on the subjects leading trading partners, and rapidly becoming the most influential external actors inside of Iraqi politics and natural resource negotiations. The author the country as the U.S. troop withdrawal proceeds. would like to thank all of those who commented on and provided feedback on the manuscript and is especially grateful • Although there is concern in Washington about bilateral cooperation between Turkey and to Elliot Hen-Tov for generously sharing his expertise on the Iran, their differing visions for the broader Middle East region are particularly evident in topics addressed in the report. -

News Harvard University

THE CENTER FOR MIDDLE EASTERN STUDIES, NEWS HARVARD UNIVERSITY SPRING 2015 1 LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR A message from William Granara 2 SHIFTING TOWARDS THE ARABIAN PENINSULA Announcing a new lecture series 3 NEWS AND NOTES Updates from faculty, students and visiting researchers 12 EVENT HIGHLIGHTS Spring lectures, workshops, and conferences LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR SPRING 2015 HIGHLIGHTS I’M HAPPY TO REPORT THAT WE ARE DRAWING TO THE CLOSE OF AN ACADEMIC YEAR FULL OF ACTIVITY. CMES was honored to host a considerable number of outstanding lectures this year by eminent scholars from throughout the U.S. as well as from the Middle East and Europe. I mention only a few highlights below. Our new Middle Eastern Literatures initiative was advanced by several events: campus visits by Arab novelists Mai Nakib (Kuwait), Ahmed Khaled Towfik (Egypt), and Ali Bader (Iraq); academic lectures by a range of literary scholars including Hannan Hever (Yale) on Zionist literature and Sheida Dayani (NYU) on contemporary Persian theater; and a highly successful seminar on intersections between Arabic and Turkish literatures held at Bilgi University in Istanbul, which included our own Professor Cemal Kafadar, several of our graduate students, and myself. In early April, CMES along with two Harvard Iranian student groups hosted the first Harvard Iranian Gala, which featured a lecture by Professor Abbas Milani of Stanford University and was attended by over one hundred guests from the broader Boston Iranian community. Also in April, CMES co-sponsored an international multilingual conference on The Thousand and One Nights with INALCO, Paris. Our new Arabian Peninsula Studies Lecture Series was inaugurated with a lecture by Professor David Commins of Dickinson College, and we are happy to report that this series will continue in both the fall and spring semesters of next year thanks to the generous support of CMES alumni. -

Mcallister Bradley J 201105 P

REVOLUTIONARY NETWORKS? AN ANALYSIS OF ORGANIZATIONAL DESIGN IN TERRORIST GROUPS by Bradley J. McAllister (Under the Direction of Sherry Lowrance) ABSTRACT This dissertation is simultaneously an exercise in theory testing and theory generation. Firstly, it is an empirical test of the means-oriented netwar theory, which asserts that distributed networks represent superior organizational designs for violent activists than do classic hierarchies. Secondly, this piece uses the ends-oriented theory of revolutionary terror to generate an alternative means-oriented theory of terrorist organization, which emphasizes the need of terrorist groups to centralize their operations. By focusing on the ends of terrorism, this study is able to generate a series of metrics of organizational performance against which the competing theories of organizational design can be measured. The findings show that terrorist groups that decentralize their operations continually lose ground, not only to government counter-terror and counter-insurgent campaigns, but also to rival organizations that are better able to take advantage of their respective operational environments. However, evidence also suggests that groups facing decline due to decentralization can offset their inability to perform complex tasks by emphasizing the material benefits of radical activism. INDEX WORDS: Terrorism, Organized Crime, Counter-Terrorism, Counter-Insurgency, Networks, Netwar, Revolution, al-Qaeda in Iraq, Mahdi Army, Abu Sayyaf, Iraq, Philippines REVOLUTIONARY NETWORK0S? AN ANALYSIS OF ORGANIZATIONAL DESIGN IN TERRORIST GROUPS by BRADLEY J MCALLISTER B.A., Southwestern University, 1999 M.A., The University of Leeds, United Kingdom, 2003 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSPHY ATHENS, GA 2011 2011 Bradley J. -

RRTA 836 (12 September 2012)

1201934 [2012] RRTA 836 (12 September 2012) DECISION RECORD RRT CASE NUMBER: 1201934 DIAC REFERENCE(S): CLF2011/135787 COUNTRY OF REFERENCE: Iraq TRIBUNAL MEMBER: Vanessa Moss DATE: 12 September 2012 PLACE OF DECISION: Perth DECISION: The Tribunal remits the matter for reconsideration with the direction that the applicant satisfies s.36(2)(a) of the Migration Act. STATEMENT OF DECISION AND REASONS APPLICATION FOR REVIEW 1. This is an application for review of a decision made by a delegate of the Minister for Immigration to refuse to grant the applicant a Protection (Class XA) visa under s.65 of the Migration Act 1958 (the Act). 2. The applicant who claims to be a citizen of Iraq, applied to the Department of Immigration for the visa on [date deleted under s.431(2) of the Migration Act 1958 as this information may identify the applicant] August 2011. 3. The delegate refused to grant the visa [in] January 2012, and the applicant applied to the Tribunal for review of that decision. RELEVANT LAW 4. Under s.65(1) a visa may be granted only if the decision maker is satisfied that the prescribed criteria for the visa have been satisfied. The criteria for a protection visa are set out in s.36 of the Act and Part 866 of Schedule 2 to the Migration Regulations 1994 (the Regulations). An applicant for the visa must meet one of the alternative criteria in s.36(2)(a), (aa), (b), or (c). That is, the applicant is either a person in respect of whom Australia has protection obligations under the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees as amended by the 1967 Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees (together, the Refugees Convention, or the Convention), or on other ‘complementary protection’ grounds, or is a member of the same family unit as a person in respect of whom Australia has protection obligations under s.36(2) and that person holds a protection visa. -

On Dictatorship, Literature and the Coming Revolution: Regime and Novels in Iraq 1995-2003

NIDABA AN INTERDISCIPLINARY JOURNAL OF MIDDLE EAST STUDIES CENTER FOR MIDDLE EASTERN STUDIES | LUND UNIVERSITY On Dictatorship, Literature and the Coming Revolution: Regime and Novels in Iraq 1995-2003 Ronen Zeidel UNIVERSITY OF HAIFA [email protected] The last years of the Saddam regime in Iraq are often described as the disintegration of the very pow- erful state as the result of the cumulative impact of wars and sanctions. Yet in one field, literature, the Saddam regime maintained a firmer grip during its last years. This article describes the regime’s politics with regard to literature and literary production, concentrating on the novel, in the period between 1995–2003. The article explains why the regime targeted the literary field before its doom and why it focused on the novel. Examining the Iraqi regime and its “eccentricity” during this period illuminates the control of the totalitarian Ba’ath dictatorship, and sheds a new light on the belated emergence of literary reaction, silently hatching during that period, in the form of a new literary generation that would revolutionize Iraqi cultural life after 2003. This revolution is often calledDeba‘athification and only its political and bureaucratic aspects are given attention. This article is, thus, about the cultural background of deba‘athification. Keywords: Iraq; literature; totalitarianism; cultural revolution ON DICTATORSHIP, LITERATURE AND THE COMING REVOLUTION: REGIME AND NOVELS IN IRAQ 1995-2003 63 INTRODUCTION Caiani and Catherine Cobham’s (2013), The Iraqi Novel: Key Writers, Key Texts. This book is not fo- The last years of the Saddam Hussein’s regime cused on the 1990s and is more interested in the style in Iraq are often described as the disintegration of and literary value of key texts than in the context a very strong and monolithic state as the result of of their publication or the discourse they produce. -

1 the Human Cost of US Interventions in Iraq

The Human Cost of U.S. Interventions in Iraq: A History From the 1960s Through the Post-9/11 Wars Zainab Saleh1 October 13, 2020 The United States government has justified decades of intervention in Iraq in a variety of ways, the most recent of which is the current “war on terrorism.” All of these interventions have had devastating costs and consequences for Iraqis. Since the 1960s, the U.S. has treated Iraq as essential to its own economic and geopolitical interests; Iraqi arms purchases have bolstered the American military-industrial complex and stable access to Middle East oil has secured U.S. dominance in the global economy. As the U.S. has pursued these interests in Iraq, U.S. interventions have reshaped the Iraqi social, political, and cultural landscape. While the role the United States has played in Iraq since the 1960s is beginning to receive some scholarly attention, it remains widely unknown to the American public. Iraqis have lived in the shadow of U.S. interventions for decades, whereby the United States has attempted to control events and resources in the Gulf region. In 1958, the fall of the Iraqi monarchy brought an end to British influence in Iraq and the emergence of the United States as a major player in Iraqi affairs. In 1963, under the pretext of protecting the region from a communist threat, the Central Intelligence Agency backed the Ba‘th coup, an Arab nationalist party, after Iraq nationalized most of its oil fields. During the 1980s, the United States supported Saddam Hussein’s regime and prolonged the Iran-Iraq War in order to safeguard its national interests in the region, which entailed weakening Iran after the Islamic Revolution in 1979 to prevent it from posing a threat to U.S. -

Memory, Trauma, and Citizenship: Arab Iraqi Women

MEMORY, TRAUMA, AND CITIZENSHIP: ARAB IRAQI WOMEN by Sajedeh Zahraei A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Social Work University of Toronto © Copyright by Sajedeh Zahraei 2014 Memory, Trauma, and Citizenship: Arab Iraqi Women Sajedeh Zahraei Doctor of Philosophy Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work University of Toronto 2014 Abstract This dissertation examines Arab Iraqi refugee women’s experiences of the “war on terror” from a gendered historical perspective within the contemporary structural violence of state policies and practices in the Canadian context. Drawing on critical anti-racist and anti- colonial feminist theoretical frameworks, I argue that Iraqi refugee women experience the “war on terror” as both a historical and contemporary phenomenon. Historical ideological constructions of Arab Muslim women as terrorists, unsuitable for integration into Canadian society, facilitate their current social exclusion and eviction from civil society. Examining the trauma of the “war on terror” and Iraqi women’s everyday experiences in this light shifts the focus away from disease focused psychiatric conceptualizations of trauma while centering the participants’ experiences and varied responses to their circumstances in the Canadian context. Using a historically-based multi-level trauma framework of the “war on terror” enables us to move away from artificial binaries of “us” and “them” and facilitate a better understanding of the structural dynamics of our interconnected world in order to foster alliances across transnational borders and boundaries aimed at developing multi-level transformative interventions. ii Dedication This work is dedicated to the memory of my beloved mother, Saleemeh Salman Mohammed Al- Imrani (1926-2008), who continues to be a source of love and inspiration long after she is gone. -

Latin America, Al-Andalus and the Arab World

LATIN AMERICA, AL-ANDALUS AND THE ARAB WORLD An International Conference at the American University of Beirut April 15, 17 and 18, 2018 Sponsored by the Prince Alwaleed bin Talal bin Abdelaziz Alsaud Center for American Studies and Research (CASAR) With the Ph.D. Program in Theatre and Performance at the CUNY Graduate Center and the Martin E. Segal Theatre Center, which are part of CUNY’s Memorandum of Understanding with AUB and AUB’s Theater Initiative Organized by Robert Myers, Professor of English and Director, Theater Initiative With the Assistance of Amy Zenger, Director, Center for American Studies Additional support provided by the Center for Arts and Humanities (CAH) and the Mellon Foundation, the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, the Department of English, the Department of Arabic and the Department of Fine Arts and Art History, and Notre Dame University—Louaize, Lebanon. Sunday, April 15 – Hammana, Lebanon Blood Wedding, by Federico García Lorca, directed and translated by Sahar Assaf, Co-Director of AUB’s Theater Initiative and Assistant Professor of Theater, AUB. Produced by Robert Myers and the Theater Initiative at AUB. (Transportation will be provided for conference participants) Tuesday, April 17 – College Hall, Auditorium B1, AUB Coffee – 8:30 am Welcome – 9:00 am Nadia al Cheikh, Dean of FAS, American University of Beirut Intro to Conference and Keynote Speaker by Robert Myers (AUB) Keynote “The Secret Literature of the Last Muslims of Spain” Luce López-Baralt (University of Puerto Rico) Coffee Break – 10:30 am Panel 1 –