Dogmatic Approaches of Qur'ān Translators

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Sustainability of Neighbourhood Masjid Development in Malaysia

SOCIAL SUSTAINABILITY OF NEIGHBOURHOOD MASJID DEVELOPMENT IN MALAYSIA TASSADUQ ABBAS MALIK UNIVERSITI TEKNOLOGI MALAYSIA SOCIAL SUSTAINABILITY OF NEIGHBOURHOOD MASJID DEVELOPMENT IN MALAYSIA TASSADUQ ABBAS MALIK A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Architecture) Faculty of Built Environment Universiti Teknologi Malaysia AUGUST 2017 iii DEDICATION “TO HUMANITY” iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Many thanks and gratitude goes to Allah Subhanwataalah, The Almighty who gave me the will, courage and means for this endeavour. After the salutations to prophet Muhammad Sallallahu allaihiwassalam, my heartfelt gratitude goes to my supervisor, Professor Dr. Mohd Hamdan Ahmad, whose advice, guidance and understanding in all situations ensured the completion of this study. I also appreciate the help and assistance of my research colleague, Samalia Adamu who always helped in keeping me on track. My doa and gratitude also goes to my parents whose training, discipline and doa made me the person who I am today. My heartfelt doa for my late wife, Dr Hajjah Zaliha Ismail, may Allah grant her high place in Jannatul Firdaus, without whom I wouldn’t be here today. I particularly appreciate the help, patience, tolerance and understanding of my wife Hajjah Noraini Hamzah, you made this thesis materialise. I thank and love you my children, Abu Turab and Dr Zille Zahra, my daughter in law Dr Nik Nurul Zilal and my granddaughter Naylaa Az Zahra, you all are my world. v FORWARD This researcher is deeply thankful and appreciates the respondents whose consent and permission to take photographs and publish it in this thesis have remarkably assisted in enriching the research findings by providing a true representation of the research. -

A Study of Kufic Script in Islamic Calligraphy and Its Relevance To

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1999 A study of Kufic script in Islamic calligraphy and its relevance to Turkish graphic art using Latin fonts in the late twentieth century Enis Timuçin Tan University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Tan, Enis Timuçin, A study of Kufic crs ipt in Islamic calligraphy and its relevance to Turkish graphic art using Latin fonts in the late twentieth century, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 1999. http://ro.uow.edu.au/ theses/1749 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. A Study ofKufic script in Islamic calligraphy and its relevance to Turkish graphic art using Latin fonts in the late twentieth century. DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by ENiS TIMUgiN TAN, GRAD DIP, MCA FACULTY OF CREATIVE ARTS 1999 CERTIFICATION I certify that this work has not been submitted for a degree to any university or institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by any other person, expect where due reference has been made in the text. Enis Timucin Tan December 1999 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I acknowledge with appreciation Dr. Diana Wood Conroy, who acted not only as my supervisor, but was also a good friend to me. I acknowledge all staff of the Faculty of Creative Arts, specially Olena Cullen, Liz Jeneid and Associate Professor Stephen Ingham for the variety of help they have given to me. -

Baha'i Faith and Its Claims

Baha’i Faith and Its Claims Bahaism and Its Claims By SAMUEL G. WILSON, M.A., P.P. Baha’ism and Its Claims. A Study of the Religions Promulgated by Baha’U’llah and Abdul Baha. Baha’i Faith is a revolt from the fold of Islam which in recent years has been bidding vigorously for the support of Occidental minds. Many of its princi ples are culled from the Christian religion which it insidiously seeks to supplant. What this Oriental cult is, what it stands for, and what it aims at, is told in a volume which forms a notable addition to the History of Comparative Religions. Persian Life and Customs. With Incidents of Residence and Travel in the Land of the Lion and the Sun. With a map and other illustrations, and an index. 8vo, cloth, net, $1.25. "Not only a valuable contribution to the mis sionary literature of modern times, but is, in ad dition, a volume rich in the facts it contains in regard to that historic country. The American people generally should read this book, and thereby acquire much needed information about the Persians." Religious Telescope. Baha’i Faith and Its Claims A Study of the Religion Promulgated by Baha’u’llah and Abdul Baha By SAMUEL GRAHAM WILSON, D. D. Thirty-two Tears Resident in Persia Author of "Persian Life and Customs" etc. NEW YORK CHICAGO TORONTO Fleming H. Revell Company LONDON AND EDINBURGH Copyright, 1915, by FLEMING H. REVELL COMPANY New York: 158 Fifth Avenue Chicago: 125 North Wabash Ave. Toronto: 25 Richmond Street, W. -

The Qur' An's Numerical Miracle

HOAH and HEAESY BY ABU AMEENAH BILAL PHILIPS AL FURQAN PUBLICATIONS \.' THE QUR' AN'S •iA.ff J • & NUMERICAL .;,-r;wr MIRACLE: .:~.. .a.Milf HOAX.. - AND.. HERESY. ·~J j ...JII ~ by ABU AMEENAH BILAL PHILIPS R.B.# 585 AL-FURQAN PUPLICATIONS RIYADH· SAUDI ARABIA © Abu Ameenah Bilal Philips, 1987/1407 AH All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used for publication without the written permission of the copyright holder, application for which should be addres sed to the publisher. Typeset and Publishea oy: AL-FURQAN ADVERTISING AGENCY, P. 0. Box 21441, Riyadh 11475, Saudi Arabia. Tel.: 401 4671 - 402 5964 CONTENTS Foreword ................................................................. ii Introduction ........................................................... 1 1. Interpretation out of Context ............................... 6 2. Letter Count: Totals ........................................... 10 3. Letter Count: Inconsistency ................................ .. 12 4. Letter Count: Manipulation 17 5. Letter Count: Data Falsification ............................ 20 I. Additions to the Qur'an's Text 21 II. Deletions From The Qur'an's Text ............ 23 6. Word Count: Grammatical Inconsistencies .............. 25 7. Word Count: Data Falsification ............................ 29 I. Ism ...................................................... 31 II. Allah ................................................. .. 32 Rejection of a Part of the Qur'an .............. 32 Doctored Data ..................................... 39 III. Ar-Rahman -

In Their Own Words: Voices of Jihad

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as CHILD POLICY a public service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION Jump down to document ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT 6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and PUBLIC SAFETY effective solutions that address the challenges facing SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY the public and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Support RAND TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Purchase this document WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Learn more about the RAND Corporation View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND monographs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. in their own words Voices of Jihad compilation and commentary David Aaron Approved for public release; distribution unlimited C O R P O R A T I O N This book results from the RAND Corporation's continuing program of self-initiated research. -

Review of Religions Centenary Message from Hadhrat Khalifatul Masih IV

Contents November 2002, Vol.97, No.11 Centenary Message from Hadhrat Ameerul Momineen . 2 Editorial – Mansoor Shah . 3 Review of Religions: A 100 Year History of the Magazine . 7 A yearning to propogate the truth on an interntional scale. 7 Revelation concerning a great revolution in western countries . 8 A magazine for Europe and America . 9 The decision to publish the Review of Religions . 11 Ciculation of the magazine . 14 A unique sign of the holy spirit and spiritual guidance of the Messiah of the age. 14 Promised Messiah’s(as) moving message to the faithful members of the Community . 15 The First Golden Phase: January 1902-May 1908. 19 The Second Phase; May 1908-March 1914 . 28 Third Phase: March 1914-1947 . 32 The Fourth Phase: December 1951-November 1965. 46 The Fifth Phase: November 1965- June 1982 . 48 The Sixth Phase: June 1982-2002 . 48 Management and Board of Editors. 52 The Revolutionary articles by Hadhrat Mirza Tahir Ahmad. 56 Bright Future. 58 Unity v. Trinity – part II - The Divinity of Jesus (as) considered with reference to the extent of his mission - Hadhrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (as) . 60 Chief Editor and Manager Chairman of the Management Board Mansoor Ahmed Shah Naseer Ahmad Qamar Basit Ahmad. Bockarie Tommy Kallon Special contributors: All correspondence should Daud Mahmood Khan Amatul-Hadi Ahmad be forwarded directly to: Farina Qureshi Fareed Ahmad The Editor Fazal Ahmad Proof-reader: Review of Religions Shaukia Mir Fauzia Bajwa The London Mosque Mansoor Saqi Design and layout: 16 Gressenhall Road Mahmood Hanif Tanveer Khokhar London, SW18 5QL Mansoora Hyder-Muneeb United Kingdom Navida Shahid Publisher: Al Shirkatul Islamiyyah © Islamic Publications, 2002 Sarah Waseem ISSN No: 0034-6721 Saleem Ahmad Malik Distribution: Tanveer Khokhar Muhammad Hanif Views expressed in this publication are not necessarily the opinions of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community. -

Salman the Persian, Zoroastrian, Persia (Part 1 of 2): from Zoroastrianism to Christianity

Salman the Persian, Zoroastrian, Persia (part 1 of 2): From Zoroastrianism to Christianity Description: One of the greatest of companions, Salman the Persian, once Zoroastrian (Magian) narrates his story of his search for the true religion of God. Part One: From Zoroastrianism to Christianity. By Salman the Persian Published on 18 Jun 2007 - Last modified on 15 Dec 2008 Category: Articles >Stories of New Muslims > Personalities Category: Articles >The Prophet Muhammad > Stories of His Companions The blessed Companion of the Prophet Muhammad, may the mercy and blessings of God be upon him, Salman al-Farisi narrates[1] his journey to Islam as follows: "I was a Persian man from the people of Isfahaan[2] from a town known as Jayi. My father was the town chief. To him, I was the most beloved creature of God. His love for me reached the point to which he trusted me to supervise the fire[3] he lit. He would not let it die down. My father owned a large area of fertile land. One day, while busy with his construction, he told me to go to his land and fulfill some chores he desired. On my way to his land, I came across a Christian church. I heard the sound of people praying inside. I did not know how people lived outside, for my father kept me confined to his house! So when I came across those people [in the church] and I heard their voices, I went inside to watch what they were doing." When I saw them, I liked their prayers and became interested in their religion. -

Aug-Sep 1970

BISMILLA-HIR-RAHMANIR-RAHIM THE AHMADIYYA GAZETTE AUG - SEP 1970 VOL. IX - NO. 8 Li'Pb'^ (Holy Quran, 4:96; 8:73) NO organization, religious or secular, can propser without money. This is why, when Allah exhorts the believers to strive in His cause. He j •a.i. .. oarticularly to be the case in the Latter Days, this S®why^n?*Holy^Prophet, 'peace and blessings of Allah be on him said, when ^e promised Messiah comes, he will abolish physical fighting, in other wor^, l*ere would be no need of fighting physical battles for the propagation of course, "Jihad" there must be, and more intense and longer, but not with the bo y and the sworD, but with money and pen. The Promised Messiah, peace be on him, has come, and has declared war- with the forces of evil. To carry on this war he has demanded from his followers moneta^ contribution and not physical fighting. His Second Khalifa (Successor) regularizeD this contribution, and fixed it to be at least, l/16th of one's mon^ly income and further enunciated that one who does not contribute at this rate, without legitimate grounds, and securing permission to pay at a lesser rate, shall not be co^idere sincere and true Ahmadis. He further declared definitely that one who fails to pay, at this rate, without any reasonable excuse, for consecutive six months, shall not be entitled to vote or be eligible for any office of the Jamat (Comm^ity). TUimadis in Pakistan have been, by the Grace of Allah, regularly paying a is ra e, many (about twenty five thousand Ahmadis v4io are called "Musis") are paying 1/lOth and some even 1/3, and Allah, too, has been showering His Blessing upon them and increasing their income, and they, too, are giving, ever more and more. -

Mahdaviah Insight (A Publication of Mahdavia Islamic Center of Chicago )

Mahdaviah Insight (A Publication of Mahdavia Islamic Center of Chicago ) February 2017 (Rabi us-Thani/Jamadi ul Awwal, 1438 H) | Issue 20 Editorial: Perfection of Religion In the name of Allah, the Most Beneficent, the Most Merciful. Inside this issue: Allah SWT sent His Caliph, Mahdi Al-Ma’ud AS, for the guidance of humankind for propagating the teach- ings of Vilayat of Prophet Muhammad SAS in this month. The Milad of Mahdi AS will occur on 14th of Jamadi ul Awwal that corresponds to February 11 this year. Let us pray our Lord, Almighty Allah to Editorial 1 guide us and keep us firm on our faith. Our faith is more comprehensive as we not only believe in Allah SWT, His angels, the day of judgement, His books, His prophets, but also His Caliph who came after 847 years from the beginning of Islamic calendar. Advent of Mahdi 2-4 (A.S.) - A Religious We know that Prophet Muhammad SAS did not say anything on his own but whatever he said, it is the Necessity Part-II revelation (Wahi) that was sent to him by Allah SWT.As Qur’an says: “He does not speak out of his own desires. It is a revelations which has been revealed to him.”(Al-Qur’an, 53:3-4) Therefore, even a single Qur’anic verse 2 Hadith is more than enough to believe in the advent of Mahdi. However, there are people who believe that after the revelation of Qur’an and after the advent of the last prophet, Muhammad SAS, there is no need of Hadith and Naql 3 any other person to come or to be sent by Allah. -

Marshall Communicatingthewo

COMMUNICATING THE WORD Previously Published Records of Building Bridges Seminars The Road Ahead: A Christian-Muslim Dialogue, Michael Ipgrave, Editor (Church House Publishing) Scriptures in Dialogue: Christians and Muslims Studying the Bible and the Qur’a¯n Together, Michael Ipgrave, Editor (Church House Publishing) Bearing the Word: Prophecy in Biblical and Qur’a¯nic Perspective, Michael Ipgrave, Editor (Church House Publishing) Building a Better Bridge: Muslims, Christians, and the Common Good, Michael Ipgrave, Editor (Georgetown University Press) Justice and Rights: Christian and Muslim Perspectives, Michael Ipgrave, Editor (Georgetown University Press) Humanity: Texts and Contexts: Christian and Muslim Perspectives, Michael Ipgrave and David Marshall, Editors (Georgetown University Press) For more information about the Building Bridges seminars, please visit http://berkleycenter.georgetown.edu/networks/building_bridges Communicating the Word Revelation, Translation, and Interpretation in Christianity and Islam A record of the seventh Building Bridges seminar Convened by the Archbishop of Canterbury Rome, May 2008 DAVID MARSHALL, EDITOR georgetown university press Washington, DC ᭧ 2011 Georgetown University Press. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Communicating the word : revelation, translation, and interpretation in Christianity and Islam : a record of the seventh Building Bridges seminar convened by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Rome, May 2008 / David Marshall, editor. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-58901-784-9 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. -

The Muslim 500 2011

The Muslim 500 � 2011 The Muslim The 500 The Muslim 500 � 2011 The Muslim The 500 The Muslim 500The The Muslim � 2011 500———————�——————— THE 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS ———————�——————— � 2 011 � � THE 500 MOST � INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · All rights reserved. No part of this book may be repro- The Muslim 500: The 500 Most Influential Muslims duced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic 2011 (First Edition) or mechanic, inclding photocopying or recording or by any ISBN: 978-9975-428-37-2 information storage and retrieval system, without the prior · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · written permission of the publisher. Views expressed in The Muslim 500 do not necessarily re- Chief Editor: Prof. S. Abdallah Schleifer flect those of RISSC or its advisory board. Researchers: Aftab Ahmed, Samir Ahmed, Zeinab Asfour, Photo of Abdul Hakim Murad provided courtesy of Aiysha Besim Bruncaj, Sulmaan Hanif, Lamya Al-Khraisha, and Malik. Mai Al-Khraisha Image Copyrights: #29 Bazuki Muhammad / Reuters (Page Designed & typeset by: Besim Bruncaj 75); #47 Wang zhou bj / AP (Page 84) Technical consultant: Simon Hart Calligraphy and ornaments throughout the book used courtesy of Irada (http://www.IradaArts.com). Special thanks to: Dr Joseph Lumbard, Amer Hamid, Sun- dus Kelani, Mohammad Husni Naghawai, and Basim Salim. English set in Garamond Premiere -

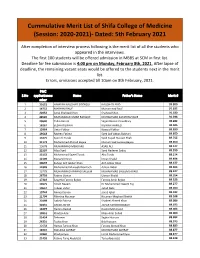

Cumulative Merit List

Cummulative Merit List of Shifa College of Medicine (Session: 2020-2021)- Dated: 5th February 2021 After completion of interview process following is the merit list of all the students who appeared in the interviews. The first 100 students will be offered admission in MBBS at SCM in first list. Deadline for fee submission is 4:00 pm on Monday, February 8th, 2021. After lapse of deadline, the remaining vacant seats would be offered to the students next in the merit list. Errors, omissions accepted till 10am on 8th February, 2021. PMC S.No applicationnu Name Father's Name Merit # mber 1 21623 HAMZAH NAUSHAD SIDDIQUI NAUSHAD ABID 93.200 2 14752 MARYAM RAUF Muhammad Rauf 91.632 3 22652 Amal Shahzad Khan Shahzad Khan 91.180 4 28526 MUHAMMAD UMAR RAFIQUE MUHAMMAD ZAFAR RAFIQUE 91.036 5 20640 Talha Rasool Sajjad Rasool Chaudhary 90.282 6 18267 EESHA RIZWAN RIZWAN AHMED 90.045 7 12964 Umar Fakhar Nawaid Fakhar 89.890 8 19618 Raveen Fatima Syed Asif Abbas Bukhari 89.850 9 13475 Syed Ali Turab Syed Sajjad Hussain Shah 89.755 10 31173 Muhammad Ahmed Bajwa Muhammad Farooq Bajwa 89.650 11 13678 MUHAMMAD MEHDI ALI ASAD ALI 89.577 12 21597 Aliza Syed Syed Nadeem Sadiq 89.559 13 15152 Muhammad Sajeel Turab Abu Turab 89.514 14 12109 Manahil Imran Imran Khalid 89.494 15 30637 Zuhayr Arif Jabbar Khan Arif Jabbar Khan 89.477 16 11849 Muhammad Muneeb Warriach Adnan Akbar 89.464 17 13779 MUHAMMAD AMMAD SALEEM MUHAMMAD SALEEM JAVAID 89.427 18 26793 Fatima Usman Usman Khalid 89.354 19 17319 Sayyeda Farooq Bajwa Farooq Amin Bajwa 89.323 20 13675 Alizeh Naeem