The Political Thought of Tahir-Ul-Qadri in Its Islamic Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Election 2018 Update-Ii - Fafen General Election 2018

GENERAL ELECTION 2018 UPDATE-II - FAFEN GENERAL ELECTION 2018 Update-II April 01 – April 30, 2018 1. BACKGROUND AND INTRODUCTION Free and Fair Election Network (FAFEN) initiated its assessment of the political environment and implementation of election-related laws, rules and regulations in January 2018 as part of its multi-phase observation of General Election (GE) 2018. The purpose of the observation is to contribute to the evolution of an election process that is free, fair, transparent and accountable, in accordance with the requirements laid out in the Elections Act, 2017. Based on its observation, FAFEN produces periodic updates, information briefs and reports in an effort to provide objective, unbiased and evidence-based information about the quality of electoral and political processes to the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP), political parties, media, civil society organizations and citizens. General Election 2018 Update-II is based on information gathered systematically in 130 districts by as many trained and non-partisan District Coordinators (DCs) through 560 interviews1 with representatives of 33 political parties and groups and 294 interviews with representative of 35 political parties and groups over delimitation process. The Update also includes the findings of observation of 559 political gatherings and 474 ECP’s centres set up for the display of preliminary electoral rolls. FAFEN also documented the formation of 99 political alliances, party-switching by political figures, and emerging alliances among ethnic, tribal and professional groups. In addition, the General Election 2018 Update-II comprises data gathered through systematic monitoring of 86 editions of 25 local, regional and national newspapers to report incidents of political and electoral violence, new development schemes and political advertisements during April 2018. -

Pakistan, Country Information

Pakistan, Country Information PAKISTAN ASSESSMENT April 2003 Country Information and Policy Unit I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT II GEOGRAPHY III ECONOMY IV HISTORY V STATE STRUCTURES VI HUMAN RIGHTS VIA. HUMAN RIGHTS ISSUES VIB. HUMAN RIGHTS - SPECIFIC GROUPS VIC. HUMAN RIGHTS - OTHER ISSUES ANNEX A: CHRONOLOGY OF MAJOR EVENTS ANNEX B: POLITICAL ORGANISATIONS AND OTHER GROUPS ANNEX C: PROMINENT PEOPLE ANNEX D: REFERENCES TO SOURCE MATERIAL 1. SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 This assessment has been produced by the Country Information and Policy Unit, Immigration and Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a wide variety of recognised sources. The document does not contain any Home Office opinion or policy. 1.2 The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum / human rights determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum / human rights claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.3 The assessment is sourced throughout. It is intended to be used by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. These sources have been checked for currency, and as far as can be ascertained, remained relevant and up to date at the time the document was issued. 1.4 It is intended to revise the assessment on a six-monthly basis while the country remains within the top 35 asylum-seeker producing countries in the United Kingdom. 2. GEOGRAPHY file:///V|/vll/country/uk_cntry_assess/apr2003/0403_Pakistan.htm[10/21/2014 9:56:32 AM] Pakistan, Country Information General 2.1 The Islamic Republic of Pakistan lies in southern Asia, bordered by India to the east and Afghanistan and Iran to the west. -

The Muslim 500 2011

The Muslim 500 � 2011 The Muslim The 500 The Muslim 500 � 2011 The Muslim The 500 The Muslim 500The The Muslim � 2011 500———————�——————— THE 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS ———————�——————— � 2 011 � � THE 500 MOST � INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · All rights reserved. No part of this book may be repro- The Muslim 500: The 500 Most Influential Muslims duced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic 2011 (First Edition) or mechanic, inclding photocopying or recording or by any ISBN: 978-9975-428-37-2 information storage and retrieval system, without the prior · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · written permission of the publisher. Views expressed in The Muslim 500 do not necessarily re- Chief Editor: Prof. S. Abdallah Schleifer flect those of RISSC or its advisory board. Researchers: Aftab Ahmed, Samir Ahmed, Zeinab Asfour, Photo of Abdul Hakim Murad provided courtesy of Aiysha Besim Bruncaj, Sulmaan Hanif, Lamya Al-Khraisha, and Malik. Mai Al-Khraisha Image Copyrights: #29 Bazuki Muhammad / Reuters (Page Designed & typeset by: Besim Bruncaj 75); #47 Wang zhou bj / AP (Page 84) Technical consultant: Simon Hart Calligraphy and ornaments throughout the book used courtesy of Irada (http://www.IradaArts.com). Special thanks to: Dr Joseph Lumbard, Amer Hamid, Sun- dus Kelani, Mohammad Husni Naghawai, and Basim Salim. English set in Garamond Premiere -

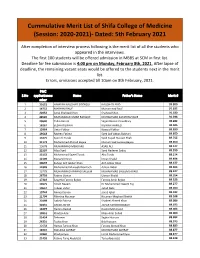

Cumulative Merit List

Cummulative Merit List of Shifa College of Medicine (Session: 2020-2021)- Dated: 5th February 2021 After completion of interview process following is the merit list of all the students who appeared in the interviews. The first 100 students will be offered admission in MBBS at SCM in first list. Deadline for fee submission is 4:00 pm on Monday, February 8th, 2021. After lapse of deadline, the remaining vacant seats would be offered to the students next in the merit list. Errors, omissions accepted till 10am on 8th February, 2021. PMC S.No applicationnu Name Father's Name Merit # mber 1 21623 HAMZAH NAUSHAD SIDDIQUI NAUSHAD ABID 93.200 2 14752 MARYAM RAUF Muhammad Rauf 91.632 3 22652 Amal Shahzad Khan Shahzad Khan 91.180 4 28526 MUHAMMAD UMAR RAFIQUE MUHAMMAD ZAFAR RAFIQUE 91.036 5 20640 Talha Rasool Sajjad Rasool Chaudhary 90.282 6 18267 EESHA RIZWAN RIZWAN AHMED 90.045 7 12964 Umar Fakhar Nawaid Fakhar 89.890 8 19618 Raveen Fatima Syed Asif Abbas Bukhari 89.850 9 13475 Syed Ali Turab Syed Sajjad Hussain Shah 89.755 10 31173 Muhammad Ahmed Bajwa Muhammad Farooq Bajwa 89.650 11 13678 MUHAMMAD MEHDI ALI ASAD ALI 89.577 12 21597 Aliza Syed Syed Nadeem Sadiq 89.559 13 15152 Muhammad Sajeel Turab Abu Turab 89.514 14 12109 Manahil Imran Imran Khalid 89.494 15 30637 Zuhayr Arif Jabbar Khan Arif Jabbar Khan 89.477 16 11849 Muhammad Muneeb Warriach Adnan Akbar 89.464 17 13779 MUHAMMAD AMMAD SALEEM MUHAMMAD SALEEM JAVAID 89.427 18 26793 Fatima Usman Usman Khalid 89.354 19 17319 Sayyeda Farooq Bajwa Farooq Amin Bajwa 89.323 20 13675 Alizeh Naeem -

Heralding a New Enlightenment

Conceptualizing the development of personality in children: An analysis of Islamic philosophy and contemporary Western psychology Muhammad Tahir and Stephan Larmar* Abstract: The paper aims to examine the concept of child personality development from the perspectives of Islamic philosophy and contemporary Western psychology. In recent decades, the parental journey associated with the healthy development of children has become increasingly complex and sometimes stressful across all societies and communities of the world. Major world religions and social sciences delineated various aspects and perspectives relating to sound personality development in children. The present article seeks to present the findings of a study that found to give an overview of fundamental principles related to child personality development drawn from Islamic philosophy and contemporary Western psychology. Drawing on these two perspectives, the paper seeks to explain personality development, highlighting both similarities and differences associated with these perspectives. The study employed qualitative content analysis to explore relevant data from the Qur’anic verses and Prophetic traditions, as well as theoretical studies and empirical research of psychology. The research findings predominantly highlight an integrated approach towards child personality development as framed within the perspective of Islamic philosophy and contemporary Western psychological understandings. The paper serves to link Islamic thought to contemporary Western psychological aspects -

Pakistan's Violence

Pakistan’s Violence Causes of Pakistan’s increasing violence since 2001 Anneloes Hansen July 2015 Master thesis Political Science: International Relations Word count: 21481 First reader: S. Rezaeiejan Second reader: P. Van Rooden Studentnumber: 10097953 1 Table of Contents List of Abbreviations and Acronyms List of figures, Maps and Tables Map of Pakistan Chapter 1. Introduction §1. The Case of Pakistan §2. Research Question §3. Relevance of the Research Chapter 2. Theoretical Framework §1. Causes of Violence §1.1. Rational Choice §1.2. Symbolic Action Theory §1.3. Terrorism §2. Regional Security Complex Theory §3. Colonization and the Rise of Institutions §4. Conclusion Chapter 3. Methodology §1. Variables §2. Operationalization §3. Data §4. Structure of the Thesis Chapter 4. Pakistan §1. Establishment of Pakistan §2. Creating a Nation State §3. Pakistan’s Political System §4. Ethnicity and Religion in Pakistan §5. Conflict and Violence in Pakistan 2 §5.1. History of Violence §5.2. Current Violence §5.2.1. Baluchistan §5.2.2. Muslim Extremism and Violence §5. Conclusion Chapter 5. Rational Choice in the Current Conflict §1. Weak State §2. Economy §3. Instability in the Political Centre §4. Alliances between Centre and Periphery §5. Conclusion Chapter 6. Emotions in Pakistan’s Conflict §1. Discrimination §2. Hatred towards Others §2.1. Political Parties §2.2 Extremist Organizations §3. Security Dilemma §4. Conclusion Chapter 7. International Influences §1. International Relations §1.1. United States – Pakistan Relations §1.2. China – -

Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan

Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan in Pakistan and Militancy Religion a report of the csis program on crisis, conflict, and cooperation Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan a literature review 1800 K Street, NW | Washington, DC 20006 Project Director Tel: (202) 887-0200 | Fax: (202) 775-3199 Robert D. Lamb E-mail: [email protected] | Web: www.csis.org Author Mufti Mariam Mufti June 2012 ISBN 978-0-89206-700-8 CSIS Ë|xHSKITCy067008zv*:+:!:+:! CHARTING our future a report of the csis program on crisis, conflict, and cooperation Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan a literature review Project Director Robert L. Lamb Author Mariam Mufti June 2012 CHARTING our future About CSIS—50th Anniversary Year For 50 years, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has developed practical solutions to the world’s greatest challenges. As we celebrate this milestone, CSIS scholars continue to provide strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to help decisionmakers chart a course toward a better world. CSIS is a bipartisan, nonprofit organization headquartered in Washington, D.C. The Center’s 220 full-time staff and large network of affiliated scholars conduct research and analysis and de- velop policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. Since 1962, CSIS has been dedicated to finding ways to sustain American prominence and prosperity as a force for good in the world. After 50 years, CSIS has become one of the world’s pre- eminent international policy institutions focused on defense and security; regional stability; and transnational challenges ranging from energy and climate to global development and economic integration. -

Freedom of Religion & Religious Minorities in Pakistan: a Study Of

Fordham International Law Journal Volume 19, Issue 1 1995 Article 5 Freedom of Religion & Religious Minorities in Pakistan: A Study of Judicial Practice Tayyab Mahmud∗ ∗ Copyright c 1995 by the authors. Fordham International Law Journal is produced by The Berke- ley Electronic Press (bepress). http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ilj Freedom of Religion & Religious Minorities in Pakistan: A Study of Judicial Practice Tayyab Mahmud Abstract Pakistan’s successive constitutions, which enumerate guaranteed fundamental rights and pro- vide for the separation of state power and judicial review, contemplate judicial protection of vul- nerable sections of society against unlawful executive and legislative actions. This Article focuses upon the remarkably divergent pronouncements of Pakistan’s judiciary regarding the religious status and freedom of religion of one particular religious minority, the Ahmadis. The superior judiciary of Pakistan has visited the issue of religious freedom for the Ahmadis repeatedly since the establishment of the State, each time with a different result. The point of departure for this ex- amination is furnished by the recent pronouncement of the Supreme Court of Pakistan (”Supreme Court” or “Court”) in Zaheeruddin v. State,’ wherein the Court decided that Ordinance XX of 1984 (”Ordinance XX” or ”Ordinance”), which amended Pakistan’s Penal Code to make the public prac- tice by the Ahmadis of their religion a crime, does not violate freedom of religion as mandated by the Pakistan Constitution. This Article argues that Zaheeruddin is at an impermissible variance with the implied covenant of freedom of religion between religious minorities and the Founding Fathers of Pakistan, the foundational constitutional jurisprudence of the country, and the dictates of international human rights law. -

Conferment of Pakistan Civil Awards - 14Th August, 2020

F. No. 1/1/2020-Awards-I GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN CABINET SECRETARIAT (CABINET DIVISION) ***** PRESS RELEASE CONFERMENT OF PAKISTAN CIVIL AWARDS - 14TH AUGUST, 2020 On the occasion of Independence Day, 14th August, 2020, the President of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan has been pleased to confer the following ‘Pakistan Civil Awards’ on citizens of Pakistan as well as Foreign Nationals for showing excellence and courage in their respective fields. The investiture ceremony of these awards will take place on Pakistan Day, 23rd March, 2021:- S. No. Name of Awardee Field 1 2 3 I. NISHAN-I-IMTIAZ 1 Mr. Sadeqain Naqvi Arts (Painting/Sculpture) 2 Prof. Shakir Ali Arts (Painting) 3 Mr. Zahoor ul Haq (Late) Arts (Painting/ Sculpture) 4 Ms. Abida Parveen Arts (Singing) 5 Dr. Jameel Jalibi Literature Muhammad Jameel Khan (Late) (Critic/Historian) (Sindh) 6 Mr. Ahmad Faraz (Late) Literature (Poetry) (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) II. HILAL-I-IMTIAZ 7 Prof. Dr. Anwar ul Hassan Gillani Science (Pharmaceutical (Sindh) Sciences) 8 Dr. Asif Mahmood Jah Public Service (Punjab) III. HILAL-I-QUAID-I-AZAM 9 Mr. Jack Ma Services to Pakistan (China) IV. SITARA-I-PAKISTAN 10 Mr. Kyu Jeong Lee Services to Pakistan (Korea) 11 Ms. Salma Ataullahjan Services to Pakistan (Canada) V. SITARA-I-SHUJA’AT 12 Mr. Jawwad Qamar Gallantry (Punjab) 13 Ms. Safia (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) 14 Mr. Hayatullah Gallantry (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) 15 Malik Sardar Khan (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) 16 Mr. Mumtaz Khan Dawar (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) 17 Mr. Hayat Ullah Khan Dawar Hurmaz Gallantry (Shaheed) (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) 18 Malik Muhammad Niaz Khan (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) 19 Sepoy Akhtar Khan (Shaheed) Gallantry (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) 20 Mr. -

Characterization of Rifampicin-Resistant Mycobacterium

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Characterization of rifampicin‑resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan Anwar Sheed Khan1,2, Jody E. Phelan3, Muhammad Tahir Khan4, Sajid Ali2, Muhammad Qasim1, Gary Napier3, Susana Campino3, Sajjad Ahmad5, Otavio Cabral‑Marques6,7,8, Shulin Zhang9, Hazir Rahman10, Dong‑Qing Wei11, Taane G. Clark3,12* & Taj Ali Khan5* Tuberculosis (TB), caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, is endemic in Pakistan. Resistance to both frstline rifampicin and isoniazid drugs (multidrug‑resistant TB; MDR‑TB) is hampering disease control. Rifampicin resistance is attributed to rpoB gene mutations, but rpoA and rpoC loci may also be involved. To characterise underlying rifampicin resistance mutations in the TB endemic province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, we sequenced 51 M. tuberculosis isolates collected between 2016 and 2019; predominantly, MDR‑TB (n = 44; 86.3%) and lineage 3 (n = 30, 58.8%) strains. We found that known mutations in rpoB (e.g. S405L), katG (e.g. S315T), or inhA promoter loci explain the MDR‑TB. There were 24 unique mutations in rpoA, rpoB, and rpoC genes, including four previously unreported. Five instances of within‑host resistance diversity were observed, where two were a mixture of MDR‑TB strains containing mutations in rpoB, katG, and the inhA promoter region, as well as compensatory mutations in rpoC. Heteroresistance was observed in two isolates with a single lineage. Such complexity may refect the high transmission nature of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa setting. Our study reinforces the need to apply sequencing approaches to capture the full‑extent of MDR‑TB genetic diversity, to understand transmission, and to inform TB control activities in the highly endemic setting of Pakistan. -

Effects of Lysine Levels with Digestible Amino Acids on Growth Performance, Carcass Evaluation, Productive and Reproductive Traits of Aseel Chicken

EFFECTS OF LYSINE LEVELS WITH DIGESTIBLE AMINO ACIDS ON GROWTH PERFORMANCE, CARCASS EVALUATION, PRODUCTIVE AND REPRODUCTIVE TRAITS OF ASEEL CHICKEN MUNAWAR HUSSAIN 2014-VA-509 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN THE PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POULTRY PRODUCTION UNIVERSITY OF VETERINARY AND ANIMAL SCIENCES LAHORE, PAKISTAN 2018 To, The Controller of Examinations, University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, Lahore. We, the Supervisory Committee, certify that the contents and form of the thesis, submitted by Munawar Hussain, Reg. # 2014-VA-509 have been found satisfactory and recommend that it be processed for the evaluation by the External Examiner (s) for award of the Degree. Supervisor ___________________________________________ (Prof. Dr. Athar Mahmud) Member ___________________________________________ (Dr. Jibran Hussain) Member ___________________________________________ (Dr. Shafqat Nawaz Qaisrani) DEDICATION This work is dedicated to My Beloved Parents& Family My Teachers especially Prof. Dr. Muhammad Akram i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS All praises and thanks to ALMIGHTY ALLAH, the Lord of the worlds, the Omnipotent, the most Beneficent, the Merciful and the Gracious. Who is the creator of this world and heavens, the lord of the Day of Judgment, who is the entire source of knowledge and wisdom and endowed it to the mankind. The work described in this thesis was made possible by contributions from various individuals and institutions to whom I am indebted. I thank all those who, in different ways, have walked beside me along the way; offering support and encouragement, challenging my thinking, and teaching me to consider alternative views. The author would like to express his deep appreciation and thanks to my supervisor Prof. -

List of Election Symbols Allotted to Political Parties

116 Election Symbols Alloted to political parties 1 Aam Admi Tehreek Pakistan Mug 181 2 Aam Awam Party Wheat Bunch 322 3 Aam loeg Ittehad Pencil 196 4 Aam Log Party Pakistan Hut 144 5 All Pakistan Kissan ittehad Bulllock Cart 41 6 All Pakistan Minority Movement Pakistan Giraffe 122 7 All Pakistan Muslim League Eagle 93 8 All Pakistan Muslim League (Jinnah) Bicycle 27 9 All Pakistan Tehreek Boat 30 10 Allah-O-Akbar Tehreek Chair 55 11 Amun Taraqqi Party Tyre 309 12 Awam League Human Hand 143 13 Awami Justice Party Pakistan Tumbler 303 14 Awami Muslim League Pakistan Ink pot with Pen 146 15 Awami National Party Lantern 162 16 Awami Party Pakistan-S Aeroplane 2 17 Awami Workers Party Bulb 40 18 Balochistan Awami Party Cow 70 19 Balochistan National Party Axe 14 20 Balochistan National Party(Awami) Camel 49 21 Barabri Party Pakistan Pen 195 22 Front National Pakistan Unity 311 23 Grand Democratic Alliance Star 259 24 Hazara Democratic Party Crescent 72 25 Humdardan-e-Watan Pakistan Coat 61 26 Islami Jamhoori Ittehad Pakistan Football 108 27 Islami Tehreek Pakistan Two Sword 307 28 Ittehad-e-Ummat Pakistan Energy Saver 99 29 Jamat-e-Islami Pakistan Scale 232 30 Jamhoori Watan Party Wheel 323 31 Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam Nazaryati Pakistan Takhti 274 32 Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam Pakistan Book 31 33 Jamiat Ulema-e-Pakistan (Noorani) Key 154 34 Jamiat Ulma-e-Islam Pakistan (Imam Chitrali Cap 59 Noorani) 35 Jamiyat Ulema-e-Islam Pakistan(S) Ladder 161 36 Jamote Qaumi Movement Electric Pol 95 37 Jannat Pakistan Party Fountain 111 38 Majlis Wahdat-e-Muslimeen