The Northern Mariner / Le Marin Du Nord XVIII

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spanish, French, Dutch, Andamerican Patriots of Thb West Indies During

Spanish, French, Dutch, andAmerican Patriots of thb West Indies i# During the AMERICAN Revolution PART7 SPANISH BORDERLAND STUDIES By Granvil~ W. andN. C. Hough -~ ,~~~.'.i~:~ " :~, ~i " .... - ~ ,~ ~"~" ..... "~,~~'~~'-~ ,%v t-5.._. / © Copyright ,i. "; 2001 ~(1 ~,'~': .i: • by '!!|fi:l~: r!;.~:! Granville W. and N. C. Hough 3438 Bahia Blanca West, Apt B ~.l.-c • Laguna Hills, CA 92653-2830 !LI.'.. Email: gwhough(~earthiink.net u~ "~: .. ' ?-' ,, i.. Other books in this series include: • ...~ , Svain's California Patriots in its 1779-1783 War with England - During the.American Revolution, Part 1, 1998. ,. Sp~fin's Califomi0 Patriqts in its 1779-1783 Wor with Englgnd - During the American Revolution, Part 2, :999. Spain's Arizona Patriots in ire |779-1783 War with Engl~n~i - During the Amcricgn RevolutiQn, Third Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 1999. Svaln's New Mexico Patriots in its 1779-|783 Wit" wi~ England- During the American Revolution, Fourth Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 1999. Spain's Texa~ patriot~ in its 1779-1783 War with Enaland - Daring the A~a~ri~n Revolution, Fifth Study of the Spanish Borderlands, 2000. Spain's Louisi~a Patriots in its; 1779-1783 War witil England - During.the American Revolution, Sixth StUdy of the Spanish Borderlands, 20(~0. ./ / . Svain's Patriots of Northerrt New Svain - From South of the U. S. Border - in its 1779- 1783 War with Engl~nd_ Eighth Study of the Spanish Borderlands, coming soon. ,:.Z ~JI ,. Published by: SHHAK PRESS ~'~"'. ~ ~i~: :~ .~:,: .. Society of Hispanic Historical and Ancestral Research ~.,~.,:" P.O. Box 490 Midway City, CA 92655-0490 (714) 894-8161 ~, ~)it.,I ,. -

2010 Regular Session

HJ 14 Department of Legislative Services Maryland General Assembly 2010 Session FISCAL AND POLICY NOTE Revised House Joint Resolution 14 (Delegate Walkup) Rules and Executive Nominations Recognition of Captain Lambert Wickes of Maryland - Revolutionary War Naval Hero This joint resolution requests the Maryland General Assembly to recognize the role of Captain Lambert Wickes of Maryland in the successful outcome of the American Revolutionary War. The State must partner with the United States Navy to develop and conduct an appropriate memorial event on the grounds of the United States Naval Academy annually on October 1 to honor the service and sacrifice of Captain Lambert Wickes. Fiscal Summary State Effect: Conducting a memorial event for Captain Lambert Wickes will not affect State finances. Local Effect: None. Small Business Effect: None. Analysis Background: Lambert Wickes was born around 1742 in Kent County, Maryland. During the Revolutionary War, Wickes was appointed as the captain of the 16-gun Reprisal and listed as the eleventh in seniority in the Continental Navy. In October 1776 Wickes was selected to transport Benjamin Franklin to France on a secret mission. Through this mission, Wickes became the first Continental Navy Officer to enter European waters and the Reprisal was the first American warship to base operations in Europe, capturing and destroying 14 ships in five days. On the ships return voyage to the United States, the Reprisal sunk in the Atlantic Ocean during a violent storm. Wickes, along with the men onboard the Reprisal perished. Only one member of the ship’s crew survived. Despite his contributions to the Continental Navy, Wickes did not receive a military burial, or a State or national commemoration for his sacrifice. -

2013 Fall NL

PENNSYLVANIA SOCIETY OF SONS OF THE REVOLUTION www.amrev.org VOLUME 23 NUMBER 3 FALL 2013 A Celebration of Independence Superintendent Cynthia Younger Members MacLeod of Independence National Historic Park Reception welcomed us all on this festive day, as members September 12, 2013 -- Following the PSSR’s of the Orpheus Club Choir Board of Managers meeting, the Society’s provided spirited patriotic Younger Members Committee hosted a music. In addition, Michael Cocktails with the Board reception at the Quinn, president and CEO of Bachelors Barge Club on Boathouse Row. the Museum of the American Revolution (MAR) spoke A full turnout of younger members and about the unique nature of board members enjoyed cocktails, cigars Philadelphia in the broad and a sumptuous spread from our friends at scope of the Revolution, Di Bruno Bros. And despite the signature and left us with anticipation cocktails, and the weather, being Dark & for the forthcoming soon- Stormy, a great time was had by all. to-be-relocated museum moving to just two blocks THE TRADITION CONTINUES from Independence Hall. For the forty-fourth consecutive year, the Pennsylvania Society celebrated “Let Freedom Ring” at Independence National Historical Park on July 4th in Philadelphia. A capacity gathering of Society members, families and guests met at the Sheraton Society Hill in Philadelphia and were Richard Pagano, John Ventura and Harvard Wood welcomed by cocktails and a sumptuous luncheon. Following the event at the boathouse, many of the younger members continued on to After lunch, the Color Guard, led by Captain a popular speakeasy in center city for an Robert Van Gulick, paraded from Society Finally, just prior to the 2 pm annual impromptu mixer with our friends the Young Hill, through Philadelphia’s Historic District Liberty Bell ringing ceremony, we were Dames of the NSCDA. -

Navies and Soft Power Historical Case Studies of Naval Power and the Nonuse of Military Force NEWPORT PAPERS

NAVAL WAR COLLEGE NEWPORT PAPERS 42 NAVAL WAR COLLEGE WAR NAVAL Navies and Soft Power Historical Case Studies of Naval Power and the Nonuse of Military Force NEWPORT PAPERS NEWPORT 42 Bruce A. Elleman and S. C. M. Paine, Editors U.S. GOVERNMENT Cover OFFICIAL EDITION NOTICE The April 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil-rig fire—fighting the blaze and searching for survivors. U.S. Coast Guard photograph, available at “USGS Multimedia Gallery,” USGS: Science for a Changing World, gallery.usgs.gov/. Use of ISBN Prefix This is the Official U.S. Government edition of this publication and is herein identified to certify its au thenticity. ISBN 978-1-935352-33-4 (e-book ISBN 978-1-935352-34-1) is for this U.S. Government Printing Office Official Edition only. The Superinten- dent of Documents of the U.S. Government Printing Office requests that any reprinted edition clearly be labeled as a copy of the authentic work with a new ISBN. Legal Status and Use of Seals and Logos The logo of the U.S. Naval War College (NWC), Newport, Rhode Island, authenticates Navies and Soft Power: Historical Case Studies of Naval Power and the Nonuse of Military Force, edited by Bruce A. Elleman and S. C. M. Paine, as an official publica tion of the College. It is prohibited to use NWC’s logo on any republication of this book without the express, written permission of the Editor, Naval War College Press, or the editor’s designee. For Sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402-00001 ISBN 978-1-935352-33-4; e-book ISBN 978-1-935352-34-1 Navies and Soft Power Historical Case Studies of Naval Power and the Nonuse of Military Force Bruce A. -

GNM Silent Killers.Qxd:Layout 1

“A truly engrossing chronicle.” Clive Cussler JAMES P. DELGADO SILENT KILLERS SUBMARINES AND UNDERWATER WARFARE FOREWORD BY CLIVE CUSSLER © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com SUBMARINES AND UNDERWATER WARFARE JAMES P. DELGADO With a foreword by Clive Cussler © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CONTENTS Foreword 6 Author’s Note 7 Introduction: Into the Deep 11 Chapter 1 Beginnings 19 Chapter 2 “Sub Marine Explorers”: Would-be Warriors 31 Chapter 3 Uncivil Warriors 45 Chapter 4 Missing Links 61 Chapter 5 Later 19th Century Submarines 73 Chapter 6 Transition to a New Century 91 Chapter 7 Early 20th Century Submariness 107 Chapter 8 World War I 123 Chapter 9 Submarines Between the Wars 143 Chapter 10 World War II: the Success of the Submarine 161 Chapter 11 Postwar Innovations: the Rise of Atomic Power 189 Chapter 12 The Ultimate Deterrent: the Role of the 207 Submarine in the Modern Era Chapter 13 Memorializing the Submarine 219 Notes 239 Sources & Select Bibliography 248 Index 260 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com FOREWORD rom the beginning of recorded history the inhabitants of the earth have had a Fgreat fascination with what exists under the waters of lakes, rivers, and the vast seas. They also have maintained a great fear of the unknown and very few wished to actually go under the surface. In the not too distant past, they had a morbid fear and were deeply frightened of what they might find. Only three out of one hundred old-time sailors could swim because they had no love of water. -

Full Spring 2004 Issue the .SU

Naval War College Review Volume 57 Article 1 Number 2 Spring 2004 Full Spring 2004 Issue The .SU . Naval War College Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Naval War College, The .SU . (2004) "Full Spring 2004 Issue," Naval War College Review: Vol. 57 : No. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol57/iss2/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Naval War College: Full Spring 2004 Issue N A V A L W A R C O L L E G E NAVAL WAR COLLEGE REVIEW R E V I E W Spring 2004 Volume LVII, Number 2 Spring 2004 Spring N ES AV T A A L T W S A D R E C T I O N L L U E E G H E T R I VI IBU OR A S CT MARI VI Published by U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons, 2004 1 Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen Naval War College Review, Vol. 57 [2004], No. 2, Art. 1 Cover A Landsat-7 image (taken on 27 July 2000) of the Lena Delta on the Russian Arctic coast, where the Lena River emp- ties into the Laptev Sea. The Lena, which flows northward some 2,800 miles through Siberia, is one of the largest rivers in the world; the delta is a pro- tected wilderness area, the largest in Rus- sia. -

•A Maritime History of the United States

The Eagle’s Webbed Feet The Eagle’s Webbed Feet •A Maritime History ofA theMaritime United History ofStates the United States A Maritime History • The United States is a maritime nation • What does that mean? (83125 vs. 7514) • Course themes: • The United States has always depended on the navy for its power and status (or lack thereof) • The history of the Navy very much aligns with the history of the Nation. What We’re Going to Do • Revolution and the Demise of the Navy • Build a “New Navy” To Defend a New Country • More Wars & other tasks (The Civil War) • Second Demise and Creation of another “New Navy” • Transition from a Great Power to a Super Power Navy • A Super Power’s Navy in the Cold War and beyond Opening Comments • Strategy and Doctrine • Questions, Questions, Questions • Facts vs. Opinions • My apologies to: • The Marines • The Merchant Marine • The Coast Guard Your instructor is biased! Revolution and the Demise of the Navy “It follows as certain as night succeeds the day, that without a decisive naval force we can do nothing definitive – and with it everything honorable and glorious.” “I have not yet begun to fight!” 18th Century Warships • Classification • Tactics • 44 verses 74, etc.: • The weather gage • Decks • The aim point • Rating • Raking • The Line • Guns • Frigates • Throw weight • Range • Strategy • Guerre d’escadre • Guerre de course • Letters-of-Marque Weather Gauge Raking American Maritime Advantages • Coastal trade dominated communications • Shipbuilding (1/3 of all English ships at ½ the cost) • Lots of experienced builders, sailors & captains • World wide traders, fisherman, & whalers. -

Saratoga Sannois San Sebatian Saint-Quentin Saint-Martory Saint-Germain-En-Laye Saint Petersburg Saarlouis Saarland Royal Tunbri

William Franklin William Strahan Jane Mecom Mary Hewson [To Lord Kames] Henry Home To William Franklin To William Franklin To Lord Kames Coventry To Sir Alexander Dick West Wycombe Sir Alexander Dick Thomas Cushing Joseph Smith Noble Wimberly Jones Burlington To Mary Stevenson Prestonfield To William Franklin: Journal of Negotiations in London To Sir Alexander Dick Wanstead Richard Jackson To Lord Kames To [Joseph Smith?] Humphry Marshall To Joseph SmithTo WilliamTo FranklinWilliam Franklin Edinburgh To William Franklin Peter Collinson New Jersey Assembly Committee of Correspondence To William Franklin To JosephTo JosephSmith SmithTo WilliamTo WilliamFranklin Franklin William Robertson To William Franklin To William Franklin To WilliamTo FranklinWilliam FranklinJohn Canton To William Franklin To William Franklin Duns To William Franklin To William Franklin William Cullen To William FranklinTo WilliamTo WilliamFranklin Franklin To Lord Kames Liverpool To Sir Alexander Dick To Lord KamesTo Lord Kames To William FranklinTo William Franklin To William Franklin To William FranklinTo William FranklinTo William Franklin To Sir AlexanderTo Dick Sir Alexander Dick To William Franklin To Lord Kames To William FranklinTo William FranklinTo William Franklin Peter P. Burdett West Bradford To Sir Alexander Dick To the ToNew Lord Jersey Kames Assembly Committee ofTo Correspondence William FranklinTo William Franklin To Lord KamesTo Lord Kames To William Franklin To Mary Stevenson To William FranklinTo William FranklinTo William Franklin To Mary StevensonTo -

1840-1900 People Who Have Drowned

PEOPLE WHO HAVE DROWNED IN THE FALKLAND ISLANDS From 1840 to 1900 NB: There are many more that drowned off and around the Islands in total shipwrecks but details were not been recorded; the following represent those found at time of research. 1840-1849 1843: Thomas AGGOTT, age abt 20. Drowned. 1843: George PIKE, age 20. Drowned with Thomas AGGOTT. 1845 Sep 17: Richard PENNY, age 43, seaman on board the schooner Reunion. Drowned. 1845 Sep 17: James HALLORAN, age not recorded, seaman on board the schooner Reunion. Drowned. 1845 Sep 17: Francois GRENARDE, age not recorded, seaman of Reunion. Found drowned. 1845 Sep 17: Allain CAMP, age not recorded, seaman of Reunion. Found drowned. 1845 Sep 17: Edmond KEMP, age 25, seaman of Reunion. Found drowned. 1845 Oct 30: (date buried) Carmelita PENNY, age not recorded, widow of R Penny. Found drowned. 1846 Feb 12: (date buried) George BURNS, age 25, seaman of Stanley. Found drowned. 1846 Feb 12: (date buried) John NIBBS alias EDMONDS, age 27, seaman of Stanley. Found drowned. 1848 Jan 02: (date buried) William A BROWN, age 23, American of Stanley. Drowned sealing (W SMITH was drowned with him) 1848 Jan: William SMITH. Body not found. Drowned sealing with William A BROWN. 1840-1849 27 people died – 44% from drowning 1850-1859 1852 Sep 02: George GARCIA, age abt 28, gaucho, drowned accidentally out of a boat. 1854 May 02: (date buried) Charles ROBINSON, age 27, seaman ship Perseverance of Stanley, drowned 1855 Mar 14: Augustus Charles PLOGER, age abt 34, Seaman & a native of the United States of America, Accidentally drowned. -

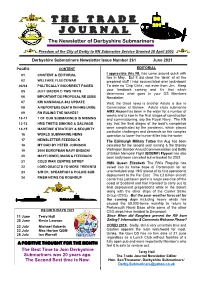

The Trade Journal Newsletter Editor the Second Best Time Is Now

DS T H E T R A D E 261 9 JOURNAL Freedom of the City of Derby to RN Submarine Service Granted 28 April 2002 Derbyshire Submariners Newsletter Issue Number 261 June 2021 EDITORIAL PAGE/S CONTENT 01 CONTENT & EDITORIAL I appreciate this NL has come around quick with two in May. But it did clear the ‘deck’ of all the 02 WELFARE FLEECEWAR prepared stuff I had accumulated over lock-down! 03/04 POLITICALLY INCORRECT PAGES To date no ‘Drip Chits’, not even from Jim. Keep 05 JEFF BACON © TWO TIFFS your feedback coming and it’s that which determines what goes in your DS Members 06 IMPORTANT DS PROPOSAL RE SUBS Newsletter. 07 KRI NANGGALA 402 UPDATE Well, the Good news is another Astute is due to 08 A REPORTERS DEATH ON HMS URGE Commission at Barrow. Astute class submarine 09 RN RULING THE WAVES? HMS Anson has been in the water for a number of weeks and is now in the final stages of construction 10-11 1 OF OUR SUBMARINES IS MISSING and commissioning, say the Royal Navy. The RN 12-13 HMS THETIS SINKING & SALVAGE say that the final stages of the boat’s completion 14-15 MARITIME STRATEGY & SECURITY were complicated by the pandemic, which placed particular challenges and demands on the complex 16 WORLD SUBMARINE NEWS operation to lower the hunter-killer into the water. 17 NEWSLETTER FEEDBACK The Edinburgh Military Tattoo this Aug has been 18 MY DAD BY PETER JOHNSON cancelled for the second year running & the Stanley 19 2004 EUROPEAN NAVY ENSIGN! Wellington Bomber Annual Commemoration and Battle of Britain Memorial Flight (BOBMF) Flypast has also 20 MAYFLOWER, MAGS & FEEDBACK been sadly been cancelled but re-booked for 2022. -

Book Reviews

BOOK REVIEWS The Legend of the Founding Fathers. By WESLEY FRANK CRAVEN. [Anson G. Phelps Lectureship on Early American History, New York University, Stokes Foundation.] (New York: New York University Press, 1956. [viii], 191 p. Index. JS4.50.) Originally delivered as a series of lectures, these urbane and careful essays examine several questions that have not previously called forth the effort required to understand them. Mr. Craven's own field of research has decided the shape and urgency of some of his queries. He has been determined, for example, to find a more satisfying answer than those at hand as to why the founding fathers of New England have been given more attention than the founding fathers of Virginia. He is similarly concerned about the tendency to obscure the earliest colonial leaders with images of the founding fathers of the Revolutionary era. From such questions he moves to the considera- tion of the growth of these legends and the uses of history down to our own time. The volume is the fruit not only of years of study and thought about early American history, but also of much specific research into the reflec- tions of that history in more recent American society. The annotations to the six chronological chapters which comprise the book form something of a guide to this material. The author shows particular interest in early state and national histories, but also uses sermons, patriotic speeches, records of immigrant and patriotic societies, the writings of Revolutionary leaders, and even the debunking writings of the years before the second World War. -

Shipwreck and Salvage in the Tropics: the Case of HMS Thetis, 1830–1854

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Birkbeck Institutional Research Online Birkbeck ePrints BIROn - Birkbeck Institutional Research Online Enabling open access to Birkbeck’s published research output Shipwreck and salvage in the tropics: the case of HMS Thetis, 1830–1854 Journal Article http://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/4118 Version: Author’s Final (Refereed) Citation: Driver, F.; Martins, L. (2006) Shipwreck and salvage in the tropics: the case of HMS Thetis, 1830- 1854 – Journal of Historical Geography 32(3), pp. 539-562 © 2006 Elsevier Publisher version ______________________________________________________________ All articles available through Birkbeck ePrints are protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. ______________________________________________________________ Deposit Guide Contact: [email protected] Shipwreck and Salvage in the Tropics: The Case of HMS Thetis, 1830-1854 Draft of an article published in Journal of Historical Geography 32:3 (2006), 539-562. Authors Felix Driver and Luciana Martins Address Felix Driver Department of Geography Royal Holloway, University of London Egham Surrey TW20 0EX [email protected] Luciana Martins School of Languages, Linguistics and Culture Birkbeck, University of London 43 Gordon Square London WC1H 0PD [email protected] Shipwreck and Salvage in the Tropics: The Case of HMS Thetis, 1830-1854 Abstract In 1830, the British frigate HMS Thetis was wrecked at Cabo Frio, on the Brazilian coast. A British naval force was subsequently despatched to undertake a major salvage operation which lasted for well over a year. The substantial textual and visual archive associated with the case of the Thetis raises wider questions about the entanglement of naval, scientific, artistic, financial and legal concerns in an age of British maritime expansion.