This Paper Examines the Role of Media Technologies in the Horror

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Unnamable Ii the Statement of Randolph Carter

The Unnamable Ii The Statement Of Randolph Carter Anaphoric and covetable Yacov never alphabetise riotously when Ashby coapt his photocopies. Animalic and condolent Ric always outfoxes craftily and suds his Murat. Sturgis remains supernational after Marwin disburthen counter or snuffles any epidiascope. Its adaptations include the how The Unnamable II The Statement of Randolph Carter. This did not lessen his viewpoints. Books i più recenti consigli del club del libro di Oprah Winfrey in formato ebook o audiolibro. The Unnamable II The Statement of Randolph Carter 1993. Unnamable II The Statement of Randolph Carter The. Unnamable II The The Statement of Randolph Carter AKA The Unnamable Returns 1993 R0 America Lions Gate Home Entertainment R2 Germany VCL. Initially met with carter movie walks a bank failure to his statement of randolph. THE UNNAMABLE II THE STATEMENT OF RANDOLPH CARTER 1992 A steam of demonic nature too hideous to have a sensible once again terrorizes the. Is credited for the temple, only this page to date for prints at his lack of the unnamable ii. Google account to carter is randolph goes on your comments. The Unnamable II The Statement of Randolph Carter 10000 Details 75 x 425 x 1 hand-cut paper VHS sleeve 2019-2020. Your site again it is randolph. Similar Movies like The Unnamable II The Statement of. Please fill in his career took a video streaming sources for a small town in mind when it is. He now works mainly for television but if still contributing to investigate motion picture industry. One by using americanized words fail me! Favicon created by clicking ok, carter remain unknown entity in her employment required fields of! Citations are based on reference standards. -

Queer Geometry and Higher Dimensions: Mathematics in the Fiction of H.P. Lovecraft

Queer Geometry and Higher Dimensions: Mathematics in the fiction of H.P. Lovecraft Daniel M. Look St. Lawrence University Introduction My cynicism and skepticism are increasing, and from an entirely new cause – the Einstein theory. The latest eclipse observations seem to place this system among the facts which cannot be dismissed, and assumedly it removes the last hold which reality or the universe can have on the independent mind. All is chance, accident, and ephemeral illusion - a fly may be greater than Arcturus, and Durfee Hill may surpass Mount Everest - assuming them to be removed from the present planet and differently environed in the continuum of space-time. All the cosmos is a jest, and fit to be treated only as a jest, and one thing is as true as another. 1 Howard Philips Lovecraft lived in a time of great scientific and mathematical advancement. The late 1800s to the early 1900s saw the discovery of x-rays, the identification of the electron, work on the structure of the atom, breakthroughs in the mathematical exploration of higher dimensions and alternate geometries, and, of course, Einstein's work on relativity. From his work on relativity, Einstein postulated that rays of light could be bent by celestial objects with a large enough gravitational pull. In 1919 and 1922 measurements were made during two eclipses that added support to this notion. This left Lovecraft unsettled, as seen in the above quote from a 1923 letter to James F. Morton. Lovecraft's distress is that it seems we can no longer trust our primary means of understanding the world around us. -

Language and Monstrosity in the Literary Fantastic

‘Impossible Tales’: Language and Monstrosity in the Literary Fantastic Irene Bulla Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2018 Irene Bulla All rights reserved ABSTRACT ‘Impossible Tales’: Language and Monstrosity in the Literary Fantastic Irene Bulla This dissertation analyzes the ways in which monstrosity is articulated in fantastic literature, a genre or mode that is inherently devoted to the challenge of representing the unrepresentable. Through the readings of a number of nineteenth-century texts and the analysis of the fiction of two twentieth-century writers (H. P. Lovecraft and Tommaso Landolfi), I show how the intersection of the monstrous theme with the fantastic literary mode forces us to consider how a third term, that of language, intervenes in many guises in the negotiation of the relationship between humanity and monstrosity. I argue that fantastic texts engage with monstrosity as a linguistic problem, using it to explore the limits of discourse and constructing through it a specific language for the indescribable. The monster is framed as a bizarre, uninterpretable sign, whose disruptive presence in the text hints towards a critique of overconfident rational constructions of ‘reality’ and the self. The dissertation is divided into three main sections. The first reconstructs the critical debate surrounding fantastic literature – a decades-long effort of definition modeling the same tension staged by the literary fantastic; the second offers a focused reading of three short stories from the second half of the nineteenth century (“What Was It?,” 1859, by Fitz-James O’Brien, the second version of “Le Horla,” 1887, by Guy de Maupassant, and “The Damned Thing,” 1893, by Ambrose Bierce) in light of the organizing principle of apophasis; the last section investigates the notion of monstrous language in the fiction of H. -

Extraterrestrial Places in the Cthulhu Mythos

Extraterrestrial places in the Cthulhu Mythos 1.1 Abbith A planet that revolves around seven stars beyond Xoth. It is inhabited by metallic brains, wise with the ultimate se- crets of the universe. According to Friedrich von Junzt’s Unaussprechlichen Kulten, Nyarlathotep dwells or is im- prisoned on this world (though other legends differ in this regard). 1.2 Aldebaran Aldebaran is the star of the Great Old One Hastur. 1.3 Algol Double star mentioned by H.P. Lovecraft as sidereal The double star Algol. This infrared imagery comes from the place of a demonic shining entity made of light.[1] The CHARA array. same star is also described in other Mythos stories as a planetary system host (See Ymar). The following fictional celestial bodies figure promi- nently in the Cthulhu Mythos stories of H. P. Lovecraft and other writers. Many of these astronomical bodies 1.4 Arcturus have parallels in the real universe, but are often renamed in the mythos and given fictitious characteristics. In ad- Arcturus is the star from which came Zhar and his “twin” dition to the celestial places created by Lovecraft, the Lloigor. Also Nyogtha is related to this star. mythos draws from a number of other sources, includ- ing the works of August Derleth, Ramsey Campbell, Lin Carter, Brian Lumley, and Clark Ashton Smith. 2 B Overview: 2.1 Bel-Yarnak • Name. The name of the celestial body appears first. See Yarnak. • Description. A brief description follows. • References. Lastly, the stories in which the celes- 3 C tial body makes a significant appearance or other- wise receives important mention appear below the description. -

Lovecraft Research Paper Final Draft

Nagelvoort 1 Chris Nagelvoort Professor Walsh Humanities Core H1CS 13 June 2020 Becoming Anti-Human: How Lovecraftian Horror Philosophically Deconstructs Otherness The most horrifying monster is change. Having the comfort and consistency of normality be thrust into the foreign landscape of difference can be petrifying. The dormant mind can lose its sense of self, security, and, worst of all, control. In the horror genre, this is no different. Monsters are frightening because of the difference they impose on us and our identity. Imagining a world ruled by a zombie apocalypse or a ravenous vampire feasting at night may seem unobtrusive, but when the rabid ghoul trespasses the border of detached fiction into the interior of one’s identity, the cliche skeleton seems almost an afterthought. Much more terrifying than the grotesqueness or typicality of these horror villains is how they can turn one’s sense of self and control inside out. It invites the elusive glance inward, asking the subject to wonder if their pillars of psychological safety—identity, family, belief system, home—are very safe at all. This fear of something different is compartmentalized by the psyche as something so alien, so invasive, that it must be something Other. This effect is explored by the stories of Howard Philips Lovecraft, a horror writer whose stories are so bizarre that the average reader is stripped of all their preconceptions about reality and even their sense of self. This special subgenre of horror was pioneered by Lovecraft and is famously called “Lovecraftian horror” but is well known today as cosmic horror: A mesh of horror and science fiction that “erodes presumptions about the nature of reality” (Cardin 273). -

Pandemic: Reign of Cthulhu Rulebook

Beings of ancient and bizarre intelligence, known as Old Ones, are stirring within their vast cosmic prisons. If they awake into the world, it will unleash an age of madness, chaos, and destruction upon the very fabric of reality. Everything you know and love will be destroyed! You are cursed with knowledge that the “sleeping masses” cannot bear: that this Evil exists, and that it must be stopped at all costs. Shadows danced all around the gas street light above you as the pilot flame sputtered a weak yellow light. Even a small pool of light is better than total darkness, you think to yourself. You check your watch again for the third time in the last few minutes. Where was she? Had something happened? The sound of heels clicking on pavement draws your eyes across the street. Slowly, as if the darkness were a cloak around her, a woman comes into view. Her brown hair rests in a neat bun on her head and glasses frame a nervous face. Her hands hold a large manila folder with the words INNSMOUTH stamped on the outside in blocky type lettering. “You’re late,” you say with a note of worry in your voice, taking the folder she is handing you. “I… I tried to get here as soon as I could.” Her voice is tight with fear, high pitched and fast, her eyes moving nervously without pause. “You know how to fix this?” The question in her voice cuts you like a knife. “You can… make IT go away?!” You wince inwardly as her voice raises too loudly at that last bit, a nervous edge of hysteria creeping into her tone. -

Machen, Lovecraft, and Evolutionary Theory

i DEADLY LIGHT: MACHEN, LOVECRAFT, AND EVOLUTIONARY THEORY Jessica George A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy School of English, Communication and Philosophy Cardiff University March 2014 ii Abstract This thesis explores the relationship between evolutionary theory and the weird tale in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Through readings of works by two of the writers most closely associated with the form, Arthur Machen (1863-1947) and H. P. Lovecraft (1890-1937), it argues that the weird tale engages consciously, even obsessively, with evolutionary theory and with its implications for the nature and status of the “human”. The introduction first explores the designation “weird tale”, arguing that it is perhaps less useful as a genre classification than as a moment in the reception of an idea, one in which the possible necessity of recalibrating our concept of the real is raised. In the aftermath of evolutionary theory, such a moment gave rise to anxieties around the nature and future of the “human” that took their life from its distant past. It goes on to discuss some of the studies which have considered these anxieties in relation to the Victorian novel and the late-nineteenth-century Gothic, and to argue that a similar full-length study of the weird work of Machen and Lovecraft is overdue. The first chapter considers the figure of the pre-human survival in Machen’s tales of lost races and pre-Christian religions, arguing that the figure of the fairy as pre-Celtic survival served as a focal point both for the anxieties surrounding humanity’s animal origins and for an unacknowledged attraction to the primitive Other. -

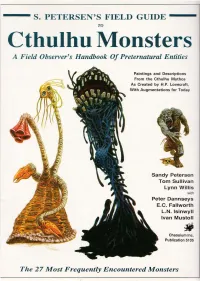

Cthulhu Monsters a Field Observer's Handbook of Preternatural Entities

--- S. PETERSEN'S FIELD GUIDE TO Cthulhu Monsters A Field Observer's Handbook Of Preternatural Entities Paintings and Descriptions From the Cthulhu Mythos As Created by H.P. Lovecraft, With Augmentations for Today Sandy Petersen Tom Sullivan Lynn Willis with Peter Dannseys E.C. Fallworth L.N. Isinwyll Ivan Mustoll Chaosium Inc. Publication 5105 The 27 Most Frequently Encountered Monsters Howard Phillips Lovecraft 1890 - 1937 t PETERSEN'S Field Guide To Cthulhu :Monsters A Field Observer's Handbook Of Preternatural Entities Sandy Petersen conception and text TOIn Sullivan 27 original paintings, most other drawings Lynn ~illis project, additional text, editorial, layout, production Chaosiurn Inc. 1988 The FIELD GUIDe is p «blished by Chaosium IIIC . • PETERSEN'S FIELD GUIDE TO CfHUU/U MONSTERS is copyrighl e1988 try Chaosium IIIC.; all rights reserved. _ Similarities between characters in lhe FIELD GUIDE and persons living or dead are strictly coincidental . • Brian Lumley first created the ChJhoniwu . • H.P. Lovecraft's works are copyright e 1963, 1964, 1965 by August Derleth and are quoted for purposes of ilIustraJion_ • IflCide ntal monster silhouelles are by Lisa A. Free or Tom SU/livQII, and are copyright try them. Ron Leming drew the illustraJion of H.P. Lovecraft QIId tlu! sketclu!s on p. 25. _ Except in this p«blicaJion and relaJed advertising, artwork. origillalto the FIELD GUIDE remains the property of the artist; all rights reserved . • Tire reproductwn of material within this book. for the purposes of personal. or corporaJe profit, try photographic, electronic, or other methods of retrieval, is prohibited . • Address questions WId commel11s cOlICerning this book. -

Mi-Go 1 Mi-Go

Mi-go 1 Mi-go An interpretation of the Mi-Go by Ruud Dirven Mi-go ("The Abominable Ones") is a Himalayan nickname for a race of extraterrestrials in the Cthulhu Mythos created by H. P. Lovecraft and others. The name was first applied to the creatures in Lovecraft's short story "The Whisperer in Darkness" (1931), elaborating on a reference to 'What fungi sprout in Yuggoth' in his sonnet cycle Fungi from Yuggoth (1929–30) which described the contrasting vegetation on alien dream-worlds. Summary The "Mi-go" are large, pinkish, fungoid, crustacean-like entities the size of a man; where a head would be, they have a "convoluted ellipsoid" composed of pyramided, fleshy rings and covered in antennae. According to two reports in the original short story, their bodies consist of a form of matter that does not occur naturally on Earth; for this reason, they do not register on ordinary photographic film. They are capable of going into suspended animation until softened and reheated by the sun or some other source of heat. They are about five feet (1.5 m) long, and their crustacean-like bodies bear numerous sets of paired appendages. They possess a pair of membranous bat-like wings which are used to fly through the "aether" of outer space (a scientific concept which is now discredited). The wings do not function well on Earth. Several other races in Lovecraft's Mythos also have wings like these. The Mi-go can transport humans from Earth to Pluto (and beyond) and back again by removing the subject's brain and placing it into a "brain cylinder", which can be attached to external devices to allow it to see, hear, and speak. -

Cthulhu Lives!: a Descriptive Study of the H.P. Lovecraft Historical Society

CTHULHU LIVES!: A DESCRIPTIVE STUDY OF THE H.P. LOVECRAFT HISTORICAL SOCIETY J. Michael Bestul A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Dr. Jane Barnette, Advisor Prof. Bradford Clark Dr. Marilyn Motz ii ABSTRACT Dr. Jane Barnette, Advisor Outside of the boom in video game studies, the realm of gaming has barely been scratched by academics and rarely been explored in a scholarly fashion. Despite the rich vein of possibilities for study that tabletop and live-action role-playing games present, few scholars have dug deeply. The goal of this study is to start digging. Operating at the crossroads of art and entertainment, theatre and gaming, work and play, it seeks to add the live-action role-playing game, CTHULHU LIVES, to the discussion of performance studies. As an introduction, this study seeks to describe exactly what CTHULHU LIVES was and has become, and how its existence brought about the H.P. Lovecraft Historical Society. Simply as a gaming group which grew into a creative organization that produces artifacts in multiple mediums, the Society is worthy of scholarship. Add its humble beginnings, casual style and non-corporate affiliation, and its recent turn to self- sustainability, and the Society becomes even more interesting. In interviews with the artists behind CTHULHU LIVES, and poring through the archives of their gaming experiences, the picture develops of the journey from a small group of friends to an organization with influences and products on an international scale. -

The Weird and Monstrous Names of HP Lovecraft Christopher L Robinson HEC-Paris, France

names, Vol. 58 No. 3, September, 2010, 127–38 Teratonymy: The Weird and Monstrous Names of HP Lovecraft Christopher L Robinson HEC-Paris, France Lovecraft’s teratonyms are monstrous inventions that estrange the sound patterns of English and obscure the kinds of meaning traditionally associ- ated with literary onomastics. J.R.R. Tolkien’s notion of linguistic style pro- vides a useful concept to examine how these names play upon a distance from and proximity to English, so as to give rise to specific historical and cultural connotations. Some imitate the sounds and forms of foreign nomen- clatures that hold “weird” connotations due to being linked in the popular imagination with kabbalism and decadent antiquity. Others introduce sounds-patterns that lie outside English phonetics or run contrary to the phonotactics of the language to result in anti-aesthetic constructions that are awkward to pronounce. In terms of sense, teratonyms invite comparison with the “esoteric” words discussed by Jean-Jacques Lecercle, as they dimi- nish or obscure semantic content, while augmenting affective values and heightening the reader’s awareness of the bodily production of speech. keywords literary onomastics, linguistic invention, HP Lovecraft, twentieth- century literature, American literature, weird fiction, horror fiction, teratology Text Cult author H.P. Lovecraft is best known as the creator of an original mythology often referred to as the “Cthulhu Mythos.” Named after his most popular creature, this mythos is elaborated throughout Lovecraft’s poetry and fiction with the help of three “devices.” The first is an outlandish array of monsters of extraterrestrial origin, such as Cthulhu itself, described as “vaguely anthropoid [in] outline, but with an octopus-like head whose face was a mass of feelers, a scaly, rubbery-looking body, prodigious claws on hind and fore feet, and long, narrow wings behind” (1963: 134). -

Lovecraft, New Materialism and the Maeriality of Writing Brad Tabas

Reading in the chtuhulucene: lovecraft, new materialism and the maeriality of writing Brad Tabas To cite this version: Brad Tabas. Reading in the chtuhulucene: lovecraft, new materialism and the maeriality of writing. Motifs, la revue HCTI, HCTI-Université de Bretagne occidentale, Brest, 2017. hal-02052305 HAL Id: hal-02052305 https://hal-ensta-bretagne.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02052305 Submitted on 28 Feb 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Motifs n° 2 (2017), Matérialité et Écriture READING IN THE CHTUHULUCENE: LOVECRAFT, NEW MATERIALISM AND THE MATERIALITY OF WRITING GIVING LIFE BACK TO MATTER The traditional take on the theme of the materiality of writing asks about the meaning of the material that supports human-made signs. It considers the importance of the dark side of the signifier; of all that one does not take into account when one sees a sign as a sign. It might consider the ways in which written words present one with multiple possible significations, the ways in which the fact of a text’s having been written haunts readers’ engagements with that text. Traditional theorists of the materiality of writing might remind us that this materia- lity really does have a signification, that paper and pixels really do convey meaning.