Ottomans-Safavids-Mughals:Shared Knowledge and Connective Systems Francis Robinson the Boundaries of Modern Nation-States An

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SHAH WALIY ALLAH ATTEMPTS to REVISE WAHDAT AL- WUJUD by ABDUL HAQ ANSARI HE Theosophical System Of

SHAH WALIY ALLAH ATTEMPTS TO REVISE WAHDAT AL- WUJUD BY ABDUL HAQ ANSARI HE theosophical system of re?ahdat al-zvujud', or ontological/ Texistential monism, which Ibn al-'Arabi (d. 638/1240) for- mulated, became very soon popular among the sufis. Some of them, however, did not agree with it, others disliked, and some even denounced it. Nevertheless, the doctrine continued to dominate sufi speculation for four hundred years till Shaykh Ahmad Sirhindi (d. 1034/1624) subjected its basic concepts as well as its moral and religious consequences to searching criticism, and came out with a parallel theosophy 2, popularly known as wahdat al-shuhud. Sirhindi said that mystical experience has three levels: One is the level of pure union which in modern terminology is called unitive experience; next is the experience of separation after union (farq bald al-j*amc) in which the mystic is one with God in one sense, and different from him in another; the final stage of the experience is that when the feeling of oneness or union completely disappears and God is perceived as transcending the world absolutely. Sirhindi said that some sufis like Al-Hallaj 3 (d. 309/922), remained at the first stage till the end of their life; others moved to the second stage, but stayed on there; only a few rose up to the third stage. He claims that Ibnul Arabi stayed on the second stage, and could not 1 There is a vast literature on wahdat al-wuj�d,but The Mystical Philosophyof Muhyi-d Din Ibnul Arabi of the late Dr. -

An Assessment on Some of the Opinions and Theological Convictions of Seyyid Burhaneddin (Rumi’S Master)

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 20, Issue 3, Ver. V1 (Mar. 2015), PP 79-86 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org An Assessment on Some of the Opinions and Theological Convictions of Seyyid Burhaneddin (Rumi’s Master) Osman Oral, PhD Assistant Professor of Kalam (Islamic Theology) Department of Basic Islamic Sciences Bozok University Faculty of TheologyYozgat, Turkey, 66000 Abstract: One of the main and the most important objectives of Kalam is to create a firm belief in people’s hearts, to keep this belief from the danger of doubts, and to effort for providing different methods and techniques in the light of the Qur'an and Sunnah in this way. The aim of Sufism is also to educate self-ego and to preserve the belief within this moral axis. Seyyid Burhaneddin Tirmidhi is an important Sufi who was born at the end of the XII century and lived in the first half of the XIII century. His significance comes from his being the first master of Rumi by teaching him theological and mystical aspect of Islam for a long time. This article examines theological opinions of Seyyid Burhaneddin who has a significant place in the Sufi circles and the Anatolian Islamic culture. Keywords: Seyyid Burhaneddin, Rumi, Sufism, Faith, Tirmidhi, Kayseri I. Introduction Science of Kalam, first of all explores the vahdâniyet among the God's essence and attributes.1 It also determines the principles of Islam about faith and actions through nass (the Qur‟an and the Sunnah) and builds them on the basis of rational method.2 Sufism brings the truths of Islamic Theology toward general issues into very simple level which let also everyone will be satisfied. -

Al-BID'ah VERSUS AL-MASHLAHAH AL

Asep Saepudin Jahar: al-Bid‘ah versus al-Mashlahah al-Mursalah and al-Istihsân 1 Al-BID‘AH VERSUS AL-MASHLAHAH AL-MURSALAH AND AL-ISTIHSÂN: AL-SYÂTHIBI’S LEGAL FRAMEWORK Asep Saepudin Jahar Graduate School Syarif Hidayatullah State Islamic University Jakarta Jl. Kertamukti, Pisangan, Ciputat Timur, Tangerang Selatan, Banten E-mail: [email protected] Abstrak: al-Bid‘ah versus al-Mashlahah al-Mursalah dan al-Istihsân: Kerangka Hukum al-Syâthibî. Tulisan ini mengkaji pandangan Abû Ishâq al-Shâthibî (w. 790/1388) tentang bidah versus al-mashlahah al-mursalah dan al-istihsân. Karya al-Syâthibî tentang konsep bidah dalam kitabnya, al-I'tishâm, sebagai respons terhadap ulama di zamannya yang menganggap bahwa al-mashlahah al-mursalah dan al-istihsân sebagai bentuk inovasi (al-bid‘ah). Tulisan ini akan mengelaborasi signifikansi gagasan al-Syâthibî dalam isu bidah yang memformulasikan kerangka syariah berbasis teks dan rasio dengan non-syariah. Pembahasan tentang bidah sebagai perbuatan yang bertentangan dengan prinsip syariah akan dianalisis dengan prinsip legalitas al-mashlahah al-mursalah dan al-istihsân sebagai bagian dari metodologi penggalian hukum setelah Alquran, Sunah, ijmak, dan qiyâs. Tulisan ini juga ingin menguraikan keunggulan al-Syâthibî dalam epistemologi hukum dibanding ulama lain yang membahas isu serupa. Kata Kunci: al-istihsân, bidah, al-mashlahah al-mursalah, faqîh, teori hukum Abstract: al-Bid‘ah versus al-Mashlahah al-Mursalah and al-Istihsân: Al-Syâthibî’s Legal Framework. This paper discusses with the juridical basis of Abû Ishâq al-Shâthibi’s (d. 790/1388) argument against those who considered al-mashlahah al-mursalah (public interest) and al-istihsân (juristic preference) to be forms of innovation. -

Mewlana Jalaluddin Rumi - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Mewlana Jalaluddin Rumi - poems - Publication Date: 2004 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Mewlana Jalaluddin Rumi(1207 - 1273) Jalal ad-Din Muhammad Balkhi (Persian: ?????????? ???? ?????), also known as Jalal ad-Din Muhammad Rumi (?????????? ???? ????), and more popularly in the English-speaking world simply as Rumi (30 September 1207 – 17 December 1273), was a 13th-century Persian[1][6] poet, jurist, theologian, and Sufi mystic.[7] Iranians, Turks, Afghans, Tajiks, and other Central Asian Muslims as well as the Muslims of South Asia have greatly appreciated his spiritual legacy in the past seven centuries.[8] Rumi's importance is considered to transcend national and ethnic borders. His poems have been widely translated into many of the world's languages and transposed into various formats. In 2007, he was described as the "most popular poet in America."[9] Rumi's works are written in Persian and his Mathnawi remains one of the purest literary glories of Persia,[10] and one of the crowning glories of the Persian language.[11] His original works are widely read today in their original language across the Persian-speaking world (Iran, Tajikistan, Afghanistan and parts of Persian speaking Central Asia).[12] Translations of his works are very popular in other countries. His poetry has influenced Persian literature as well as Urdu, Punjabi, Turkish and some other Iranian, Turkic and Indic languages written in Perso-Arabic script e.g. Pashto, Ottoman Turkish, Chagatai and Sindhi. Name Jalal ad-Din Mu?ammad Balkhi (Persian: ?????????? ???? ????? Persian pronunciation: [d?æl??læddi?n mohæmmæde bælxi?]) is also known as Jalal ad- Din Mu?ammad Rumi (?????????? ???? ???? Persian pronunciation: [d?æl??læddi?n mohæmmæde ?u?mi?]). -

An Investigation Into the Prevalence of the Hindu Yogas in Sufism

1 AN INVESTIGATION INTO THE PREVALENCE OF THE HINDU YOGAS IN SUFISM By Jalaledin Ebrahim M.A. Ph.D (c) http://jalaledin.blogspot.com Introduction With the recent proliferation of translations into English of the love poetry of Mevlana Jalaluddin Rumi and Hafez, Sufism, which is the esoteric or mystical dimension of Islam, has been widely considered, in the popular literature, a “ bhakti ” tradition, in which, “the aim of bhakti yoga is to direct toward God the love that lies at the base of every heart” (Smith, 1991, p. 32). On further investigation, a deeper appreciation of Sufism can be gained by comparing and contrasting the combinations (or lack thereof) of the Hindu yogas in the paths of several renowned Sufi Masters, such as Mansur Al- Hallaj (d. 992), Jalaluddin Rumi (d. 1273), Hafez (d. 1389), and Ibn al-Arabi (d.1240), who was known as the Shaykh al-Akbar, the greatest Sufi Master and the Seal of the Saints. 2 This paper seeks to explore the paths of these Sufi Masters within the framework of the four Hindu yogas and their relationship to the “stations of the heart” presented by a Sufi sheikh of the Jerrahi Order, Dr. Robert Frager, (1999) in “Heart, Self and Soul: The Sufi Psychology of Growth, Balance and Harmony.” Frager explains the contribution of Hakim al-Tirmidhi (d.ca. 932) to the theory of Sufism’s “four stations of the heart”: the breast, the heart, the inner heart and the innermost heart. Each of these stations houses a light. “The breast is the home of the Light of Practice of the outer forms of any religion. -

Metempsychosis (Tanasukh) in Mulla Sadra's Thought*

METEMPSYCHOSIS (TANASUKH) IN MULLA SADRA'S THOUGHT* Shigeru KAMADA** I The idea of metempsychosis (tanasukh)(1) with its complicated manifesta- tions appeared in the various aspects of Islamic thought and gave rise to heated controversies on its position in the Islamic framework among Muslim scholars. The idea can be divided into two types.(2) The first is that on its separation from a body one's soul takes a different form by its new at- tachment to another body of a higher or a lower species according to one's conduct in the life just ended. This type is found in Indian and Greek thought, which may be termed as metempsychosis in a general sense. The second is that the divine soul permeates through and indwells in all or particular existents in the physical world, which may be termed as metempsychosis in a special sense. The latter type of the metempsychosis often finds its expression in extreme Shi'te thought (ghulat) and Islamic mysticism, the manner in which it appears is that the Imam inherits a spark of the divine light (nur ilahi) through his preceding prophets or Imams from the first prophet Adam, or embodies Divinity through the incarnation (hulul) of the divine spirit in him.(3) The idea of incarnation gave birth to a series of incarnationists condemned among Islamic mystics.(4) The main purpose of this paper is to clarify Mulla Sadra's concept of metempsychosis. Mulla Sadra (d. 1050/1640) was a mystic philosopher in Safavid Iran.(5) First we would like to survey the common understanding of metempsychosis in Islam before our reading of Mulla Sadra's text. -

The Muslim 500 2011

The Muslim 500 � 2011 The Muslim The 500 The Muslim 500 � 2011 The Muslim The 500 The Muslim 500The The Muslim � 2011 500———————�——————— THE 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS ———————�——————— � 2 011 � � THE 500 MOST � INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · All rights reserved. No part of this book may be repro- The Muslim 500: The 500 Most Influential Muslims duced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic 2011 (First Edition) or mechanic, inclding photocopying or recording or by any ISBN: 978-9975-428-37-2 information storage and retrieval system, without the prior · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · written permission of the publisher. Views expressed in The Muslim 500 do not necessarily re- Chief Editor: Prof. S. Abdallah Schleifer flect those of RISSC or its advisory board. Researchers: Aftab Ahmed, Samir Ahmed, Zeinab Asfour, Photo of Abdul Hakim Murad provided courtesy of Aiysha Besim Bruncaj, Sulmaan Hanif, Lamya Al-Khraisha, and Malik. Mai Al-Khraisha Image Copyrights: #29 Bazuki Muhammad / Reuters (Page Designed & typeset by: Besim Bruncaj 75); #47 Wang zhou bj / AP (Page 84) Technical consultant: Simon Hart Calligraphy and ornaments throughout the book used courtesy of Irada (http://www.IradaArts.com). Special thanks to: Dr Joseph Lumbard, Amer Hamid, Sun- dus Kelani, Mohammad Husni Naghawai, and Basim Salim. English set in Garamond Premiere -

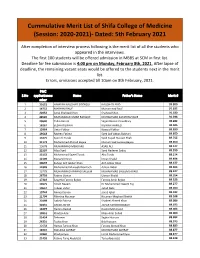

Cumulative Merit List

Cummulative Merit List of Shifa College of Medicine (Session: 2020-2021)- Dated: 5th February 2021 After completion of interview process following is the merit list of all the students who appeared in the interviews. The first 100 students will be offered admission in MBBS at SCM in first list. Deadline for fee submission is 4:00 pm on Monday, February 8th, 2021. After lapse of deadline, the remaining vacant seats would be offered to the students next in the merit list. Errors, omissions accepted till 10am on 8th February, 2021. PMC S.No applicationnu Name Father's Name Merit # mber 1 21623 HAMZAH NAUSHAD SIDDIQUI NAUSHAD ABID 93.200 2 14752 MARYAM RAUF Muhammad Rauf 91.632 3 22652 Amal Shahzad Khan Shahzad Khan 91.180 4 28526 MUHAMMAD UMAR RAFIQUE MUHAMMAD ZAFAR RAFIQUE 91.036 5 20640 Talha Rasool Sajjad Rasool Chaudhary 90.282 6 18267 EESHA RIZWAN RIZWAN AHMED 90.045 7 12964 Umar Fakhar Nawaid Fakhar 89.890 8 19618 Raveen Fatima Syed Asif Abbas Bukhari 89.850 9 13475 Syed Ali Turab Syed Sajjad Hussain Shah 89.755 10 31173 Muhammad Ahmed Bajwa Muhammad Farooq Bajwa 89.650 11 13678 MUHAMMAD MEHDI ALI ASAD ALI 89.577 12 21597 Aliza Syed Syed Nadeem Sadiq 89.559 13 15152 Muhammad Sajeel Turab Abu Turab 89.514 14 12109 Manahil Imran Imran Khalid 89.494 15 30637 Zuhayr Arif Jabbar Khan Arif Jabbar Khan 89.477 16 11849 Muhammad Muneeb Warriach Adnan Akbar 89.464 17 13779 MUHAMMAD AMMAD SALEEM MUHAMMAD SALEEM JAVAID 89.427 18 26793 Fatima Usman Usman Khalid 89.354 19 17319 Sayyeda Farooq Bajwa Farooq Amin Bajwa 89.323 20 13675 Alizeh Naeem -

The Concept of Generosity in Rumi's Mathnawi: an Analysis

THE CONCEPT OF GENEROSITY IN RUMI’S MATHNAWI: AN ANALYSIS BY SUZANA SUHAILAWATY MD. SIDEK A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Islamic and Other Civilization) International Institute of Islamic Thought and Civilization International Islamic University Malaysia JULY 2015 ABSTRACT This work examines generosity in the Mathnawi of Maulana Rumi. The thesis identifies fifteen stories not related directly to generosity in the Mathnawi. These were categorized into three groups: acts which are devoid of any generosity, sincere generosity, insincere generosity. These are mainly stories involving companions, saints and sometimes fables. The stories pertaining to the Prophet were used differently by Rumi. In some instances, he changed the gender of the person from that in the hadith and embellishes the stories with his own story. There are instances in which he takes two separate hadiths and make them one. In all cases, Rumi changes the scenario to make his own. The extensive change to the original does not allow us to call them hadith anymore. This dissertation shows that Rumi has spared no opportunity to show that generosity is extremely important in all its form and without being generous, one cannot reach the highest station in life. This is because the thesis shows that in Islam it does not only involve giving, but giving the best we have. ii ملخص البحث يقدم هذا البحث دراسة ملوضوع الكرم يف مثنوي موﻻنا جﻻل الدين الرومي. البحث يتناول مخسة عشر قصة من املثنوي ﻻ ترتبط بالكرم بشكل مباشر. مت تقسيم هذه القصص يف ثﻻث جمموعات: اﻷفعال اليت ختلو من الكرم، والكرم بإخﻻص والكرم بغري إخﻻص. -

Reinterpretation of Tarekat and the Teachings of Sufism According to Said Nursi

Millah: Jurnal Studi Agama Vol. 20, No. 2 (2021), pp 355-384 ISSN: 2527-922X (e); 1412-0992 (p) DOI: 10.20885/millah.vol20.iss2.art7 Reinterpretation of Tarekat and the Teachings of Sufism According to Said Nursi Cemal Sahin Hayrat Fondation, Istanbul, Turkey [email protected] Zaimul Asroor Universitas Islam Negeri Syarif Hidayatullah, Jakarta, Indonesia [email protected] Abstract In this modern-contemporary era, Muslims are often faced with the question, “Is it necessary to follow the teachings of the tarekat? Didn’t the tarekat (especially after al-Ghazali criticized the philosophical tradition) cause Muslims to decline and lose their critical power?” Moreover, some sufism teachings such as wahdatul wujud, wahdatus syuhud etc. Often considered as deviating from the pure teachings of Islam, especially by the Wahabi group. In order to answer some of these questions, the writer tries to present how Said Nursi responds in the interpretation of Risalah Nur. Nursi said that, "The present time is not the time of the tarekat." If it is not understood comprehensively, it will cause the reader to be inaccurate in concluding that generally Nursi rejects tarekat and some sufism teachings. That is why the writer wants to present which side of the teachings of tarekat and sufism that Nursi criticizes and what is his new offer. The research method that the author uses is library research with a socio-historical and descriptive-analysis approach using Risalah Nur as the primary source and several supporting books that are still related to the theme as a secondary source. The writer finds Millah Vol. -

Heralding a New Enlightenment

Conceptualizing the development of personality in children: An analysis of Islamic philosophy and contemporary Western psychology Muhammad Tahir and Stephan Larmar* Abstract: The paper aims to examine the concept of child personality development from the perspectives of Islamic philosophy and contemporary Western psychology. In recent decades, the parental journey associated with the healthy development of children has become increasingly complex and sometimes stressful across all societies and communities of the world. Major world religions and social sciences delineated various aspects and perspectives relating to sound personality development in children. The present article seeks to present the findings of a study that found to give an overview of fundamental principles related to child personality development drawn from Islamic philosophy and contemporary Western psychology. Drawing on these two perspectives, the paper seeks to explain personality development, highlighting both similarities and differences associated with these perspectives. The study employed qualitative content analysis to explore relevant data from the Qur’anic verses and Prophetic traditions, as well as theoretical studies and empirical research of psychology. The research findings predominantly highlight an integrated approach towards child personality development as framed within the perspective of Islamic philosophy and contemporary Western psychological understandings. The paper serves to link Islamic thought to contemporary Western psychological aspects -

Experiencing Rumi and Pico

EXPERIENCING RUMI AND PICO: CONVERGING THOUGHTS, DIVERGING KNOWLEDGE A Thesis submitted to the faculty of AS 36 San Francisco State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for • SU the Degree Master of Arts In Humanities by Parisa Soultani Sausalito, California December 2017 Copyright by Parisa Soultani 2017 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read Experiencing Rumi and Pico: Converging Thoughts, Diverging Knowledge by Parisa Soultani, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Master of Arts in Humanities at San Francisco State University. Carel Bertram Ph.D. Professor of Humanities <x_ Sandra Luft Ph.D. Professor of Philosophy EXPERIENCING RUMI AND PICO: CONVERGING THOUGHTS, DIVERGING KNOWLEDGE Parisa Soultani Sausalito, California 2017 Giovanni Pico della Mirandola (1463-1494) and Jalal ad-Din Muhammad Rumi (1207- 1273) came to similar conclusions while looking for answers to deep questions about the place of human in nature and her relationship to God. Both Rumi and Pico sought to approach this quest with an open mind that uses reason and experience rather than relying solely on traditional knowledge and religious doctrines, and they came to similar conclusions that put human concerns first in divine creation. While Pico remains reliant on reason and speaks in terms of philosophy, Rumi sees and speaks from another dimension: the path of direct experience expressed through poetry and allegory. I certify that the Abstract is a correct representation of the content of this thesis. Chair, Thesis Committee Date TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.