A Very Short Introduction to Gliding for Power Pilots

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

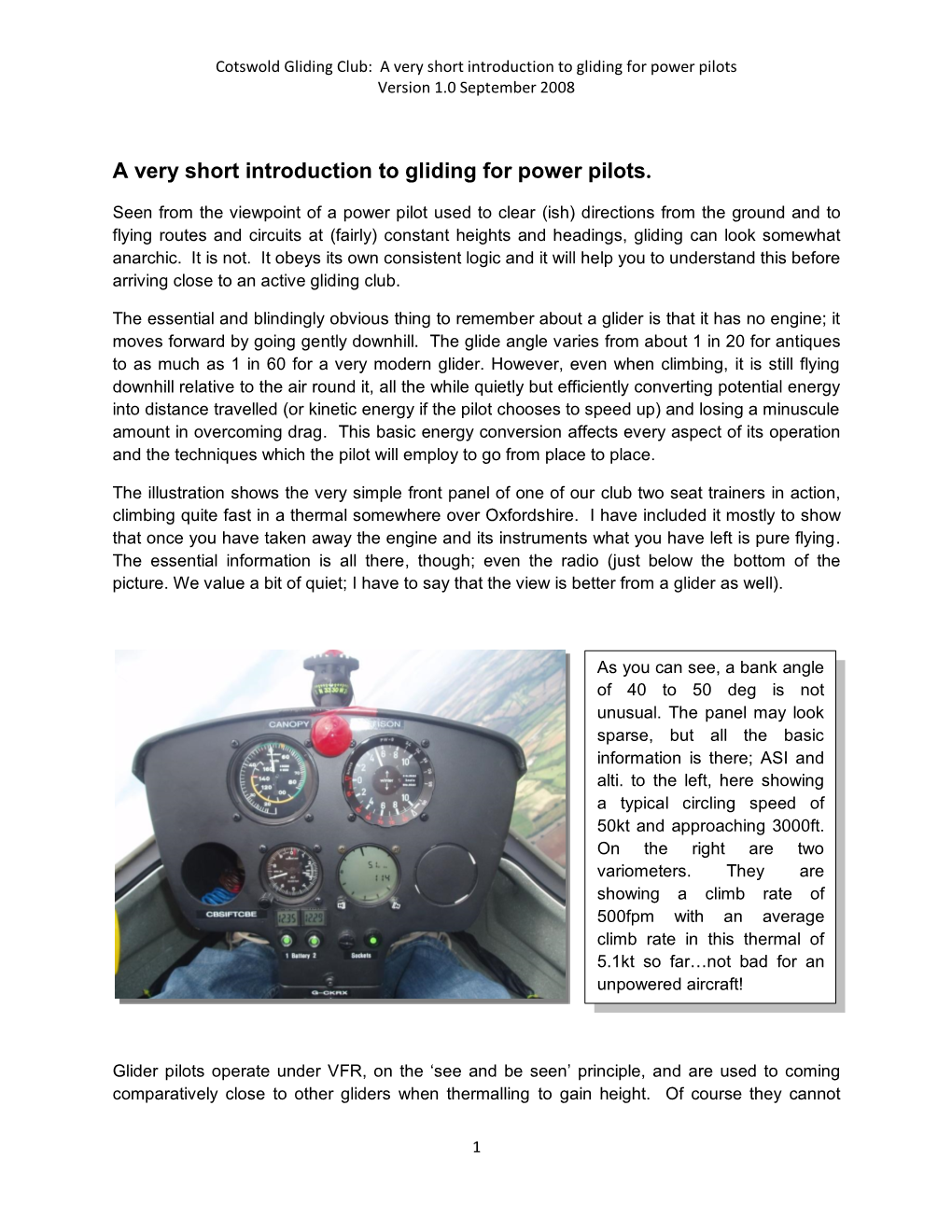

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perpetual Flight in Flow Fields

Perpetual Flight in Flow Fields by Ricardo Ayres Gomes Bencatel A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Electrical and Computer Engineering) in the University of Porto, School of Engineering Faculdade de Engenharia da Universidade do Porto 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor Fernando Lobo Pereira, Chair Professor Anouck Girard Associate Lu´ısaBastos Doctor Jos´eMorgado c Ricardo Ayres Gomes Bencatel 2012 All Rights Reserved To my family and my girlfriend, who supported my endeavors and endured the necessary absences. v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I thank with all my heart my family and my girlfriend for the support in the easy and the hard times, and for the encouragement to always do my best and surpass myself. Furthermore, I would like to thank the friendship of Nuno Costa with whom I developed and tested several model aircraft, which contributed to the knowledge required for this work. I would like to thank the support from AsasF group and the researchers from the Un- derwater Systems and Technology Laboratory, specially Jo~aoSousa and Gil Gon¸c´alves, and Pedro Almeida for their support, and in particular Jo~aoCorreia, Joel Gomes, Eduardo Oliveira, Rui Caldeira, Filipe Ferreira, Bruno Terra, Filipe Costa Ferreira, Joel Cardoso, and S´ergioFerreira for their friendship, support, and assistance. I gratefully acknowledge the support of the Portuguese Air Force Academy, specially Cap. El´oiPereira, Lt. Tiago Oliveira, Cap. Jos´eCosta, Sgt. Joaquim Gomes, Sgt. Paulo Teixeira, Lt. Gon¸caloCruz, Lt. Col. Morgado, Maj. Madruga, Lt. Jo~aoCaetano, and Sgt. Fernandes. I'm most grateful for the time I spend at the Aerospace Department from the University of Michigan. -

Space & Electronic Warfare Lexicon

1 Space & Electronic Warfare Lexicon Terms 2 Space & Electronic Warfare Lexicon Terms # - A 3 PLUS 3 - A National Missile Defense System using satellites and ground-based radars deployed close to the regions from which threats are likely. The space-based system would detect the exhaust plume from the burning rocket motor of an attacking missile. Forward-based radars and infrared-detecting satellites would resolve smaller objects to try to distinguish warheads from clutter and decoys. Based on that data, the ground-based interceptor - a hit-to-kill weapon - would fly toward an approximate intercept point, receiving course corrections along the way from the battle management system based on more up-to-date tracking data. As the interceptor neared the target its own sensors would guide it to the impact point. See also BALLISTIC MISSILE DEFENSE (BMD.) 3D-iD - A Local Positioning System (LPS) that is capable of determining the 3-D location of items (and persons) within a 3-dimensional indoor, or otherwise bounded, space. The system consists of inexpensive physical devices, called "tags" associated with people or assets to be tracked, and an infrastructure for tracking the location of each tag. NOTE: Related technology applications include EAS, EHAM, GPS, IRID, and RFID. 4GL - See FOURTH GENERATION LANGUAGE 5GL - See FIFTH GENERATION LANGUAGE A-POLE - The distance between a missile-firing platform and its target at the instant the missile becomes autonomous. Contrast with F-POLE. ABSORPTION - (RF propagation) The irreversible conversion of the energy of an electromagnetic WAVE into another form of energy as a result of its interaction with matter. -

Jet Ski for the Song of the Same Name by Bikini Kill, See Reject All American. Jet Ski Is the Brand Name of a Personal Watercraf

Jet Ski From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from Jet skiing) For the song of the same name by Bikini Kill, see Reject All American. European Personal Watercraft Championship in Crikvenica Waverunner in Japan Racing scene at the German Championship 2007 Jet Ski is the brand name of a personal watercraft manufactured by Kawasaki Heavy Industries. The name is sometimes mistakenly used by those unfamiliar with the personal watercraft industry to refer to any type of personal watercraft; however, the name is a valid trademark registered with the United States Patent and Trademark Office, and in many other countries.[1] The term "Jet Ski" (or JetSki, often shortened to "Ski"[2]) is often mis-applied to all personal watercraft with pivoting handlepoles manipulated by a standing rider; these are properly known as "stand-up PWCs." The term is often mistakenly used when referring to WaveRunners, but WaveRunner is actually the name of the Yamaha line of sit-down PWCs, whereas "Jet Ski" refers to the Kawasaki line. [3] [4] Recently, a third type has also appeared, where the driver sits in the seiza position. This type has been pioneered by Silveira Customswith their "Samba". Contents [hide] • 1 Histor y • 2 Freest yle • 3 Freeri de • 4 Close d Course Racing • 5 Safety • 6 Use in Popular Culture • 7 See also • 8 Refer ences • 9 Exter nal links [edit]History In 1929 a one-man standing unit called the "Skiboard" was developed, guided by the operator standing and shifting his weight while holding on to a rope on the front, similar to a powered surfboard.[5] While somewhat popular when it was first introduced in the late 1920s, the 1930s sent it into oblivion.[citation needed] Clayton Jacobson II is credited with inventing the personal water craft, including both the sit-down and stand-up models. -

Speaker Abstracts

Appendix E: Speaker Abstracts 100 Years of Progress in Boundary-Layer Meteorology: A look to the past, questions for the future Margaret A. LeMone NCAR (with contributions from Wayne Angevine, Fei Chen, Jimy Dudhia, Kristina Katsaros, Larry Mahrt, Jielun Sun, and Michael Tjernstrom)1 and input from Chris Fairall, Jim Fleming, Ned Patton, Shuyi Chen, and Peter Sullivan2 We define the atmospheric boundary-layer (ABL) as that layer of air directly influenced by exchange of heat and energy with the surface. Our story of the ABL begins with surface fluxes, which are dependent on surface roughness and the exchange of energy between the surface and atmosphere. The ABL is typically divided into a surface layer, through which shear production of turbulence kinetic energy is as important as buoyancy production, a well-mixed inner layer, and a transition layer that is alternately occupied by turbulent and free-atmosphere air. This division is most straightforward for a cloudless, steady-state, unstable ABL. Our history begins with the classical-physics roots from the 18th and 19th Centuries and their early applications to the atmospheric boundary layer, and the contributions from the early turbulence/boundary layer community, who developed the concept of the boundary layer and applied it to flow through wind tunnels, past aircraft wings, and sometimes in the atmosphere itself, with some reference to early discoveries from those more interested in agricultural applications. From there, we examine the boundary layer from the surface on up, through a look at our understanding of the surface energy budget, exchange coefficients and flux-profile relationships in the surface layer over land and ocean, and the study of the entire cloud-free ABL under unstable and stable conditions. -

Gliders and Model Airplanes As Tools for Japan's Mass Mobilization

DE GRUYTER DOI 10.1515/cj-2014-0001 Contemporary Japan 2014; 26(1): 1–28 Jürgen Melzer “We must learn from Germany”: gliders and model airplanes as tools for Japan’s mass mobilization Abstract: This article explores the prominent role of Germany in the emergence of Japan’s glider and model-aircraft boom. It examines how the invitation of German specialists to Japan in 1935 started a “glider fever” that enabled the Japanese military to forge close bonds with the press and an air-minded public. In the following years Nazi Germany also provided the organizational blueprint for comprehensive aviation education that mobilized all aviation activities of Japanese youth in the service of national defense. Japanese anxieties about the expansion of foreign air power thus were successfully channeled into a wave of popular enthusiasm and participation that became instrumental for Japan’s military buildup and mobilization. Keywords: German-Japanese relations, aviation education, military mobiliza- tion Jürgen Melzer: Princeton University, e-mail: [email protected] The author is a former glider pilot and airline captain. This article is largely based on research done during a one-year stay at the University of Tokyo that was generously funded by the Japan Foundation. The quote in the title is from General Inoue Ikutarō in his preface to Watanabe (1941). All translations of the cited material are the author’s. 1 Introduction By the early 1940s Japan had become a “nation of flyers.” More than ten million schoolchildren were engaged in building model airplanes and tens of thou- sands of high school students actively practiced glider flying. -

Hangar Digest Is a Publication of Th E Amc Museum Foundation Inc

THE HANGAR DIGEST IS A PUBLICATION OF TH E AMC MUSEUM FOUNDATION INC. Hangar Digest VOLUME 11, ISSUE 4 OCTOBER – DECEMBER 2011 INSIDE THIS ISSUE From the Director 3 Pvt. Benjamin, volunteer 4 Cruisin’ with the Curator 4 Museum store, V. 2.0 5 Foundation Notes 6 Silent Wings, Angry Skies 8 In and Around 10 LOOKING BACK Corey Smith, left, works to equalize the difference in air pressure in his ears following his flight aboard a Dover From almost the mo- Air Force Base Aero Club Cessna while Zachary Klinkenborg gives an enthusiastic thumbs up in reaction to his ment we opened our ride. The two were part of the AMC Museum’s annual Summer Camp, which features a week’s worth of instruc- doors back in 1986, the tion dedicated to aeronautics. A highlight of each class is a flight through the airspace around Kent County. Museum has been a field trip destination for Mother Nature Comes A-Callin’ schools and community organizations. 2011 has First a hurricane, followed by an earthquake, followed by a tropical storm. Perhaps somebody is been no exception, with trying to tell us something? the Museum playing The August 23 trembler shocked everyone. An earthquake in Delaware? I mean, earthquakes host to hundreds of only happen in California, right? youngsters. Our ever- I was at work when it hit, but instead of the teeth-rattling experience I expected because of ready corps of volunteers watching too many bad Hollywood movies, the real thing felt more like a slow motion walk across continue to do an out- a kids’ Moon Bounce. -

Preparation of Papers for AIAA Technical Conferences

Motivation for Air-Launch: Past, Present, and Future John W. Kelly,* Charles E. Rogers,† Gregory T. Brierly,‡ J. Campbell Martin,§ and Marshall G. Murphy** NASA Armstrong Flight Research Center, Edwards, California, 93523 “Air-launch” is defined as two or more air-vehicles joined and working together, that eventually separate in flight, and that have a combined performance greater than the sum of the individual parts. The use of the air-launch concept has taken many forms across civil, commercial, and military contexts throughout the history of aviation. Air-launch techniques have been applied for entertainment, movement of materiel and personnel, efficient execution of aeronautical research, increasing aircraft range, and enabling flexible and efficient launch of space vehicles. For each air-launch application identified in this paper, the motivation for that application is discussed. Nomenclature AAF = Army Air Forces AFB = Air Force base AFRC = Armstrong Flight Research Center (Edwards, California) ALT = approach and landing test ASAT = antisatellite CRV = Crew Return Vehicle D.C. = District of Columbia ESA = European Space Agency FICON = Fighter Conveyor project FRC = Flight Research Center HiMAT = Highly Maneuverable Aircraft Technology ICBM = inter-continental ballistic missile ISS = International Space Station IXV = Intermediate eXperimental Vehicle KST = Kelly Space & Technology, Inc. (San Bernadino, California) NACA = National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics NASA = National Aeronautics and Space Administration NBC = National Broadcasting Company NOTS = Naval Ordnance Test Station RAF = Royal Air Force SBIR = Small Business Innovative Research SNC = Sierra Nevada Corporation (Sparks, Nevada) TGALS = Towed-Glider Air-Launch System U.S. = United States USS = United States Ship USAF = United States Air Force VMS = Virgin Mothership VSS = Virgin Spaceship WS-199 = Weapon Systems 199 WWI = World War I * Project Manager, Exploration & Space Technology Directorate, Senior Member. -

Knowledge Organsier

The History of Flight KEY VOCABULARY: DATE WHAT HAPPENED WORDS MEANING 400 BC First kites were invented in China Aeroplane Powered flying machine with fixed wings 1485 Leonardo Da Vinci designed the ornithopter Aircraft Flying machine Aviation The world of aircraft and air travel 1783 A duck, sheep and a chicken flew in a hot air balloon. Cabin Room or space on an aircraft or ship 1903 Orville Wright achieved controlled flight for 12 seconds Cockpit Small space where the pilot(s) of an aeroplane sits Elevators Hinged areas on the horizontal stabilisers at the tail end of an aeroplane, 1910 Passenger flights began used to control the aeroplane’s angle of flight and lift on its wings 1927 Charles Lindberg flew non-stop across the Atlantic Engine Machine that provides power Flight Journey through the air 1933 Boeing 247 made its first flight with 10 passengers. Flying machine Machine that can fly through the air 1961 First flight into space Fuselage Body of an aircraft Glider Light unpowered aircraft with wings Hot air balloon o Large bag filled with hot air or gases that can carry passengers through the air in a basket Jet Aircraft with powerful jet engines The Wright Brothers Landing gear Wheels and other parts that bear the weight of an aeroplane ➢ Orville and Wilbur Wright were two brothers born in Ohio in the United States of America. Wilbur was born in 1867 and Orville was born in 1871. Modern The latest equipment or knowledge ➢ As children, the Wright brothers were given a toy helicopter by their father which worked by pulling an elastic band. -

The Pennsylvania State University the Graduate School College of Engineering

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Engineering ATMOSPHERICALLY AWARE AIRCRAFT GUIDANCE USING IN SITU OBSERVATIONS A Dissertation in Aerospace Engineering by John Bird © 2019 John Bird Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2019 The dissertation of John Bird was reviewed and approved∗ by the following: Jacob W. Langelaan Associate Professor of Aerospace Engineering Dissertation Advisor, Chair of Committee Sean Brennan Professor of Mechanical Engineering Mark Maughmer Professor of Aerospace Engineering George Young Professor of Meteorology Amy Pritchett Professor of Aerospace Engineering Head of Department of Aerospace Engineering ∗Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. ii Abstract A major challenge to widespread use of small electric UAS is their limited energy budgets and sensitivity to environmental conditions. Differences between forecast and realized weather conditions are often large enough that the energy required to complete a mission can differ significantly from that expected by a priori flight plans. This makes autonomous awareness of and response to the environmental state necessary in order to enable small UAS to conduct long-range missions. To develop this capability, the uncertain atmospheric state is decomposed into stochastic and systematic uncertainty which can be managed separately by the aircraft using speed and power output commands respectively. Speed variations enable an aircraft to preferentially spend longer in favorable areas, making the atmosphere appear more conducive to UAS flight. A speed command is developed which responds optimally to stochastic conditions while meeting a specified arrival time at a destination. A modeling system is developed which allows the aircraft to build a model of the vertical structure of the atmosphere using in situ observations and to transform the atmospheric state into a mission performance cost. -

Aircraft 1 Aircraft

Aircraft 1 Aircraft Aircraft An Airbus A380, the world's largest passenger airliner Aircraft 2 Part of a series on Categories of Aircraft Supported by Lighter-Than-Air Gases (aerostats) Unpowered Powered • Balloon • Airship Supported by LTA Gases + Aerodynamic Lift Unpowered Powered • Hybrid airship Supported by Aerodynamic Lift (aerodynes) Unpowered Powered Unpowered fixed-wing Powered fixed-wing • Glider • Powered airplane (aeroplane) • hang gliders • powered hang gliders • Paraglider • Powered paraglider • Kite • Flettner airplane • Ground-effect vehicle Powered hybrid fixed/rotary wing • Tiltwing • Tiltrotor • Mono Tiltrotor • Mono-tilt-rotor rotary-ring • Coleopter Unpowered Powered rotary-wing rotary-wing • Rotor kite • Autogyro • Gyrodyne ("Heliplane") • Helicopter Powered aircraft driven by flapping • Ornithopter Other Means of Lift Unpowered Powered • Hovercraft • Flying Bedstead • Avrocar Aircraft 3 An aircraft is a vehicle which is able to fly by being supported by the air, or in general, the atmosphere of a planet. An aircraft counters the force of gravity by using either static lift or by using the dynamic lift of an airfoil, or in a few cases the downward thrust from jet engines.[1] Although rockets and missiles also travel through the atmosphere, most are not considered aircraft because they use rocket thrust instead of aerodynamics as the primary means of lift. However, rocket planes and cruise missiles are considered aircraft because they rely on lift from the air. The human activity which surrounds aircraft is called aviation. Manned aircraft are flown by an onboard pilot. Unmanned aerial vehicles may be remotely controlled or self-controlled by onboard computers. Target drones are an example of UAVs. Aircraft may be classified by different criteria, such as lift type, propulsion, usage and others. -

Unsteady Aerodynamic and Dynamic Analysis of the Meridian UAS in A

Unsteady Aerodynamic and Dynamic Analysis of the Meridian UAS in a Rolling-Yawing Motion By Ryan Lykins Submitted to the graduate degree program in Aerospace Engineering and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science. ________________________________ Chairperson, Dr. Shawn S. Keshmiri ________________________________ Dr. C. Edward Lan ________________________________ Dr. Richard Hale Date Defended: November 27th, 2013 The Thesis Committee for Ryan Lykins certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Unsteady Aerodynamic and Dynamic Analysis of the Meridian UAS in a Rolling-Yawing Motion ________________________________ Chairperson, Dr. Shawn S. Keshmiri Date approved: November 27th, 2013 ii Abstract The nonlinear and unsteady aerodynamic effects of operating the Meridian unmanned aerial system (UAS) in crosswinds and at high angular rates is investigated in this work. The Meridian UAS is a large autonomous aircraft, with a V-tail configuration, operated in Polar Regions for the purpose of remotely measuring ice sheet thickness. The inherent nonlinear coupling produced by the V-tail, along with the strong atmospheric disturbances, has made classical model identification methods inadequate for proper model development. As such, a powerful tool known as Fuzzy Logic Modeling (FLM) was implemented to generate time- dependent, nonlinear, and unsteady aerodynamic models using flight test data collected in Greenland in 2011. Prior to performing FLM, compatibility analysis is performed on the data, for the purpose of systematic bias removal and airflow angle estimation. As one of the advantages of FLM is the ability to model unsteady aerodynamics, the reduced frequency for both longitudinal and lateral- directional motions is determined from the unbiased data, using Theodorsen’s theory of unsteadiness, which serves as an input parameter in modeling. -

Albatross-Like Utilization of Wind Gradient for Unpowered Flight of Fixed-Wing Aircraft

applied sciences Article Albatross-Like Utilization of Wind Gradient for Unpowered Flight of Fixed-Wing Aircraft Shangqiu Shan * ID , Zhongxi Hou and Bingjie Zhu College of Aerospace Sciences and Engineering, National University of Defense Technology, Changsha 410073, China; [email protected] (Z.H.); [email protected] (B.Z.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-137-8729-3515 Received: 3 September 2017; Accepted: 12 October 2017; Published: 14 October 2017 Abstract: The endurance of an aircraft can be considerably extended by its exploitation of the hidden energy of a wind gradient, as an albatross does. The process is referred to as dynamic soaring and there are two methods for its implementation, namely, sustainable climbing and the Rayleigh cycle. In this study, the criterion for sustainable climbing was determined, and a bio-inspired method for implementing the Rayleigh cycle in a shear wind was developed. The determined sustainable climbing criterion promises to facilitate the development of an unpowered aircraft and the choice of a more appropriate soaring environment, as was demonstrated in this study. The criterion consists of three factors, namely, the environment, aerodynamics, and wing loading. We develop an intuitive explanation of the Raleigh cycle and analyze the energy mechanics of utilizing a wind gradient in unpowered flight. The energy harvest boundary and extreme power point were determined and used to design a simple bio-inspired guidance strategy for implementing the Rayleigh cycle. The proposed strategy, which involves the tuning of a single parameter, can be easily implemented in real-time applications. In the results and discussions, the effects of each factor on climbing performance are examined and the sensitivity of the aircraft factor is discussed using five examples.