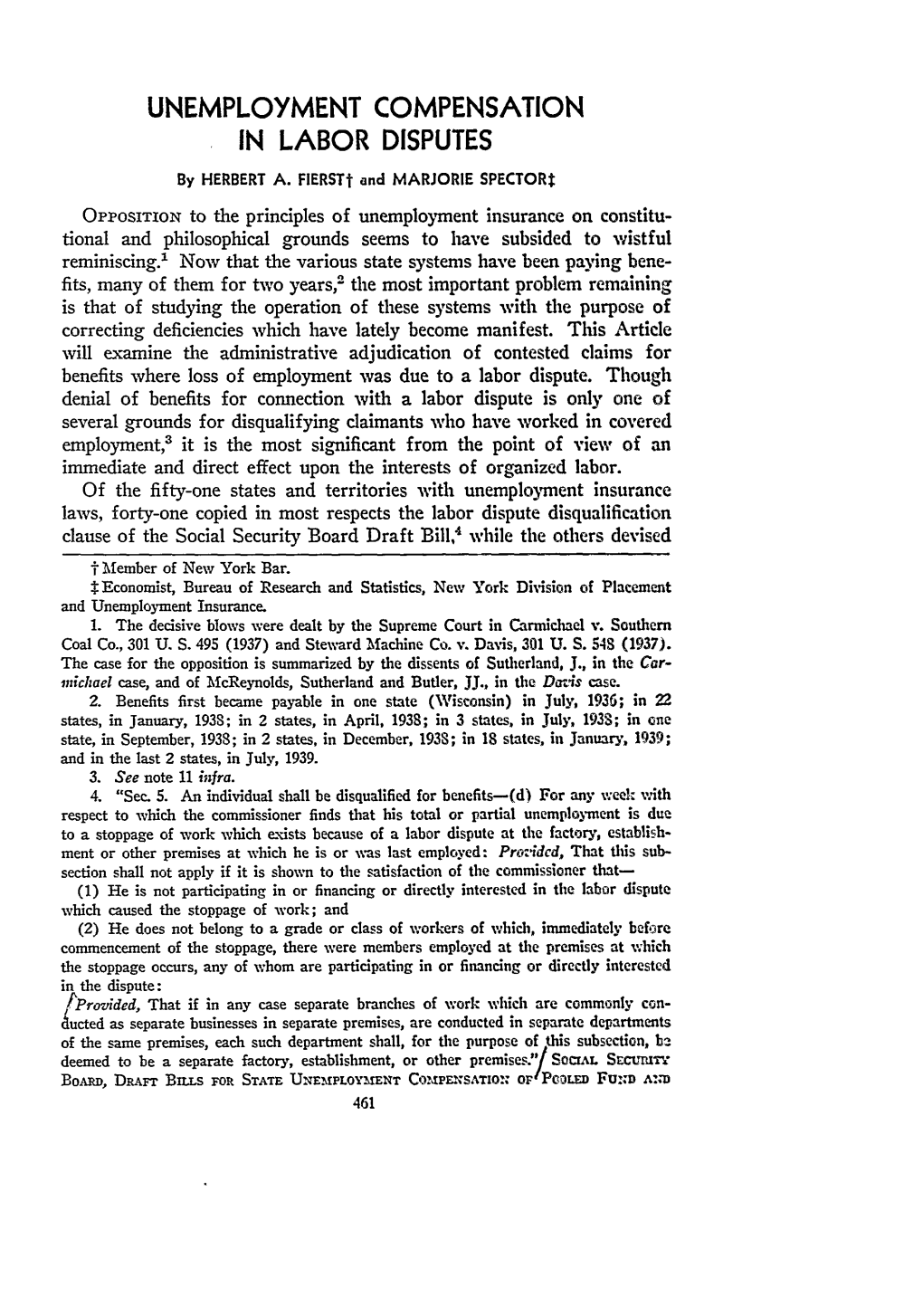

UNEMPLOYMENT COMPENSATION in LABOR DISPUTES by HERBERT A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newsupdate ® March 2017 | Volume 13, Issue 3

NEWSUPDATE ® MARCH 2017 | VOLUME 13, ISSUE 3 CORPORATE STRATEGY UPDATE 2017 EMPLOYEE SERVICE AWARD PROGRAM Faith’s current service award program was implemented in 2005, and has experienced very few changes since then. Employees who reach milestone anniversaries receive a letter, a company store voucher, a service award certificate, and a service plaque for office employees or company-branded tool for field employees. As we reviewed this well-intended employee recognition program, we began to recognize some opportunities to streamline the process to enhance our employees’ experience. For example, under today’s program, the recognized employees must personally redeem their company store voucher in order to receive a gift, and as a result, many go unused. Additionally, field employees who do redeem their coupon code, receive their anniversary gift in three separate mailings, which is cumbersome, and adds to mailing costs. In addition, the current program does not align with Faith’s current brand or core values. For these reasons, the HR and Marketing teams jointly initiated a service award program review project in fall of 2016. The revised service award recognition program provides a simplified program, accurately reflects Faith’s brand, aligns to our core values, supports Faith’s Wildly Important Goals (WIGs) established in 2016, and most importantly, places a greater emphasis on rewarding and recognizing employees as they achieve their milestone anniversary with Faith. Beginning with the first quarterly distribution in April, employees celebrating milestone anniversaries will receive: • Personal letter from Mike • Company-branded certificate highlighting their years of service • A monetary gift that will be direct deposited into their bank account on file • Follow up message on the paystub site to congratulate and thank the employee, while also reminding them of the direct deposit Similar to the current program, the gift value adjusts based on years of service. -

Employee-Handbook-082018.Pdf

Jersey Mike’s Manchester, CT Team Jersey Mike’s Manchester, CT | Employee Handbook 0 Our Core Values: Our Company Store Team mission is to be the best that we can be through giving, having fun, working hard, bettering ourselves, our team members and in return, being profitable. It is your responsibility to exemplify these core values and teach all of our employees their importance. ● Give: “Give of yourselves to others” Peter Cancro. Give your best to your co workers, our - - vendors, and our community. Our company mission is “Giving…Making a Difference in Someone’s Life”. As a member of our team, we want you to make a difference in peoples’ lives not just by providing them great experiences from behind the line but also in the community you serve. ● Have Fun: We are looking for team members who are outgoing and friendly. Bring your best attitudes to work each day. If we have fun, we will be able to work hard. ● Work Hard: Always be on time, follow up on your responsibilities, and give everything that you have. Each and every task you undertake is essential to providing distinctive quality and superior customer service. ● Better Yourself: Set goals for yourself and do what is necessary to achieve those goals. Acknowledge both your strengths and your weaknesses and commit to being more than an employee. Take ownership in your actions and be positive when wearing our uniform. “I believe that being positive not only makes me better, it makes everyone around me better.” The Positive Pledge - ● Be Profitable: The success of our business is reliant on you. -

VCCI Guide for Trainersv2

Preventing forced labour in the textile and garment supply chains in Viet Nam Guide for trainers Preventing forced labour in the textile and garment supply chains in Viet Nam Guide for trainers Copyright © International Labour Organization and Viet Nam Chamber of Commerce and Industry 2016 First published 2016 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to ILO Publications (Rights and Licensing), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered with a reproduction rights organization may make copies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro.org to find the reproduction rights organization in your country. Preventing forced labour in the textile and garment supply chains in Viet Nam : guide for trainers/ International Labour Organization and Viet Nam Chamber of Commerce and Industry. – Hanoi : ILO and VCCI, 2016 ISBN: 9789221307495; 9789221307501 (web pdf) International Labour Organization ; Viet Nam Chamber of Commerce and Industry forced labour / clothing industry / value chains / employer / trainers manual / Viet Nam 13.01.2 Also available in Vietnamese: Phòng ngừa lao động cưỡng bức -

Tennessee Civil War Trails Program 213 Newly Interpreted Marker

Tennessee Civil War Trails Program 213 Newly Interpreted Markers Installed as of 6/9/11 Note: Some sites include multiple markers. BENTON COUNTY Fighting on the Tennessee River: located at Birdsong Marina, 225 Marina Rd., Hwy 191 N., Camden, TN 38327. During the Civil War, several engagements occurred along the strategically important Tennessee River within about five miles of here. In each case, cavalrymen engaged naval forces. On April 26, 1863, near the mouth of the Duck River east of here, Confederate Maj. Robert M. White’s 6th Texas Rangers and its four-gun battery attacked a Union flotilla from the riverbank. The gunboats Autocrat, Diana, and Adams and several transports came under heavy fire. When the vessels drove the Confederate cannons out of range with small-arms and artillery fire, Union Gen. Alfred W. Ellet ordered the gunboats to land their forces; signalmen on the exposed decks “wig-wagged” the orders with flags. BLOUNT COUNTY Maryville During the Civil War: located at 301 McGee Street, Maryville, TN 37801. During the antebellum period, Blount County supported abolitionism. In 1822, local Quakers and other residents formed an abolitionist society, and in the decades following, local clergymen preached against the evils of slavery. When the county considered secession in 1861, residents voted to remain with the Union, 1,766 to 414. Fighting directly touched Maryville, the county seat, in August 1864. Confederate Gen. Joseph Wheeler’s cavalrymen attacked a small detachment of the 2nd Tennessee Infantry (U.S.) under Lt. James M. Dorton at the courthouse. The Underground Railroad: located at 503 West Hill Ave., Friendsville, TN 37737. -

Code of Conduct

CODE OF CONDUCT LIVING OUR • DEVELOPS TRUST AND RESPECT • BUILDS TEAMS AND PARTNERSHIPS • DRIVES RESULTS A MESSAGE FROM OUR PRESIDENT, CEO AND CHAIRMAN………………………………………………………………………2 PRACTICING OUR CORE VALUES.……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..3 What Are Our Core Values Open Door Policy Integrity Hotline YOU’RE PROTECTED: ANTI-RETALIATION………………………………………………………………………………………………..4 Burlington’s Response to Your Reports of Code Violations ANTI-DISCRIMINATION AND HARASSMENT POLICY…………………………………………………………………………………5 SAFE AND HEALTHY WORKPLACE…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….6 Drug and Alcohol Policy Preventing Workplace Violence Health and Safety Laws and Policies Wage and Hour Rules COMPANY RESOURCES……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………7 Use of Burlington Resources What is Private? ACCURATE RECORDS……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….8 Retaining Records Confidentiality CONFLICTS OF INTEREST …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………9 CORPORATE OPPORTUNITIES…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………10 Relatives and Personal Relationships Working Outside of Burlington & Serving on Boards GIFTS AND ENTERTAINMENT………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….12 INTEGRITY………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………14 Maintaining Integrity with Our Customers, Vendors, and Competitors CORPORATE CITIZENSHIP…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….….15 Antitrust Foreign Corrupt Practices Act /Domestic Bribery Data Security and Protection of Personal Information Product Safety INSIDER TRADING & INSIDE INFORMATION…………………………………………………………………………………………….16 -

Threat Assessment and Proactive Case Identification - a Team Approach

Threat Assessment and Proactive Case Identification - A Team Approach Sean Tepfer, National Program Manager DOJ Human Trafficking Prosecution Unit What do traffickers like? Traditional Case Identification • Local law enforcement response • Traffic stop • Response to incident or call • Investigation of other offenses • Victim outcry, 911 call • First responders • Faith-based organizations, community organizations, crime victim advocates Develop Proactive Strategies Develop Prioritize targets Conduct Threat Proactive and launch Assessment Strategies tied to Proactive Assessment Investigation Human Trafficking Task Force Training Month 20XX 4 Sex Trafficking Commercial Sex Sex Trafficking Sex Trafficking Under 18 Force, Fraud, or Coercion Pimp Controlled 6 Internet Based 7 Establishment Based Establishment Based Substance abuse controlled Transnational Sex Trafficking Gather Data and form Intelligence Sources of Tips and Leads •Community complaints •DCFS/CPS referrals •Other law enforcement •National and other hotlines •NCMEC •Others? Data from these sources • Locations • Web sites • Names • Phone numbers • License plate numbers • Involved businesses • Others? Hotline tip example No more Backpage? Deconflict •Pick up the phone •Spotlight notes •RISS – ROCIC •Innocence Lost Database •Others? Connect the dots Build Profiles • RMS • External RMS • State/Federal Probation Parole Supervision System • N-DEX via LEEP • CLEAR, Accurint, etc. • LPRs • Criminal History • Sex Offender Databases • Juvenile Probation • Child Protection Data • Social Media -

Effects of Unemployment on Child Welfare

U. S. DEPARTMENTOF LABOR JAMES J, DAVIS, Seaetery CHILDREN'SBUREAU GRACE ABBOTT. Chief UNEMPLOYMENTANDCHILD WELFARE A STUDY MADE IN A MIDDLLWESTERNAND AN EASTERNCITY DURINGTHE INDUSTRIAL DEPRESSIONOF I92I AND 1922 By EMMA OCTAVIA LUNDBERG I BueauPublication No, | 25 WASHINGTON GOVERNMET.IT PRINTING OFFICE 1923 Provided by the Maternal and Child Health Library, Georgetown University I OWINC TO LIUITED I,PPNOPRIATIOI$} TOB PBINTINC. IT IS NOT POSSIBLD TO DIIYTRTBUTE TE]S BWLETTN ,N Ir'\&GE QUANTITIES. ADDIfiONAL COPIES

Tracy City, TN)

New Light on Skirmish Here (Tracy City, TN) By JIM NICHOLSON (Since interest has grown lately in the Civil War between the United States of America, I felt it would be of help to researchers of said War if I transcribed the series of newspaper articles written by Jim Nicholson and published in the Grundy County Herald in 1977. Jim’s articles were meant to shed new light on “The Skirmish of Tracy City, Tenn.” I present the following transcription—Jackie Layne Partin) Maj. Bledsoe, Leader of Confederate Raid On Jan. 20, 1864, the Union garrison occupying Tracy City was attacked by a Confederate raiding party on horseback. In the “Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies,” this Civil War action is denoted “The Skirmish of Tracy City, Tenn.” An article about this skirmish appeared in the recently published “Grundy County, 1844-1976.” It was based, however, almost entirely on reports which were submitted by Union officers after the attack. The Official Records, unfortunately, contain no statements by officers of the Confederate party which would add to our perspective of this Civil War action in Tennessee. Thus our earlier article bore a likeness to an old cowboy movie in that it was dominated by an action—Confederates riding into town, shooting the place up, putting the torch to buildings, demanding a surrender, and, not getting one, riding off into the fading sunlight of a winter afternoon. But what did this sound and fury signify? Just as the typical cowboy movie only implied a period in the history of the Trans-Mississippi West and roughed in some Western place for its setting, so was it understood that the time of our skirmish was the Civil War and our place Tracy City, a mining town of Cumberland Mountain. -

Improving Labor Practices + Supply Improving Labor Practices + Supply Additional Key Issues to Cover in a Code

POCKET GUIDE www.sustaincoffee.org IMPROVING LABOR PRACTICES + SUPPLY IMPROVING LABOR PRACTICES + SUPPLY ADDITIONAL KEY ISSUES TO COVER IN A CODE Introduction Good labor practices should be the norm OF CONDUCT for each of these categories of workers Coffee depends on workers to maintain In addition to labor conditions, a code of conduct should cover business ethics and throughout the coffee supply chain, coffee fields, pick the ripe cherries, expectations and explain how the policy will be implemented. We recommend that it also but we continue to confront forced labor, process them into green coffee and roast cover environmental expectations. Draft text for each of these sections can be found at human trafficking and child labor in coffee. and package them. https://www.sustaincoffee.org/improved-labor-practices-and-supply-group/. Within the coffee production system we Do we really understand what these terms have a number of worker types: Full-Time, mean? We need to in order to begin Part-Time, Temporary, Multi-Party, and discussions and to better detect these Business Ethics Environmental Policy issues in coffee production. Implementation Ambiguous or Disguised Employment. Legal Compliance Sustainability Each of these is further defined below. This short guidance document provides Management Systems Bribery / Corruption Resource Consumption and overview of key terms, sets forth Coffee also has a number of different Pollution Prevention Grievance principles for good labor practices in Gifts / Hospitality labor supply systems. These can vary Mechanisms Waste Minimization from informal family labor and farmer coffee and guides users through a process Conflict of Interest Audits + Corrective or community labor exchange systems of considering and addressing risks. -

Slavery in the Fields and the Food We Eat

Coalition of Immokalee Workers . P.O. Box 603, Immokalee, FL 34143 239-657-8311 239-657-5055 [email protected] Slavery in the Fields and the Food We Eat In 21st century America, slavery remains woven into the fabric of our daily lives. On any given day, the tomatoes in the sandwiches we eat or the oranges in the juice we drink may have been picked by workers in involuntary servitude. Captive workers are held against their will by their employers through threats, and all too often the actual use of, violence. The CIW's Anti-Slavery Campaign is a worker-based approach to eliminating modern-day slavery in the agricultural industry. The CIW helps fight this crime by uncovering, investigating, and assisting in the federal prosecution of slavery rings preying on hundreds of farmworkers. Through this work, the CIW has brought the abysmal state of human rights in U.S. agriculture today to public light. Florida farm labor slavery prosecutions, 1997-2010: U.S. vs. Flores: In 1997, Miguel Flores and Sebastian Gomez were sentenced to 15 years each in federal prison on slavery, extortion, and firearms charges, amongst others. Flores and Gomez had a workforce of over 400 men and women in Florida and South Carolina, harvesting vegetables and citrus. The workers, mostly indigenous Mexicans and Guatemalans, were forced to work 10-12 hour days, 6 days per week, for as little as $20 per week, under the constant watch of armed guards. Those who attempted escape were assaulted, pistol-whipped, and even shot. The case was brought to federal authorities after five years of investigation by escaped workers and CIW members. -

Shroyer V Dollar Tree Stores

Page 1 1 of 1 DOCUMENT THERESA SHROYER, Plaintiff, v. DOLLAR TREE STORES, INC., Defendant. No. 3:09-CV-203 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE 2011 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 126522 November 1, 2011, Filed COUNSEL: [*1] For Theresa Shroyer, Plaintiff: Michael S Shipwash, Law Office of Michael Shipwash, Knoxville, TN. For Dollar Tree Stores, Inc., Defendant: Edward G Phillips, LEAD ATTORNEY, William J Carver, Kramer, Rayson LLP (Knox), Knoxville, TN. JUDGES: Thomas W. Phillips, United States District Judge. OPINION BY: Thomas W. Phillips OPINION MEMORANDUM OPINION I. Introduction This matter comes before the court on Defendant's Motion for Summary Judgment (Doc. 13) pursuant to Rule 56 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. Having read the parties' accompanying memoranda and thoroughly reviewed the record in this case, and for the reasons stated herein, this court finds that there are no genuine issues of material fact, and that Defendant is entitled to judgment as a matter of law. Defendant's motion for summary judgment (Doc. 13) is GRANTED and this case is DISMISSED. II. Statement of the Facts A. Defendant Dollar Tree's Policies and Procedures Defendant Dollar Tree Stores, Inc. ("Dollar Tree") operates more than 400 retail variety stores nationwide, includ- ing the Alcoa Highway, Deane Hill, and Chapman Highway stores in Eastern Tennessee. (Barnes Dec. ¶ 2.) At the time of the termination in question, Jerry Barnes was Dollar Tree's [*2] District Manager for Eastern Tennessee, and Bar- bara Leonard was Dollar Tree's Human Resources Manager for the Southeast United States, known as Zone 2, which includes all Dollar Tree stores in Eastern Tennessee. -

Tillman Furniture Company

TILLMAN Furniture STORE MANUAL May, 2021 STORE MANUAL UPDATES: Employees will be notified when changes have occurred and will be expected to visit the company website to view changes and/or print the manual. Go to www.TILLMANFURNITURE.net. At the very bottom of the page, click on the left dot. The dot is a link to the store manual. ©2019 All Your Retail All Rights Reserved | Powered by AllYourRetail.com ∙ ∙ INTRODUCTION Welcome to Tillman Furniture Company. This handbook is yours to keep for as long as you continue your association with our Company. We hope you will find the handbook useful. This handbook is not intended as a formal or exhaustive statement of employee rights and responsibilities. Nor is it a contract of employment. It is simply a summary of the Company's current policies, rules, procedures, and benefits. We feel very strongly that we must retain flexibility in making changes in the working conditions and benefits of our employees in order to meet future economic challenges. Accordingly, the Company reserves the right to amend, modify, and/or eliminate any of these policies, rules, procedures, and benefits. COMPANY HISTORY Herman Tillman, Sr. and B. F. Lemon formed a partnership on August 1, 1945 and opened Copiah Furniture Company on Marion Avenue in Crystal Springs. Mr. Lemon managed the business and Mr. Tillman provided the capital from his employment with Illinois Central Railroad. Within two years another store was opened on Ragsdale Avenue in Hazlehurst. The business prospered with Mr. Lemon's management and Mr. Tillman contribution of capital from his railroad job.