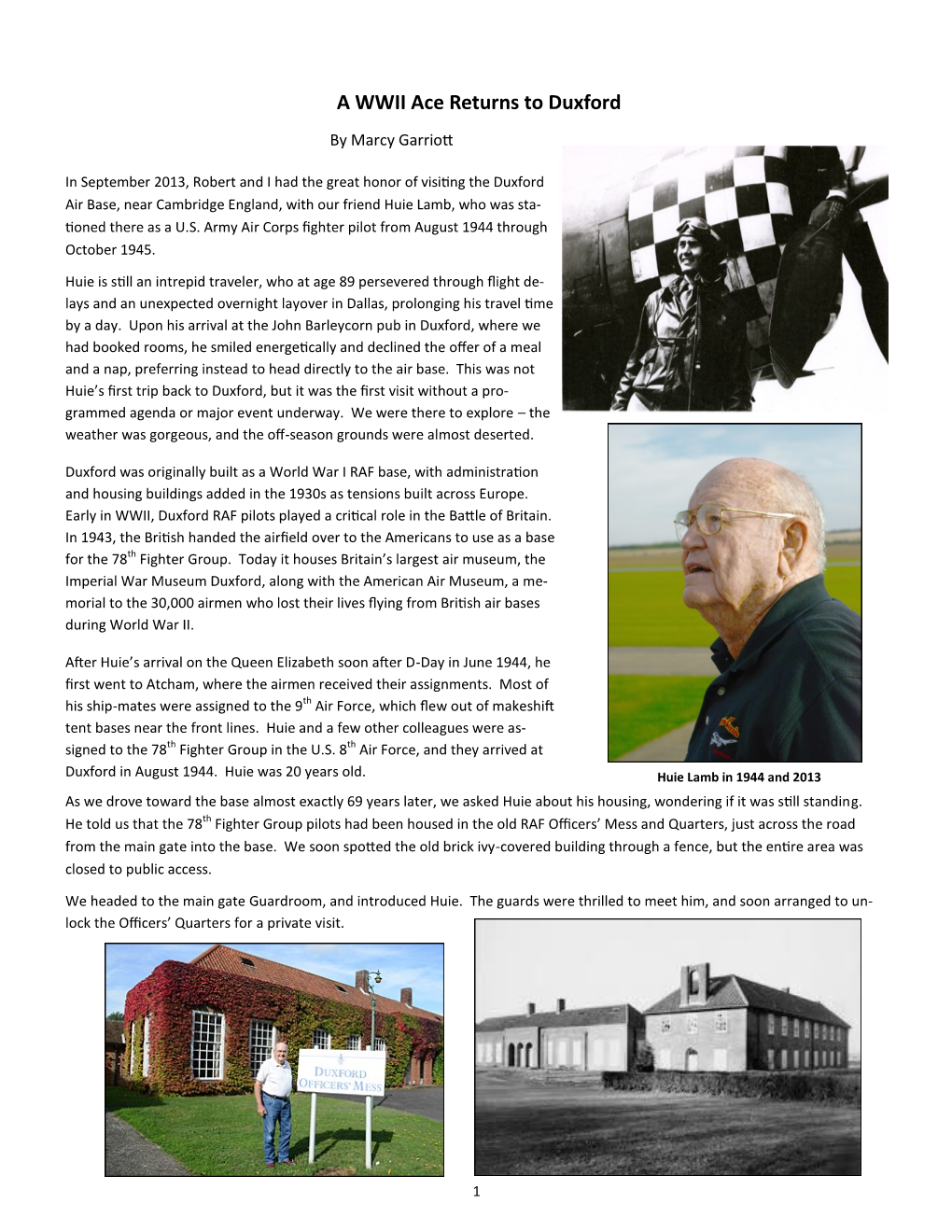

A WWII Ace Returns to Duxford

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Luftwaffe Wasn't Alone

PIONEER JETS OF WORLD WAR II THE LUFTWAFFE WASN’T ALONE BY BARRETT TILLMAN he history of technology is replete with Heinkel, which absorbed some Junkers engineers. Each fac tory a concept called “multiple independent opted for axial compressors. Ohain and Whittle, however, discovery.” Examples are the incandes- independently pursued centrifugal designs, and both encoun- cent lightbulb by the American inventor tered problems, even though both were ultimately successful. Thomas Edison and the British inventor Ohain's design powered the Heinkel He 178, the world's first Joseph Swan in 1879, and the computer by jet airplane, flown in August 1939. Whittle, less successful in Briton Alan Turing and Polish-American finding industrial support, did not fly his own engine until Emil Post in 1936. May 1941, when it powered Britain's first jet airplane: the TDuring the 1930s, on opposite sides of the English Chan- Gloster E.28/39. Even so, he could not manufacture his sub- nel, two gifted aviation designers worked toward the same sequent designs, which the Air Ministry handed off to Rover, goal. Royal Air Force (RAF) Pilot Officer Frank Whittle, a a car company, and subsequently to another auto and piston 23-year-old prodigy, envisioned a gas-turbine engine that aero-engine manufacturer: Rolls-Royce. might surpass the most powerful piston designs, and patented Ohain’s work detoured in 1942 with a dead-end diagonal his idea in 1930. centrifugal compressor. As Dr. Hallion notes, however, “Whit- Slightly later, after flying gliders and tle’s designs greatly influenced American savoring their smooth, vibration-free “Axial-flow engines turbojet development—a General Electric– flight, German physicist Hans von Ohain— were more difficult built derivative of a Whittle design powered who had earned a doctorate in 1935— to perfect but America's first jet airplane, the Bell XP-59A became intrigued with a propeller-less gas- produced more Airacomet, in October 1942. -

86'- ' Its Departure for Overseas Duty in Great Britain

CHAa IV *I 'THE STORY OP VIII FIGHT CM " began The formation of a long-range fighter organization VIII Interceptor early in 1942 with the activation of the Fighter Comnand, at Coand, which later was renamed the VIII 1, 1942. The Comanding Selfridge Field, Michigan on February who had been in oamand Officer was Colonel Laurence P. Hiokey, VIII Interceptor of the Sixth Pursuit Wing, from which the to Charleston, South Command was developed. The Command moved to be close to the Carolina on the 11th of February in. order located at Savannah, headquarters of the 8th Air Force, then The 8th Air Georgia, where it was preparing for embarkation. be prepared to carry Force was organised in such a way aa to invasion of North Afrioa out the "Torch Plan' for the eventual General Frank O'D. which oame in November, 1942. Brigadier shortly before Hunter assumed oommand of the organisation Officer Richard The author is indebted to Chief Warrant (*1 - at VIII Fighter A. Bates of the A-2 Section (Intelligence) history of the Comnand. Comand for the facts about the early whn it _as activated in Febru- Mr. Bates was its lst Stergeant of the became Teohnical Sergeant ana Chief Olerk ary, 1942, hiatorian until July IntelligenCe Section and was its official data was not otherwise available. The Sta- 1943. Much of this later, has Control Office which was establiahed muoh tistical but these facts proided-invaluable data on later operations, from his own records, from his friends "'oaptured for posterity" are based on his and from a most retentive memory. -

United States Air Force and Its Antecedents Published and Printed Unit Histories

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE AND ITS ANTECEDENTS PUBLISHED AND PRINTED UNIT HISTORIES A BIBLIOGRAPHY EXPANDED & REVISED EDITION compiled by James T. Controvich January 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTERS User's Guide................................................................................................................................1 I. Named Commands .......................................................................................................................4 II. Numbered Air Forces ................................................................................................................ 20 III. Numbered Commands .............................................................................................................. 41 IV. Air Divisions ............................................................................................................................. 45 V. Wings ........................................................................................................................................ 49 VI. Groups ..................................................................................................................................... 69 VII. Squadrons..............................................................................................................................122 VIII. Aviation Engineers................................................................................................................ 179 IX. Womens Army Corps............................................................................................................ -

There Is a Map of Sawston Is HERE to Assist with Locations Mentioned.)

(A Streetfull of Sad Sacks has been published on this site, without the authority of the author or publisher, after extensive enquiry to discover their identity and permission. Searches have been made in the USA, to seek this authority, via the Air Force Historical Research Agency http://www.afhra.af.mil/ and the Muir S. Fairchild Research Information Center without any trace. ) (There is a map of Sawston is HERE to assist with locations mentioned.) (Examine this location in Google Street View.) DURING THE SUMMER OF 1943 UNITS OF THE UNITED STATES ARMY AND ITS EIGHTH AIR FORCE MOVED INTO SAWSTON, WHEN THEY LEFT IN OCTOBER 1945, LIFE IN THE VILLAGE WAS NEVER QUITE THE SAME AGAIN Page 1 of 75 www.family.nigellane.com The Sad Sack An embodiment of the Army's lowest-rated born loser, George Baker's cartoon character made his name in World War Two as the hapless draftee who lost out in every conceivable military situation. Sergeant Baker's comic strip in the service magazine Yank, published on Sundays price 3d, depicted the Sack's confrontations with the perils and perplexities of wartime service life. In all his dealings - with fellow soldiers, top brass, foreign nationals, prostitutes and the rest of the world in general - the little private always came off second best. But he remained the Army's hero, a trusting soul whose own little world of dreamy optimism was constantly devastated by unforeseen disaster. His name derived from the drill sergeant’s parade-square name for all new doughboys. To that redoubtable NCO all recruits were "sad -

Full Logs for Previous Years Are in the Members Area Dec Thu 9 Club

Log 25/01/2011 18:14 2010 Full logs for previous years are in the Members Area Dec Thu 9 Club Night Special at the Dealership Free drinks, food and a storeful of christmas presents to buy - HOG heaven! Plus we were delighted to present Colin with a pocket watch to mark his years of service as a Road Captain. He is stepping down to take things a bit easier. Nov Sat 27 End of Season Party What can we say? Fantastic party in a superb venue, great food, two excellent bands and DJ Robbie to keep things moving along nicely. Norm's piece was made even funnier by Carl's inspired playing along and the impromptu Morris Dancers did impressively well. The photos from Axel and Ian capture some of the moments, but you had to be there to experience the wonderfully relaxed and friendly atmosphere of a major Hogsback event Sun 14 Remembrance Ride Gary ended up with a wet old day for his first ride as leader. Nevertheless 35 bikes joined him from both Hogsback and Thames Valley Chapters for the Remembrance ride to Shamley Green. It was a well researched and very good ride. Well done Gary and Kaz! Sun 7 Goodwood breakfast Brisk run to Goodwood for breakfast and back again for the Sunday Roast - marvellous! Sat 6 Club Night Fireworks Special Brilliant night of food, fun and fab fireworks - plus we handed over a cheque for £320 to The Alzheimers Society, said a proper hello to our new Road Crew (Cliff, Robin and Dave), marked the promotion of Dell and Steve to Road Captain, and recognised Axel as one of our official Chapter Photographers. -

ADC and Antibomber Defense, 1946-1972

Obtained and posted by AltGov2: www.altgov2.org ADC HISTORICAL STUDY NO. 39 THE AEROSPACE DEFENSE COMMAND AND ANTIBOMBER DEFENSE 194& -1972 ADCHO 73-8-17 FOREWORD" The resources made available to the Aerospace Defense Command (and the predecessor Air Defense Command) for defense against the manned bomber have ebbed and flowed with changes in national military policy. It is often difficult to outline the shape of national policy, however, in a dynamic society like that of the United States. Who makes national policy? Nobody, really. The armed forces make recommenda tions, but these are rarely accepted, in total, by the political administration that makes the final pbrposals to Congress. The changes introduced at the top executive level are variously motivated. The world political climate must be considered, as must various political realities within the country. Cost is always a factor and a determination must be made as to the allocation of funds for defense as opposed to allocations to other government concerns. The personalities, prejudices and predilections of the men who occupy high political office invariably affect proposals to Congress. The disposition of these proposals, of course, is in the hands of Congress. While the executive branch of the government is pushect' and pulled in various directions, Congress is probably subject to heavier pressures. Here, again, the nature of the men who occupy responsible positions within the Congress often affect the decisions of Congress. ·National policy, then, is the product of many minds and is shaped by many diverse interests. The present work is a recapitulation and summarization of three earlier monographs on this subject covering the periods 1946-1950 (ADC Historical Study No. -

The Old Pangbournian Record Volume 2

The Old Pangbournian Record Volume 2 Casualties in War 1917-2020 Collected and written by Robin Knight (56-61) The Old Pangbournian Society The Old angbournianP Record Volume 2 Casualties in War 1917-2020 Collected and written by Robin Knight (56-61) The Old Pangbournian Society First published in the UK 2020 The Old Pangbournian Society Copyright © 2020 The moral right of the Old Pangbournian Society to be identified as the compiler of this work is asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, “Beloved by many. stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any Death hides but it does not divide.” * means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the Old Pangbournian Society in writing. All photographs are from personal collections or publicly-available free sources. Back Cover: © Julie Halford – Keeper of Roll of Honour Fleet Air Arm, RNAS Yeovilton ISBN 978-095-6877-031 Papers used in this book are natural, renewable and recyclable products sourced from well-managed forests. Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro, designed and produced *from a headstone dedication to R.E.F. Howard (30-33) by NP Design & Print Ltd, Wallingford, U.K. Foreword In a global and total war such as 1939-45, one in Both were extremely impressive leaders, soldiers which our national survival was at stake, sacrifice and human beings. became commonplace, almost routine. Today, notwithstanding Covid-19, the scale of losses For anyone associated with Pangbourne, this endured in the World Wars of the 20th century is continued appetite and affinity for service is no almost incomprehensible. -

January 1998 6 March 98’

What’s on Vicky Hall - Program Secretary 2 January 98’..................‘Flying with the Red Arrows’ - Dick Storer 6 February 98’...‘50yrs of Bentwaters inc. F.I.D.O.’ - Norman Rose Volume 1 No.4 January 1998 6 March 98’......................‘Flying the P51 Mustang’ - Howard Cook 3 April 98’..................................A.G.M. & Photo/Slide Competition 1 May 98’......‘Decoy Site (Wartime Deception)’ - Huby Fairhead Newsletter Contributions NEWSLETTER If you have an article or a story you would like to share with the other members of the Society then please send it to me.... Alan Powell - Newsletter Editor 16 Warren Lane Tel: Ipswich Martlesham Heath 622458 Ipswich IP5 7SH Martlesham Heath Aviation Society RAF Martlesham Heath 356th Fighter Group Committee Contacts Contents Chairman Martyn Cook (01394) 671210 Page 2..................................................................Editorial Vice Chairman Bob Dunnett (01473) 624510 Page 2................................................Savannah Reunion Secretary Alan Powell (01473) 622458 Treasurer Russell Bailey (01473) 715938 Page 6.................................Monthly Meeting Round Up Program Sec. Vicky Hall (01473) 720004 Membership Sec. Jack & Jean Sweetman (01473) 723349 Page 7................................................Photo Competition Rag Trade David Bloomfield (01473) 686204 Page 7....................Major General Donald Strait (Ret’d) Catering Ethel & Roy Gammage (01473) 623420 Photography Don Kitt (01473) 742332 Page 8........................Bawdsey Radar Research Group Museum Adviser Tony Errington (01473) 741574 Page 10.......................................................James Stuart Produced by: Jack Russell Designs Page 11....................................Visit to Marshalls Airport EDITORIAL I too was a B-24 Aircraft Commander, also assigned to the 389th The first Newsletter of 1998 and I very much hope that members will Bomb Group at Hethel. I was privileged to fly 3 missions with Col. -

A Review and Statistical Modelling of Accidental Aircraft Crashes Within Great Britain MSU/2014/07

Harpur Hill, Buxton Derbyshire, SK17 9JN T: +44 (0)1298 218000 F: +44 (0)1298 218590 W: www.hsl.gov.uk Loughborough University Loughborough Leicestershire LE11 3TU UK P: +44 (0)1509 223416 F: +44 (0)1509 223981 http://www.lboro.ac.uk/transport 12.09.2014 A Review and Statistical Modelling of Accidental Aircraft Crashes within Great Britain MSU/2014/07 HSL Report Content Loughborough University Report Content Report Approved Report Approved Andrew Curran David Pitfield for Issue By: for Issue By: Date of Issue: 12/09/2014 Date of Issue: 12/09/2014 Lead Author: Emma Tan Lead Author: David Gleave Contributing Contributing Nick Warren David Pitfield Author(s): Author(s): Technical Technical David Pitfield / Nick Warren Reviewer(s): Reviewer(s): David Gleave David Pitfield / Editorial Reviewer: Charles Oakley Editorial Reviewer: David Gleave HSL Project Loughborough PH06315 N/A Number: Project Number: HSL authored 7 ,8 ,9 Appendix (a) Loughborough 3 ,4 ,5 ,6 ,10 ,12 sections and Appendix (b) authored sections Appendix (c ) HSL/Loughborough HSL/Loughborough 1, 2, 11 1, 2, 11 Joint authorship Joint authorship 1, 2 ,7 ,8 ,9 ,11 , Loughborough HSL Quality 3 ,4 ,5 ,6 ,10 ,12 Appendix (a) and quality approved approved sections Appendix (c ) Appendix (b) sections DISTRIBUTION Matthew Lloyd-Davies Technical Customer Tim Allmark Project Officer Gary Dobbin HSL Project Manager Andrew Curran Science and Delivery Director Charles Oakley Mathematical Sciences Unit Head David Pitfield Loughborough University David Gleave Loughborough University © Crown copyright (2014) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Background One of the hazards associated with nuclear facilities in the United Kingdom is accidental impact of aircraft onto the sites. -

Uk Reunion Tour Thursday 19Th to Tuesday 24Th September 2019

384TH BOMB GROUP – UK REUNION TOUR THURSDAY 19TH TO TUESDAY 24TH SEPTEMBER 2019 Specially arranged for members of the 384th Bombardment Group, their family and friends! This bespoke UK Reunion Tour visits sites in East Anglia associated with the unit and the wider US 8th Air Force and gives the opportunity to remember those who made the ultimate sacrifice at the American War Cemetery. You’ll also enjoy a day at the Imperial War Museum in Duxford where the spectacular air show promises to be a highlight. The tour starts and finishes in the UK giving you the opportunity to make your own flight arrangements from the USA to London’s Heathrow Airport. Day 1 – Thursday 19th September 2019 Upon arrival at London Heathrow you have the option to make your own way to the hotel or join the included midday private coach transfer to Cambridge where you’ll check-in to the Doubletree by Hilton Cambridge Belfry. The hotel, which is located on the outskirts of the city, enjoys a tranquil lakeside setting making it both a comfortable and peaceful retreat for your 5-night stay. The remainder of the afternoon is at leisure giving you time to relax before you join fellow members of the group for a welcome dinner served in the hotel’s restaurant. Day 2 – Friday 20th September Breakfast is served in the hotel. Today you’ll visit the county of Suffolk, which during the Second World was considered the heart of ‘Little America’. By the summer of 1944 hundreds of thousands of US airmen were based in East Anglia. -

North Weald Spiritthe North Weald Airfield History Series | Booklet 3

The of North Weald SpiritThe North Weald Airfield History Series | Booklet 3 The Battle of Britain in 1940 and our Finest Hour Epping Forest District Council www.eppingforestdc.gov.uk North Weald Airfield Hawker Hurricane V6692, GN-O, of 249 Squadron was flown by P/O Richard ‘George’ Airfield North Weald Museum Hurricanes from 249 Squadron taking off on a scramble, believed to Barclay on a Squadron sweep on 7 November 1940. It has the Sky spinner of B Flight. have been photographed by French pilot Georges Perrin RAF Squadrons operating from North One of his combat reports is also featured below. Weald during 1940 56 Squadron (28 February - 10 May 1940 [from Martlesham Heath], 12 - 31 May 1940 [from Gravesend], 4 June - 1 September 1940. Also temporarily based at Rochford where it was filmed) 151 Squadron (4 August 1936 - 13 May 1940, 20 May - 29 August 1940) 111 Squadron (30 May - 4 June 1940) North Weald Airfield North Weald Museum 249 Squadron (1 September 1940 - 21 May 1941) 46 Squadron (8 November - 14 December 1940) Into action! 257 Squadron (8 October - 7 November 1940) 604 Squadron ( September 1939 - January 1940) North Weald was in the front line 25 Squadron (16 January - 19 June 1940, of the aerial battles in 1940... 1 September - 8 October 1940) North Weald Airfield North Weald Museum RAF North Weald was a front line fighter station in Sector E London itself. This gave the Airfield a well-needed respite of 11 Group guarding London and the south east. At the and enabled the squadrons to recover and regroup. -

Historical Brief Installations and Usaaf Combat Units In

HISTORICAL BRIEF INSTALLATIONS AND USAAF COMBAT UNITS IN THE UNITED KINGDOM 1942 - 1945 REVISED AND EXPANDED EDITION OFFICE OF HISTORY HEADQUARTERS THIRD AIR FORCE UNITED STATES AIR FORCES IN EUROPE OCTOBER 1980 REPRINTED: FEBRUARY 1985 FORE~ORD to the 1967 Edition Between June 1942 ~nd Oecemhcr 1945, 165 installations in the United Kingdom were used by combat units of the United States Army Air I"orce~. ;\ tota) of three numbered .,lr forl'es, ninc comllklnds, frJur ;jfr divi'iions, )} w1.l\~H, Illi j(r,IUpl', <lnd 449 squadron!'! were at onE' time or another stationed in ',r'!;rt r.rftaIn. Mnny of tlal~ airrll'lds hnvc been returned to fann land, others havl' houses st.lnding wh~rr:: t'lying Fortr~ss~s and 1.lbcratorR nllce were prepared for their mis.'ilons over the Continent, Only;l few rcm:l.1n ;IS <Jpcr.Jt 11)11., 1 ;'\frfll'ldH. This study has been initl;ltcd by the Third Air Force Historical Division to meet a continuin~ need for accurate information on the location of these bases and the units which they served. During the pas t several years, requests for such information from authors, news media (press and TV), and private individuals has increased. A second study coverin~ t~e bases and units in the United Kingdom from 1948 to the present is programmed. Sources for this compilation included the records on file in the Third Air Force historical archives: Maurer, Maurer, Combat Units of World War II, United States Government Printing Office, 1960 (which also has a brief history of each unit listed); and a British map, "Security Released Airfields 1n the United Kingdom, December 1944" showing the locations of Royal Air Force airfields as of December 1944.