Mapos Buang Dictionary Page 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clothing of Kansas Women, 1854-1870

CLOTHING OF KANSAS WOMEN 1854 - 1870 by BARBARA M. FARGO B. A., Washburn University, 1956 A MASTER'S THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF SCIENCE Department of Clothing, Textiles and Interior Design KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 1969 )ved by Major Professor ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author wishes to express sincere appreciation to her adviser, Dr. Jessie A. Warden, for her assistance and guidance during the writing of this thesis. Grateful acknowledgment also is expressed to Dr. Dorothy Harrison and Mrs. Helen Brockman, members of the thesis committee. The author is indebted to the staff of the Kansas State Historical Society for their assistance. TABLE OP CONTENTS PAGE ACKNOWLEDGMENT ii INTRODUCTION AND PROCEDURE 1 REVIEW OF LITERATURE 3 CLOTHING OF KANSAS WOMEN 1854 - 1870 12 Wardrobe planning 17 Fabric used and produced in the pioneer homes 18 Style and fashion 21 Full petticoats 22 Bonnets 25 Innovations in acquisition of clothing 31 Laundry procedures 35 Overcoming obstacles to fashion 40 Fashions from 1856 44 Clothing for special occasions 59 Bridal clothes 66 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS 72 REFERENCES 74 LIST OF PLATES PLATE PAGE 1. Bloomer dress 15 2. Pioneer woman and child's dress 24 3. Slat bonnet 30 4. Interior of a sod house 33 5. Children's clothing 37 6. A fashionable dress of 1858 42 7. Typical dress of the 1860's 47 8. Black silk dress 50 9. Cape and bonnet worn during the 1860's 53 10. Shawls 55 11. Interior of a home of the late 1860's 58 12. -

A Sailor of King George by Frederick Hoffman

The Project Gutenberg EBook of A Sailor of King George by Frederick Hoffman This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: A Sailor of King George Author: Frederick Hoffman Release Date: December 13, 2008 [Ebook 27520] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A SAILOR OF KING GEORGE*** [I] A SAILOR OF KING GEORGE THE JOURNALS OF CAPTAIN FREDERICK HOFFMAN, R.N. 1793–1814 EDITED BY A. BECKFORD BEVAN AND H.B. WOLRYCHE-WHITMORE v WITH ILLUSTRATIONS LONDON JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET 1901 [II] BRADBURY, AGNEW, & CO. LD., PRINTERS, LONDON AND TONBRIDGE. [III] PREFACE. In a memorial presented in 1835 to the Lords of the Admiralty, the author of the journals which form this volume details his various services. He joined the Navy in October, 1793, his first ship being H.M.S. Blonde. He was present at the siege of Martinique in 1794, and returned to England the same year in H.M.S. Hannibal with despatches and the colours of Martinique. For a few months the ship was attached to the Channel Fleet, and then suddenly, in 1795, was ordered to the West Indies again. Here he remained until 1802, during which period he was twice attacked by yellow fever. The author was engaged in upwards of eighteen boat actions, in one of which, at Tiberoon Bay, St. -

Dress Code Is a Presentation of Who We Are.” 1997-98 Grand Officers

CLOTHING GUIDELINES: MEMBERS AND ADULTS (Reviewed annually during Grand Officer Leadership; changes made as needed) Changes made by Jr. Grand Executive Committee (November 2016) “A dress code is a presentation of who we are.” 1997-98 Grand Officers One of the benefits of Rainbow is helping our members mature into beautiful, responsible young women - prepared to meet challenges with dignity, grace and poise. The following guidelines are intended to help our members make appropriate clothing choices, based on the activities they will participate in as Rainbow girls. The Clothing Guidelines will be reviewed annually by the Jr. Members of the Grand Executive Committee. Recommendations for revisions should be forwarded to the Supreme Officer prior to July 15th of each year. REGULAR MEETINGS Appropriate: Short dress, including tea-length and high-low length, or skirt and blouse or sweater or Nevada Rainbow polo shirt (tucked in) with khaki skirt or denim skirt. Vests are acceptable. Skirt length: Ideally, HEMS should not be more than three inches above the knee. Skirts, like pencil skirts that hug the body and require “adjustment” after bowing or sitting, are unacceptable. How to tell if a skirt has a Rainbow appropriate length? Try the “Length Test”, which includes: When bowing from the waist, are your undergarments visible, or do you need to hold your skirt - or shirt - down in the back? If so, it's too short for a Rainbow meeting. Ask your mother or father to stand behind you and in front of you while you bow from the waist. If she/he gasps, the outfit is not appropriate for a Rainbow meeting. -

Abstract of Counting Systems of Papua New Guinea and Oceania

Abstract of http://www.uog.ac.pg/glec/thesis/ch1web/ABSTRACT.htm Abstract of Counting Systems of Papua New Guinea and Oceania by Glendon A. Lean In modern technological societies we take the existence of numbers and the act of counting for granted: they occur in most everyday activities. They are regarded as being sufficiently important to warrant their occupying a substantial part of the primary school curriculum. Most of us, however, would find it difficult to answer with any authority several basic questions about number and counting. For example, how and when did numbers arise in human cultures: are they relatively recent inventions or are they an ancient feature of language? Is counting an important part of all cultures or only of some? Do all cultures count in essentially the same ways? In English, for example, we use what is known as a base 10 counting system and this is true of other European languages. Indeed our view of counting and number tends to be very much a Eurocentric one and yet the large majority the languages spoken in the world - about 4500 - are not European in nature but are the languages of the indigenous peoples of the Pacific, Africa, and the Americas. If we take these into account we obtain a quite different picture of counting systems from that of the Eurocentric view. This study, which attempts to answer these questions, is the culmination of more than twenty years on the counting systems of the indigenous and largely unwritten languages of the Pacific region and it involved extensive fieldwork as well as the consultation of published and rare unpublished sources. -

SWART, RENSKA L." 12/06/2016 Matches 149

Collection Contains text "SWART, RENSKA L." 12/06/2016 Matches 149 Catalog / Objectid / Objname Title/Description Date Status Home Location O 0063.001.0001.008 PLAIN TALK TICKET 1892 OK MCHS Building Ticket Ticket to a Y.M.C.A. program entitled "Plain Talk, No. 5" with Dr. William M. Welch on the subject of "The Prevention of Contagion." The program was held Thursday, October 27, 1892 at the Central Branch of the YMCA at 15th and Chestnut Street in what appears to be Philadelphia O 0063.001.0002.012 1931 OK MCHS Building Guard, Lingerie Safety pin with chain and snap. On Original marketing card with printed description and instructions. Used to hold up lingerie shoulder straps. Maker: Kantslip Manufacturing Co., Pittsburgh, PA copyright date 1931 O 0063.001.0002.013 OK MCHS Building Case, Eyeglass Brown leather case for eyeglasses. Stamped or pressed trim design. Material has imitation "cracked-leather" pattern. Snap closure, sewn construction. Name inside flap: L. F. Cronmiller 1760 S. Winter St. Salem, OR O 0063.001.0002.018 OK MCHS Building Massager, Scalp Red Rubber disc with knob-shaped handle in center of one side and numerous "teeth" on other side. Label molded into knob side. "Fitch shampoo dissolves dandruff, Fitch brush stimulates circulation 50 cents Massage Brush." 2 1/8" H x 3 1/2" dia. Maker Fitch's. place and date unmarked Page 1 Catalog / Objectid / Objname Title/Description Date Status Home Location O 0063.001.0002.034 OK MCHS Building Purse, Change Folding leather coin purse with push-tab latch. Brown leather with raised pattern. -

On Halloween

^ *r. i f ■ K f ■y IM lSDAY, OCTOBER W, 1#M PAO* TWENTY-FOUR xttptting Ifpralb \ Your Public Health Nurse Needs Your Support-Give to Drive Now A Halloween costume party for A b o u t T o w n Junior members of Covenant Con-1 Average Daily Net Preas Run The WeotlMt gregational (jhiirrh will be h e l^ o - For the Week Emled For •« 0. ff, WeMMr i The Army-Navy AuxlUaiy wlU morrow at 7 p.m. gt the homoBof MANCHESTER Oet. U . 19M « 0UTSTANDIN8 QUALITY, Miss Eltls Johnson, 31 Oak Grove OPEN TOMIHT elect offlcera after g meatless Fair smt eaa| agata lamgibK LaW' potluck Wednesday, Nov. 4, at BL y n Sk-Si. MaaOy M r, UtOa ckaat* W 6:80 p.m. at the clubhouse. UBLIC MARKE TILL till 13,036 Memorial Temple, Pythian Bis ► ' 1 803 805 MAIM STREhT temperatara Salanlay. IB ters, will hold a kitchen social at. Member ef the Andit Mo. priced for thrift Anderaon-Bhea Auxiliary, VFW, ihe home-'of Mrs. Herbert Alley, BoreM e f OlrealmthMi will hold a card party tomorrow 66 Washington 8t„ tomorrow at HrirteheeUr— A City of Village Charm at 6 p.m. at the pest home. 8 p.m. Membera arc asked to bring articles. Friends are Invited. (ClaaMflad ABverlMag ea Faga 1 6 ) PRICE FIVE CEfm There’s plenty of evidence that you fgrt Members n{ Washington Loyal VOL. LXXIX, NO. 26 (EIGHTEEN PAGES) MANCHESTER. CONN.. FRIDAY. OCTOBER SO. 1969 Orange Lodge will meet at Orange f R M U i n C N H X ilfi more srood eating for your money, when Hall Bnnday at 9:30 a.m., and. -

![AMBAKICH [Aew]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0790/ambakich-aew-690790.webp)

AMBAKICH [Aew]

Endangered languages listing: AMBAKICH [aew] Number of speakers: 770; Total population of language area: 1,964 (2003). Ambakich (also called Aion or Porapora) is a language spoken in the Angoram district of East Sepik Province, Papua New Guinea. Ambakich is classified as one of the “Grass” languages (Laycock 1973); these languages are now regarded as members of the “Lower Sepik-Ramu” family (Foley 2005). Ambakich speakers mostly live in villages along the Porapora River, which flows northward into the Sepik River. One village (Yaut) is located on the Keram River, southwest of the other villages. Speakers call their language “Ambakich”, whereas “Aion” is the name of the ethnic group. The population in 2003 was probably greater than the 1,964 reported. The language has SOV structure. An SIL survey in 2003 (Potter et al, forthcoming) found that Ambakich has very low vitality. While most adults were able to speak Ambakich, both children and youth spoke and understood Tok Pisin far better than Ambakich. Ambakich speakers report positive attitudes toward their language, stating they value it as an important part of their culture. However, parents use more Tok Pisin than Ambakich when speaking to their children. Communities verbally support the use of Ambakich in schools and teacher attitudes are positive; however teachers feel that the children are not learning the language because it is not being used in the home. Tok Pisin is used in all domains, including home, cultural, religious, social, legal, trade and other interactions with outsiders. Ambakich speakers are close neighbours to the Taiap language studied by Kulick (1992). -

4. Old Track, Old Path

4 Old track, old path ‘His sacred house and the place where he lived,’ wrote Armando Pinto Correa, an administrator of Portuguese Timor, when he visited Suai and met its ruler, ‘had the name Behali to indicate the origin of his family who were the royal house of Uai Hali [Wehali] in Dutch Timor’ (Correa 1934: 45). Through writing and display, the ruler of Suai remembered, declared and celebrated Wehali1 as his origin. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the Portuguese increased taxes on the Timorese, which triggered violent conflict with local rulers, including those of Suai. The conflict forced many people from Suai to seek asylum across the border in West Timor. At the end of 1911, it was recorded that more than 2,000 East Timorese, including women and children, were granted asylum by the Dutch authorities and directed to settle around the southern coastal plain of West Timor, in the land of Wehali (La Lau 1912; Ormelling 1957: 184; Francillon 1967: 53). On their arrival in Wehali, displaced people from the village of Suai (and Camenaça) took the action of their ruler further by naming their new settlement in West Timor Suai to remember their place of origin. Suai was once a quiet hamlet in the village of Kletek on the southern coast of West Timor. In 1999, hamlet residents hosted their brothers and sisters from the village of Suai Loro in East Timor, and many have stayed. With a growing population, the hamlet has now become a village with its own chief asserting Suai Loro origin; his descendants were displaced in 1911. -

![Mission: New Guinea]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4485/mission-new-guinea-804485.webp)

Mission: New Guinea]

1 Bibliography 1. L. [Letter]. Annalen van onze lieve vrouw van het heilig hart. 1896; 14: 139-140. Note: [mission: New Guinea]. 2. L., M. [Letter]. Annalen van onze lieve vrouw van het heilig hart. 1891; 9: 139, 142. Note: [mission: Inawi]. 3. L., M. [Letter]. Annalen van onze lieve vrouw van het heilig hart. 1891; 9: 203. Note: [mission: Inawi]. 4. L., M. [Letter]. Annalen van onze lieve vrouw van het heilig hart. 1891; 9: 345, 348, 359-363. Note: [mission: Inawi]. 5. La Fontaine, Jean. Descent in New Guinea: An Africanist View. In: Goody, Jack, Editor. The Character of Kinship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1973: 35-51. Note: [from lit: Kuma, Bena Bena, Chimbu, Siane, Daribi]. 6. Laade, Wolfgang. Der Jahresablauf auf den Inseln der Torrestraße. Anthropos. 1971; 66: 936-938. Note: [fw: Saibai, Dauan, Boigu]. 7. Laade, Wolfgang. Ethnographic Notes on the Murray Islanders, Torres Strait. Zeitschrift für Ethnologie. 1969; 94: 33-46. Note: [fw 1963-1965 (2 1/2 mos): Mer]. 8. Laade, Wolfgang. Examples of the Language of Saibai Island, Torres Straits. Anthropos. 1970; 65: 271-277. Note: [fw 1963-1965: Saibai]. 9. Laade, Wolfgang. Further Material on Kuiam, Legendary Hero of Mabuiag, Torres Strait Islands. Ethnos. 1969; 34: 70-96. Note: [fw: Mabuiag]. 10. Laade, Wolfgang. The Islands of Torres Strait. Bulletin of the International Committee on Urgent Anthropological and Ethnological Research. 1966; 8: 111-114. Note: [fw 1963-1965: Saibai, Dauan, Boigu]. 11. Laade, Wolfgang. Namen und Gebrauch einiger Seemuscheln und -schnecken auf den Murray Islands. Tribus. 1969; 18: 111-123. Note: [fw: Murray Is]. -

Aspects of Tok Pisin Grammar

PACIFIC LINGUISTICS Senie� B - No. 66 ASPECTS OF TOK PIS IN GRAMMAR by Ellen B. Woolford Department of Linguistics Research School of Pacific Studies THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Woodford, E.B. Aspects of Tok Pisin grammar. B-66, vi + 123 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1979. DOI:10.15144/PL-B66.cover ©1979 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PACIFIC LINGUIS TICS is issued through the Lingui�tie Ci�ete 06 Canbe��a and consists of four series: SERIES A - OCCASIONAL PAPERS SERIES B - MONOGRAPHS SERIES C - BOOKS SERIES V - SPECIAL PUBLICATIONS EDITOR: S.A. Wurrn. ASSOCIATE EDITORS: D.C. Laycock, C.L. Voorhoeve, D.T. Tryon, T.E. Dutton. EDITORIAL ADVISERS: B. Bender, University of Hawaii J. Lynch, University of Papua D. Bradley, University of Melbourne New Guinea A. Capell, University of Sydney K.A. McElhanon, University of Texas S. Elbert, University of Hawaii H. McKaughan, university of Hawaii K. Franklin, Summer Institute of P. MUhlh�usler, Linacre College, Linguistics oxford W.W. Glover, Summer Institute of G.N. O'Grady, University of Linguistics victoria, B.C. G. Grace, University of Hawaii A.K. pawley, University of Hawaii M.A.K. Halliday, university of K. Pike, Univeraity of Michigan; Sydney Summer Institute of Linguistics A. Healey, Summer Institute of E.C. Pol orne, University of Texas Linguistics G. Sankoff, Universite de Montreal L. Hercus, Australian National E. Uhlenbeck, University of Leiden University J.W.M. Verhaar, University of N.D. -

Dance Changes Everything - Junior Show

Show Information Packet for Dance Changes Everything - Junior Show Saturday, June 15, 2013 at 3:00 p.m. at the Bankhead Theater, Livermore Performance is about 2 hours long with a 15 min. intermission PLEASE READ THIS PACKET VERY CAREFULLY AND KEEP IT FOR FUTURE REFERENCE. The following classes are in this show: Monday 3:30 Intermediate TKL/Jazz/Musical Theater Tuesday 10:00 Creative Combo Tuesday 4:45 Beginning Jazz Wednesday 10:00 Creative Combo Wednesday 2:45 Intro to Jazz (both 2:45 classes) Wednesday 3:30 Intro Hip Hop Friday 4:30 Beginning/Intermediate Hip Hop Saturday 10:00 Creative Combo Saturday 11:00 Tumbling Saturday 1:30 Tumbling Ashling, Believe, In Motion, Jazz Explosion, Musical Theater and Elite Jazz Companies Dads Dance Crew Blocking and Dress Rehearsal at Bankhead Theater: Friday, June 14th @ 1:30 – 5:00pm (please note time change) We will do blocking and dress rehearsal together from 1:30-5:00pm. Please send your dancer to the theater in their costume with hair and make-up ready. We will be practicing our dances and getting familiar with the theater as well as getting used to dancing away from the studio mirrors. The bow practice will help you practice going out on stage and getting to know your order of your final bows for the show. I will do my best to stay on schedule. 1:30-3:00 Jazz Company & Student Choreography only (no costumes necessary) 3:00-5:05- Blocking and dress rehearsal The dancers who are dancing from 3:00-5:05 need to come in costume. -

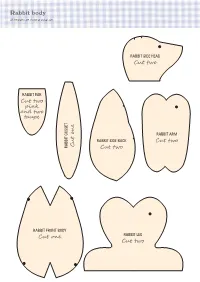

Rabbit Body All Templates Are Shown at Actual Size

Rabbit body All templates are shown at actual size. RABBIT SIDE HEAD Cut two RABBIT EAR Cut two pink and two taupe RABBIT ARM RABBIT SIDE BACK Cut two Cut one RABBIT GUSSET Cut two RABBIT FRONT BODY RABBIT LEG Cut one Cut two Schoolboy’s uniform: trousers, blazer, sweater, collar and tie All templates are shown at actual size. SCHOOL BLAZER BACK Cut one BLAZER FRONT Cut two SCHOOL BLAZER SLEEVE Cut two SCHOOL BLAZER COLLAR Cut one SHIRT COLLAR Cut one BLAZER POCKET Cut two SCHOOL TROUSERS Cut two SCHOOL TIE Cut one SCHOOL V-NECK SWEATER Cut one Schoolgirl’s uniform: dress and cardigan All templates are shown at actual size. SCHOOL DRESS CUFF SCHOOL DRESS SLEEVE Cut two Cut two SCHOOL DRESS COLLAR Cut one SCHOOL DRESS BACK SCHOOL DRESS FRONT Cut one Cut two SCHOOL DRESS SKIRT Cut one on fold Cut one SCHOOL DRESS TIE BELT FOLD SCHOOL CARDIGAN Cut one Squirrel body All templates are shown at actual size. SQUIRREL EAR Cut four SQUIRREL HEAD Cut two Cut one SQUIRREL HEAD GUSSET SQUIRREL FRONT BODY Cut one SQUIRREL BACK BODY Cut two SQUIRREL LEG Cut two SQUIRREL TAIL Cut one SQUIRREL ARM Cut two Summer clothes: sailor dress and collar All templates are shown at actual size. SAILOR DRESS SLEEVE Cut two SAILOR DRESS BACK BODICE Cut two SAILOR COLLAR SAILOR DRESS FRONT BODICE Cut one Cut one SAILOR DRESS SKIRT FOLD Cut one on fold SAILOR DRESS COLLAR Cut one on bias Gardening clothes: dungarees and scarf All templates are shown at actual size.