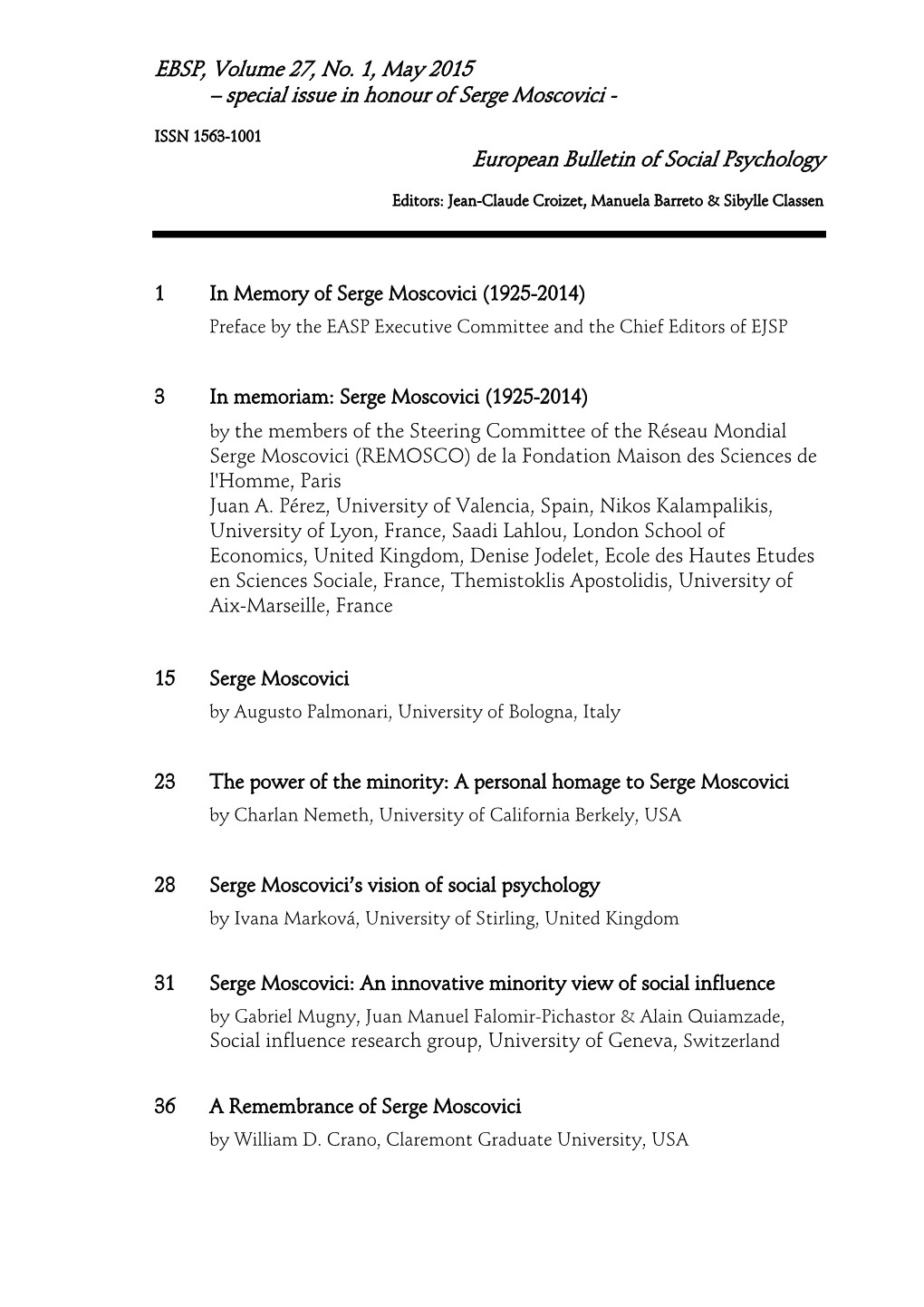

EBSP, Volume 27, No. 1, May 2015 – Special Issue in Honour of Serge Moscovici

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Symbols As Social History? Ten Preliminary Notes on the Image and Sign Systems of Social Movements in Germany

History of Symbols as Social History? Ten preliminary notes on the image and sign systems of social movements in Germany GOTTFRIED KORFF The last two centuries have produced, transformed and destroyed a myriad of political symbols of a linguistic, visual and ritual form. Between, say 1790 and 1990 the political sphere witnessed both an explosion in the generation of symbols and a radical decline of symbols. This calls for explanations. Mary Douglas and Serge Moscovici have provided insightful reflections on the theory and history of political symbols of modern social movements. In Moscovici the analysis of symbols is part of a political psychology which aims to interpret the behaviour and conceptions of nineteenth- and twentieth-century mass movements.1 Moscovici's basic premise is that, due to the emergence of new forms of collective conditions of existence, society's perception of itself has been determined since the French Revolu- tion by the image of the mass, by the concept of political mass movements. The extent of the revolutionary processes which determined and accom- panied the progress into modernity, and the political reaction following them, were defined by the category "mass" by those directly involved as well observers. The "mass" was not just a category but also a strategy: the "mass movement" and the "mass action" were seen as the goals of political action. Reaching this goal required collective representations in the form of linguistic, visual and ritual symbols. Signs, images and gestures created and consolidated collective -

Ethics in the Theory of Social Representations1

Papers on Social Representations Volume 22, pages 4.1-4.8 (2013) Peer Reviewed Online Journal ISSN 1021-5573 © 2013 The Authors [http://www.psych.lse.ac.uk/psr/] Ethics in the Theory of Social Representations1 IVANA MARKOVÁ University of Stirling There are different ways in which the question ‘what makes humans distinct from other species?’ can be answered. One way is to refer to the ability of humans to reason and make rational decisions; another is to point to the capacity of humans to speak and express themselves in symbols; or to imagine future events and be aware of their mortality; and so on. I propose to focus here on the capacity of humans to make ethical choices and to view this as a feature of common sense knowledge and to that extent, as a feature of the theory of social representations. MAKING ETHICAL CHOICES From his early years shaped by the Second World War, Nazism and Stalinism, Serge Moscovici has placed the study of ethical choices, values and social norms into the centre of his attention with regard to the meaning of humanity. As he reveals that in his autobiography Chronique des années égares, (Moscovici, 1997) in his early youth he found inspiration in Nietzsche’s philosophical thoughts, in Pascal’s Pensées and in Spinoza’s Ethics. In his autobiography Moscovici scrutinized passions that, throughout the long past of mankind, tore apart communities as well as brought them again together. Within broad historical and cultural contexts he pondered 1 This paper is a shortened version of a lecture presented at the 11th International Conference on Social Representations in Evora, June 2012. -

1 Terrorism As a Tactic of Minority Influence Arie W. Kruglanski University of Maryland Paper Presented at F. Buttera and J. Le

1 Terrorism as a Tactic of Minority Influence Arie W. Kruglanski University of Maryland Paper presented at F. Buttera and J. Levine (Chairs). Active Minorities: Hoping and Coping. April, 2003. Grenoble, France. 2 Since the late 1970s the topic of minority influence has been an important research issue for social psychologists. Introduced by Serge Moscovici’s seminal papers, minority influence research was itself an example of minority influence in that it innovated and deviated from the tendency to view social influence predominantly from the majority’s perspective. However, as Moscovici aptly pointed out, majority influence serves to preserve existing knowledge whereas the formation of new knowledge, germinating as it typically does in the mind of a single individual, or forged in a small group of persons presupposes the influence of a minority on a dominant majority. The typical metaphor for much of minority influence research was nonviolent influence conducted by the minority members through socially sanctioned means, such as debates, publications, appearances in the media, lawful protests and licensed public demonstrations conducted according to rules. And the prototypical cases of minority influence phenomena were innovations in science and technology, minority-prompted change in political attitudes, shifts in the world of fashion, etc. But in the several last decades a very different type of influence tactic has captivated the world’s attention and mobilized the world’s resources, going by the name of “terrorism” and considered by many the scourge of our times. Though a small groups of social scientists (primarily political scientists, sociologists, and psychiatrists) have been studying terrorism since the early 1970s, only the events of 9/11 catapulted the topic to the very top of everyone’s research agenda. -

Experiments in Intergroup Discrimination

Experiments in Intergroup Discrimination Can discrilnination be traced to SOlne such origin as social conflict or a history of hostility? Not necessarily. Apparently the lnere fact of division into groups is enough to trigger discriminatory behavior by Henri Tajfel ntergroup discrimination is a feature logical causation. In The Functions of ciocultural milieu. This convergence is of most modern societies. The phe Social Conflict, published in 1956, Lewis often considered in terms of social learn I nomenon is depressingly similar re A. Coser of Brandeis University estab ing and confOimity. For instance, there is gardless of the constitution of the "in lished a related dichotomy when he dis much evidence that children learn quite group" and of the "outgroup" that is per tinguished between two types of inter early the pecking order of evaluations of ceived as being somehow different. A group conflict: the "rational" and the "ir various groups that prevails in their so Slovene friend of mine once described to rational." The former is a means to an ciety, and that the order remains fairly me the stereotypes-the common traits end: the conflict and the attitudes that stable. This applies not only to the evalu attributed to a large human group-that go with it reflect a genuine competition ation of groups that are in daily contact, are applied in his country, the richest between groups with divergent interests. such as racial groups in mixed environ constituent republic of Yugoslavia, to The latter is an end in itself: it serves to ments, but also to ideas about foreign immigrant Bosnians, who come from a release accumulated emotional tensions nations with which there is little if any poorer region. -

Elites, Single Parties and Political Decision-Making in Fascist-Era Dictatorships

Elites, Single Parties and Political Decision-making in Fascist-era Dictatorships ANTOÂ NIO COSTA PINTO Italian Fascism and German National-Socialism were both attempts to create a charismatic leadership and `totalitarian tension' that was, in one form or another, also present in other dictatorships of the period.1 After taking power, both National-Socialism and Fascism became powerful instruments of a `new order', agents of a `parallel administration', and promoters of innumerable tensions within these dictatorial political systems. Transformed into single parties, they ¯ourished as breeding-grounds for a new political elite and as agents for a new mediation between the state and civil society, creating tensions between the single party and the state apparatus in the process.2 These tensions were responsible for the emergence of new centres of political decision-making that on the one hand led to the concentration of power in the hands of Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler, but also removed it from the government and the ministerial elite, who were often increasingly subordinated to the single party and its `parallel administration'. This article seeks to ascertain the locus of political decision-making authority, the composition and the recruitment channels of the dictatorships' ministerial elites during the fascist era. It will do so by examining three fundamental areas. The ®rst of these is charisma and political decision-making, that is, an examination of the characteristics of the relationships that existed between the dictators and their ministerial elites by studying the composition and structure of these elites, as well as the methods used in their recruitment and the role of the single parties in the political system and in the governmental selection process. -

Modern/Postmodern Political Conceptualization: Romania and Its Option

MODERN/POSTMODERN POLITICAL CONCEPTUALIZATION: ROMANIA AND ITS OPTION La definición de modernidad y postmodernidad política: la opción rumana Viorella MANOLACHE* Bucharest University Abstract The study confirms the author’s constant concerns to evaluate the modern /postmodern Romanian space, the transition effects and the involvement of the Romanian elite in (re)configuring a new political, economic, social and cultural profile. The article proposes a comparative picture, appealing to the postmodern versus rule: communism vs. postmodern, qualitative analysis vs. quantitative analysis, old elite vs. new elite. Without choosing to present hard and categorical conclusions, the study launches the large lines of the Romanian attempt to consort with Western political, economic, social and cultural perspective and to overcome blocking the canon. Key words: modernity, postmodernity, communism, post-communism, retro- institutionalization, transition to democracy, formal and informal institutions, old and new political, social, economic, cultural elite. Resumen Este estudio plantea un modelo de evaluación de la modernidad y posmodernidad rumana, los efectos de la transición y el papel de la elite rumana en la (re)configu- * Graduated Science Political Faculty, Law Faculty, has a master in Journalism and Public Relations and PhD. with a research theme concern with Romanian Political Elitism, Bucharest University. Assistant researcher at the Romanian Academy, Institute of the Political Science and International Relations, at the Department of Political Philosophy. Email: [email protected]. Fecha de recepción del artículo: 16 de diciembre de 2008. Fecha de aceptación: 5 de mayo de 2009. Versión final: 13 de diciembre de 2009. STVDIVM. Revista de Humanidades, 16 (2010) ISSN: 1137-8417, pp. 189-200 190 ][ Viorella MANOLACHE Modern/postmodern political conceptualization:… ración de un escenario político, económico, social y cultural nuevo. -

Cognitive Aspects of Prejudice

/. biosoc. Sci,, Suppl. 1 (1969), 173-191 COGNITIVE ASPECTS OF PREJUDICE HENRI TAJFEL Department of Psychology, University of Bristol Introduction The diffusion of public knowledge concerning laws which govern the physical, the biological and the social aspects of our world is neither peculiar to our times of mass communications nor to our own culture. These public images are as old as mankind, and they seem to have some fairly universal characteristics. The time of belief in a 'primitive mind' in other cultures has long been over in social anthro- pology. For example, at the turn of the century, Rivers (1905) could still write about differences in colour naming between the Todas and the Europeans in terms of the 'defective colour nomenclature of the lower races' (p. 392). Today, Claude Levi-Strauss (1966) bases much of his work on evidence showing the conceptual complexity of the understanding of the world in primitive cultures rooted in the 'science of the concrete' with its background of magic. As he wrote: To transform a weed into a cultivated plant, a wild beast into a domestic animal, to produce, in either of these, nutritious or technologically useful pro- cesses which were originally completely absent or could only be guessed at; to make stout water-tight pottery out of clay which is friable and unstable, liable to pulverise or crack; to work out techniques, often long and complex, which permit cultivation without soil or alternatively without water; to change toxic roots or seeds into foodstuffs or again to use their poison for hunting, war or ritual—there is no doubt that all these achievements required a genuinely scientific attitude, sustained and watchful interest, and a desire for knowledge for its own sake. -

Nationalism and Ethnic Politics When Politics and Social Theory Converge

This article was downloaded by: [Swets Content Distribution] On: 1 March 2010 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 912280237] Publisher Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37- 41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Nationalism and Ethnic Politics Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713636289 When Politics and Social Theory Converge: Group Identification and Group Rights in Northern Ireland Richard Jenkins a a University of Sheffield, To cite this Article Jenkins, Richard(2006) 'When Politics and Social Theory Converge: Group Identification and Group Rights in Northern Ireland', Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 12: 3, 389 — 410 To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/13537110600882619 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13537110600882619 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

Prejudice As Collective Definition: Ideology, Discourse and Moral Exclusion

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Loughborough University Institutional Repository Prejudice as Collective Definition: Ideology, Discourse and Moral Exclusion Cristian Tileaga Discourse and Rhetoric Group Loughborough University To appear in Antaki, C. and Condor, S. (Eds) Rhetoric, ideology and social psychology: Essays in honour of Michael Billig (Explorations in Social Psychology Series). London: Routledge 1 In Anti-Semite and Jew, Jean-Paul Sartre draws a portrait of the ‘anti-Semite’ as a sociopsychological type. Sartre’s portrait is not merely a description of a type, but a morality play, where the ‘anti-Semite’ is an actor on the scene of French society of the time. Although it is a particular portrait, general aspects of anti- Semitism as a tradition of persecution can be also identified in Sartre's account. There is a relevance here to social psychology. A parallel can be drawn between Sartre’s portrait of the anti-Semite and that of the ‘extremist’ offered by social psychologists. The ‘extremist’, like the ‘anti-Semite’, is a certain kind of person - someone who can be described by what he or she thinks, feels, and ultimately, does. In this chapter I want to offer a consideration of two philosophies by which we can understand the ‘extremist’. The first is a philosophy underpinned by social psychologists’ traditional efforts to conceptualize prejudice as a matter of personality and individual differences. The second - drawing gratefully on the work of Michael Billig - is a philosophy that accounts for prejudice as socio- communicative product. The two philosophies map onto two histories of prejudice. -

The Communist Propagandistic Model: Towards a Cultural Genealogy Cioflâncă, Adrian

www.ssoar.info The communist propagandistic model: towards a cultural genealogy Cioflâncă, Adrian Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Cioflâncă, A. (2010). The communist propagandistic model: towards a cultural genealogy. Studia Politica: Romanian Political Science Review, 10(3), 447-482. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-446622 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de The Communist Propagandistic Model 447 The Communist Propagandistic Model Towards A Cultural Genealogy∗ ADRIAN CIOFLÂNCĂ The communist state is often labeled by scholars a ”propaganda-state”1. The explanation for this stays with the prevailing role of mass communication and indoctrination, which constantly defined the relation between the regime and the society at large. The communist regime granted propaganda a central position, thus turning it into a valuable mean to achieve radical ends: the total transformation of the society and the creation of a ”new man”. Consequently, massive, baroque, arborescent propaganda outfits were institutionally developed. Furthermore, the verbalization of ideology became a free-standing profession for millions of people all over Eastern Europe2. In other words, the communist political culture turned the propaganda effort consubstantial with the act of governing, with the results of the latest being often judged from the standpoint of the propagandistic performances. -

Jean-Jacques Thomas Romance Languages and Literatures University at Buffalo

Jean-Jacques Thomas Romance Languages and Literatures University at Buffalo Isidore Isou’s spirited letters It is paradoxical to consider that today Isidore Isou, probably one of the least known Romanian-born French writers and philosophers could be the most famous and the best considered Romanian intellectual of the twentieth century. It is probably his insatiable desire for public fame and recognition that prevented him from achieving such a possible destiny at least at par with Tristan Tzara or Eugène Ionesco. An extremely well-read intellectual, an indefatigable writer and thinker, there are very few aspects of human knowledge, be they letters, arts or sciences that, at one point or another in his life, did not attract his intellectual attention and his knowledgeable study. Totally convinced of his own worth and of his own exceptional nature, in several essays he compares his nature and intellectual status to that of Leonardo da Vinci, estimating even that his own capacity to construct a unified system of organization of human knowledge placed him above da Vinci who could only systematize and understand fragmentary aspects of human knowledge.1 For many of his contemporaries, it is this hubris (megalomania) coupled with a sharp and relentless criticism of the mediocrity of the other intellectuals, writers and thinkers of the immediate post WWII period in France that explains Isou’s paradoxical status as a marginal intellectual generally at odds with different intellectual and literary movements that span the 1945-1970 period in France. Two terms are directly related to his early literary accomplishments and innovations: Letterism [lettrisme] and metagraphy [métagraphie]. -

Catalogue 2017- 2018 (A Selection of Publications)

Catalo gue A Selection of Publications (presented in English) Éditions de l’École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales Catalogue 2017-2018 (a selection of publications) Éditions de l’École des hautes études en sciences sociales 105, bd Raspail – 75006 Paris – France Tel.: 33 (0)1 53 63 51 00 – Fax: 33 (0)1 44 07 08 89 [email protected] – www.editions.ehess.fr ÉDITIONS DE L’ÉCOLE 105, bd Raspail • 75006 Paris • France DES HAUTES ÉTUDES Tel.: 33 (0)1 53 63 51 00 • Fax: 33 (0)1 44 07 08 89 EN SCIENCES SOCIALES [email protected] • www.editions.ehess.fr Editorial director: Emmanuel Désveaux [email protected] General manager: Jean-Baptiste Boyer [email protected] Press representative: Milène Veyrier [email protected] • Tel.: 33 (0)1 53 10 53 63 Foreign rights/International development: Anne Madelain • [email protected] Tel.: 33 (0)1 53 10 53 85 Sales France CDE: Centre de diffusion de l’édition (except series mentioned below) 17, rue de Tournon • 75006 Paris • France Tel.: +33 (0)1 44 41 19 19 • Fax: +33 (0)1 44 41 19 14 Sales Foreign Gallimard Export/Sodis (except series mentioned below) 5, rue Gaston-Gallimard • 75328 Paris Cedex 07 • France Tel.: +33 (0)1 49 54 14 53 • Fax: +33 (0)1 49 54 14 95 Email: [email protected] Suisse: Office du livre de Fribourg Canada: Socadis Not distributed by CDE and Gallimard Export u Collection “Hautes Études” and journal L’Homme: Volumen/Seuil Tel.: 33 (0)1 69 10 89 35 • Fax: 33 (0)1 64 48 49 63 u Collection “Contextes”: diffusion Vrin Tel.: 33 (0)1 43 54 03 47 • Fax: 33 (0)1 43 54 48 13 Email: [email protected] u Serie Grief: Dalloz/UP Diffusion Tel.: 33 (0)1 40 46 49 20 • Email: [email protected] u Journal Annales.