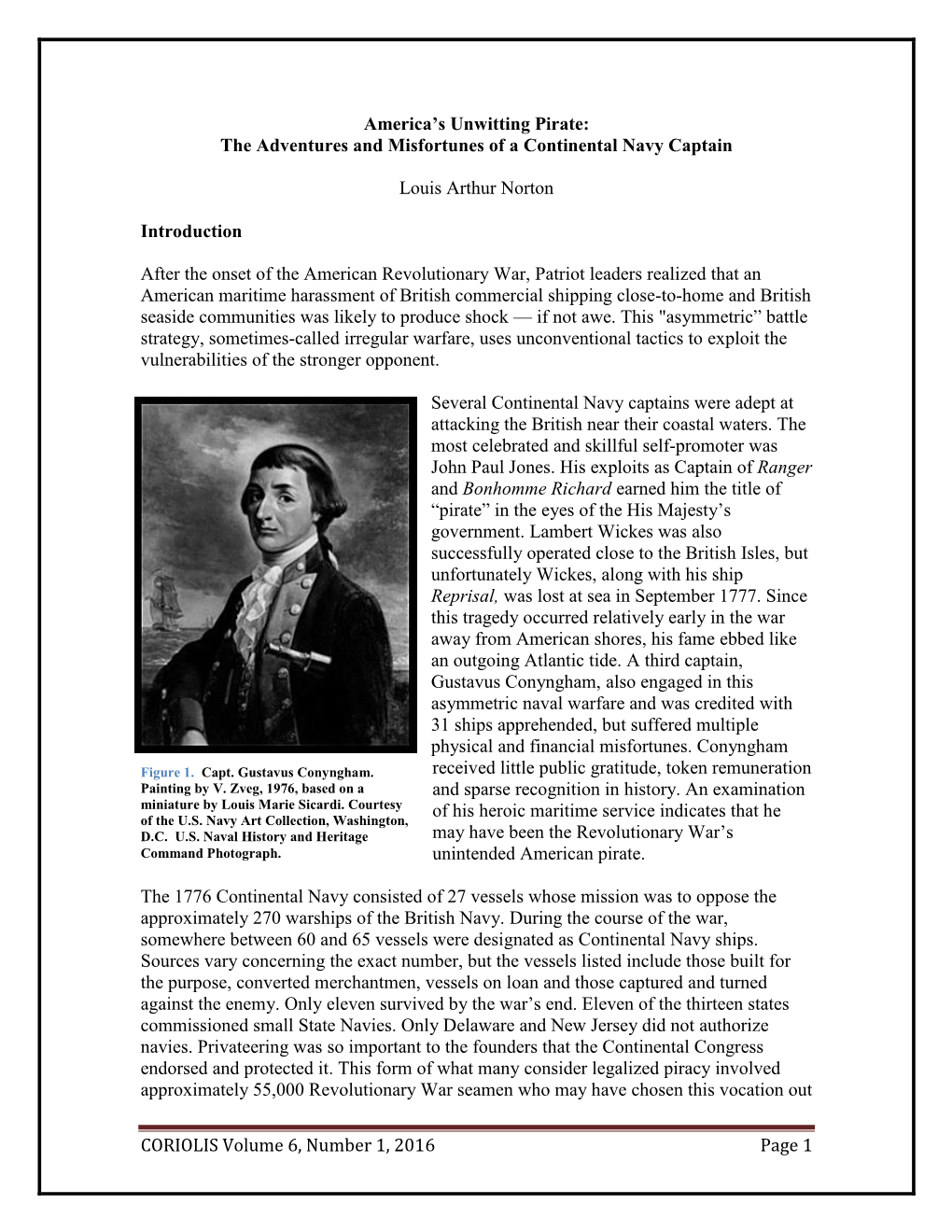

CORIOLIS Volume 6, Number 1, 2016 Page 1 America's Unwitting Pirate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Symbolism of Commander Isaac Hull's

Presentation Pieces in the Collection of the USS Constitution Museum Silver Urn Presented to Captain Isaac Hull, 1813 Prepared by Caitlin Anderson, 2010 © USS Constitution Museum 2010 What is it? [Silver urn presented to Capt. Isaac Hull. Thomas Fletcher & Sidney Gardiner. Philadelphia, 1813. Private Collection.](1787–1827) Silver; h. 29 1/2 When is it from? © USS Constitution Museum 2010 1813 Physical Characteristics: The urn (known as a vase when it was made)1 is 29.5 inches high, 22 inches wide, and 12 inches deep. It is made entirely of sterling silver. The workmanship exhibits a variety of techniques, including cast, applied, incised, chased, repoussé (hammered from behind), embossed, and engraved decorations.2 Its overall form is that of a Greek ceremonial urn, and it is decorated with various classical motifs, an engraved scene of the battle between the USS Constitution and the HMS Guerriere, and an inscription reading: The Citizens of Philadelphia, at a meeting convened on the 5th of Septr. 1812, voted/ this Urn, to be presented in their name to CAPTAIN ISAAC HULL, Commander of the/ United States Frigate Constitution, as a testimonial of their sense of his distinguished/ gallantry and conduct, in bringing to action, and subduing the British Frigate Guerriere,/ on the 19th day of August 1812, and of the eminent service he has rendered to his/ Country, by achieving, in the first naval conflict of the war, a most signal and decisive/ victory, over a foe that had till then challenged an unrivalled superiority on the/ ocean, and thus establishing the claim of our Navy to the affection and confidence/ of the Nation/ Engraved by W. -

Spanish, French, Dutch, Andamerican Patriots of Thb West Indies During

Spanish, French, Dutch, andAmerican Patriots of thb West Indies i# During the AMERICAN Revolution PART7 SPANISH BORDERLAND STUDIES By Granvil~ W. andN. C. Hough -~ ,~~~.'.i~:~ " :~, ~i " .... - ~ ,~ ~"~" ..... "~,~~'~~'-~ ,%v t-5.._. / © Copyright ,i. "; 2001 ~(1 ~,'~': .i: • by '!!|fi:l~: r!;.~:! Granville W. and N. C. Hough 3438 Bahia Blanca West, Apt B ~.l.-c • Laguna Hills, CA 92653-2830 !LI.'.. Email: gwhough(~earthiink.net u~ "~: .. ' ?-' ,, i.. Other books in this series include: • ...~ , Svain's California Patriots in its 1779-1783 War with England - During the.American Revolution, Part 1, 1998. ,. Sp~fin's Califomi0 Patriqts in its 1779-1783 Wor with Englgnd - During the American Revolution, Part 2, :999. Spain's Arizona Patriots in ire |779-1783 War with Engl~n~i - During the Amcricgn RevolutiQn, Third Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 1999. Svaln's New Mexico Patriots in its 1779-|783 Wit" wi~ England- During the American Revolution, Fourth Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 1999. Spain's Texa~ patriot~ in its 1779-1783 War with Enaland - Daring the A~a~ri~n Revolution, Fifth Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 2000. Spain's Louisi~a Patriots in its; 1779-1783 War witil England - During.the American Revolution, Sixth StUdy of the Spanish Borderlands, 20(~0. ./ / . Svain's Patriots of Northerrt New Svain - From South of the U. S. Border - in its 1779- 1783 War with Engl~nd_ Eighth Study of the Spanish Borderlands, coming soon. ,:.Z ~JI ,. Published by: SHHAK PRESS ~'~"'. ~ ~i~: :~ .~:,: .. Society of Hispanic Historical and Ancestral Research ~.,~.,:" P.O. Box 490 Midway City, CA 92655-0490 (714) 894-8161 ~, ~)it.,I ,. -

Alumni News & Notes

et al.: Alumni News & Notes and hosted many Homecoming Weekend here are students who maintain strong activities. "The goals of SUSA include pro T ties to Syracuse University after they viding leadership roles for students, pro graduate. Then there are students like viding career and mentoring opportuni Naomi Marcus 'o2. Just beginning her col ties for students, connecting and network lege career, she has already established a ing with Syracuse alumni, and maintain bond with the SU alumni community. ing traditions and a sense of pride in Marcus is an active member of the Syra Syracuse University," says Setek. cuse University Student Alumni Associa Danie Moss '99 says taking an active tion (SUSA}, a student volunteer organiza role in Homecoming Weekend was a mile tion sponsored by the Office of Alumni Re stone for SUSA. She and past SUSA presi lations that serves as a link between students dent Kristin Kuntz '99 saw it as a good way and the University's 22o,ooo alumni. to promote the organization. "Home For Marcus and her fellow student vol coming is a great opportunity for us to unteers, SUSA's appeal lies in its ability to interact with alumni," Moss says. "People bridge generations. "It sounded like a dif don't always realize how much they can ferent kind of organization," Marcus says. learn from other generations, so an organi "Alumni share their experiences with us, zation like this is mutually beneficial." WITH GRATITUDE AND RESPECT and we keep them up-to-date on what's Senior Alison Nathan has been pleas "Thank you"- two simple words that going on here right now. -

2010 Regular Session

HJ 14 Department of Legislative Services Maryland General Assembly 2010 Session FISCAL AND POLICY NOTE Revised House Joint Resolution 14 (Delegate Walkup) Rules and Executive Nominations Recognition of Captain Lambert Wickes of Maryland - Revolutionary War Naval Hero This joint resolution requests the Maryland General Assembly to recognize the role of Captain Lambert Wickes of Maryland in the successful outcome of the American Revolutionary War. The State must partner with the United States Navy to develop and conduct an appropriate memorial event on the grounds of the United States Naval Academy annually on October 1 to honor the service and sacrifice of Captain Lambert Wickes. Fiscal Summary State Effect: Conducting a memorial event for Captain Lambert Wickes will not affect State finances. Local Effect: None. Small Business Effect: None. Analysis Background: Lambert Wickes was born around 1742 in Kent County, Maryland. During the Revolutionary War, Wickes was appointed as the captain of the 16-gun Reprisal and listed as the eleventh in seniority in the Continental Navy. In October 1776 Wickes was selected to transport Benjamin Franklin to France on a secret mission. Through this mission, Wickes became the first Continental Navy Officer to enter European waters and the Reprisal was the first American warship to base operations in Europe, capturing and destroying 14 ships in five days. On the ships return voyage to the United States, the Reprisal sunk in the Atlantic Ocean during a violent storm. Wickes, along with the men onboard the Reprisal perished. Only one member of the ship’s crew survived. Despite his contributions to the Continental Navy, Wickes did not receive a military burial, or a State or national commemoration for his sacrifice. -

The Life of Silas Talbot, a Commodore in the Navy of the United States

•' %/ .i o LIFE OF TALBOT THE LIFE OF SILAS TALBOT COMMODORE IN THE NAVY OF THE UNITED STATES, BY HENRY T. TUCKERMAN. NEW-YORK: I C. RIKER, 129 FULTON-STREET. 1850. ETgoT Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1850, by H. T. TUCKERMAN, in the Clerk's Office of the Southern District of New-York. John F. Trow, Printer, 49 Ann-st., N. Y. PREFACE The following memoir was intended for the series of American Biography edited by- President Sparks. Owing to the suspension of that valuable work, and at the suggestion of its accomplished editor, the present sketch appears in a separate volume. In preparing it, I have been actuated by a desire to ren- der justice to a highly efficient and patriotic American officer, and, at the same time, to preserve some of the incidents and corre- spondence which belong to that period of our country's annals, to which the flight of time only adds new significance and interest. There has been manifest, until within a few 1* VI PREFACE. years, a singular indifference to the histori- cal and biographical details of our revolu- tionary era ; and an absence of that cordial recognition of individual merit in some of the chief actors of that great drama, which confirm, not only the proverbial charge of ingratitude against republics, but justify De Tocqueville's theory with regard to their exclusive devotion to the immediate, and their peculiar insensibility to the lessons of the past. The difficulty experienced in ob- taining many of the facts in this brief and imperfect sketch, as well as the original documents requisite to authenticate them, is sufficient evidence of the forgetfulness and neglect to which the records of American public characters are liable. -

Draft Chapter

Ocean Special Area Management Plan Chapter 4: Cultural and Historic Resources Table of Contents 400 Introduction ......................................................................................................................3 410 Historic Contexts and Cultural Landscapes of the Ocean SAMP Area .......................4 410.1 Pre-Contact Geological History............................................................................5 410.2 Narragansett Tribal History.................................................................................6 410.3 European Exploration and Colonial Settlement Landscape Context .............16 410.4 Post-Colonial Cultural Landscape Context.......................................................18 410.5 Military Landscape Context ...............................................................................21 410.6 Fisheries Landscape Context ..............................................................................31 410.6.1 Rhode Island Fisheries.............................................................................31 410.6.2 Fishing and Subsistence on Block Island.................................................33 410.6.3 Historic Shipwrecks of Fishing Vessels ..................................................34 410.6.4 Historic Harbor Features..........................................................................35 410.7 Marine Transportation and Commercial Landscape Context ........................35 410.8 Recreation and Tourism Landscape Context....................................................38 -

2013 Fall NL

PENNSYLVANIA SOCIETY OF SONS OF THE REVOLUTION www.amrev.org VOLUME 23 NUMBER 3 FALL 2013 A Celebration of Independence Superintendent Cynthia Younger Members MacLeod of Independence National Historic Park Reception welcomed us all on this festive day, as members September 12, 2013 -- Following the PSSR’s of the Orpheus Club Choir Board of Managers meeting, the Society’s provided spirited patriotic Younger Members Committee hosted a music. In addition, Michael Cocktails with the Board reception at the Quinn, president and CEO of Bachelors Barge Club on Boathouse Row. the Museum of the American Revolution (MAR) spoke A full turnout of younger members and about the unique nature of board members enjoyed cocktails, cigars Philadelphia in the broad and a sumptuous spread from our friends at scope of the Revolution, Di Bruno Bros. And despite the signature and left us with anticipation cocktails, and the weather, being Dark & for the forthcoming soon- Stormy, a great time was had by all. to-be-relocated museum moving to just two blocks THE TRADITION CONTINUES from Independence Hall. For the forty-fourth consecutive year, the Pennsylvania Society celebrated “Let Freedom Ring” at Independence National Historical Park on July 4th in Philadelphia. A capacity gathering of Society members, families and guests met at the Sheraton Society Hill in Philadelphia and were Richard Pagano, John Ventura and Harvard Wood welcomed by cocktails and a sumptuous luncheon. Following the event at the boathouse, many of the younger members continued on to After lunch, the Color Guard, led by Captain a popular speakeasy in center city for an Robert Van Gulick, paraded from Society Finally, just prior to the 2 pm annual impromptu mixer with our friends the Young Hill, through Philadelphia’s Historic District Liberty Bell ringing ceremony, we were Dames of the NSCDA. -

![Adair, John]: MANUSCRIPT WRIT DATED APRIL 29, 1799](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8221/adair-john-manuscript-writ-dated-april-29-1799-1718221.webp)

Adair, John]: MANUSCRIPT WRIT DATED APRIL 29, 1799

Item No. 1 Crockett Flees the Jurisdiction! 1. [Adair, John]: MANUSCRIPT WRIT DATED APRIL 29, 1799. JOHN ADAIR COMPLAINS THAT JOHN CROCKETT HAS FLED THE COUNTY, OWING ADAIR ONE HUNDRED GUINEAS. JUSTICE OF THE PEACE GABRIEL SLAUGHTER ORDERS THE SHERIFF OF MERCER COUNTY, WHERE BOTH ADAIR AND CROCKETT RESIDE, TO SEIZE CROCKETT'S ESTATE TO PAY THE DEBT. [Mercer County, KY: April 29, 1799]. Folio, single leaf 7.5" x 12.5", partly untrimmed. Completely in neat ink manuscript, signed by Gabl. Slaughter, docketed on verso. Light age toning, old folds. Very Good. John Adair [1757-1840], eighth Governor of Kentucky, fought in the Northwest Indian War, was a United States Congressman and a delegate to Kentucky's Constitutional Conventions of 1792 and 1799. Suspected of complicity with Aaron Burr, he lost his bid for a full term in the U.S. Senate in 1806; Adair was later acquitted. [Kleber: KENTUCKY ENCYCLOPEDIA, 1992.] Gabriel Slaughter [1767-1830], born in Culpeper County Virginia, moved to Kentucky in 1791. He was a Justice of the Peace of Mercer County and Kentucky's seventh Governor from 1816-1820. [Id. 825.] John Crockett belonged to the Kentucky branch of the Crockett family [Davy Crockett's father was a different John Crockett]. $500.00 Item No. 2 The Thriving, Illegal African Slave Trade 2. [African Slave Trade]: CORRESPONDENCE WITH SPAIN, PORTUGAL, BRAZIL, THE NETHERLANDS, SWEDEN, AND THE ARGENTINE CONFEDERATION, RELATIVE TO THE SLAVE TRADE. FROM JANUARY 1 TO DECEMBER 31, 1841, INCLUSIVE. PRESENTED TO BOTH HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT BY COMMAND OF HER MAJESTY, 1842. London: Printed by William Clowes and Sons, 1842. -

View the James Sever Collection Finding Aid Here

Finding Aid For James Sever Collection USS Constitution Museum Collection [2506.1] © 2021 USS Constitution Museum | usscm.org Finding Aid James Sever Collection, 1764-1801 Summary Information Title: James Sever Collection Inclusive Dates: 1764 - 1801 Extent: 0.63 linear feet Catalog Number: 2506.1 Language of Materials: English Repository: USS Constitution Museum Processed by: Kate Monea, 2021 Access and Use Access Restrictions Records are unrestricted. Copyright Copyright status is unknown. Citation USS Constitution Museum Collection. Acquisition and Provenance The USS Constitution Museum purchased the collection at auction in 2020. Previously, the collection was descended through the Sever family in private hands for over a century. Biographical Sketch James Sever was one of the six founding captains of the U.S. Navy, and the first captain of the frigate USS Congress. Sever was born in Kingston, Massachusetts in 1761. He graduated from Harvard College in 1781 and was commissioned an ensign in the Continental Army that year. He rose to the rank of lieutenant, serving until 1794. After the American Revolution, Sever worked as a merchant ship captain, but he had no previous naval experience when he was appointed in 1794 as construction superintendent and future captain of USS Congress in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. He lost the position when construction on USS Congress was suspended in 1796, following peace with Algiers. In 1798, as the Quasi-War with France was heating up, Sever was recalled and appointed to command the 20-gun ship USS Herald. When construction of USS Congress was 1 USS Constitution Museum Finding Aid completed and the ship was launched in August 1799, Sever was returned to command of that frigate. -

•A Maritime History of the United States

The Eagle’s Webbed Feet The Eagle’s Webbed Feet •A Maritime History ofA theMaritime United History ofStates the United States A Maritime History • The United States is a maritime nation • What does that mean? (83125 vs. 7514) • Course themes: • The United States has always depended on the navy for its power and status (or lack thereof) • The history of the Navy very much aligns with the history of the Nation. What We’re Going to Do • Revolution and the Demise of the Navy • Build a “New Navy” To Defend a New Country • More Wars & other tasks (The Civil War) • Second Demise and Creation of another “New Navy” • Transition from a Great Power to a Super Power Navy • A Super Power’s Navy in the Cold War and beyond Opening Comments • Strategy and Doctrine • Questions, Questions, Questions • Facts vs. Opinions • My apologies to: • The Marines • The Merchant Marine • The Coast Guard Your instructor is biased! Revolution and the Demise of the Navy “It follows as certain as night succeeds the day, that without a decisive naval force we can do nothing definitive – and with it everything honorable and glorious.” “I have not yet begun to fight!” 18th Century Warships • Classification • Tactics • 44 verses 74, etc.: • The weather gage • Decks • The aim point • Rating • Raking • The Line • Guns • Frigates • Throw weight • Range • Strategy • Guerre d’escadre • Guerre de course • Letters-of-Marque Weather Gauge Raking American Maritime Advantages • Coastal trade dominated communications • Shipbuilding (1/3 of all English ships at ½ the cost) • Lots of experienced builders, sailors & captains • World wide traders, fisherman, & whalers. -

Saratoga Sannois San Sebatian Saint-Quentin Saint-Martory Saint-Germain-En-Laye Saint Petersburg Saarlouis Saarland Royal Tunbri

William Franklin William Strahan Jane Mecom Mary Hewson [To Lord Kames] Henry Home To William Franklin To William Franklin To Lord Kames Coventry To Sir Alexander Dick West Wycombe Sir Alexander Dick Thomas Cushing Joseph Smith Noble Wimberly Jones Burlington To Mary Stevenson Prestonfield To William Franklin: Journal of Negotiations in London To Sir Alexander Dick Wanstead Richard Jackson To Lord Kames To [Joseph Smith?] Humphry Marshall To Joseph SmithTo WilliamTo FranklinWilliam Franklin Edinburgh To William Franklin Peter Collinson New Jersey Assembly Committee of Correspondence To William Franklin To JosephTo JosephSmith SmithTo WilliamTo WilliamFranklin Franklin William Robertson To William Franklin To William Franklin To WilliamTo FranklinWilliam FranklinJohn Canton To William Franklin To William Franklin Duns To William Franklin To William Franklin William Cullen To William FranklinTo WilliamTo WilliamFranklin Franklin To Lord Kames Liverpool To Sir Alexander Dick To Lord KamesTo Lord Kames To William FranklinTo William Franklin To William Franklin To William FranklinTo William FranklinTo William Franklin To Sir AlexanderTo Dick Sir Alexander Dick To William Franklin To Lord Kames To William FranklinTo William FranklinTo William Franklin Peter P. Burdett West Bradford To Sir Alexander Dick To the ToNew Lord Jersey Kames Assembly Committee ofTo Correspondence William FranklinTo William Franklin To Lord KamesTo Lord Kames To William Franklin To Mary Stevenson To William FranklinTo William FranklinTo William Franklin To Mary StevensonTo -

FSU ETD Template

Florida State University Libraries 2015 Cut from Different Cloth: The USS Constitution and the American Frigate Fleet Richard Brownlow Byington Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES CUT FROM DIFFERENT CLOTH: THE USS CONSTITUTION AND THE AMERICAN FRIGATE FLEET By RICHARD BROWNLOW BYINGTON A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2015 Richard Byington defended this dissertation on October 9, 2015. The members of the supervisory committee were: Rafe Blaufarb Professor Directing Dissertation Candace Ward University Representative Jonathan Grant Committee Member Maxine Jones Committee Member Nathan Stoltzfus Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii In Loving Memory of Clarice Rippl (1915-2012) iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the guidance and help of several individuals that in one way or another contributed in the preparation and completion of this study. First and foremost I would like to offer my most sincere gratitude to my major professor, Dr. Rafe Blaufarb. Most assuredly, Dr. Blaufarb will never fully comprehend the impact he had on me throughout my academic career. Accepting me into the graduate program at Florida State University opened doors that I presumed would remain closed forever. I would also like to thank my PhD committee members, Drs. Jonathan Grant, Maxine Jones, Nathan Stoltzfus, and Candace Ward for taking the time to read the first draft of my dissertation and give valuable insight into raising the level of my writing.