The Selection M D Condition of Clothing of Low

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Sailor of King George by Frederick Hoffman

The Project Gutenberg EBook of A Sailor of King George by Frederick Hoffman This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: A Sailor of King George Author: Frederick Hoffman Release Date: December 13, 2008 [Ebook 27520] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A SAILOR OF KING GEORGE*** [I] A SAILOR OF KING GEORGE THE JOURNALS OF CAPTAIN FREDERICK HOFFMAN, R.N. 1793–1814 EDITED BY A. BECKFORD BEVAN AND H.B. WOLRYCHE-WHITMORE v WITH ILLUSTRATIONS LONDON JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET 1901 [II] BRADBURY, AGNEW, & CO. LD., PRINTERS, LONDON AND TONBRIDGE. [III] PREFACE. In a memorial presented in 1835 to the Lords of the Admiralty, the author of the journals which form this volume details his various services. He joined the Navy in October, 1793, his first ship being H.M.S. Blonde. He was present at the siege of Martinique in 1794, and returned to England the same year in H.M.S. Hannibal with despatches and the colours of Martinique. For a few months the ship was attached to the Channel Fleet, and then suddenly, in 1795, was ordered to the West Indies again. Here he remained until 1802, during which period he was twice attacked by yellow fever. The author was engaged in upwards of eighteen boat actions, in one of which, at Tiberoon Bay, St. -

Dance Changes Everything - Junior Show

Show Information Packet for Dance Changes Everything - Junior Show Saturday, June 15, 2013 at 3:00 p.m. at the Bankhead Theater, Livermore Performance is about 2 hours long with a 15 min. intermission PLEASE READ THIS PACKET VERY CAREFULLY AND KEEP IT FOR FUTURE REFERENCE. The following classes are in this show: Monday 3:30 Intermediate TKL/Jazz/Musical Theater Tuesday 10:00 Creative Combo Tuesday 4:45 Beginning Jazz Wednesday 10:00 Creative Combo Wednesday 2:45 Intro to Jazz (both 2:45 classes) Wednesday 3:30 Intro Hip Hop Friday 4:30 Beginning/Intermediate Hip Hop Saturday 10:00 Creative Combo Saturday 11:00 Tumbling Saturday 1:30 Tumbling Ashling, Believe, In Motion, Jazz Explosion, Musical Theater and Elite Jazz Companies Dads Dance Crew Blocking and Dress Rehearsal at Bankhead Theater: Friday, June 14th @ 1:30 – 5:00pm (please note time change) We will do blocking and dress rehearsal together from 1:30-5:00pm. Please send your dancer to the theater in their costume with hair and make-up ready. We will be practicing our dances and getting familiar with the theater as well as getting used to dancing away from the studio mirrors. The bow practice will help you practice going out on stage and getting to know your order of your final bows for the show. I will do my best to stay on schedule. 1:30-3:00 Jazz Company & Student Choreography only (no costumes necessary) 3:00-5:05- Blocking and dress rehearsal The dancers who are dancing from 3:00-5:05 need to come in costume. -

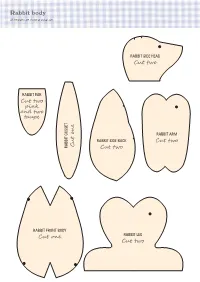

Rabbit Body All Templates Are Shown at Actual Size

Rabbit body All templates are shown at actual size. RABBIT SIDE HEAD Cut two RABBIT EAR Cut two pink and two taupe RABBIT ARM RABBIT SIDE BACK Cut two Cut one RABBIT GUSSET Cut two RABBIT FRONT BODY RABBIT LEG Cut one Cut two Schoolboy’s uniform: trousers, blazer, sweater, collar and tie All templates are shown at actual size. SCHOOL BLAZER BACK Cut one BLAZER FRONT Cut two SCHOOL BLAZER SLEEVE Cut two SCHOOL BLAZER COLLAR Cut one SHIRT COLLAR Cut one BLAZER POCKET Cut two SCHOOL TROUSERS Cut two SCHOOL TIE Cut one SCHOOL V-NECK SWEATER Cut one Schoolgirl’s uniform: dress and cardigan All templates are shown at actual size. SCHOOL DRESS CUFF SCHOOL DRESS SLEEVE Cut two Cut two SCHOOL DRESS COLLAR Cut one SCHOOL DRESS BACK SCHOOL DRESS FRONT Cut one Cut two SCHOOL DRESS SKIRT Cut one on fold Cut one SCHOOL DRESS TIE BELT FOLD SCHOOL CARDIGAN Cut one Squirrel body All templates are shown at actual size. SQUIRREL EAR Cut four SQUIRREL HEAD Cut two Cut one SQUIRREL HEAD GUSSET SQUIRREL FRONT BODY Cut one SQUIRREL BACK BODY Cut two SQUIRREL LEG Cut two SQUIRREL TAIL Cut one SQUIRREL ARM Cut two Summer clothes: sailor dress and collar All templates are shown at actual size. SAILOR DRESS SLEEVE Cut two SAILOR DRESS BACK BODICE Cut two SAILOR COLLAR SAILOR DRESS FRONT BODICE Cut one Cut one SAILOR DRESS SKIRT FOLD Cut one on fold SAILOR DRESS COLLAR Cut one on bias Gardening clothes: dungarees and scarf All templates are shown at actual size. -

Lower School Uniform Policy the School Strongly Encourages Students to Label All Appropriate Uniform Items to Aid the School in Returning Lost Items

Lower School Uniform Policy The School strongly encourages students to label all appropriate uniform items to aid the School in returning lost items. Beginner, Pre-Kindergarten, and Kindergarten Students • Dress: Navy Sailor dress with white tie • Shorts: Modesty shorts may be worn under dresses • Pants: Navy Bermuda-length shorts or trousers with elastic waistband • Shirt: White polo style shirt (without logo) • Shoes: Solid white or black Velcro tennis shoes • Socks: Plain or ESD logo white or navy socks. Sock must completely cover the ankle bone at all times (ankle socks are not permitted). • Headwear: Red, white or navy blue bows or headbands only. Scarves are not permitted. • Jewelry: Jewelry is limited to non-dangling earrings and a watch. • Nail Polish: Nail polish is not permitted. • Hair: Hair is to be neat, clean, properly combed, and should not obscure a student’s face. Primer through Fourth Grade Students • Skirts: Navy pleated skirt. Skirts should be no shorter than three inches above the knee. • Shirt: Middy blouse with red tie, white oxford shirt or polo style shirt (without logo) • Shorts: Navy blue ESD logo shorts should be worn under skirts for PE. • Pants: Navy Bermuda-length shorts or trousers • Belts: Black or brown narrow belt, or Vineyard Vines ESD Crest Belt. Must be worn with pants or shorts. • Shoes: Navy and white saddle shoes, navy and white Keds, solid black leather loafers or low, solid black athletic shoes. Slip on athletic shoes are not permitted. Third and fourth grade students need athletic shoes for PE. • Socks: Plain or ESD logo white or navy socks. -

Kimagure Orange Road TV Series Disc 4 Liner Notes (PDF)

KIMAGURE ORANGE ROAD DISC 4, EPISODES 13 – 16 Episode 13 – Everybody is Looking! Hikaru’s Super Transformation. (06/29/87) “Hikaru's made a debut, in Jr. High! Maybe I should try it too!” This is in reference to the myriad of top idol stars of the 80's who became overnight sensations. They were often labeled as “average junior/senior high school students” without much exceptional talents but were made celebrities because of their looks or personalities. “Wanna drink?” Viewers might note how most beverage cans in anime are so skinny. In Japan, this size (250 ml or approximately 8 oz) is standard. “Does she think it's okay to come to school wearing those clothes?!” Most junior and senior high schools in Japan have strict dress codes. The uniforms such as those in KOR are the most traditional ones: boys are outfitted with fairly tight-fitting, dark (usually black, sometimes navy) suits, while girls wear the so-called “seiraa-fuku” (“sailor dress”). Some schools also require hats to be worn, others might require boys to shave their heads or girls to keep their hair within a certain length. Note that the “furyoo” (“delinquent”) students are typically seen wearing oversized or unbuttoned uniforms --- e.g., guys with 50's greased hairdo wearing sunglasses and pants several sizes too big are most likely furyoo or a member of some gang! To address dress code and other related issues that were frowned upon by most students, many magnet schools that popped up during the 80's offered such alternatives as uniforms designed by top fashion moguls. -

Norell-Brochure.Pdf

Seventh Avenue at 27th Street, New York City NORELL: DEAN OF AMERICAN FASHION February 9–April 14, 2018 Hours: Tuesday–Friday, noon–8 pm Saturday, 10 am–5 pm Closed Sunday, Monday, and legal holidays Admission is free. #Norell #MuseumatFIT fitnyc.edu/norell Norell: Dean of American Fashion has been made possible thanks to the generosity of the Couture Council of The Museum at FIT. Cover: Photograph by Milton H. Greene © 2017 Joshua Greene, archiveimages.com. DEAN OF Interior, right-hand panel: Photograph by Milton H. Greene © 2017 Joshua Greene, archiveimages.com. Back: Photograph of Kenneth Pool Collection © Marc Fowler. AMERICAN FASHION February 9–April 14, 2018 Norman Norell (1900-1972) one of the greatest fashion designers of the mid-twentieth century, is best remembered for redefining sleek, sophisticated, American glamour. This retrospective exhibition presents approximately 100 garments, accessories, and related material chosen by designer Jeffery Banks. Many of the objects come from the private collection of designer Kenneth Pool. They are a testament to the breadth of Norell’s creativity and his enduring impact on fashion. This array of suits, jersey separates, menswear-inspired outerwear, and Norell’s hallmark sequined “mermaid” dresses reflects the profound respect these contemporary designers have for Norell and his oeuvre. Born Norman David Levinson in Noblesville, Indiana, the designer adopted the more soigné moniker of Norman Above left: Norell, evening ensemble with striped duchesse satin ball skirt trimmed in black fox, Above left: Norell, belted dresses with mini capes in pink linen and black wool, 1964. fall 1967. Above center: Norell, Prince of Wales tweed reefer coat, late 1960s. -

Press Release

Office of Communications and External Relations telephone 212 217.4700 fax 212 217.4701 email: [email protected] November 27, 2017 Cheri Fein Executive Director of Public and Media Relations 212 217.4700; [email protected] Norell: Dean of American Fashion February 9–April 14, 2018 The Museum at FIT The Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology (MFIT) presents Norell: Dean of American Fashion (February 9–April 14, 2018), a retrospective exhibition of work by pioneering designer Norman Norell, who created some of the finest and most innovative clothing ever crafted in the United States. On view in Norell will be approximately 100 ensembles and accessories from MFIT’s permanent collection, as well as a compelling selection of objects borrowed from the stellar private collection of Kenneth Pool. The exhibition is organized by Patricia Mears, MFIT deputy director, and designer Jeffery Banks, guest curator. The exhibition emphasizes key Norell designs that were developed early on and remained constant throughout his career. Many examples of his day and evening wear are on view. These garments, accessories, and related objects are organized thematically to illustrate the range of Norell’s extraordinary output and the consistently outstanding quality of work produced by his atelier. Although some of the objects date back to the early 1930s, most were designed during the last 12 years of Norell’s career—from 1960 to 1972. This phase is notable because Norell bought out his investors in the 1960s, and from then on, his name alone appeared on his label. It also was arguably his most Photograph by Milton H. -

The Queer Fashionability of the Sailor Uniform in Inter-War France and Britain

‘Our jolly marin wear’: the queer fashionability of the sailor uniform in inter-war France and Britain. Andrew Stephenson, University of East London In September 1927 the English painter Edward Burra wrote to his close friend, the photographer Barbara Ker-Seymer in London from Cassis in the South of France about his holiday adventures on the Riviera. As well as time spent sunbathing and watching the hustle and bustle of the Mediterranean crowds, he related stories of drinking in seedy harbour-side bars and cafés and told tales of dancing in lively bal-musettes (dance halls). Burra recorded that they had also escaped the sleepy pace of Cassis for the livelier, larger port of Marseilles. The main entertainment in Marseilles consisted of watching the antics of the sailors on leave in the French Navy’s major Mediterranean base and naval dockyard. With a keen eye for the latest fashion trends, Burra updated her about the current styles on display on the Riviera and he conveyed his pleasure at buying sailor wear from the small shops in the Old Town by the port in Marseilles that specialised in selling French marin (navy) uniforms and its various accoutrements. Close to the Marseilles portside, in the Quartier réservé/ red light area of narrow Medieval streets and dark courtyards with open fronted brothels, Burra was fascinated by the prostitutes who plied their trade to the matelots (sailors) writing that ‘the Grand Rue where we get our jolly marin wear and linen trousers the guide book says is a veritable ghetto of houses of ill fame my dear I stares into every window hoping for a thrill’ (Chappell 1985: 36-37). -

A Comparison of Child-Care Manuals, Fashion Journals and Mail-Order Catalogues on the Subject of Children's Dress 1875-1900

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1989 Prescription and Practice: A Comparison of Child-Care Manuals, Fashion Journals and Mail-Order Catalogues on the Subject of Children's Dress 1875-1900 Christina Jean Bates College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Fashion Design Commons Recommended Citation Bates, Christina Jean, "Prescription and Practice: A Comparison of Child-Care Manuals, Fashion Journals and Mail-Order Catalogues on the Subject of Children's Dress 1875-1900" (1989). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625490. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-9ym7-ay60 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PRESCRIPTION AND PRACTICE: A COMPARISON OF CHILD-CARE MANUALS, FASHION JOURNALS AND MAIL-ORDER CATALOGUES ON THE SUBJECT OF CHILDREN'S DRESS 1875 - 1900 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of American Studies The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Christina Bates 1989 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Christina Bates Approved, July 1989 rv*. ( Barbara Carson UaJL Bruce McConachie —* Linda Baumgarten Colonial Williamsburg Youndation TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS..................................... -

Fustians in Englishmen's Dress: from Cloth to Emblem

SYKAS: FUSTIANS IN ENGLISHMEN’S DRESS Fustians in Englishmen’s Dress: from Cloth to Emblem By PHILIP A. SYKAS This paper examines the nature of the textiles known as fustians, originally imported but later manufactured in England. The focus is on eighteenth-century England when fustians underwent further development into modern cloth types. Evidence of the use of fustians for men’s dress, and the status of those who wore them, is explored to shed further light on the developments leading up to the association of fustian with working- class men. The paper is based on a presentation delivered at the Costume Society Symposium: Town and Country Style in 2007. The association of fustians with rural men was familiar enough in the mid-nineteenth century to feature in a village festival sketched in the children’s classic, Tom Brown’s Schooldays. From the churchyard, the field is seen ‘thronged with country folk; the men in clean, white smocks or velveteen or fustian coats’.1 The book was based on the author’s own experiences at Rugby school from 1834 to 1842, and makes use of clothing to mark class difference and social status in the countryside. During the same years, the labouring men of England’s towns also claimed fustians as their own. So much so, that the Chartist leader Feargus O’Connor (1796?-1855) proclaimed‘fu stian jackets, blistered hands, and unshorn chins’ as the proud emblems of the urban working man.2 When did fustian become such a part of the labouring scene across both urban and rural settings? This paper examines the use of fustians in the previous century to shed light on the evolution of associations between fustian and men’s dress. -

Lower School Dress Code

Lower School Dress Code Dress Code Realizing that a relationship exists between standards of dress and behavior/performance and that high standards of dress foster a positive self-image, Lake Highland Preparatory School maintains certain expectations which result in the following guidelines of student dress. Students are expected to dress and to groom themselves in a way which reflects neatness, moderation and appropriateness for school. Lake Highland Preparatory School students are also expected to adhere to the spirit of the guidelines specified below which reflect conservative standards of acceptability. Parental assistance in assuring that the guidelines are followed is expected and very much appreciated. All uniform items must be purchased from the school uniform company. Clothing items in The Source are not necessarily within LHP Dress Code, but may be permitted on Spirit Days. Sweaters, sweatshirts, jackets, and coats for indoor use must be purchased from the school uniform company or from the school store. Following are also some additional guidelines for the required dress code. Shirts: Shirts must be tucked in at all times so the belt or waistband is visible. Shirts may not be tucked in and then “bloused” over. At least the first button of knit shirts must be fastened. Only plain white undershirts may be worn underneath shirts. Shirts may not be layered. Shorts, Skirts, Slacks: Shorts and skirts must be modest in length, no shorter than 4 inches above the knee and no longer than the middle of the knee. Short skirts and shorts do not reflect the values of LHPS. Shorts and slacks must be worn properly at the waist, not riding low on the hips. -

Redland Christian Academy

Redland Christian Academy Student Handbook R.C.A. “Falcon” Redland Christian Academy has served the South Dade Community for over 40 years, offering quality education in a Christian environment. As you read this handbook, we pray that you will support the Christian principles set forth and experience the truth contained in the scripture: “Train up a child in the way he should go and when he is old he will not depart from it” (Proverbs 22:6). 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Christian Philosophy of Education………… Page 4 Mission Statement………….………………. Page 4 General Information……….…………. …… Page 5 School Programs…………………………..., Page 6 School Policies and Procedures…........ …….Page 9 Classroom Policies……………….…… …… Page 15 Standards of Conduct…….……..…….…… Page 20 Dress Code…………………….…………… Page 27 Academic Standards for Graduation… …….Page 32 Conclusion………………………….… …….Page 33 2 3 CHRISTIAN PHILOSOPHY OF EDUCATION “The fear of the Lord is the beginning of knowledge and wisdom.” Proverbs 1:7 Christian Education must begin with the realization that God is the source of all truth. He is in all and for all. He is our frame of reference as we learn from the world around us. Therefore, His Word holds a position of priority over our philosophy of education. The Christian philosophy of education is the teaching of facts that are based on the truth and the Lord Jesus Christ and that we do all for the glory of God. Its purpose is to convince the student of the need for a personal relationship with Jesus Christ. Its goal is to nurture, admonish and encourage the student to live a life of service, fully dedicated to and dependent on God in every area of their lives (Ephesians 4:1-6).