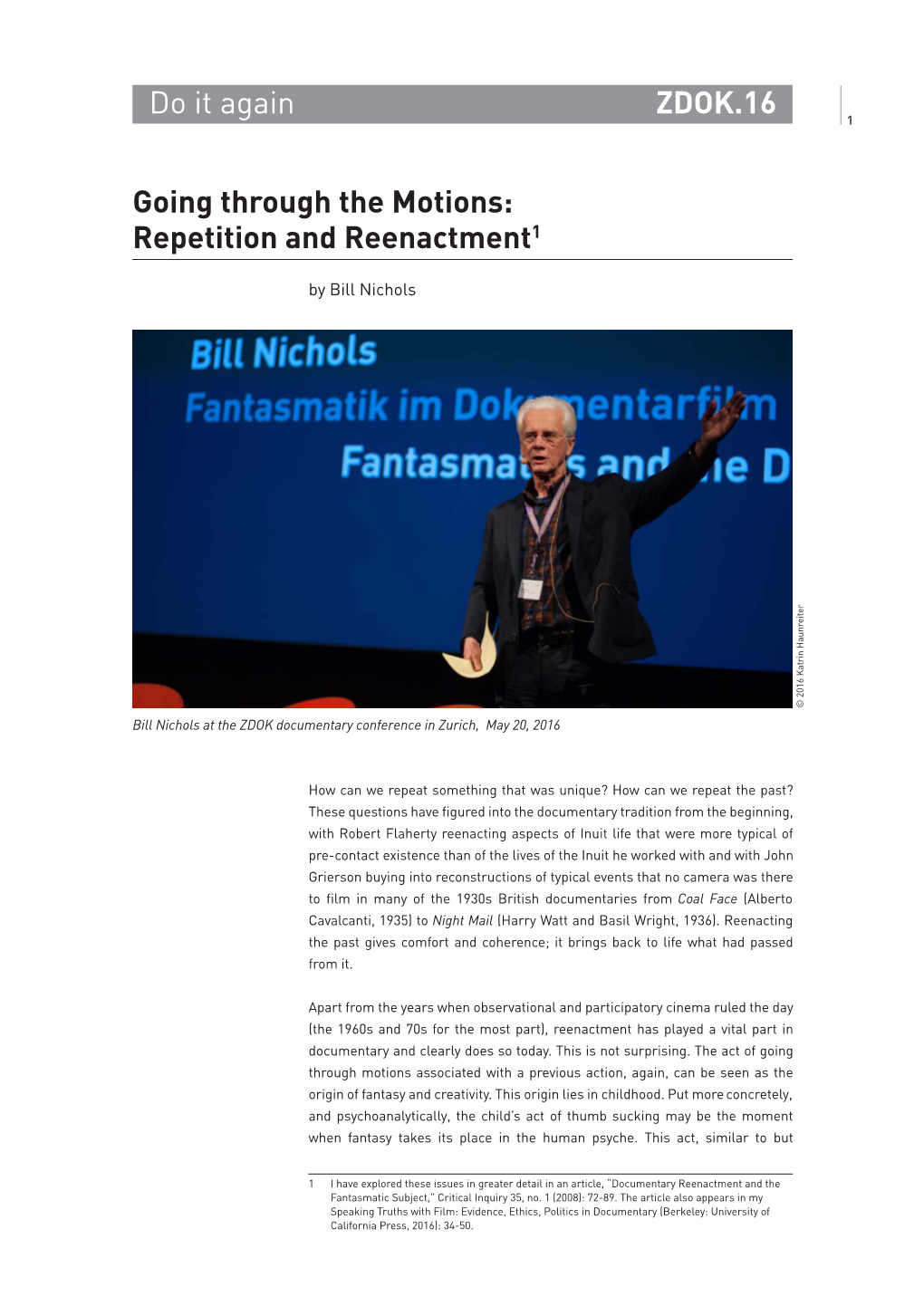

Do It Again ZDOK.16 Going Through the Motions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Torture and the Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment of Detainees: the Effectiveness and Consequences of 'Enhanced

TORTURE AND THE CRUEL, INHUMAN AND DE- GRADING TREATMENT OF DETAINEES: THE EFFECTIVENESS AND CONSEQUENCES OF ‘EN- HANCED’ INTERROGATION HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON THE CONSTITUTION, CIVIL RIGHTS, AND CIVIL LIBERTIES OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION NOVEMBER 8, 2007 Serial No. 110–94 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://judiciary.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 38–765 PDF WASHINGTON : 2008 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Aug 31 2005 15:46 Jul 29, 2008 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 H:\WORK\CONST\110807\38765.000 HJUD1 PsN: 38765 COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY JOHN CONYERS, JR., Michigan, Chairman HOWARD L. BERMAN, California LAMAR SMITH, Texas RICK BOUCHER, Virginia F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER, JR., JERROLD NADLER, New York Wisconsin ROBERT C. ‘‘BOBBY’’ SCOTT, Virginia HOWARD COBLE, North Carolina MELVIN L. WATT, North Carolina ELTON GALLEGLY, California ZOE LOFGREN, California BOB GOODLATTE, Virginia SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas STEVE CHABOT, Ohio MAXINE WATERS, California DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California WILLIAM D. DELAHUNT, Massachusetts CHRIS CANNON, Utah ROBERT WEXLER, Florida RIC KELLER, Florida LINDA T. SA´ NCHEZ, California DARRELL ISSA, California STEVE COHEN, Tennessee MIKE PENCE, Indiana HANK JOHNSON, Georgia J. RANDY FORBES, Virginia BETTY SUTTON, Ohio STEVE KING, Iowa LUIS V. GUTIERREZ, Illinois TOM FEENEY, Florida BRAD SHERMAN, California TRENT FRANKS, Arizona TAMMY BALDWIN, Wisconsin LOUIE GOHMERT, Texas ANTHONY D. -

Approvement the Analysis of Dieter Dengler's Defense Mechanism in Rescue Dawn Movie English Letters Department Letters And

APPROVEMENT THE ANALYSIS OF DIETER DENGLER’S DEFENSE MECHANISM IN RESCUE DAWN MOVIE A Thesis Submitted to Letters and Humanities Faculty in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for By: Woro Endah Sitoresmi 105026000921 Approved By: Advisor, Mohammad Supardi, S.S. ENGLISH LETTERS DEPARTMENT LETTERS AND HUMANITIES FACULTY STATE ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY “SYARIF HIDAYATULLAH” JAKARTA 2008 i ABSTRACT Woro Endah Sito Resmi, “The Analysis of Dieter Dengler’s Defense Mechanism in Rescue Dawn Movie”. Skripsi. Jakarta: Letters and Humanities Faculty, State Islamic University Syarif Hidayatullah, July 2008. The paper examines Dieter Dengler’s defense mechanism in surviving process from the Vietcong jail as the main character in Rescue Dawn movie. The paper looks at one problem: How are Dieter Dengler’s surviving process viewed from the concept of defense mechanism. The objective of the research is intended to describe Dieter Dengler’s defense mechanism in surviving process from the jail that implied in this movie. This movie is analyzed carefully and accurately using the theory of Sigmund Freud’s Psychoanalysis; it is Ego defense mechanism concept. The data on this research are got from the unit of analysis, the sources, and the analysis from the writer. As it is fulfilled, the writer finds out that Dieter applied his defense mechanism through Eros instinct, fantasy, repression, format reaction, rationalization and sublimation. His defense mechanism becomes the power which leads and dominates all of his actions in order to get the freedom. ii LEGALIZATION A thesis entitled “The analysis of Dieter Dengler’s Defense Mechanism in Rescue Dawn movie” has been defended before the Letters and Humanities Faculty’s Examination Committee on October, 16 2008. -

The Forgotten Americans of the Vietnam War

Prisoners of War The Forgotten Americans of the Vietnam War By Louis R. Stockstill On the following pages you will find one of the most saddening. But death and wounds are irretrievable, and important articles ever published in this magazine. Tell- all we can do is to make suitable provision for the ing you this may seem redundant. If an article is unim- wounded and the survivors of the dead. The prisoners, portant, we should not be publishing it at all. At the on the other hand, are alive and are retrievable. We can same time, we have always acknowledged to ourselves do something about them. We must. that not all readers are interested in everything we print. The author, who has done such a thorough and pains- Our job is to supply a balanced buffet table—not in- taking job, served for many years on the staff of The travenous feeding. Journal of the Armed Forces, ultimately as its Editor. But the matter of our American servicemen who have Lou Stockstill has devoted his professional life to the sacrificed their freedom, their health, and the peace of examination and explanation of the problems of the mind of themselves and their families in behalf of free- armed forces of the United States. He is now a free- dom for others—this is a matter that concerns us all. lance writer in Washington. This article represents, in By the hundreds, these men languish in North Vietnam our judgment, the finest effort of his distinguished ca- prisons and in Viet Cong jungle camps—unprotected by reer. -

BIMJ February 2012

Supplementary Text BLACKBURN & PENGIRAN TENGAH. Brunei Int Med J. 2012; 8 (1):60-61 (i) General History Laos has a long history of being conquered and ruled by several ancient empires (Khmer, Burmese and Siam). It was a mon- archy for most of the last 700 years, ruled from the ancient capital of Luang Prabang, which is now on the UNESCO World Heritage list. Laos (along with Vietnam and Cambodia forming Indochina) came under French rule at the end of the 19 th century. The French established their capital in Viang Chan, re-spelling it Vientiane. The French system of Vietnam-centric administration with rural taxation led to resentment and small-scale rebel- lions. During, and following World War II a nationalist movement began, divided between three groups: pro-monarchy, pro democracy and communist. The last was known as the Pathet Lao (Land of Lao) and had links with the Indochinese Commu- nist party founded by Ho Chi Minh in 1930. The Cold War between the Communist Soviet Union and the West- ern democracies also played out in Indochina. Initially France tried to retain its colonies but as the Indochina Wars (predominantly between Vietnam and France but involving Laos) demoralised and defeated the French, the United States of America (USA) entered the fray. The USA supplied millions of dollars of aid to Laos, partly with the aim of preventing the spread of Communism from China through Southeast Asia. A second Laos interim government (formed in 1958) fell after only 8 months after the USA stopped aid because the Pathet Lao were included in the government. -

331 Marolda Voiceover: This Program Is Sponsored by the United States Naval Institute

331 Marolda Voiceover: This program is sponsored by the United States Naval Institute. (Theme music) Voiceover: The following is a production of the Pritzker Military Museum and Library. Bringing citizens and citizen soldiers together through the exploration of military history, topics, and current affairs, this is Pritzker Military Presents. (Applause) Williams: Welcome to Pritzker Military Presents with editor Edward J. Marolda discussing his book, Combat at Close Quarters: An Illustrated History of the US Navy in the Vietnam War. I’m your host Jay Williams, and this program is coming to you from the Pritzker Military Museum and Library in downtown Chicago. It’s sponsored by the US Naval Institute. This program and hundreds more are available on demand at PritzkerMilitary.org. The enormous scale of land operations in the Vietnam War and the focus of the news media on land campaigns often leads us to forget that America’s direct military involvement in Vietnam was significantly escalated by the result of a conflict at sea. In August 1964 evidence suggested that North Vietnamese torpedo boats attacked two US Navy destroyers, the USS Maddox and USS Turner Joy, patrolling near their coast in the Gulf of Tonkin. This prompted the United States to immediately rapidly ramp up its involvement on the Vietnamese Peninsula. Throughout the Vietnam War the US Navy played a major role in important combat missions, including air operations, coastal surveillance, surface gun fire support, and logistics. With a total of 1.8 million sailors serving in Southeast Asia during the conflict, the navy provided the US Military with key strategic support to conduct extensive campaigns both from the air and on land by controlling the seas, by direct attack, and by standing as a constant reminder of American military might. -

From: Reviews and Criticism of Vietnam War Theatrical and Television Dramas ( Compiled by John K

From: Reviews and Criticism of Vietnam War Theatrical and Television Dramas (http://www.lasalle.edu/library/vietnam/FilmIndex/home.htm) compiled by John K. McAskill, La Salle University ([email protected]) R3712 RESCUE DAWN (USA, 2006) Credits: director/writer, Werner Herzog. Cast: Christian Bale, Steve Zahn, Jeremy Davies, Marshall Bell. Summary: War/action film set in Laos in the 1960s. Follows the real-life story of U.S. fighter pilot Dieter Dengler (Bale), a German-American shot down and captured in Laos during the Vietnam War. Dengler then organized the successful escape of a small band of POWs. “Bale loved chaotic filming with German director” WENN entertainment news wire service (Nov 6, 2006) Felperin, Leslie. “Rescue dawn” Variety 404/5 (Sep 18-24, 2006), p. 65-6. Goldstein, Gregg. “MGM to the ‘Rescue’ at Toronto fest” Hollywood reporter 396 (Dep 11, 2006), p. 1, 22. Goslawski, Barbara. “Rescue dawn” Box office 142/11 (Nov 2006), p. 102, 104. Hill, Logan. “Dark and lovely; The brooding Christian Bale works his strange Hollywood magic” New York (Oct 23, 2006), p. “Rescue dawn” Official web site viewed May 2006: (http://www.gibraltarfilms.com/projects/rescuedawn/#) Shown at various film festivals since Sept. 2006 but not scheduled for limited release in the U.S. until July 4, 2007 (c.f. Internet Movie Database) Schruers, Fred. “Movies; Three from the dark side; here comes trouble; Christian Bale lays on the complexity intently, one borrowed obsession at a time” Los Angeles times (Nov 12, 2006), Sunday calendar, p. E1. Smith, Gavin. “Feast of famine?” Film comment 42/6 (Nov/Dec 2006), p. -

(Self-)Reflexivity and Repetition in Documentary

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version UNSPECIFIED UNSPECIFIED Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) thesis, UNSPECIFIED. DOI Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/87147/ Document Version UNSPECIFIED Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Subjectivity, (Self-)reflexivity and Repetition in Documentary Silke Panse PhD-Thesis 2007 Film Studies School of Drama, Film and the Visual Arts University of Kent Canterbury Abstract This thesis advances a deterritorialised reading of documentary on several levels: firstly, with respect to the difference between non-fiction and fiction, allowing for a fluctuation between both. As this thesis examines the movements of subjective documentary between self-reflexivity and reflexivity, it argues against an understanding of reflexivity as something that is emotionally distanced from its object and thus relies on a strict separation from both the subject and what it documents, such as for instance the stable irony in many found footage or mock-documentaries. -

058 Smokejumper Issue 058 J

The National Smokejumper Quarterly Magazine SmokejumperAssociation January 2008 Ever Have a Fire with Jerry Daniels?.................................................5 A Tribute to Pilot Jim Larkin .........................................................12 A Critique of Rescue Dawn ............................................................23 CONTENTS Message from Message from the President ......................... 2 Idaho Needs to Welcome the Morgans Home 3 the President Elections for NSA ......................................... 3 Were You Ever on a Fire with Jerry Daniels? 5 Odds and Ends ............................................. 6 of our soul. We are jumpers, active or not. The reality is that the next jump by Fire Information .......................................... 8 any one of these young jumpers could Jumper Ingenuity in Alaska, 1961 ................ 9 bring them into their definition of the Spotting ..................................................... 10 ranks of the NSA. A Tribute to Jim Larkin-Forest Service Pilot 12 I was very fortunate not being in- A “Friends-Helping-Friends” Request ........ 14 jured thru 535 jumps, often feeling New NSA Life Members Since January 2007 14 bulletproof just like a lot of the young The View from Outside the Fence ............... 15 jumpers. However, that could have Jumping the Steens .................................... 16 been altered at any jump. So, those Ted Dethlefs Collection Centerfold ............ 18 that think the NSA is just for those John E. “Jack” Nash-Another Pioneer Jumper outside the ranks of the active, please 20 rethink that concept and accept the Russian Smokejumper Ivan Alexandrovich by Doug Houston fact that we all are one, bonded by the Novik ................................................... 21 (Redmond ’73) smokejumping experiences of the past, If It Could Go Wrong, It Did! ...................... 22 PRESIDENT present, and the future. It’s all good. A Critique of the Movie Rescue Dawn ........ -

I Remember Gene Debruin by Lee Gossett (Redding '57) Gene and I First Met in Seattle in the Spring of 1961. the Alaska Smokejump

I Remember Gene DeBruin by Lee Gossett (Redding '57) Gene and I first met in Seattle in the spring of 1961. The Alaska smokejumpers were told to report to Boeing Field where the Bureau of Land Management DC-3 would pick up the crew and fly us to Fairbanks. Memory tells me that there were about 16 of us gathered on that dreary May morning in the old terminal building. Many of us were returning Alaska jumpers and knew each other, but there were a couple of new jumpers on the roster in 1961. One of the new jumpers was Gene DeBruin (MSO-59), a quiet fellow about my size, 5' 8". As we were all shaking hands and renewing friendships around the cafe table, I remember the waitress coming over to take our orders. She then went to the next table to wait on the fellow seated there and he said, "I'm with those guys." I turned around, shook Gene's hand, and introduced myself and the other jumpers. That was my first time to meet Gene. Gene had jumped in Missoula prior to coming to Alaska and prior to that had been in the U.S. Air Force. He had attended the University in Missoula and graduated with, I think, a degree in forestry. I'm not sure what drew Gene to smokejumping, but perhaps attending the forestry school at the University had something to do with it. There were many jumpers there. Our flight to Fairbanks took all day with at least two fuel stops. When we arrived at Fairbanks, a local newspaper photographer was there to greet us, and we all posed for a photo with the DC-3. -

Copyrighted Material

1 Herzog and Auteurism Performing Authenticity Brigitte Peucker Michel Ichat ’ s Victoire sur l ’ Annapurna (1953) is incomplete, André Bazin tells the reader of “Cinema and Exploration,” because an avalanche “snatched the camera out of the hands of [Maurice] Herzog” (1967: 162). Bazin ’ s description conjures up a film camera immersed in snow, its lens obscured. No act of photographic registration can take place here: there is no distance between the hapless camera and its object. Struggling to delineate cinematic realism, Bazin evokes a limit case in bringing the real into the film frame, one in which the camera seized by an avalanche figures the collapse of world with filmic apparatus. Its existential weight intensified by its unrepresentability, Maurice Herzog ’ s peak experience is sublime. It ’ s the explorer ’ s brush with death that evokes Bazin ’ s central metaphor for the indexical image: the Veil of Veronica “pressed to the face of human suffering” (1967: 163). I have long suspected that Bazin ’ s account is what inspired Werner Stipetić to change his name to Werner Herzog, perhaps also to assume his particular aesthetic stance, since Bazin ’ s story contains all the lineaments of the portrait Herzog draws of himself as auteur. It ’ s the portrait of someone for whom the conquering of a mountain is co-extensive with filming it, for whom filmmaking demands a physical investment, and landscapes produce essential images because death lurks in the natural world. Most centrally, it ’ s the portrait of a filmmaker for whom authenticity is at stake. But what is the nature of this “authenticity”? It doesn ’ t reside in Bazinian realism in a strict sense, although it ’ s connected to its more metaphorical, expanded expression. -

RESCUE DAWN Synopsis

PRODUCTION NOTES RESCUE DAWN Synopsis In the annals of history’s great escapes there is no other story like that of Dieter Dengler, the only American to ever break out of a POW camp in the impenetrable Laotian jungle. After months plotting his getaway and a death-defying journey through some of the world’s fiercest wilderness, Dengler appeared at his first press conference looking like a dashing movie star and showing neither sentimentality nor bitterness – simply an indomitable will to survive that allowed him to triumph against impossible odds. Now, from legendary director Werner Herzog (GRIZZLY MAN, FITZCARROLDO) and starring acclaimed actor Christian Bale (BATMAN BEGINS, THE PRESTIGE) comes the incredible true story of a renegade who, from the depths of total darkness, blazed his own willful path to freedom. A blistering adventure and a stark epic of survival, RESCUE DAWN reveals how Dieter Dengler relied on the most primal qualities of evasion, endurance, tenacity and courage to find his way home. Dieter (BALE) had dreamed of flying since his childhood in wartime Germany. The only place he ever wanted to be was in the sky, but now, on his very first top-secret mission over Laos, the ace aviator’s plane is shot down to earth. Trapped in an impassable jungle far from U.S. control, Dengler is soon captured by notoriously dangerous Pathet Lao soldiers. Though he quickly realizes he is in the most terrifying and vulnerable of circumstances, he never gives an inch. After a shocking initial ordeal, he is taken to a small Laotian prison camp, where he meets two American soldiers already held captive for a stultifying two years – both nearly broken in spirit. -

Viet Nam Generation, Volume 4, Number Article 1 1-2

Vietnam Generation Volume 4 Number 1 Viet Nam Generation, Volume 4, Number Article 1 1-2 4-1992 Viet Nam Generation, Volume 4, Number 1-2 Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/vietnamgeneration Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation (1992) "Viet Nam Generation, Volume 4, Number 1-2," Vietnam Generation: Vol. 4 : No. 1 , Article 1. Available at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/vietnamgeneration/vol4/iss1/1 This Complete Volume is brought to you for free and open access by La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vietnam Generation by an authorized editor of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Viet Nam Generation, Volume 4, Number 1-2 Cover Page Footnote Edited by Dan Duffy. Contributing editors: Renny Christopher. David DeRose, Alan Farrell. Cynthia Fuchs, William M. King. Bill Shields, Tony Williams, and David Willson. This complete volume is available in Vietnam Generation: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/vietnamgeneration/vol4/iss1/1 Viet N am Generation A Journal of Recent History and Contemporary Issues Volume A Number 1-2 David Luebke illustrations, from the Vietnam Generation, Inc. & Burning Cities Press reprint of Asa Baber's novel, Land of a Million Elephants. Contents In This Is s u e ........................................................................................ 5 Poetry by Rod McQuearey.................................................... 79 PublishER's Sta tem en t.................................................................4