Cranfield Institute of Technology Saed Al-Suliaman the Feasibility of Liberalisation Or Deregulation of Air Transport in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Capacity to and from Japan As from 30 March 2014

10 March 2014 More capacity to and from Japan as from 30 March 2014 Dear Customer, Effective 30 March 2014, Air France-KLM-Martinair Cargo will be adding Tokyo Haneda (HND) to its schedule. With central Tokyo less than 30 minutes away, Haneda airport is an ideal gateway to the distribution and industrial centers of the largest consumer market in Japan. The air cargo facility of Haneda airport is equipped to handle all your cargo shipments including temperature sensitive commodities. Biggest port of Japan Please check out Air France-KLM-Martinair Cargo’s overall flight schedule to and from Japan here: Flight number Aircraft From To Departure Arrival Day type New AF272 B772X CDG HND 10.55 06.00 + Daily New AF274 B77W CDG HND 23:25 18:20 Daily AF276 B77W CDG NRT 13:40 08:35+ Daily AF284 B787 CDG NRT 22:20 16:55+ Daily AF6760 B77X CDG NRT 12:25 07:05+ 5 AF292 B772 CDG KIX 13:35 08:10+ Daily New AF279 B772X HND CDG 07:35 13:20 Daily New AF293 B77W HND CDG 22:15 04:00+ Daily AF275 B77W NRT CDG 11:45 17:10 Daily AF273 B787 NRT CDG 14:35 18:10 Daily AF6775 B77X NRT CDG 09:05 18:30 6 AF291 B772 KIX CDG 11:30 17:10 Daily KL861 B74E AMS NRT 14:40 08:30+1 Daily KL863 B772 AMS NRT 17:50 12:00+1 4 KL867 B772 AMS KIX 14:55 08:40+1 Daily KL869 B772 AMS FUK 14:45 08:20+ 1356 KL862 B74E NRT AMS 10:30 15:00 Daily KL864 B772 NRT AMS 13:50 18:30 5 KL868 B772 KIX AMS 10:35 15:10 Daily KL870 B772 FUK AMS 10:25 15:10 1246 Air France-KLM-Martinair Cargo is pleased to offer you competitive solutions with this extra capacity. -

Milan Linate (LIN) J Ownership and Organisational Structure the Airport

Competition between Airports and the Application of Sfare Aid Rules Volume H ~ Country Reports Italy Milan Linate (LIN) J Ownership and organisational structure The airport is part of Gruppo SEA (Milan Airports). Ownership is 14.6% local government and 84.6% City of Milan. Other shareholders hold the remaining 0.8%. Privatisation (partial) was scheduled for the end of 2001 but was stopped after the events of 11th September. Now the proposed date is October 2002 but this has still to be finalised. Only 30% of the shareholding will be moved into the private sector with no shareholder having more than 5%. There are no legislative changes required. The provision of airport services is shared between ENAV (ATC), Italian police (police), SEA (security), ATA and SEA Handling (passenger and ramp handling), Dufntal (duty-free) and SEA Parking (car parking). There are no current environmental issues but, in the future, there is a possible night ban and charges imposed according to aircraft noise. 2 Type ofairpo Milan Linate is a city-centre (almost) airport that serves mainly the scheduled domestic and international market with a growing low-cost airline presence (Buzz, Go). There is very little charter and cargo traffic but some General Aviation. The airport is subject to traffic distribution rules imposed by the Italian government with the aim of 'encouraging' airlines to move to Malpensa. Traffic Data (2000) Domestic fíghts Scheduled Charter Total Terminal Passengers (arrivals) 2 103 341 _ 2 103 341 Terminal Passengers (departures) 2 084 008 -

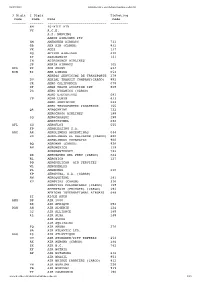

TRAMS Master Vendor ID List 2/27/2007 Air Interface ID Travel

2/27/2007 TRAMS Master Vendor ID List Air Name Airline No. Travel Category Vendor Id Profile No. Interface ID Abx Air 832 Air 2001 5 GB Action Airlines 410 Air 2002 6 XQ Ada Air 121 Air 2003 7 ZY Adria Airways 165 Air 2004 8 JP Aer Arann Teo 684 Air 2005 9 RE Aer Lingus P.l.c. 53 Air 2006 10 EI Aero Asia International (private) Ltd. 532 Air 2007 11 E4 Aero California 78 Air 2008 12 JR Aero Costa Rica Acori S.a. 802 Air 2009 13 ML Aero Lloyd Flugreisen Gmbh And Co. Luftv 633 Air 2010 14 YP Aerocaribe 723 Air 2011 15 QA Aerochago Airlines S.a. 198 Air 2012 16 G3 Aeroejecutivo S.a. De C.v. 456 Air 2013 17 SX Aeroflot-russian International Airlines 555 Air 2014 18 SU Aerolineas Argentinas 44 Air 2015 19 AR Aerolineas Centrales De Colombia (aces) 137 Air 2016 20 VX Aerolineas Dominicanas S.a. (dominair) 725 Air 2017 21 YU Aerolineas Internacionales S.a. De C.v. 440 Air 2018 22 N2 Aeromar C. Por. A. 926 Air 2019 23 BQ Aeromexico-aerovias De Mexico S.a. De C. 139 Air 2020 24 AM Aeromonterrey S.a. De C.v. 722 Air 2021 25 7M Aeroperlas 828 Air 2022 26 WL Aeroperu - Empresa De Transportes Aereos 210 Air 2023 27 PL Aeroservicios Ecuatorianos C.a. 746 Air 2024 28 2A Aerotransportes Mas De Carga S.a. De C. 865 Air 2025 29 MY Aerovias Colombianas Ltd. (arca) 158 Air 2026 30 ZU Aerovias Venezolanas S.a. -

Characteristics Monitor Aviation Market Netherlands – United Arab Emirates

Amsterdam, November 2017 Commissioned by Ministry of Infrastructure and Environment Characteristics Monitor Aviation Market Netherlands – United Arab Emirates 2009-2017 Thijs Boonekamp Joost Zuidberg SEO Economic Research - Roetersstraat 29 - 1018 WB Amsterdam - T (+31) 20 525 1630 - www.seo.nl - [email protected] ABN-AMRO IBAN: NL14ABNA0411744356 BIC: ABNANL2A - ING: IBAN: NL96INGB0004641100 BIC: INGBNL2A KvK Amsterdam 41197444 - BTW NL 003023965 B01 “Solid research, sound advice” SEO Amsterdam Economics carries out independent applied economic research on behalf of national and international clients – both public institutions and private sector clients. Our research aims to make a major contribution to the decision-making processes of our clients. Originally founded by, and still affiliated with, the University of Amsterdam, SEO Amsterdam Economics is now an independent research group but retains a strong academic component. Operating on a nonprofit basis, SEO continually invests in the intellectual capital of its staff by granting them time to pursue continuing education, publish in academic journals, and participate in academic networks and conferences. As a result, our staff is fully up to date on the latest economic theories and econometric techniques. SEO report no 2017-79 Copyright © 2018 SEO Amsterdam. All rights reserved. It is permissible to use the data provided in this report in articles, studies and college syllabuses, provided that the source is clearly stated. Data provided in this report are not to be used for commercial purposes without prior permission by the author(s). Permission can be acquired through [email protected] CHARACTERISTICS MONITOR AVIATION MARKET NETHERLANDS – UNITED ARAB EMIRATES i Summary Over the last eight years, airlines from the United Arab Emirates have established a stronger position in the market between the Netherlands and the United Arab Emirates. -

3 Digit 2 Digit Ticketing Code Code Name Code ------6M 40-MILE AIR VY A.C.E

06/07/2021 www.kovrik.com/sib/travel/airline-codes.txt 3 Digit 2 Digit Ticketing Code Code Name Code ------- ------- ------------------------------ --------- 6M 40-MILE AIR VY A.C.E. A.S. NORVING AARON AIRLINES PTY SM ABERDEEN AIRWAYS 731 GB ABX AIR (CARGO) 832 VX ACES 137 XQ ACTION AIRLINES 410 ZY ADALBANAIR 121 IN ADIRONDACK AIRLINES JP ADRIA AIRWAYS 165 REA RE AER ARANN 684 EIN EI AER LINGUS 053 AEREOS SERVICIOS DE TRANSPORTE 278 DU AERIAL TRANSIT COMPANY(CARGO) 892 JR AERO CALIFORNIA 078 DF AERO COACH AVIATION INT 868 2G AERO DYNAMICS (CARGO) AERO EJECUTIVOS 681 YP AERO LLOYD 633 AERO SERVICIOS 243 AERO TRANSPORTES PANAMENOS 155 QA AEROCARIBE 723 AEROCHAGO AIRLINES 198 3Q AEROCHASQUI 298 AEROCOZUMEL 686 AFL SU AEROFLOT 555 FP AEROLEASING S.A. ARG AR AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS 044 VG AEROLINEAS EL SALVADOR (CARGO) 680 AEROLINEAS URUGUAYAS 966 BQ AEROMAR (CARGO) 926 AM AEROMEXICO 139 AEROMONTERREY 722 XX AERONAVES DEL PERU (CARGO) 624 RL AERONICA 127 PO AEROPELICAN AIR SERVICES WL AEROPERLAS PL AEROPERU 210 6P AEROPUMA, S.A. (CARGO) AW AEROQUETZAL 291 XU AEROVIAS (CARGO) 316 AEROVIAS COLOMBIANAS (CARGO) 158 AFFRETAIR (PRIVATE) (CARGO) 292 AFRICAN INTERNATIONAL AIRWAYS 648 ZI AIGLE AZUR AMM DP AIR 2000 RK AIR AFRIQUE 092 DAH AH AIR ALGERIE 124 3J AIR ALLIANCE 188 4L AIR ALMA 248 AIR ALPHA AIR AQUITAINE FQ AIR ARUBA 276 9A AIR ATLANTIC LTD. AAG ES AIR ATLANTIQUE OU AIR ATONABEE/CITY EXPRESS 253 AX AIR AURORA (CARGO) 386 ZX AIR B.C. 742 KF AIR BOTNIA BP AIR BOTSWANA 636 AIR BRASIL 853 AIR BRIDGE CARRIERS (CARGO) 912 VH AIR BURKINA 226 PB AIR BURUNDI 919 TY AIR CALEDONIE 190 www.kovrik.com/sib/travel/airline-codes.txt 1/15 06/07/2021 www.kovrik.com/sib/travel/airline-codes.txt SB AIR CALEDONIE INTERNATIONAL 063 ACA AC AIR CANADA 014 XC AIR CARIBBEAN 918 SF AIR CHARTER AIR CHARTER (CHARTER) AIR CHARTER SYSTEMS 272 CCA CA AIR CHINA 999 CE AIR CITY S.A. -

Study on the Economic Developments of the EU Air Transport Market

Study on the economic developments of the EU Air Transport Market FINAL REPORT Written by: EGIS / SEO 16 July 2020 STUDY ON THE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS OF THE EU AIR TRANSPORT MARKET 1/238 FINAL REPORT EUROPEAN COMMISSION Directorate-General for Mobility and Transport Directorate E — Aviation Unit E.1 — Aviation Policy Contact: MOVE E1 Secretariat E-mail: [email protected] European Commission B-1049 Brussels EUROPEAN COMMISSION Study on the economic developments of the EU Air Transport Market Final Report EUROPEAN COMMISSION Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) The information given is free, as are most calls (though some operators, phone boxes or hotels may charge you). LEGAL NOTICE This document has been prepared for the European Commission however it reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://www.europa.eu). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2021 ISBN 978-92-76-29357-6 doi: 10.2832/561694 © European Union, 2021 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Image © Dmitrijs Mihejevs Directorate-General for Mobility and Transport Aviation Policy MOVE/E1/SER/2019-266/SI2.809800 STUDY ON THE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS OF THE EU AIR TRANSPORT MARKET – FINAL REPORT Document information GENERAL INFORMATION -

Maintenance Planning Optimisation for the Boeing 737 Next Generation

Maintenance Planning Optimisation for the Boeing 737 Next Generation Masters Thesis By ir. Anthony K. Muchiri Supervisors: Prof. ir Klaas Smit ing. Willem van Steenis Delft/ Schiphol East, 30 May 2002 Colophon Colophon Final Report Title: Maintenance Planning Optimisation for the Boeing 737 Next Generation Author: Anthony K. Muchiri Date: Thursday, 30 May 2002 Board Of Examiners: Prof. Ir. K. Smit - TU Delft (Coach) Ir. B. Agusdinata - TU Delft ing. W. van Steenis - Transavia Airlines (Supervisor) Ir. R. Hol - Transavia Airlines Delft University of Technology Transavia Airlines Faculty of Aerospace Engineering Technical Department Department of Industrial Engineering Maintenance Planning & Support and Technical Management P.O. Box 7777, 1118 ZM Schiphol Airport P.O. Box 5058, 2600 GB Delft The Netherlands The Netherlands i Preface Preface This thesis represents the results of my graduation assignment, a research project carried out to conclude the Master Phase of the Industrial Engineering Department, Faculty of Aerospace Engineering, of the Delft University of Technology. The assignment was assigned and carried out at the Maintenance Planning and Support (MP& S) department of Transavia Airline’s Technical Department, and it entails the optimisation of maintenance planning for the 737 Next Generation fleet of the airline. The report has been subdivided into five chapters, and it can be read as follows: - For readers interested in the development of a new maintenance planning strategy, Chapters 3 and 4.4 are recommended - For readers interested in the analysis of the current situation and the proposed situation, it is recommended that they read Chapter 4.4 - For readers interested in the conclusions and recommendations, they should look at Chapter 5 - For readers interested in the development of the whole research, all chapters and Appendix documents are recommended. -

Prospectus Dated 12 December 2012 Air France-KLM € 500,000,000

Prospectus dated 12 December 2012 Air France-KLM € 500,000,000 6.250 per cent. Notes due 18 January 2018 unconditionally and irrevocably guaranteed by Société Air France and KLM acting as several but not joint guarantors (cautions conjointes) (ISIN: FR0011374099) Issue Price: 99.451 per cent. of the aggregate principal amount of the Notes This document constitutes a prospectus (the "Prospectus") for the purposes of Article 5.3 of Directive 2003/71/EC of the European Parliament and the Council dated 4 November 2003, as amended (which includes the amendments made by Directive 2010/73/EU of the European Parliament and the Council dated 24 November 2010). The € 500,000,000 6.250 per cent. notes due 18 January 2018 (the "Notes") of Air France-KLM (the "Issuer") will be issued outside the Republic of France on 14 December 2012 (the "Issue Date") with the benefit of an irrevocable and unconditional guarantee (the "Guarantee", as described in the section "Description of the Guarantee" below) of Société Air France and Koninklijke Luchtvaart Maatschappij N.V. ("KLM") (the "Guarantors", as described in the section "Description of the Guarantors" below) acting as several but not joint guarantors (cautions conjointes), to the extent of 60% and 40%, respectively, of any amounts due by the Issuer under the Notes. Each Note will bear interest on its principal amount from (and including) the Issue Date to (but excluding) 18 January 2018 at a fixed rate of 6.250 per cent. per annum payable annually in arrear on 18 January in each year and commencing on 18 January 2014 with a long first coupon in respect of the period, from and including, the Issue Date up to, but excluding 18 January 2014, as further described in the section "Terms and Conditions of the Notes – Interest" of this Prospectus. -

Annual Report 2019 Lufthansagroup.Com Lufthansagroup.Com/Investor-Relations the Lufthansa Group

Annual Report 2019 CREATING SUSTAINABLE VALUE lufthansagroup.com lufthansagroup.com/investor-relations The Lufthansa Group The Lufthansa Group is the leading European airline group. It is composed of the segments Network Airlines, Eurowings and Aviation Services. T001 KEY FIGURES LUFTHANSA GROUP 1) 2019 2018 Change 2019 figures in % Revenue and result Total revenue €m 36,424 35,542 2 of which traffic revenue €m 28,136 27,801 1 Operating expenses €m 37,124 35,164 6 Adjusted EBITDA €m 4,718 5,016 – 6 Adjusted EBIT €m 2,026 2,836 – 29 36,424 EBIT €m 1,857 2,974 – 38 Revenue in EUR m Net profit/loss €m 1,213 2,163 – 44 Key balance sheet and cash flow statement figures Total assets €m 42,659 38,213 12 Equity ratio % 24.0 25.1 – 1.1 pts Net indebtedness €m 6,662 3,489 91 2,026 Pension provisions €m 6,659 5,865 14 Adjusted EBIT in EUR m Cash flow from operating activities €m 4,030 4,109 – 2 Capital expenditure (gross) 2) €m 3,559 3,757 – 5 Adjusted free cash flow €m 203 288 – 30 Key profitability and value creation figures 5.6 Adjusted EBITDA margin % 13.0 14.1 – 1.1 pts in % Adjusted EBIT margin % 5.6 8.0 – 2.4 pts Adjusted EBIT margin EBIT margin % 5.1 8.4 – 3.3 pts ROCE % 6.1 11.1 – 5.0 pts Adjusted ROCE % 6.6 10.6 – 4.0 pts Lufthansa share 3,559 Share price at year-end € 16.41 19.70 – 17 Capital expenditure in EUR m Earnings per share € 2.55 4.58 – 44 Proposed dividend per share € – 0.80 – 100 Traffic figures 3) Flights number 1,177,315 1,163,565 1 Passengers thousands 145,190 141,935 2 203 Available seat-kilometres millions 359,567 349,391 -

TRAMS Master Vendor ID List 10/8/2020 Air Travel Category

10/8/2020 TRAMS Master Vendor ID List Air Changes Since 09/26/18 Name Modified Airline No. Travel Category Vendor Id InterfaceID AFCNET 09/07/09 Air 2604 AFCNET Abx Air 10/11/05 832 Air 2001 GB Action Airlines 10/11/05 410 Air 2002 XQ Ada Air 10/11/05 121 Air 2003 ZY Adria Airways 10/11/05 165 Air 2004 JP Aer Arann Teo 10/11/05 684 Air 2005 RE Aer Lingus P.l.c. 10/11/05 53 Air 2006 EI Aero Asia International (private) Ltd. 10/11/05 532 Air 2007 E4 Aero California 10/11/05 78 Air 2008 JR Aero Costa Rica Acori S.a. 10/11/05 802 Air 2009 ML Aero Lloyd Flugreisen Gmbh And Co. Luftv 10/11/05 633 Air 2010 YP Aerocaribe 10/11/05 723 Air 2011 QA Aerochago Airlines S.a. 10/11/05 198 Air 2012 G3 Aeroejecutivo S.a. De C.v. 10/11/05 456 Air 2013 SX Aeroflot-russian International Airlines 10/11/05 555 Air 2014 SU Aerolineas Argentinas 10/11/05 44 Air 2015 AR Aerolineas Centrales De Colombia (aces) 10/03/10 137 Air 2016 VX REMOVE Aerolineas Dominicanas S.a. (dominair) 10/11/05 725 Air 2017 YU Aerolineas Internacionales S.a. De C.v. 10/11/05 440 Air 2018 N2 Aeromar C. Por. A. 10/11/05 926 Air 2019 BQ Aeromexico-aerovias De Mexico S.a. De C. 10/11/05 139 Air 2020 AM Aeromonterrey S.a. De C.v. 10/11/05 722 Air 2021 7M Aeroperlas 10/11/05 828 Air 2022 WL Aeroperu - Empresa De Transportes Aereos 10/11/05 210 Air 2023 PL Aeroservicios Ecuatorianos C.a. -

FEBRUARY 2020 $10.00 Aviationweek.Com/BCA

BUSINESS & COMMERCIAL AVIATION REGA TO THE RESCUE INSIDE OPS GROUP FALSE FAV FEBRUARY 2020 $10.00 Aviationweek.com/BCA Business & Commercial Aviation COVER STORY Rega to the Rescue ORITES An innovative Alpine operation with a global reach ALSO IN THIS ISSUE One Little Difference Inside Ops Group False Favorites FEBRUARY 2020 VOL. 116 NO. 2 Write Your Corporate Aircraft Use Policy Mollis Market Mover Digital Edition Copyright Notice The content contained in this digital edition (“Digital Material”), as well as its selection and arrangement, is owned by Informa. and its affiliated companies, licensors, and suppliers, and is protected by their respective copyright, trademark and other proprietary rights. Upon payment of the subscription price, if applicable, you are hereby authorized to view, download, copy, and print Digital Material solely for your own personal, non-commercial use, provided that by doing any of the foregoing, you acknowledge that (i) you do not and will not acquire any ownership rights of any kind in the Digital Material or any portion thereof, (ii) you must preserve all copyright and other proprietary notices included in any downloaded Digital Material, and (iii) you must comply in all respects with the use restrictions set forth below and in the Informa Privacy Policy and the Informa Terms of Use (the “Use Restrictions”), each of which is hereby incorporated by reference. Any use not in accordance with, and any failure to comply fully with, the Use Restrictions is expressly prohibited by law, and may result in severe civil and criminal penalties. Violators will be prosecuted to the maximum possible extent. -

Advisory Circular

U.S. Department Advisory of Transportation Federal Aviatlon Admlnlstration Circular Subject: FAA CERTIFICATED MAINTENANCE Date: 3 /6/g 7 AC No: 140-71 AGENCIES DIRECTORY Initiated by: AN-640 Change: 1. PURPOSE. This advisory circular (AC) transmits a consolidated directory of all certificated Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) repair stations and manufacturer’s maintenancefacilities. The repair stations and manufacturer’s maintenancefacilities were certificated as of January 2 1, 1997, under the authority of Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations (14 CFR) part 145, and the directories are current as of January 21, 1997. 2. CANCELLATION. This AC cancelsAC 140-7H, FAA Certificated Maintenance Agencies Directory, dated July 24, 1995. 3. DESCRIPTION. Appendix 1 is a listing of repair stations and appendix 2 is a listing of manufacturer’s maintenancefacilities, their addresses,ratings, and codes. 4. RATING LEGENDS, CODES, AND EXPLANATIONS. a. FAA certificated repair station rating codesare describedin detail in part -l45, and are: (1) AF-Airframe l-composite construction, small aircraft 2-composite construction, large aircraft 3-all metal construction, small aircraft 4-all metal construction, large aircraft (2) PP-Powerplant l--reciprocating engines,400 hp or less 2-reciprocating engines,more than 400 hp 3-turbine engines (3) PRP-Propeller l--fixed pitch and ground adjustablepropellers - wood, metal, or composite 2-all other propellers, by make (4) RAD-Radio l-communication equipment 2-navigation equipment 3-radar equipment AC 140-71 316197 (5) INS-Instrument l-mechanical 2--electrical 3-gyroscopic 44-electronic (6) AAC-Accessory l-mechanical 2--electrical 3-electronic (7) L--Limited AAC --accessories AF --airframe EE -emergency equipment FAB -aircraft fabric FL0 -floats INS -instruments LG -landing gear NDT -nondestructive testing OT --other PP -powerplant PRP -propellers RAD -radio equipment RB --rotor blades SS ---specialized (8) Ratings may be limited to a specific model of aircraft, powerplant, propeller, radio, instrument, accessory,or parts thereof.