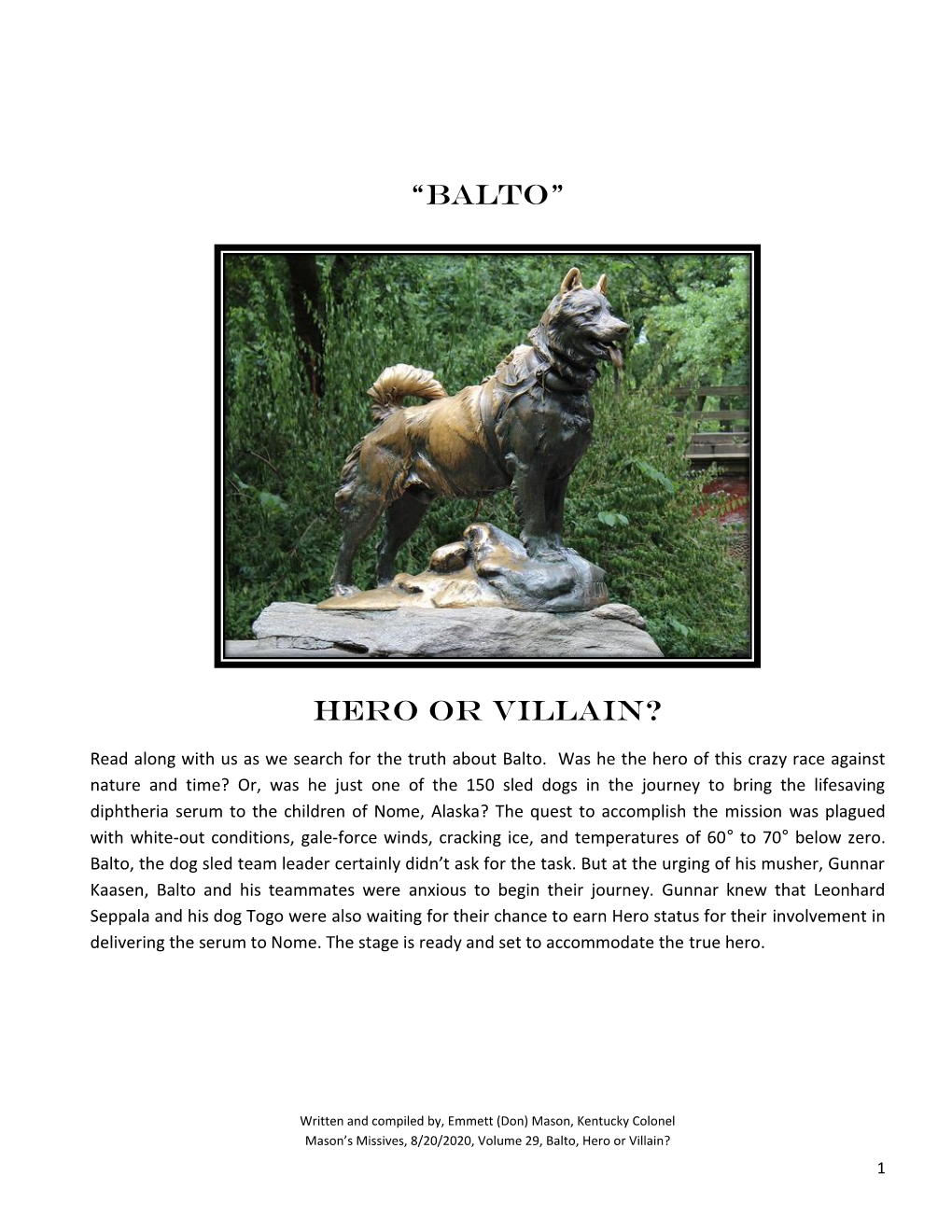

“Balto” Hero OR VILLAIN?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diary James Wickersham Aug 22, 1918 – Jan

Alaska State Library – Historical Collections Diary of James Wickersham MS 107 BOX 5 DIARY 30 Aug 22, 1918 – Jan. 3, 1919 [cover] Diary James Wickersham Aug 22, 1918 – Jan. 3, 1919 Diary 30, 1918 Aug 23, 1918 August 23 Arrived-in Tanana forenoon and went to Lower House kept by Joe. Aincich. Came up from Ruby on the launch “Sibilla” - N.C. Mail launch. Find much hostility to me here engendered and cultivated by White Pass & the N.C. Co's, and b y Gov. Riggs who is here making Sulzers campaign. There is a Reception to Riggs & wife tonight so I will not speak till tomorrow evening. Am visiting around and renewing my acquaintance with the people. Diary 30, 1918 Aug 24, 1918. August 24 My 61st Birthday Will speak tonight at the Moose Hall - Dinner with Andrew Vachon & wife. Spoke tonight to a good crowd at Moose Hall. Had a very friendly reception and am much encouraged though the Gov. & the White Pass & N.C. officials are moving every element possible against me. Attacked all three of them fairly but strongly in my speech & was earnestly supported by the audience. Noticed Father's Jette & Perron, Capt. Lenoir a many others in the Hall. Am satisfied with my speech Diary 30, 1918 Aug 25th August 25 Attended services at Father Jettes church - He preached a beautiful sermon on the sin of covetousness. The “Alaska” will be here this afternoon & will go up the river to Hot Springs on her. Was requested to make 4 Minute talk at Post tonight at picture show - did it badly! Boarded “Alaska” for the Hot Springs at midnight. -

Engineered Mushing Cooker

Portland State University PDXScholar Maseeh College of Engineering & Computer Undergraduate Research & Mentoring Program Science 2016 Engineered Mushing Cooker Aimee Ritter Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/mcecs_mentoring Part of the Materials Science and Engineering Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Ritter, Aimee, "Engineered Mushing Cooker" (2016). Undergraduate Research & Mentoring Program. 6. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/mcecs_mentoring/6 This Poster is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Research & Mentoring Program by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Iditarod Class Cooker for Dog Mushing Aimee Ritter and Tom Bennett INTRODUCTION: STANDARD TEST PROCEDURE: TESTS ON MOUNT HOOD: The Iditarod is a dog sled race that spans almost 1,000 miles of • 8L water at tap temperature (~60F) The graph below shows the changes in temperature of the water pan over Alaskan wilderness. The racers, also known as mushers, are allowed a • 1 bottle of HEET (355mL) shared equally in burners the course of the test. Each peak is when all the snow melted to water and 16 dog team at the start in Willow, AK. From there they take a little started warming up. All the troughs are when I added snow to the water Methanol Combustion: over a week to get from end to end facing temperatures of 60 below pan to reach the maximum capacity of the pan. By the end of the test (all zero and elevation gains over 3,000 feet. -

2016 Media Guide

2016 MEDIA GUIDE 1 2 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................................................... 4 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................................... 7 IDITAROD BOARD OF DIRECTORS, STAFF & COORDINATORS .................................................................................. 11 PARTNERS/SPONSORS ........................................................................................................................................... 12 MEDIA INFORMATION ........................................................................................................................................... 13 2016 MEDIA AND CREDENTIAL GUIDELINES ........................................................................................................... 14 MEDIA FAQ ............................................................................................................................................................ 17 IDITAROD FACTS .................................................................................................................................................... 21 IDITAROD HISTORY ................................................................................................................................................ 24 IDITAROD RACE HEADQUARTERS CONTACT INFORMATION .................................................................................. -

Alaskan Sled Dog Tales: True Stories of the Steadfast Companions of the North Country Online

QIcx6 (Online library) Alaskan Sled Dog Tales: True Stories of the Steadfast Companions of the North Country Online [QIcx6.ebook] Alaskan Sled Dog Tales: True Stories of the Steadfast Companions of the North Country Pdf Free Helen Hegener *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks #1750865 in Books 2016-05-02Original language:English 9.00 x .73 x 6.00l, .95 #File Name: 0692668470320 pages | File size: 20.Mb Helen Hegener : Alaskan Sled Dog Tales: True Stories of the Steadfast Companions of the North Country before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Alaskan Sled Dog Tales: True Stories of the Steadfast Companions of the North Country: 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. This one makes it to Nome in style!By G. M. WaltonIf you love sled dogs, adventure, the North Lands, and/or history, this is a book for you. Ms Hegener knows her subject forward and backward and writes about it in an engaging and informative way. She has collected an amazing bunch of photographs, old magazine covers, postcards and other memorabilia which illustrate and enhance this absorbing narrative. You will meet many of Alaska's notable characters and some who have never received the fame and acclaim they deserve as well as a few shining examples of the incredible dogs who made Alaska what it is today. If you loved White Fang or some of the modern mushers' personal tales, you will get even more and deeper insights from this beautifully presented book. -

Special Edition Inside

A Publication by The American Society for the Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics Pharmacologist Inside: Feature articles from 2014-2015 Special Edition VISIT THE ASPET CAREER CENTER TODAY! WWW.ASPET.ORG/CAREERCENTER/ 4 5 12 21 30 41 WHAT YOU NEED: ASPET’S CAREER CENTER HAS IT 52 Jobseekers: Employers: No registration fee Searchable résumé database Advanced search options Hassle-free posting; online account management tools 61 Sign up for automatic email notifi cations of new jobs that Reach ASPET’s Twitter followers (over 1,000), match your criteria LinkedIn Members (over 2,000), and email subscribers (over 4,000) Free & confi dential résumé posting 71 Post to just ASPET or to entire NHCN network Access to jobs posted on the National Healthcare Career Network (NHCN) Sign up for automatic email notifications of new résumés that match your criteria Career management resources including career tips, coaching, résumé writing, online profi le development, Job activity tracking and much more ASPET is committed to your success: The ASPET Career Center is the best resource for matching job seekers and employers in the pharmacology and related health science fi elds. Our vast range of resources and tools will help you look for jobs, fi nd great employees, and proactively manage 9650 Rockville Pike, Bethesda, MD 20814-3995 your career goals. Main Office: 301.634.7060 www.aspet.org ASPET Career Center Full Page Ad 2015 Updated.indd 1 1/15/2016 3:18:16 PM The Pharmacologist is published and distributed by the American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. THE PHARMACOLOGIST VISIT THE ASPET CAREER CENTER TODAY! PRODUCTION TEAM Rich Dodenhoff Catherine Fry, PhD WWW.ASPET.ORG/CAREERCENTER/ Judith A. -

Club Events 2011

Club Events 2011 Thanks you to all the clubs who held AKC Responsible Dog Ownership Day events. With over 600 events reported to us from across the country, the celebration was a huge success! Below, please enjoy some event recaps and photos submitted by some of our event holding clubs. If you would like to submit your event photos and recaps for consideration, please email [email protected]. Albuquerque Whippet Fanciers Association Albuquerque Whippet Fanciers Association (AWFA) held its 2nd annual RDOD in conjunction with its first-ever Coursing Ability (CA) trial! All exhibitors and spectators received RDOD goodies, AKC brochures, and got to watch a wide variety of dogs run in this fun new event. A wide variety of breeds participated, including a Border Terrier, Boxer, Dachshund, Doberman and Dalmatian. A great time was had by all! The Doberman, Dazzle, was the first dog to earn in a CA leg in NM! AWFA also held an informal "Meet the Breed" as a part of its RDOD event, with a wide variety of sighthounds on hand, including the Azawakh, Borzoi, Greyhound, Saluki, Scottish Deerhound and Whippet. The club members look forward to including RDOD in their 2012 fall event. - Leonore Abordo, President Animal Care and Reproductive Services, LLC. Animal Care and Reproductive Services, LLC hosted an RDO Day on September 10, 2011. A number of breed clubs and the local Obedience club participated. A surprise visit from Sparky the Fire Dog was a big hit. A number of dogs participated in the massage therapy and attendees enjoyed the “Stuffed Toy Dog Show.” The event also raised $75 for the AKC Canine Health Foundation via a bake sale and raffle. -

The Iditarod Trail Dog Sled Race

Reading Comprehension/ Sports Name ___________________________________________ Date _________________ THE IDITAROD TRAIL DOG SLED RACE The “Iditarod” is a dog sled race that is held every year in Alaska in March. Dog sled racing is a sport, and the Iditarod is one of the most difficult races. In a dog sled race, a group of dogs pull a sled across the snow, guided by a person who stands on the sled behind the dogs. The race may be short (called a sprint race) or long. In the Iditarod, the racers take about ten days to cover a distance over 1150 miles (1,852 km). Dog sled racing is a type of mushing. Mushing refers to any type of dog pulling any kind of transport across the snow. Mushing is used to move materials (including the mail) over snow-covered ground that cars, trains, and other transportation cannot get over. People who drive dog sleds are called mushers. In mushing, dogs are harnessed, or hooked up, to the sled. There may be only one dog or many dogs. The number depends on how much is being pulled and how far, the type of ground, and the reason that the dog is pulling. The type of dog also depends on the load and the purpose. If the load is heavy, more dogs are used. If it is important to go far, then strong dogs are used. If it is important to go fast, dogs that can run very quickly are used. If the team is big, it’s important that the dogs be calm and able to work in groups. -

VITAL RECORDS from ALASKA DAILY EMPIRE 1921-1925 JUNEAU, ALASKA VOLUME II Compiled by Betty J. Miller Copyright May 1996 All

VITAL RECORDS FROM ALASKA DAILY EMPIRE 1921-1925 JUNEAU, ALASKA VOLUME II Compiled by Betty J. Miller Copyright May 1996 All Rights Reserved Betty J. Miller 2551 Vista Drive #C-201 Juneau, Alaska 99801 FOREWORD Another two years out of my busy life and Volume II is completed! This reference book covers vital statistical records abstracted from the Juneau Alaska Daily Empire from 1921 through 1925. The response and sales of Volume I (1916-1920) certainly was an encouragement for me to continue the research. I suspect there will be a Volume III sometime in the future. Keep in mind when perusing the alphabetical index that the names appearing there are exactly the way they were printed in the newspaper, i.e. some were incorrectly spelled. Check the variations of spellings for surnames. I've cross-referenced where I detected misspellings. It helps to have lived in Juneau all my life and have an awareness of some of these long-time Juneau family names. Copies of these newspaper articles referenced in this book can be made at the Alaska State Library at [email protected] or 907-465-2920 in Juneau. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wouldn't be able to undertake these projects without the cooperation of the Alaska State Library allowing me to take microfilm from their library for weeks at a time. Once again the Family History Center at the LDS Church allowed me to use their library and microfilm reader whenever I needed—which was a couple hours every day. My wonderful husband helped me proofread while we were on vacation this winter. -

Iditarod National Historic Trail I Historic Overview — Robert King

Iditarod National Historic Trail i Historic Overview — Robert King Introduction: Today’s Iditarod Trail, a symbol of frontier travel and once an important artery of Alaska’s winter commerce, served a string of mining camps, trading posts, and other settlements founded between 1880 and 1920, during Alaska’s Gold Rush Era. Alaska’s gold rushes were an extension of the American mining frontier that dates from colonial America and moved west to California with the gold discovery there in 1848. In each new territory, gold strikes had caused a surge in population, the establishment of a territorial government, and the development of a transportation system linking the goldfields with the rest of the nation. Alaska, too, followed through these same general stages. With the increase in gold production particularly in the later 1890s and early 1900s, the non-Native population boomed from 430 people in 1880 to some 36,400 in 1910. In 1912, President Taft signed the act creating the Territory of Alaska. At that time, the region’s 1 Iditarod National Historic Trail: Historic Overview transportation systems included a mixture of steamship and steamboat lines, railroads, wagon roads, and various cross-country trail including ones designed principally for winter time dogsled travel. Of the latter, the longest ran from Seward to Nome, and came to be called the Iditarod Trail. The Iditarod Trail today: The Iditarod trail, first commonly referred to as the Seward to Nome trail, was developed starting in 1908 in response to gold rush era needs. While marked off by an official government survey, in many places it followed preexisting Native trails of the Tanaina and Ingalik Indians in the Interior of Alaska. -

Central Park

Hunter College Geology Field Trip Central Park Shruti Philips Field Trip stops in Central Park Stop #1 N Stop #2 Enter CP here on 5th Ave Stop #3 Between 66th Stop #2 and 67th street Field trip Stop #1 path Stop #3 Enter the Park from 5th Ave between 66th and 67th street Walk past the Billy Johnson Playground (on your right) and approach a small intersection. You will see a rock exposure ahead of you. Stop-1 Outcrop A Foliated metamorphic Rock Outcrop A Foliated metamorphic Rock STOP-1: Outcrop A The direction of foliation at stop-1 Click on the video to see the direction of foliation on a compass. This rock displays layering (foliation) on the outcrop scale as well as the hand specimen scale Foliation displays differential weathering Why do we see these high-grade metamorphic rocks on the surface in Central Park? A map of the world 449 Million years ago when the rocks in Central Park were forming Note that New York is ~20 0 S of the equator at that time. It was a shallow seafloor then accumulating sediments. How the rocks in Central Park formed and metamorphosed during the Paleozoic Era About 400 million year ago, this region was shallow sea floor, off the coast of the American Continent, and was the site of deposition of great thicknesses of sediment derived from the erosion of the nearby land (Fig. 1). Fig. 2: A new, convergent plate boundary developed here, along which ocean lithosphere was pushed under continental lithosphere (forming a subduction zone). -

Qualitative Changes in Ethno-Linguistic Status : a Case Study of the Sorbs in Germany

Qualitative Changes in Ethno-linguistic Status: A Case Study of the Sorbs in Germany by Ted Cicholi RN (Psych.), MA. Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Political Science School of Government 22 September 2004 Disclaimer Although every effort has been taken to ensure that all Hyperlinks to the Internet Web sites cited in this dissertation are correct at the time of writing, no responsibility can be taken for any changes to these URL addresses. This may change the format as being either underlined, or without underlining. Due to the fickle nature of the Internet at times, some addresses may not be found after the initial publication of an article. For instance, some confusion may arise when an article address changes from "front page", such as in newspaper sites, to an archive listing. This dissertation has employed the Australian English version of spelling but, where other works have been cited, the original spelling has been maintained. It should be borne in mind that there are a number of peculiarities found in United States English and Australian English, particular in the spelling of a number of words. Interestingly, not all errors or irregularities are corrected by software such as Word 'Spelling and Grammar Check' programme. Finally, it was not possible to insert all the accents found in other languages and some formatting irregularities were beyond the control of the author. Declaration This dissertation does not contain any material which has been accepted for the award of any other higher degree or graduate diploma in any tertiary institution. -

And the Legacy of the Serum Run

Baltoand the Legacy of the Serum Run 1 WADE OVAL DRIVE, UNIVERSITY CIRCLE CLEVELAND, OHIO 44106 216.231.4600 800.317.9155 WWW.CMNH.ORG Nome, Alaska, appeared on the map during one of the world’s great gold rushes at the end of the 19th century. Located on the Seward Peninsula, the town’s population had swelled to 20,000 by 1900 after gold was discovered on beaches along the Bering Sea. By 1925, however, much of the gold was gone and scarcely 1,400 people were left in the remote northern outpost. Nome was icebound seven months of the year and the nearest railroad was more than 650 miles away, in the town of Nenana. The radio telegraph was the most reliable means by which Nome could communicate with the rest of the world during the winter. Since Alaska was a U.S. territory, the government also maintained a route over which relays of dog teams carried mail from Anchorage to Nome. A one- way trip along this path, called the Iditarod Trail, took about a month. The “mushers” who traversed the trail were the best in Alaska. A RACE FOR LIFE JANUarY 27 The serum arrived in Nenana by train, and the relay to the On January 20, 1925, a radio signal went out, carried for stricken city began. “Wild Bill” Shannon lashed the life- miles across the frozen tundra: saving cargo to his sled and set off westward. Except for the Nom e c alling... dogs’ panting and the swooshing of runners on the snow, No m e c alling..