I Can Afford Only One Saw Right Now—So Which One Should I Buy, and What the Heck Is Your Hybrid-Cut

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New DEWALT® 20V MAX* 1/2" Mid-Range Impact Wrench

Nov 01, 2017 12:35 EDT New DEWALT® 20V MAX* 1/2" Mid- Range Impact Wrench TOWSON, MD (November 1, 2017) – DEWALT announces two new 20V MAX* 1/2" Mid-Range Impact Wrenches (DCF894 and DCF894H). They are available in detent pin style for users who need maximum socket retention and hog ring style, for users who value quickly being able to change sockets. Each tool is ideal for use overhead or when space is constrained in applications that require high torque including plumbing, mechanical, concrete and masonry, automotive, steel erection, and elevator repair. At 3.48 lbs. (tool only) and 6.95" to the front of the anvil, the 20V MAX* 1/2" Mid-Range Impact Wrenches are compact yet deliver high-power and torque. Each tool achieves 330 ft.-lbs. of maximum torque, 0-3,100 impacts per minute, and no-load speeds from 0-900 and 0-2,000 RPM in two mode settings (low and high) designed for use in a wide variety of applications. These applications include threaded couplings, pipe flanges, wheel lugs, and concrete anchor setting, among others. The 20V MAX* 1/2" Mid-Range Impact Wrenches also features Precision Wrench™ Control which helps sense when a bolt is getting tight and pauses before impacting to help avoid over-torque. In reverse, Precision Wrench™ Control regulates how quickly a nut or bolt is removed, helping to prevent run-off. With an efficient brushless motor that provides increased efficiency and runtime over brushed units, the tool is a powerful cordless option. In addition, the Mid-Range Impact Wrench includes a variable speed trigger and LED light to help provide visibility in low light situations. -

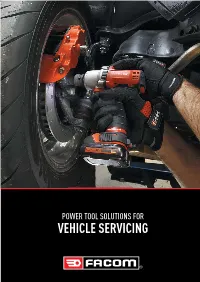

POWER TOOL SOLUTIONS for VEHICLE SERVICING Your Complete Tool Solution

POWER TOOL SOLUTIONS FOR VEHICLE SERVICING YOUR COMPLETE TOOL SOLUTION 95 YEARS 95 YEARS OF DESIGN OF INNOVATION & MANUFACTURE From the beginning FACOM’s goal has been to listen to professionals to allow us to produce tools for them FACOM is internationally recognized as one of the best that would exceed their exacting requirements, while design and manufacturing brand in the industry. incorporating features that would make everyday tasks We manufacture to the highest quality standards and easier and safer. This fundamental philosophy is very design truly innovative professional hand and power much the driving force behind the Facom brand. tools for use across the world. Today, FACOM is Europe’s leading hand tool brand with This commitment is clearly evident by the number a range of over 9,000 products, including storage of personnel employed in our design teams, with over (trolleys, cabinets, benches, portable storage), standard 250 R&D engineers operating in 10 separate offices tools (wrenches, screwdrivers, pliers, hammers, air tools) dedicated to Facom product development. FACOM and specialist tools (automotive, electrical, aerospace) translates this R&D effort into efficient, high-quality to meet the needs of all professional tool users. products manufactured within 12 factories across Europe. 2 YOUR COMPLETE TOOL SOLUTION www.facom.com 3 IN-HOUSE POWER TOOL DESIGN LEADING PRODUCTS DEWALT® BATTERY PLUS A GREAT RANGE SWAP With over 95 years of automotive and industrial experience FACOM has developed a comprehensive power tools range to meet a vast range of job requirements, including: Our cordless tools now use the new premium lithium-ion battery platform. -

1. Hand Tools 3. Related Tools 4. Chisels 5. Hammer 6. Saw Terminology 7. Pliers Introduction

1 1. Hand Tools 2. Types 2.1 Hand tools 2.2 Hammer Drill 2.3 Rotary hammer drill 2.4 Cordless drills 2.5 Drill press 2.6 Geared head drill 2.7 Radial arm drill 2.8 Mill drill 3. Related tools 4. Chisels 4.1. Types 4.1.1 Woodworking chisels 4.1.1.1 Lathe tools 4.2 Metalworking chisels 4.2.1 Cold chisel 4.2.2 Hardy chisel 4.3 Stone chisels 4.4 Masonry chisels 4.4.1 Joint chisel 5. Hammer 5.1 Basic design and variations 5.2 The physics of hammering 5.2.1 Hammer as a force amplifier 5.2.2 Effect of the head's mass 5.2.3 Effect of the handle 5.3 War hammers 5.4 Symbolic hammers 6. Saw terminology 6.1 Types of saws 6.1.1 Hand saws 6.1.2. Back saws 6.1.3 Mechanically powered saws 6.1.4. Circular blade saws 6.1.5. Reciprocating blade saws 6.1.6..Continuous band 6.2. Types of saw blades and the cuts they make 6.3. Materials used for saws 7. Pliers Introduction 7.1. Design 7.2.Common types 7.2.1 Gripping pliers (used to improve grip) 7.2 2.Cutting pliers (used to sever or pinch off) 2 7.2.3 Crimping pliers 7.2.4 Rotational pliers 8. Common wrenches / spanners 8.1 Other general wrenches / spanners 8.2. Spe cialized wrenches / spanners 8.3. Spanners in popular culture 9. Hacksaw, surface plate, surface gauge, , vee-block, files 10. -

Principles of Hand Tool Selection

Loss Prevention Reference Note Principles of Hand Tool Selection Repetitive use of manual This reference note gives some of the ergo- or powered hand tools is often nomic principles that can help guide you in a factor in carpal tunnel syn- selecting the proper manual or powered hand drome and other hand and wrist tools for repetitive tasks. disorders. While most tools are General Principles satisfactory for general purpose use, they may be entirely inappropriate for con- Before selecting any tool, you should first tinual or repetitive use in a production situation. ensure that the work area is ergonomically sound in For instance, a 15-pound hand tool may be per- terms of work surface height, adjustable seating, fectly acceptable for occasional use,1 but tools that acceptable manual handling requirements, etc. (See are used frequently or repetitively should weigh no LP 185, “Ergonomic Recommendations for Work- more than 4 pounds (1.75 kg).2 In addition, the place Design.”) Tilting the work surface or using working environment as a whole may also have fixtures to hold, tilt, or rotate the work can help to be evaluated and corrected. A properly designed minimize awkward wrist motions and simplify hand tool used in an awkward posture will not tool selection. solve the problem. Powered hand tools, rather than manual, Hand tools vary con- Characteristics to Avoid should be used whenever siderably in shape, size, When Selecting Hand Tools possible, because re- and weight. The way a peated manual exertion tool is designed influ- ■ Sharp edges and corners on tool handles. is more likely to cause ences the hand positions ■ Narrow handles, which concentrate large discomfort and injury. -

Essential Tools for Contractors

2016 CONTRACTOR RESOURCE ESSENTIAL PRODUCTS FOR CONTRACTORS Insulated Tools Holemaking Test & Measurement Safety Equipment Cable & Bolt Cutters Wire Pulling & Conduit Tools Power Tool Accessories Work @ Height Pliers Torque Wrenches / Screwdrivers These days, it can be hard to find companies that make TABLE OF CONTENTS products you can count on. But that’s exactly what you’ll get from Pliers with Tether Ring 1 Klein Tools. We don’t just make great products, we make great products Fish Tapes, Lubricants & Accessories 2 that stand up to the demands of the Conduit Benders, Fish Rods & Accessories professionals who use them every day. 3 Because our standards are as high as Low Voltage Wire Pulling yours, we demand that every product we 4 offer delivers all the performance, Holemaking 5 durability and precision that you need to get the job done right. Test & Measurement and Accessories 6-7 And by using only the highest quality Electrical Testers materials, superior workmanship, and 8 keeping our manufacturing as close to Torque Tools 9 home as we can, we’re able uphold those rigorous standards. Power Tool Accessories 10-11 Klein isn’t just the name of our company, Personal Protective Safety Equipment / Gloves it’s also our family name, so we have to 12-14 be proud of everything we make. And Insulated Tools 15-16 since we’re an American company that’s been family-owned and family-run, since Cable Cutters 17 1857, you know you can count on us to be here tomorrow. Bolt Cutters 18 So buy a Klein tool and you’ll know what Reference Guide 19-20 all the professionals know…when you pick up a Klein, it’ll never let you down. -

Product Index Product Index

Product Index Klein Pliers ........ Pages 5–23 Wrenches ............Pages 103–118 Journeyman Hex-Key TM Series ...............Pages 24–28 Wrenches ............Pages 119–128 Telecom/ Levels & Index Product Datacom Tools .......Pages 29–32 Measuring Tools .....Pages 129–134 Voice-Data- Fish Tapes & Video Tools ..........Pages 33–42 Conduit Tools ........Pages 135–146 6 Strippers, Personal Protection 6 Cutters & Equipment & Crimpers .............Pages 43–50 Safety Products ......Pages 147–156 W E A R E Y E P R OTECTI O N M Tool Pouches, Cable & Belts, Carriers, Bolt Cutters. .Pages 51–58 & Suspenders ........Pages 157–175 D W 2 E 1 A 3 R Y - 9 E N N S Y E N N PROTECTIO Insulated Tools ......Pages 59–70 Tool Bags ............Pages 176–185 Screwdrivers, Nut Drivers Tool Storage .........Pages 186–191 & Accessories ........Pages 71–102 15_Tool_Storage 15_Tool_Storage 1 Please visit www.kleintools.com for downloadable color product images and PDF formatted Klein Tools Catalogs. Product Index Lineman Buckets Knives & & Accessories ........Pages 192–197 Cutting Tools ........Pages 283–291 Hammers, Chisels Block & Tackle ..... Pages 198–202 & Punches ...........Pages 292–295 Wire Pulling CL200 Test & AUTO A Grips .................Pages 203–230 AC Measurement ........Pages 296–312 Steel Construction Flashlights ...........Pages 313–316 Product Index Product Tools .................Pages 231–234 Mining & Heavy Industry Hand Cleaners .......Pages 317–318 Tools .................Pages 235–256 HVAC19a_Mining-Tools Sheet Metal Tools/HVAC ..........Pages 257–265 Tool Sets .............Pages 319–325 Holemaking Indexes ..............Pages 326–336 Products & Accessories ..........Pages 266–278 Q U CI K U . S TA R S A. T Cat. No. 1032C CARBON S HARD TE ETH-FLE TEEL X. -

Hand Tool Safety

Safety Talk Hand Tool Safety Before you begin The greatest hazards posed by hand tools result from misuse and improper maintenance. Review the history of hand tool incidents in your organization and the action plans designed to correct or avoid future possible incidents. Introduction One of the key issues associated with hand tool safety is choosing and using the right tool. Unfortunately, many people use tools improperly at home, where they improvise with what they have on hand. Also, many people view hand tools as simple to use, so there is little concern for safety. In reality, a person using hand tools, no matter what they are, should always follow safety precautions and the manufacturer’s instructions. Injuries range from simple cuts, contusions, and abrasions to amputations, fractures, and punctures. The fact that nearly everyone uses hand tools in some fashion further complicates the education process. By looking at the injury statistics for your organization, you can discover valuable clues about the tools workers are misusing most often. June 2020 Perform a survey of your organization’s hand tools. Locate a representative sample of the tools for the pre- sentation. Become familiar with your organization’s injury experience and know the proper way to use, inspect and store those tools. Typical hand tools workers use in your organization could include hammers, saws, pliers, wrenches, screwdrivers, and knives. Below are examples of improper use of hand tools. • Pushing rather than pulling a wrench to loosen a tight fastener. • Bending metal with undersized pliers, which can damage the pliers and the metal. -

DEWALT® Launches Cordless Brushless Grinders

Sep 28, 2017 16:32 EDT DEWALT® Launches Cordless Brushless Grinders TOWSON, MD - (September 28, 2017) – DEWALT® announces the launch of cordless brushless grinders, including the 20V MAX* XR® 4.5” Angle Grinder (DCG413R2), the 20V MAX* XR® 5” Flathead Grinder (DCG413FR2), and the 20V MAX* XR® 1-1/2” Die Grinder (DCG426M2). The new cordless grinders feature efficient, brushless motors that are durable, don’t require brush changes, and offer long runtime. The new 20V MAX XR® Angle Grinder (DCG413R2) from DEWALT features a brake, E-Clutch® System, and Kickback Brake. The brake quickly brings the wheel to a stop in two seconds or less when the trigger is released. The E- Clutch® System automatically shuts down the motor when a wheel pinch is detected. The Kickback Brake incorporates both of these features, activating in the event that a pinch or stall occurs, engaging the brake at maximum force and shutting the tool down; effectively reducing the force towards the user. Additionally, the grinder features a One-Touch™ Guard, which allows for single-action adjustments to change guard position. The grinder also comes with two removable mesh screens that help to block debris from entering the tool during use. Finally, the grinder features an on/off trigger switch that has a no-volt release function, to stop accidental turn-on. In the event of a power outage or other unexpected shut down, the trigger switch will need to be cycled (turned off and then on) to restart tool. At only 3.75 lbs. (tool only) and 12.2" long, the tool achieves up to 850 MWO and is part of the 20V MAX* system of tools. -

Hand Tool Identification

HAND TOOL IDENTIFICATION Left click or use the Roller on the mouse to navigate To help protect your privacy, PowerPoint prevented this external picture from being automatically downloaded. To download and display this picture, click Options in the Message Bar, and then click Enable external content. MEASURING TOOLS BENCH RULE TAPE MEASURE FOLDING EXTENTION LASER STEEL LONG TAPE RULE To help protect your privacy, PowerPoint prevented this external picture from being automatically downloaded. To download and display this picture, click Options in the Message Bar, and then click Enable external content. SAWS HACK SAW COPING SAW BACK SAW RIP SAW CROSSCUT SAW To help protect your privacy, PowerPoint prevented this external picture from being automatically downloaded. To download and display this picture, click Options in the Message Bar, and then click Enable external content. LAYOUT TOOLS T-BEVEL SPEED SQUARE TRY SQUARE FRAMING SQUARE COMBINATION SQUARE To help protect your privacy, PowerPoint prevented this external picture from being automatically downloaded. To download and display this picture, click Options in the Message Bar, and then click Enable external content. LAYOUT TOOLS CONTOUR GAUGE INSIDE CALIPERS OUTSIDE CALIPERS CHALK LINE PLUM BOB To help protect your privacy, PowerPoint prevented this external picture from being automatically downloaded. To download and display this picture, click Options in the Message Bar, and then click Enable external content. LEVELS LINE LEVEL TORPEDO LEVEL CARPENTERS, SPIRIT LEVEL LEVELS TRANSIT BUILDERS BUILDERS LEVEL, LEVEL TRIPOD, ROD PLANES BLOCK PLANE JACK PLANE SURFORM FASTENING TOOLS PHILLIPS SCRATCH AWL SCREWDRIVER EXTENSION PHILLIPS BIT TORQ BIT STANDARD SCREWDRIVER SQUARE BIT To help protect your privacy, PowerPoint prevented this external picture from being automatically downloaded. -

HAND TOOL IDENTFICATION Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification

Technology Engineering I & II HAND TOOL IDENTFICATION Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification An Auger bit is used to bore holes into soft materials such as wood. Can also be used with a hand drill or brace. Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Combination wrench is also known as a box end-open end wrench. Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand Tool Identification Hand -

Channellock Inc. Introduces New Xtra Slim Jaw Adjustable Wrenches

Contact: Lynn Snyder, Channellock Inc. Communications and Training Manager 814.337.9229 [email protected] Brian Hoyt, SBC Advertising 614.255.3258 [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CHANNELLOCK INC. INTRODUCES NEW XTRA SLIM JAW ADJUSTABLE WRENCHES MEADVILLE, Pa. (April 7, 2015) – Channellock Inc., a family- owned and -operated plier and hand tool manufacturer, proudly introduces a brand new line of Xtra Slim Jaw adjustable wrenches, manufactured exclusively for Channellock. The line features two different wrench sizes and a variety of features to help the professional or serious DIYer get the job done. Highlights of this new line include: 6” and 8” wrench sizes Xtra Slim Jaws are 40 percent thinner than a regular wrench of the same size Xtra Slim 3/16” jaws for extra reach and maximum accessibility Up to 20 percent greater jaw capacity – supporting larger nuts and bolts Super-wide opening that allows users to tackle big jobs with a compact wrench Four-thread knurl and non-protruding jaws provide greater capacity for improved performance in confined areas Signature CODE BLUE® grips designed for durability and comfort Properly balanced to avoid weak points in the wrench Jaws imprinted with standard and metric measurement scales “The introduction of our new Xtra Slim Jaw adjustable wrenches brings new features and a new level of versatility to an already outstanding assortment of wrenches,” said Ryan DeArment, vice president of sales and marketing. “We design all of our tools with tradesmen, professionals and serious DIYers in mind. The innovative design of these wrenches offers extra reach and versatility without sacrificing the quality and reliability that CHANNELLOCK is known for.” For more information, visit www.channellock.com. -

IRWIN INDUSTRIAL TOOL COMPANY V. US

United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit ______________________ IRWIN INDUSTRIAL TOOL COMPANY, Plaintiff-Appellee v. UNITED STATES, Defendant-Appellant ______________________ 2018-1215 ______________________ Appeal from the United States Court of International Trade in No. 1:14-cv-00285-CRK, Judge Claire R. Kelly. ______________________ Decided: April 9, 2019 ______________________ FRANCES PIERSON HADFIELD, Crowell & Moring, LLP, New York, NY, argued for plaintiff-appellee. Also repre- sented by DANIEL CANNISTRA, Washington, DC. MATTHEW JAMES GLOVER, Commercial Litigation Branch, Civil Division, United States Department of Jus- tice, Washington, DC, argued for defendant-appellant. Also represented by JEANNE DAVIDSON, JOSEPH H. HUNT; AMY RUBIN, GUY EDDON, New York, NY; MICHAEL W. HEYDRICH, Office of the Assistant Chief Counsel, United States Bureau of Customs and Border Protection, United States Department of Homeland Security, New York, NY. ______________________ 2 IRWIN INDUSTRIAL TOOL COMPANY v. UNITED STATES Before LOURIE, MAYER, and REYNA, Circuit Judges. LOURIE, Circuit Judge. The United States appeals from the judgment of the United States Court of International Trade (“the Trade Court”) granting Irwin Industrial Tool Company’s (“Irwin”) motion for summary judgment that its imported hand tools are properly classified as pliers, Irwin Indus. Tool Co. v. United States, 269 F. Supp. 3d 1294 (Ct. Int’l Trade 2017) (“Irwin II”), and interpreting subheading 8204.12.00 and 8203.20.6030 of the Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (“HTSUS”), Irwin Indus. Tool Co. v. United States, 222 F. Supp. 3d 1210 (Ct. Int’l Trade 2017) (“Irwin I”). Because the imported articles are properly classified as pliers under 8203.20.6030, we affirm.