Iraq's Universities and Female Students in the Midst Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reaching Beyond the Ivory Tower: a “How To” Manual *

Reaching Beyond the Ivory Tower: A “How To” Manual * Daniel Byman and Matthew Kroenig Security Studies (forthcoming, June 2016) *For helpful comments on earlier versios of this article, the authors would like to thank Michael C. Desch, Rebecca Friedman, Bruce Jentleson, Morgan Kaplan, Marc Lynch, Jeremy Shapiro, and participants in the Program on International Politics, Economics, and Security Speaker Series at the University of Chicago, participants in the Nuclear Studies Research Initiative Launch Conference, Austin, Texas, October 17-19, 2013, and members of a Midwest Political Science Association panel. Particular thanks to two anonymous reviewers and the editors of Security Studies for their helpful comments. 1 Joseph Nye, one of the rare top scholars with experience as a senior policymaker, lamented “the walls surrounding the ivory tower never seemed so high” – a view shared outside the academy and by many academics working on national security.1 Moreover, this problem may only be getting worse: a 2011 survey found that 85 percent of scholars believe the divide between scholars’ and policymakers’ worlds is growing. 2 Explanations range from the busyness of policymakers’ schedules, a disciplinary shift that emphasizes theory and methodology over policy relevance, and generally impenetrable academic prose. These and other explanations have merit, but such recommendations fail to recognize another fundamental issue: even those academic works that avoid these pitfalls rarely shape policy.3 Of course, much academic research is not designed to influence policy in the first place. The primary purpose of academic research is not, nor should it be, to shape policy, but to expand the frontiers of human knowledge. -

Freedom Or Theocracy?: Constitutionalism in Afghanistan and Iraq Hannibal Travis

Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights Volume 3 | Issue 1 Article 4 Spring 2005 Freedom or Theocracy?: Constitutionalism in Afghanistan and Iraq Hannibal Travis Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njihr Recommended Citation Hannibal Travis, Freedom or Theocracy?: Constitutionalism in Afghanistan and Iraq, 3 Nw. J. Int'l Hum. Rts. 1 (2005). http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njihr/vol3/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Copyright 2005 Northwestern University School of Law Volume 3 (Spring 2005) Northwestern University Journal of International Human Rights FREEDOM OR THEOCRACY?: CONSTITUTIONALISM IN AFGHANISTAN AND IRAQ By Hannibal Travis* “Afghans are victims of the games superpowers once played: their war was once our war, and collectively we bear responsibility.”1 “In the approved version of the [Afghan] constitution, Article 3 was amended to read, ‘In Afghanistan, no law can be contrary to the beliefs and provisions of the sacred religion of Islam.’ … This very significant clause basically gives the official and nonofficial religious leaders in Afghanistan sway over every action that they might deem contrary to their beliefs, which by extension and within the Afghan cultural context, could be regarded as -

Mattia Gallotti John Michael Editors

Studies in the Philosophy of Sociality 4 Mattia Gallotti John Michael Editors Perspectives on Social Ontology and Social Cognition Perspectives on Social Ontology and Social Cognition Studies in the Philosophy of Sociality Volume 4 Editor-in-Chief Raimo Tuomela (Prof. Emer., University of Helsinki, University of Munich) Managing Editors Hans Bernhard Schmid (Prof., University of Basel) Jennifer Hudin (Lecturer, University of California, USA) Advisory Board Robert Audi, Notre Dame University (Philosophy) Michael Bratman, Stanford University (Philosophy) Cristiano Castelfranchi, University of Siena (Cognitive Science) David Copp, University of California at Davis (Philosophy) Ann Cudd, University of Kentucky (Philosophy) John Davis, Marquette University and University of Amsterdam (Economics) Wolfgang Detel, University of Frankfurt (Philosophy) Andreas Herzig, University of Toulouse (Computer Science) Ingvar Johansson, Umeå University (Philosophy) Byron Kaldis, University of Athens (Philosophy) Martin Kusch, University of Vienna (Philosophy) Christopher Kutz, University of California at Berkeley (Law) Eerik Lagerspetz, University of Turku (Philosophy) Pierre Livet, Universite de Provence Tony Lawson, University of Cambridge (Economics) Kirk Ludwig, University of Florida (Philosophy) Uskali Mäki, Academy of Finland (Philosophy) Kay Mathiesen, University of Arizona (Information Science and Philosophy) Larry May, Vanderbilt University (Philosophy and Law) Georg Meggle, University of Leipzig (Philosophy) Anthonie Meijers, University of Eindhoven -

Basrah, Urban Planning and Regeneration Program

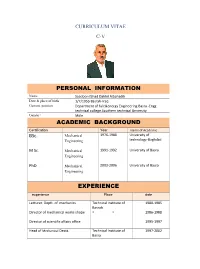

CURRICULUM VITAE C-V PERSONAL INFORMATION Name Saadoon fahad Dakhil Albahadili Date & place of birth 1/7/1955 Basrah-Iraq Current position Department of fule&energy Engineering.Basra -Engg technical college.Southern technical Unversity Male ا Gender ACADEMIC BACKGROUND Certification Year Name of Academic BSc. Mechanical 1976-1980 University of Engineering technology-Baghdad M Sc. Mechanical 1991-1992 University of Basra Engineering PhD Mechanical 2003-2006 University of Basra Engineering EXPERIENCE experience Place date Lecturer, Deptt. of mechanics Technical Institute of 1980-1985 Basrah Director of mechanical works shope = = 1986-1988 Director of scientific affairs office 1995-1997 Head of Mechanical Deptt. Technical Institute of 1997-2002 Basra Head of fuel &energy Engineering Technical College/ 2008-2011 Basra Scientific titles Title period date Assit lecture 1982-1990 23/6/2198 20/1/1990 Lecturer 1990-1997 1997-2015 3/9/1997 Assist Prof Professor 2015 15/6/2015 PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT • Internal combustion engines\fuel • Internal combustion engines \noise redaction • Heat transfer ; theoretical analysis . • Numerical solution for mechanical ( Fluid & thermal ) problems. • Simulation solution for internal combustion engine( Combustion & fuel spray. ) • FLUENT software ,representation. • High experience into engine design and maintanace. High graduate supervisor& Scientice activeties Fourty students Msc degree. Six student phD degree. External examiner to the Andahar University- INDIA Reviwer to the Thmasal University –Bankok –Tiland . Rviwer to the Northwest Agriculture and Forestry University, Yangling 712100, China. Performing many mechanical tests for public and indigenous corporations. Offering engineering consultations in mechanical designs for public and indigenous corporations. Consultative status with the Federation of Industries –BASRAH. Implementation of projects in the oil industry. -

Theoretical Models of Consciousness: a Scoping Review

brain sciences Review Theoretical Models of Consciousness: A Scoping Review Davide Sattin 1,2,*, Francesca Giulia Magnani 1, Laura Bartesaghi 1, Milena Caputo 1, Andrea Veronica Fittipaldo 3, Martina Cacciatore 1, Mario Picozzi 4 and Matilde Leonardi 1 1 Neurology, Public Health, Disability Unit—Scientific Department, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico Carlo Besta, 20133 Milan, Italy; [email protected] (F.G.M.); [email protected] (L.B.); [email protected] (M.C.); [email protected] (M.C.); [email protected] (M.L.) 2 Experimental Medicine and Medical Humanities-PhD Program, Biotechnology and Life Sciences Department and Center for Clinical Ethics, Insubria University, 21100 Varese, Italy 3 Oncology Department, Mario Negri Institute for Pharmacological Research IRCCS, 20156 Milan, Italy; veronicaandrea.fi[email protected] 4 Center for Clinical Ethics, Biotechnology and Life Sciences Department, Insubria University, 21100 Varese, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-02-2394-2709 Abstract: The amount of knowledge on human consciousness has created a multitude of viewpoints and it is difficult to compare and synthesize all the recent scientific perspectives. Indeed, there are many definitions of consciousness and multiple approaches to study the neural correlates of consciousness (NCC). Therefore, the main aim of this article is to collect data on the various theories of consciousness published between 2007–2017 and to synthesize them to provide a general overview of this topic. To describe each theory, we developed a thematic grid called the dimensional model, which qualitatively and quantitatively analyzes how each article, related to one specific theory, debates/analyzes a specific issue. -

A Theory of Normative Thinking

Sharing our normative worlds: A theory of normative thinking A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Australian National University by Ivan Gonzalez-Cabrera in August 2017 © Copyright by Ivan Gonzalez-Cabrera 2017 All Rights Reserved Statement of Originality This thesis is solely the work of its author. No part of it has previously been submitted for any degree or is currently being submitted for any other degree. To the best of my knowledge, any help received in preparing this thesis, and all sources used, have been duly acknowledged. Parts of this thesis draw on earlier published work. Chapter 3 is taken, with some changes, from Gonzalez-Cabrera (forthcoming): On social tolerance and the evolution of human normative guidance. Sections 4.4 and 4.5 of this chapter are based on worked published in Tomasello and Gonzalez-Cabrera (2017): The role of ontogeny in the evolution of human cooperation. These sections have been modified to meet university guidelines. Signed, Ivan Gonzalez-Cabrera i To my partner and friend, Ana. ii Acknowledgments This thesis represents the end of a long journey. The conception of the project started when I was a graduate student at the University of Tokyo. I am especially grateful to Tomoko Ishida, Ryota Morimoto, Senji Tanaka, Sohei Yajima, and all the members of the interdisciplinary group on evolutionary ethics and human ecology for their support during those early days. Thanks also to Yosaku Nishiwaki and Yoshiyuki Hirono for his encouragement to pursue a Ph.D. in philosophy. That project crystallized only years later as a graduate student at the Australian National University (ANU). -

The Coming Turkish- Iranian Competition in Iraq

UNITeD StateS INSTITUTe of Peace www.usip.org SPeCIAL RePoRT 2301 Constitution Ave., NW • Washington, DC 20037 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPO R T Sean Kane This report reviews the growing competition between Turkey and Iran for influence in Iraq as the U.S. troop withdrawal proceeds. In doing so, it finds an alignment of interests between Baghdad, Ankara, and Washington, D.C., in a strong and stable Iraq fueled by increased hydrocarbon production. Where possible, the United States should therefore encourage The Coming Turkish- Turkish and Iraqi cooperation and economic integration as a key part of its post-2011 strategy for Iraq and the region. This analysis is based on the author’s experiences in Iraq and Iranian Competition reviews of Turkish and Iranian press and foreign policy writing. ABOUT THE AUTHO R in Iraq Sean Kane is the senior program officer for Iraq at the United States Institute of Peace (USIP). He assists in managing the Institute’s Iraq program and field mission in Iraq and serves as the Institute’s primary expert on Iraq and U.S. policy in Iraq. Summary He previously worked for the United Nations Assistance Mission • The two rising powers in the Middle East—Turkey and Iran—are neighbors to Iraq, its for Iraq from 2006 to 2009. He has published on the subjects leading trading partners, and rapidly becoming the most influential external actors inside of Iraqi politics and natural resource negotiations. The author the country as the U.S. troop withdrawal proceeds. would like to thank all of those who commented on and provided feedback on the manuscript and is especially grateful • Although there is concern in Washington about bilateral cooperation between Turkey and to Elliot Hen-Tov for generously sharing his expertise on the Iran, their differing visions for the broader Middle East region are particularly evident in topics addressed in the report. -

Ibn Al-Haitham)

University of Baghdad College of Education for Pure Science (Ibn Al-Haitham) This paper is Blank Ibn Al-Haitham 1St. International Scientific Conference – 2017 (IHSCICONF) Proceedings IOP Publisher Volume Preface IHSCICONF 2017, International Conference on Biology, Chemistry, Computer Science, Mathematics, and Physics, Take place in Baghdad, Iraq, from December 13-14, 2017. IHSCICONF 2017 is assisted by the College of education for pure science – Ibn Al Haitham \ University of Baghdad and with supporting of the American Chemical Society (ACS) in Iraq. IHSCICONF 2017 aimed to distills the most current knowledge on a rapidly advancing discipline in one conference. Join key researchers and established professionals in the field of Biology, Chemistry, Computer Science, Mathematics and Physics as they assess the current state-of-the-art and roadmap crucial areas for future research. We aimed to build an idea-trading platform for the purpose of encouraging researcher participating in this event. The papers to be presented at IHSCICONF 2017 address many grand challenges in sciences. The full papers that presented are peer- reviewed by three expert reviewers. This paper is Blank Ibn Al-Haitham 1St. International Scientific Conference – 2017 (IHSCICONF) Proceedings IOP Publisher Volume Prof. Dr. Sameer Atta Makki ([email protected]) Editor in Chief Assist.Prof. Dr. Firas Abdul ([email protected]) Manager and Hameed Abdul Latef Editor Prof. Dr. Luma Naji Mohammed (dr. [email protected]) Editor Tawfiq Prof. Dr.Nahla Abud AL-Radi ([email protected]) Editor AL- Bakri Inst. Dr. Raied Mustafa Shakir ([email protected]) Editor This paper is Blank Ibn Al-Haitham 1St. International Scientific Conference – 2017 (IHSCICONF) Proceedings IOP Publisher Volume the Conference Opening ceremony of ceremony Opening Ibn Al-Haitham 1St. -

Paul Doty 1920–2011

Spring 2012 www.belfercenter.org Paul Doty 1920 –2011 Paul Doty , who founded the Belfer Center in 1973, died on December 5, 2011. He was 91. Steven E. Miller , a member of Paul Doty’s early staff who is now director of the Belfer Center’s International Security Program and editor-in-chief of the journal International Security , remembers his colleague and friend in comments below. Miller’s complete remembrance, along with other tributes, can be found at http://rememberingpauldoty.org/ . S aul Doty was a man of immense accom - N O M plishment: a world class figure in both M I P S Z science and public policy, a builder of institu - T I F tions, an intellectual leader, a stalwart at Har - M O vard for more than 60 years. He had major T accomplishments in biochemistry and molec - ular biology. He was a leading expert on nuclear arms control. He founded Harvard’s Biochemistry Department and the Kennedy School’s Belfer Center for Science and Inter - national Affairs. He created leading journals in both fields. He built teams of colleagues that were second to none. His former students and fellows represent a legacy that would make any scholar proud. Despite his stature, he was unassuming, Paul Doty (left) asks a question of Senator Sam Nunn (center right) during a JFK Jr. Forum in 2010 titled “Nuclear almost self-effacing, and approachable. He Tipping Point.” Panelists included Belfer Center Director Graham Allison (right) and David Sanger , senior fellow. rose high, but on his merits, because he seemed to lack almost completely the self- underestimate, he was exceptionally effective and was unflagging in his efforts to make a promotional instinct. -

Aston University IRAQ (This Update: 23Rd March 2011)

Aston University IRAQ (This update: 23rd March 2011) Admissions to Masters at Aston Iraqi Bachelors degree: Takes 4 years to complete. Courses in medicine take 6 years, while courses in pharmacy, architecture, dentistry and veterinary medicine take 5 years to complete. International Office advise for PG admissions: • 70% to be equivalent to a 2.1 • 65% equivalent to a 2.2 For students holding Bachelor’s degrees from the below institutions: • Al-Nahrain Uni , Baghdad • Al-Mustansiriyah University • The University of Basrah • University of Baghdad • Duhok University • Koya University • University of Mosul • The University of Salahaddin (Arbil) • Hawler Medical University (Arbil) • Sulaimani University • The University of Technology (Baghdad) International Office recommends for students from Universities not listed above but listed on Naric they can also be considered for Masters at Aston, but with more caution than the above. Admissions to PhD at Aston Iraqi Masters degree: A Masters is appropriate for admissions to PhD. Would advise also checking for a Bachelors at 70% and above. Masters degrees vary from two to three years in duration and are offered in most fields including arts, exact and natural sciences, engineering and technology, medicine, dentistry, and agriculture. For admission onto local Master’s programmes, the majority of universities require candidates to obtain an overall score of at least 65% in the Bachelor degree. Most Master’s courses consist of three semesters culminating in end of term examinations. Successful students proceed to undertake one years’ research work in his or her field of study. This period may be extended by up to six months. -

Equality Now 1994-1995 Report Equality Now

EQUALITY NOW 1994-1995 REPORT EQUALITY NOW Equality Now international force, capable outside the scope of the was founded in of rapid response to crisis mainstream human rights 1992 to work situations and committed to movement, such as domestic for the protec- voicing a worldwide call for violence, reproductive rights, tion and pro- justice and equality for trafficking of women, female motion of the human rights women. Equality Now genital mutilation, and equal of women around the world. addresses issues which have access to economic opportu- Working with national historically been considered nity and political participation. human rights groups and individual activists, Equality SOMMAIRE Now documents human Egalité Maintenant a été fondée en 1992 afin de travailler pour la protection et la pro- motion des droits individuels des femmes dans le monde entier. Travaillant avec des rights violations against groupes locaux de droits individuels et des militants individuels, Egalité Maintenant women and adds an inter- documente les violations de ces droits et ajoute un aspect international d’action pour soutenir les efforts locaux et nationaux au nom des droits des femmes et au nom des national action component— femmes individuelles qui subissent des violations de leurs droits humains. Egalité Maintenant aborde les questions qui ont généralement été considérées en dehors du to support their efforts to champ des droits humains internationaux, telles que la traîte des femmes, la violence advance women’s rights and familiale, les droits de reproduction, la mutilation féminine génitale et égalité d’accès économiques et participation politique. to defend individual women RESUMEN who are suffering abuse. -

The University at War1

The University at War1 By Hugh Gusterson (George Mason University) The political scientist Mark Duffield has observed that the effect of Western intervention in Iraq has actually been to “demodernize” that country.2 This is ironic given that the military campaigns against Iraq and Afghanistan have been accompanied by narratives of the West’s obligation to modernize backward nations. Nowhere is the truth of Duffield’s observation clearer than in the story of what has happened to Iraq’s education system, especially its higher education system. Western intervention has ended up destroying Iraq’s universities, formerly among the best in the region, as functional institutions. “Up to the Early 1980s, Iraq’s educational system was considered one of the best in the Middle East. As a result of its drastic and prolonged decline since then, it is now one of the weakest,” concludes a 2008 official report.3 Iraq has a long and venerable tradition as a center of higher learning. As Eric Herring observes, “Iraqis tend to see themselves proudly as coming from a society that was the cradle of civilization in its ancient contributions to the development of writing, legal systems, libraries, mathematics, astronomy, medicine, technology and so on.”4 Mosul houses the world’s oldest known library, which dates to the seventh century. And In 832 the construction of the Byat al Hikma (house of Wisdom) established the new capital [Baghdad] as an unrivaled center of scholarship and intellectual exchange. The tradition of research there brought advances in astronomy, optics, physics and mathematics. The father of algebra, Al Khawarizmii, labored among its scrolls.