Report of the Air Issues Task Force on Small Airport Viability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Netletter #1379 | November 29, 2017

NetLetter #1379 | November 29, 2017 Vickers Viscount CF-THS Dear Reader, Welcome to the NetLetter, an Aviation based newsletter for Air Canada, TCA, CP Air, Canadian Airlines and all other Canadian based airlines that once graced the Canadian skies. The NetLetter is published on the second and fourth weekend of each month. If you are interested in Canadian Aviation History, and vintage aviation photos, especially as it relates to Trans-Canada Air Lines, Air Canada, Canadian Airlines International and their constituent airlines, then we're sure you'll enjoy this newsletter. Our website is located at www.thenetletter.net Please click the links below to visit our NetLetter Archives and for more info about the NetLetter. Women in Aviation Valentina Tereshkova, the Soviet cosmonaut, became the first woman in space in 1963. More info at Wikipedia. Air Canada News Controllers ignore Mayday calls. Canadian officials say they’ll talk to their counterparts in India after air traffic controllers reportedly ignored a series of Mayday calls from an Air Canada Boeing 787 and ordered the crew to enter holds instead. The Dreamliner had finished a 16-hour flight from Toronto to Mumbai on Sept. 18 but a runway overrun by a SpiceJet Boeing 737 closed the active runway. Rather than going to its alternate, the aircraft was put in a series of holds by Mumbai controllers. After an hour of turning left, the Air Canada plane was getting low on fuel so the crew asked for clearance to its alternate. They were told the unidentified alternate airport was unavailable because it was at capacity and unable to take any more traffic. -

IATA CLEARING HOUSE PAGE 1 of 21 2021-09-08 14:22 EST Member List Report

IATA CLEARING HOUSE PAGE 1 OF 21 2021-09-08 14:22 EST Member List Report AGREEMENT : Standard PERIOD: P01 September 2021 MEMBER CODE MEMBER NAME ZONE STATUS CATEGORY XB-B72 "INTERAVIA" LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY B Live Associate Member FV-195 "ROSSIYA AIRLINES" JSC D Live IATA Airline 2I-681 21 AIR LLC C Live ACH XD-A39 617436 BC LTD DBA FREIGHTLINK EXPRESS C Live ACH 4O-837 ABC AEROLINEAS S.A. DE C.V. B Suspended Non-IATA Airline M3-549 ABSA - AEROLINHAS BRASILEIRAS S.A. C Live ACH XB-B11 ACCELYA AMERICA B Live Associate Member XB-B81 ACCELYA FRANCE S.A.S D Live Associate Member XB-B05 ACCELYA MIDDLE EAST FZE B Live Associate Member XB-B40 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS AMERICAS INC B Live Associate Member XB-B52 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS INDIA LTD. D Live Associate Member XB-B28 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS UK LIMITED A Live Associate Member XB-B70 ACCELYA UK LIMITED A Live Associate Member XB-B86 ACCELYA WORLD, S.L.U D Live Associate Member 9B-450 ACCESRAIL AND PARTNER RAILWAYS D Live Associate Member XB-280 ACCOUNTING CENTRE OF CHINA AVIATION B Live Associate Member XB-M30 ACNA D Live Associate Member XB-B31 ADB SAFEGATE AIRPORT SYSTEMS UK LTD. A Live Associate Member JP-165 ADRIA AIRWAYS D.O.O. D Suspended Non-IATA Airline A3-390 AEGEAN AIRLINES S.A. D Live IATA Airline KH-687 AEKO KULA LLC C Live ACH EI-053 AER LINGUS LIMITED B Live IATA Airline XB-B74 AERCAP HOLDINGS NV B Live Associate Member 7T-144 AERO EXPRESS DEL ECUADOR - TRANS AM B Live Non-IATA Airline XB-B13 AERO INDUSTRIAL SALES COMPANY B Live Associate Member P5-845 AERO REPUBLICA S.A. -

Unsolved Rapes Raise Safety Fears

Cats missing Get tested 'Bali begins A number of cats have Local residents are urged to get More than 40 youth from Terrace, mysteriously disappeared from the their blood tested for the hepatitis Smithers and Kitimat turned out Horseshoe area\NEWS A3 C virus\COMMUNITY B1 for a fastball clinic\SPORTS B6 WEDNESDAY $1.00 PLUS 7¢ GST (S1.10 plus 8¢ GST outside of the April 12, 2000 Terrace area) T . NDARD VOL. 13 NO. 1 Unsolved rapes raise safety fears By CHRISTIANA WIENS of Kalum Street, happened around 8 RCMP say her attackers are be- Udsen said regional investigators not normally hear about." TERRACE RCMP are question- a.m., Wednesday, March 22. tween 18 and 23 years old. One of the based in Prince Rupert, in town last Of particular concern, she said, is ing a number of suspects after two The suspect - believed to be a na- men is believed to be native, while Tuesday to help Terrace's drug section the March 31 attack on Davis Street. the other's ethnicity isn't known. execute two warrants, were tied up "Two (attackers) is not a random extremely violent sexual attacks tive male wearing a blue bandana to mask his face - is described as having Udsen said the attacks do not ap- and unable to help this case. act," she said. "They have to discuss on women in the past three weeks. a thin to medium build. pear to be related to earlier stalking Meanwhile, he said, local women and they have to debrief." But as of Apr. -

G410020002/A N/A Client Ref

Solicitation No. - N° de l'invitation Amd. No. - N° de la modif. Buyer ID - Id de l'acheteur G410020002/A N/A Client Ref. No. - N° de réf. du client File No. - N° du dossier CCC No./N° CCC - FMS No./N° VME G410020002 G410020002 RETURN BIDS TO: Title – Sujet: RETOURNER LES SOUMISSIONS À: PURCHASE OF AIR CARRIER FLIGHT MOVEMENT DATA AND AIR COMPANY PROFILE DATA Bids are to be submitted electronically Solicitation No. – N° de l’invitation Date by e-mail to the following addresses: G410020002 July 8, 2019 Client Reference No. – N° référence du client Attn : [email protected] GETS Reference No. – N° de reference de SEAG Bids will not be accepted by any File No. – N° de dossier CCC No. / N° CCC - FMS No. / N° VME other methods of delivery. G410020002 N/A Time Zone REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL Sollicitation Closes – L’invitation prend fin Fuseau horaire DEMANDE DE PROPOSITION at – à 02 :00 PM Eastern Standard on – le August 19, 2019 Time EST F.O.B. - F.A.B. Proposal To: Plant-Usine: Destination: Other-Autre: Canadian Transportation Agency Address Inquiries to : - Adresser toutes questions à: Email: We hereby offer to sell to Her Majesty the Queen in right [email protected] of Canada, in accordance with the terms and conditions set out herein, referred to herein or attached hereto, the Telephone No. –de téléphone : FAX No. – N° de FAX goods, services, and construction listed herein and on any Destination – of Goods, Services, and Construction: attached sheets at the price(s) set out thereof. -

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

For Immediate Release Bearskin Airlines Increases Service

August 31, 2016 For Immediate Release Bearskin Airlines Increases Service Between Thunder Bay, Sault Ste Marie and Sudbury Bearskin Airlines today announced increased frequency of service between Thunder Bay, Sault Ste Marie and Sudbury effective September 19, 2016. One additional eastbound morning flight and one additional westbound evening flight will be offered each weekday, complimenting existing service between Northern Ontario’s largest cities. A second nonstop evening flight between Thunder Bay and Sudbury will also be offered on Fridays only. All nonstop service between Thunder Bay-Sault Ste Marie and Sault Ste Marie-Sudbury will increase from 23 to 33 flights weekly. Service between Thunder Bay-Sudbury will increase from 29 flights to 40 flights weekly including a combination of nonstop and one stop same aircraft service. Only Bearskin Airlines offers nonstop and one stop same aircraft service between Northern Ontario’s three largest cities, saving up to 8 hours or more on round trip travel as compared to connecting via Toronto. These new early morning and evening flights are designed to provide the longest workday possible for eastbound business travellers while minimizing the travel time required. No other airline offers faster more efficient service between Northern Ontario’s largest cities. In addition to the most direct service available, fares have been reduced as much as 60% since 2014 and only Bearskin Airlines permits your first checked bag to travel free, providing for savings up to $35 each way. Bearskin also provides the most efficient linkages between NW and NE Ontario via its Thunder Bay Airport hub. Bearskin Airlines is Northern Ontario’s hometown airline and currently offers up to 100 scheduled flights daily to 12 destinations from Winnipeg in the west to North Bay in the east. -

BUILDING the FUTURE KELOWNA Aboriginal Training and Mentoring Farmers’ Delights

In-flight Magazine for Pacific Coastal Airlines BOOMING Vancouver Island construction on the rise TASTY BUILDING THE FUTURE KELOWNA Aboriginal training and mentoring Farmers’ delights June /July 2014 | Volume 8 | Number 3 NEW PRICE ED HANDJA Personal Real Estate Corporation & SHELLEY MCKAY Your BC Oceanfront Team Specializing in Unique Coastal Real Estate in British Columbia Ed 250.287.0011 • Shelley 250.830.4435 Toll Free 800.563.7322 [email protected] [email protected] Great Choices for Recreational Use & Year-round Living • www.bcoceanfront.com • Great Choices for Recreational Use & Year-round Living • www.bcoceanfront.com Use & Year-round • Great Choices for Recreational Living • www.bcoceanfront.com Use & Year-round Great Choices for Recreational West Coast Vancouver Island: Three 10 acre Kyuquot Sound, Walters Cove: Premier shing Sonora Island Oceanfront: This one has it all - oceanfront properties next to the Broken Island and outdoor recreation from this west coast 3 acre property with 400ft low-bank oceanfront, Marine Group. 275ft – 555ft of low bank beach Vancouver Island community. Government dock good, protected moorage, 4 dwellings, gardens, a front. There are roughed in internal access trails and general store, power and water. beautiful setting and wonderful views. Sheltered and a shared rock jetty for of oading. Water 1100sqft classic home, new private moorage location, southern exposure, water licenses access only properties. Region renowned for $224,900 for domestic water and power generation. An shing, whale watching and boating. Great value. Older homestead, private moorage $184,900 ideal remote residence or lodge in the popular $83,600 - $103,400 1000sqft 2bdrm home, plus full basement $199,000 Discovery Islands. -

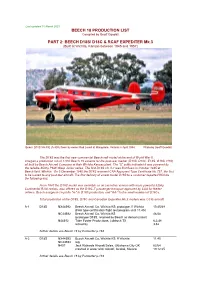

BEECH D18S/ D18C & RCAF EXPEDITER Mk.3 (Built at Wichita, Kansas Between 1945 and 1957)

Last updated 10 March 2021 BEECH 18 PRODUCTION LIST Compiled by Geoff Goodall PART 2: BEECH D18S/ D18C & RCAF EXPEDITER Mk.3 (Built at Wichita, Kansas between 1945 and 1957) Beech D18S VH-FIE (A-808) flown by owner Rod Lovell at Mangalore, Victoria in April 1984. Photo by Geoff Goodall The D18S was the first new commercial Beechcraft model at the end of World War II. It began a production run of 1,800 Beech 18 variants for the post-war market (D18S, D18C, E18S, G18S, H18), all built by Beech Aircraft Company at their Wichita Kansas plant. The “S” suffix indicated it was powered by the reliable 450hp P&W Wasp Junior series. The first D18S c/n A-1 was first flown in October 1945 at Beech field, Wichita. On 5 December 1945 the D18S received CAA Approved Type Certificate No.757, the first to be issued to any post-war aircraft. The first delivery of a new model D18S to a customer departed Wichita the following day. From 1947 the D18C model was available as an executive version with more powerful 525hp Continental R-9A radials, also offered as the D18C-T passenger transport approved by CAA for feeder airlines. Beech assigned c/n prefix "A-" to D18S production, and "AA-" to the small number of D18Cs. Total production of the D18S, D18C and Canadian Expediter Mk.3 models was 1,035 aircraft. A-1 D18S NX44592 Beech Aircraft Co, Wichita KS: prototype, ff Wichita 10.45/48 (FAA type certification flight test program until 11.45) NC44592 Beech Aircraft Co, Wichita KS 46/48 (prototype D18S, retained by Beech as demonstrator) N44592 Tobe Foster Productions, Lubbock TX 6.2.48 retired by 3.52 further details see Beech 18 by Parmerter p.184 A-2 D18S NX44593 Beech Aircraft Co, Wichita KS: ff Wichita 11.45 NC44593 reg. -

Southern Labrador Regional Airport Pre-Design Studyopens in New Window

Southern Labrador Regional Airport Pre-Design Study Port Hope Simpson, Labrador Prepared for: Department of Works, Services and Transportation EDM Project # 20340 Proposed 1220 m x 30 m Runway Proposed 915 m x 23 m Runway March 8, 2005 March 8, 2005 GOVERNMENT OF NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR Southern Labrador Regional Airport March 2005 Pre-Design Study Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1.0 General 1.1 Background ..................................................................................1 1.2 Terms of Reference.......................................................................1 1.3 Regional Airport Definition ..........................................................1 1.4 Existing Port Hope Simpson Aerodrome.......................................2 2.0 Review of Southern Labrador’s Airport Operations 2.1 Aerodromes ..................................................................................6 2.2 Needs Assessment ........................................................................7 2.3 Proposed Facilities/Infrastructure..................................................9 3.0 Evaluation of Existing Port Hope Simpson Aerodrome/Site 3.1 Summary of Evaluation ..............................................................11 3.2 Conclusion..................................................................................12 4.0 Engineering Work Completed to Date 4.1 General.......................................................................................15 4.2 Design Criteria............................................................................15 -

Management Discussion and Analysis of Results of Operations and Financial Condition

2016 MANAGEMENT DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS OF RESULTS OF OPERATIONS AND FINANCIAL CONDITION February 17, 2017 2016 Management’s Discussion and Analysis of Results of Operations and Financial Condition TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Highlights ................................................................................................... 1 2. Introduction and Key Assumptions ............................................................. 3 3. About Air Canada ........................................................................................ 5 4. Strategy ..................................................................................................... 7 5. Overview ...................................................................................................17 6. Results of Operations – Full Year 2016 versus Full Year 2015 ....................19 7. Results of Operations – Fourth Quarter 2016 vs Fourth Quarter 2015 ........29 8. Fleet ..........................................................................................................40 9. Financial and Capital Management .............................................................43 9.1. Liquidity .................................................................................................43 9.2. Financial Position ...................................................................................43 9.3. Adjusted Net Debt ..................................................................................44 9.4. Working Capital ......................................................................................45 -

Exchange Industrial Income Fund Since Its Units Began Trading on the Toronto Venture Exchange on May 6, 2004

EEXXCCHHAANNGGEE IINNDDUUSSTTRRIIAALL IINNCCOOMMEE FFUUNNDD 2004 Annual Report TABLE OF CONTENTS LETTER FROM THE CHAIRMAN................................................................................................1 CORPORATE PROFILE ..............................................................................................................4 THE FUND’S ACQUISITION STRATEGY ...................................................................................5 PERIMETER AVIATION LTD.......................................................................................................7 KEEWATIN AIR LIMITED ACQUISITION ANNOUNCED APRIL 2005.......................................7 MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS .....................................................................8 MANAGEMENT’S RESPONSIBILITY FOR FINANCIAL REPORTING ....................................15 AUDITORS’ REPORT ................................................................................................................16 AUDITED CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS.........................................................17 NOTES TO CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENT ........................................................23 UNITHOLDER INFORMATION ..................................................................................................33 LETTER FROM THE CHAIRMAN To Exchange Unitholders: On behalf of the Trustees and management, I am pleased to report on the accomplishments of Exchange Industrial Income Fund since its units began trading on the Toronto -

Netletter #1454 | January 23, 2021 Trans-Canada Air Lines 60Th

NetLetter #1454 | January 23, 2021 Trans-Canada Air Lines 60th Anniversary Plaque - Fin 264 Dear Reader, Welcome to the NetLetter, an Aviation based newsletter for Air Canada, TCA, CP Air, Canadian Airlines and all other Canadian based airlines that once graced the Canadian skies. The NetLetter is published on the second and fourth weekend of each month. If you are interested in Canadian Aviation History, and vintage aviation photos, especially as it relates to Trans-Canada Air Lines, Air Canada, Canadian Airlines International and their constituent airlines, then we're sure you'll enjoy this newsletter. Please note: We do our best to identify and credit the original source of all content presented. However, should you recognize your material and are not credited; please advise us so that we can correct our oversight. Our website is located at www.thenetletter.net Please click the links below to visit our NetLetter Archives and for more info about the NetLetter. Note: to unsubscribe or change your email address please scroll to the bottom of this email. NetLetter News We have added 333 new subscribers in 2020 and 9 new subscribers so far in 2021. We wish to thank everyone for your support of our efforts. We always welcome feedback about Air Canada (including Jazz and Rouge) from our subscribers who wish to share current events, memories and photographs. Particularly if you have stories to share from one of the legacy airlines: Canadian Airlines, CP Air, Pacific Western, Eastern Provincial, Wardair, Nordair, Transair, Air BC, Time Air, Quebecair, Calm Air, NWT Air, Air Alliance, Air Nova, Air Ontario, Air Georgian, First Air/Canadian North and all other Canadian based airlines that once graced the Canadian skies.