PROCEEDINGS the 88Th Annual Meeting 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9 July 2018 21H20-22H30 Concert of Classical Music Programme Ruben Muradyan (Piano) Sergei Rachmaninov Melody Op

International Conference on New Frontiers in Physics ICNFP 2018 OAC, Kolymbari, Crete, 4-12.07.2018 9 July 2018 21h20-22h30 Concert of Classical Music Programme Ruben Muradyan (Piano) Sergei Rachmaninov Melody Op. 21, N 9, D major , Svetlana NOR (Violin) for cello and piano Vladimir Nor (cello), Ruben Muradyan (piano) Vladimir NOR (Cello) Pyotr Tchaikovsky Pezzo capriccioso, in B-minor, Op. 62, RUBEN MURADYAN (piano), RUSSIA for cello and piano (1882) Graduated from Moscow Conservatory, class of A.A. Nasedkina Vladimir Nor (cello), Ruben Muradyan (piano) and L.N. Vlasenko. Won K. Kana International Competition in Paris, got a diploma at the International Chamber Music Alexander Glazunov Competition in Finale Ligure (Italy). Professor at the Department Grand Adagio from "Raymonda" ballet of Piano and Organ, GMPI MM Ippolitov-Ivanov and a piano Svetlana Nor (violin), Ruben Muradyan (piano) teacher at Ippolitov-Ivanov Music school and at the Art School Piano "Spring". Giving concerts and master classes in Russia, Henri Vieuxtemps Armenia, Germany, France and Australia. Participating "Fantasy" on "The Nightingale" as the jury of various regional, national and international competitions. by Alyabyev, G minor, Op. 24 Svetlana Nor (violin), Ruben Muradyan (piano) SVETLANA NOR (violin), RUSSIA Graduated from Moscow Gnessin Secondary Music School Pyotr Tchaikovsky (violin class of Elena Koblyakova-Mazor) and from Gnessin Trio in A minor for piano, violin, Musical Pedagogical Institute (violin class of Miroslav Rusin and cello, Op. 50 (1882) and quartet class of Prof. Valentin Berlinsky). For twenty years is playing in Alyabiev Quartet together with her husband "In memory of a great artist" Vladimir Nor. -

Limited Edition 150 Th Anniversary of the Moscow Tchaikovsky Conservatory

Limited Edition 150 th Anniversary of the Moscow Tchaikovsky Conservatory This production is made possible by the sponsorship of BP Это издание стало возможным благодаря спонсорской помощи компании BP Richter Live in Moscow Conservatory 1951 – 1965 20 VOLUMES (27 CDs) INCLUDES PREVIOUSLY UNRELEASED RECORDINGS VOLUME 1 0184/0034 A D D MONO TT: 62.58 VOLUME 2 0184/0037A A D D MONO TT: 59.18 Sergey Rachmaninov (1873 – 1943) Ludwig van Beethoven (1770 – 1827) Twelve Preludes: Piano Concerto No. 1 in C major, op. 15 1 No. 2 in F sharp minor, op. 23 No. 1 3.43 1 1. Allegro con brio 16.40 2 No. 20 in A major, op. 32 No. 9 2.25 2 2. Largo 11.32 3 No. 21 in B minor, op. 32 No. 10 5.15 3 3. Rondo. Allegro scherzando 8.50 4 No. 23 in G sharp minor, op. 32 No. 12 2.10 Sergey Prokofiev (1891 – 1953) 5 No. 9 in A flat major, op. 23 No. 8 2.54 Piano Concerto No. 5 in G major, op. 55 6 No. 18 in F major, op. 32 No. 7 2.03 4 1. Allegro con brio 5.07 7 No. 12 in C major, op. 32 No. 1 1.12 5 2. Moderato ben accentuato 3.54 8 No. 13 in B flat minor, op. 32 No. 2 3.08 6 3. Toccata. Allegro con fuoco 1.52 9 No. 3 in B flat major, op. 23 No. 2 3.13 7 4. Larghetto 6.05 10 No. -

Borodin String Quartet

UNIVERSITY MUSICAL SOCIETY BORODIN STRING QUARTET Mikhail Kopelman, Violinist Dmitri Shebalin, Violist Andrei Abramenkov, Violinist Valentin Berlinsky, Cellist Tuesday Evening, February 18, 1992, at 8:00 Rackham Auditorium, Ann Arbor, Michigan PROGRAM Quartet in C minor, Op. 51, No. 1 .......... Brahms Allegro Romanze: poco adagio Allegretto molto moderate e comodo, un poco piu animate Finale: allegro IN TERMISSION Quartet No. 15 in E-flat minor, Op. 144 Shostakovich Elegy: adagio Serenade: adagio Intermezzo: adagio Nocturne: adagio Funeral March: adagio molto Epilogue: adagio, adagio molto The Borodin Quartet is represented by Mariedi Anders Artists Management, San Francisco. The University Musical Society is a member of Chamber Music America. Activities of the UMS are supported by the Michigan Council for Arts and Cultural Affairs and the National Endowment for the Arts. Twenty-sixth Concert of the 113th Season Twenty-ninth Annual Chamber Arts Series Program Notes Quartet in C minor, as an uneasy, sinister, shadowy one. The contrasting central trio section, Un poco piu Op. 51, No. 1 animate, is a folklike tune accompanied by JOHANNES BRAHMS (1833-1897) unusual sounds from the open strings of the he musical manner that Brahms second violin and viola. In the Allegro finale, adopted as a young man and the Brahms refers again to the Scherzo, but the skill that he showed when he was musical materials are most closely related to only 20 years old, led Schumann those that open the Quartet, and the whole to proclaim him "a musician is presented with a concentrated force that chosenT to give ideal expression to his times." recalls and balances the entire opening move Even when he was young, Brahms had found ment. -

World-Class Musicians Coming to Wimbledon 8 - 23 November 2014

Patrons: Lord Birkett ● Alfred Brendel ● Rivka Golani ● Ian Partridge ● Raphael Wallfisch “Re-defining the Best” World-class musicians coming to Wimbledon 8 - 23 November 2014 The Borodin Quartet playing Beethoven and Borodin, and Mozart with Michael Collins; An original Festival Production of Stravinsky’s Soldier’s Tale; Mozart and Beethoven Octets with London Winds; Anthems for Doomed Youth with Myrthen – Katherine Broderick, Clara Mouritz, Benjamin Hulett, Marcus Farnsworth, Joseph Middleton; ‘Five star’ Russian pianist Denis Kozhukhin; Viola Day with Lawrence Power and Christopher Wellington; International jazz with Paris Washboard; “thrilling” piano duo York2; “astonishing” Hungarian guitar duo The Katona Twins; Mozart ‘Exultate Jubilate’, Haydn ‘Nelson’ Mass with Academy Choir and Baroque Players, and Joanne Lunn; The SIXTEEN and Harry Christophers; Players of the Globe Theatre; Schubertiade with Kathron Sturrock and The Fibonacci Sequence. Wimbledon International Music Festival ng our com rti m are proud to continue to support the o u p n p it u y Wimbledon S International Music Festival Surveyors, Valuers & Estate Agents Surveyors, Valuers & Estate Agents 35 High Street, Wimbledon Village, London35 High Street, Wimbledon Village, London Wimbledo n SW19 5BY Telephone: 020 8947 9833 SW19 5BY Telephone: 020 8947 9833 RH_Wimbledon Music Festival_A5_03.indd 1 23/05/2014 15:31 Wimbledon International Music Festival 3 ‘Anthems for Doomed Youth’, a moving collection of songs drawn from Russia, Germany, Welcome to Wimbledon for the 2014 Festival France, Spain, Britain and America, will be presented by four superb young singers, and Joseph Middleton, piano. I was most encouraged to receive such warm audience feedback after last year’s Festival which has spurred me on to raise the bar and continue to bring world-class artists The brilliant guitar duo, the Katona Twins, will bring a programme of Spanish music interwoven to Wimbledon. -

Ambassador Auditorium Collection ARS.0043

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3q2nf194 No online items Guide to the Ambassador Auditorium Collection ARS.0043 Finding aid prepared by Frank Ferko and Anna Hunt Graves This collection has been processed under the auspices of the Council on Library and Information Resources with generous financial support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Archive of Recorded Sound Braun Music Center 541 Lasuen Mall Stanford University Stanford, California, 94305-3076 650-723-9312 [email protected] 2011 Guide to the Ambassador Auditorium ARS.0043 1 Collection ARS.0043 Title: Ambassador Auditorium Collection Identifier/Call Number: ARS.0043 Repository: Archive of Recorded Sound, Stanford University Libraries Stanford, California 94305-3076 Physical Description: 636containers of various sizes with multiple types of print materials, photographic materials, audio and video materials, realia, posters and original art work (682.05 linear feet). Date (inclusive): 1974-1995 Abstract: The Ambassador Auditorium Collection contains the files of the various organizational departments of the Ambassador Auditorium as well as audio and video recordings. The materials cover the entire time period of April 1974 through May 1995 when the Ambassador Auditorium was fully operational as an internationally recognized concert venue. The materials in this collection cover all aspects of concert production and presentation, including documentation of the concert artists and repertoire as well as many business documents, advertising, promotion and marketing files, correspondence, inter-office memos and negotiations with booking agents. The materials are widely varied and include concert program booklets, audio and video recordings, concert season planning materials, artist publicity materials, individual event files, posters, photographs, scrapbooks and original artwork used for publicity. -

Du 27 Mai Au 5 Juin Concoursmontreal.Ca Investir , Limaginaire

DU 27 MAI AU 5 JUIN CONCOURSMONTREAL.CA INVESTIR , LIMAGINAIRE DU CONSEIL DES ARTS ET des LETTRES DU QUÉBEC VIOLON 2019 VIOLIN MESSAGES Bienvenue au Concours musical international de Montréal GOUVERNEURE Édition violon 2019 GÉNÉRALE DU CANADA Avides de créer un évènement pour stimuler l’émergence de jeunes musiciens talentueux de partout au monde, le chanteur GOVERNOR GENERAL basse Joseph Rouleau et feu André Bourbeau ont eu l’idée de OF CANADA fonder le Concours musical international de Montréal (CMIM). Ce fut le début d’une grande aventure musicale ! Le CMIM offre un contact privilégié avec une musique de très haute qualité. Alternant sa programmation d’une année à l’autre entre le chant, le violon et le piano, il fait rayonner la musique classique et la met à la portée de tous. Depuis la première édition au printemps 2002, des milliers de candidats ont participé au concours pour le plus grand plaisir du public montréalais et des nombreux mélomanes qui assistent à la diffusion des récitals en direct d’un bout à l’autre de la planète. Cette année ne sera pas en reste. Les 24 concurrents sélection- nés parmi les jeunes violonistes les plus prometteurs au monde SGT JOHANIE MAHEU seront évalués par un jury international présidé par Zarin Mehta. Lors de la finale, ils seront acompagnés par l’Orchestre sympho- nique de Montréal, sous la direction d’Alexander Shelley, que je connais du Centre national des Arts d’Ottawa et que j’admire beaucoup. Vous serez éblouis ! Bonne édition 2019 ! Son Excellence la très honorable Her Excellency the Right Honourable JULIE PAYETTE C.C., C.M.M., C.O.M., C.Q., C.D. -

TOCC0327DIGIBKLT.Pdf

VISSARION SHEBALIN: COMPLETE MUSIC FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO by Paul Conway Vissarion Shebalin was one of the foremost composers and teachers in the Soviet Union. Dmitri Shostakovich held him in the highest esteem; he kept a portrait of his slightly older friend and colleague hanging on his wall and wrote this heartfelt obituary: Shebalin was an outstanding man. His kindness, honesty and absolute adherence to principle always amazed me. His enormous talent and great mastery immediately earned him burning love and authority with friends and musical community.1 Recent recordings have rekindled interest from listeners and critics alike in the works of this key fgure in mid-twentieth-century Soviet music. Vissarion Yakovlevich Shebalin was born in Omsk, the capital of Siberia, on 11 June 1902. His parents, both teachers, were utterly devoted to music. When he was eight years old, he began to learn the piano. By the age of ten he was a student in the piano class of the Omsk Division of the Russian Musical Society. Here he developed a love of composition. In 1919 he completed his studies at middle school and entered the Institute of Agriculture – the only local university at that time. When a music college opened in Omsk in 1921, Shebalin joined immediately, studying theory and composition with Mikhail Nevitov, a former pupil of Reinhold Glière. In 1923 he was accepted into Nikolai Myaskovsky’s composition class at the Moscow Conservatoire. His frst pieces, consisting of some romances and a string quartet, received favourable reviews in the press. Weekly evening concerts organised by the Association of 1 ‘To the Memory of a Friend’, in Valeria Razheava (ed.), Shebalin: Life and Creativity, Molodaya Gvardiya, Moscow, 2003, pp. -

Seattle-Symphony-May-2017-Encore

MAY 2017 CELEBRATE ASIA BROADWAY ROCKS WITH THE SEATTLE MEN’ S CHORUS LOOKING AHEAD: RAVEL’ S MAGICAL OPERA Sophistication without compromise. Satisfaction without delay. Work with Coldwell Luxury lives here. Banker Bain to find a home that completes your dreams, anywhere in the world, and quenches your desire for the very best. Coldwell Banker Bain Global Luxury. ColdwellBankerBain.com/GlobalLuxury It’s what we do. SeattleSymphony_LuxuryLivesHere.indd 1 4/18/2017 11:20:03 AM Encore spread.indd 1 4/18/17 1:54 PM Sophistication without compromise. Satisfaction without delay. Work with Coldwell Luxury lives here. Banker Bain to find a home that completes your dreams, anywhere in the world, and quenches your desire for the very best. Coldwell Banker Bain Global Luxury. ColdwellBankerBain.com/GlobalLuxury It’s what we do. SeattleSymphony_LuxuryLivesHere.indd 1 4/18/2017 11:20:03 AM Encore spread.indd 1 4/18/17 1:54 PM CONTENTS SUBSCRIPTIONS NOW ON SALE SINGLE TICKETS ON SALE AUGUST 1 WORLD DANCE SERIES BANDALOOP Lizt Alfonso Dance Cuba Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company Cloud Gate Dance Theatre of Taiwan Hubbard Street Dance Chicago Complexions Contemporary Ballet WORLD MUSIC & THEATER SERIES Habib Koité Third Coast Percussion Martha Redbone: Bone Hill - The Concert Feathers of Fire: A Persian Epic Diego El Cigala INTERNATIONAL CHAMBER MUSIC SERIES Juilliard String Quartet Montrose Trio Takács Quartet with special guest Erika Eckert Danish String Quartet Jerusalem Quartet Calidore String Quartet with David Finckel & Wu Han PRESIDENT'S PIANO -

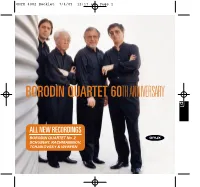

Borodin Quartet 60Th Anniversary

ONYX 4002 Booklet 7/4/05 12:17 am Page 1 BORODIN QUARTET 60TH ANNIVERSARY p1 ONYX 4002 Booklet 7/4/05 12:17 am Page 2 ALEXANDER BORODIN (1833-1887) String Quartet No. 2 in D Major • ré majeur • D-Dur . re maggiore 1 Allegro moderato 8.45 2 Scherzo: Allegro 5.10 3 Notturno: Andante 8.37 4 Finale: Andante-Vivace 7.14 PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY (1840-1893) 5 Andante cantabile (from String Quartet No. 1) 7.22 SERGEI RACHMANINOV (1873-1943) 6 Romance 6.13 FRANZ SCHUBERT (1797-1828) 7 Quartettsatz 9.37 ANTON WEBERN (1883-1945) 8 Langsamer Satz 11.08 ALEXANDER BORODIN (1833-1887) 9 Serenata alla Spagnola 2.18 p2 Total Time 66.28 BORODIN QUARTET Rubén Aharonian (violin) Andrei Abramenkov (violin) Igor Naidin (viola) Valentin Berlinsky (cello) ONYX 4002 Booklet 7/4/05 12:17 am Page 3 The Borodin Quartet at 60 Whenever the Borodin Quartet notches up an anniversary, so too does its cellist (and so in 2005, while the ensemble marks 60 years as what the Russians call ‘the Quartet named Borodin’, we also toast Valentin Berlinsky on his 80th birthday). This is very much as it should be: “Valentin” Berlinsky is both patriarch and soul of the quartet. As anchorman throughout of the group which turned to the Soviet authorities for its present name in 1955, Berlinsky has lived through many changes of personnel in the early years, guided the quartet through difficult times at home and on countless tours, and still imparts his ineffably cultured tones to its latest incarnation. -

Proquest Dissertations

M u Ottawa L'Unh-wsiie eanadienne Canada's university FACULTE DES ETUDES SUPERIEURES IfisSJ FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND ET POSTOCTORALES U Ottawa POSDOCTORAL STUDIES L'Universite canadienne Canada's university Jada Watson AUTEUR DE LA THESE /AUTHOR OF THESIS M.A. (Musicology) GRADE/DEGREE Department of Music lATJULfEJ^LTbliP^ Aspects of the "Jewish" Folk Idiom in Dmitri Shostakovich's String Quartet No. 4, OP.83 (1949) TITREDE LA THESE/TITLE OF THESIS Phillip Murray Dineen _________________^ Douglas Clayton _______________ __^ EXAMINATEURS (EXAMINATRICES) DE LA THESE / THESIS EXAMINERS Lori Burns Roxane Prevost Gary W, Slater Le Doyen de la Faculte des etudes superieures et postdoctorales / Dean of the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies ASPECTS OF THE "JEWISH" FOLK IDIOM IN DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH'S STRING QUARTET NO. 4, OP. 83 (1949) BY JADA WATSON Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master's of Arts degree in Musicology Department of Music Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Jada Watson, Ottawa, Canada, 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-48520-0 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-48520-0 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant -

Mozart • Schumann • Schubert

International Conference on New Frontiers in Physics ICNFP 2017 OAC, Kolymbari, Crete, 17-29.08.2017 Classical Music Concert VLADIMIR NOR (cello), RUSSIA Got music education in Rostov-on-Don, from the famous cellist Alexander Volpov (GB). Continued his studies inMoscow at the Russian Academy of Music in the class ofProf. Vladimir Tonkha (cello) and legendary cellist of Borodin Quartet, Prof. Valentin Berlin (quartet class). For twenty years is playing in Alyabiev Quartet. Got First Prize of the All-Russian competition, Honored Artist of the Russian Federation. SVETLANA NOR (violin), RUSSIA Graduated from Moscow Gnessin Secondary Music School (violin class of Elena Koblyakova-Mazor) and from Gnessin Musical Pedagogical Institute (violin class of Miroslav Rusin and quartet class of Prof. Valentin Berlinsky). For twenty years is playing in Alyabiev Quartet together with her husband Vladimir Nor. Honored Artist of the Russian Federation. • • RUBEN MURADYAN (piano), RUSSIA Mozart Schumann Schubert Graduated from Moscow Conservatory, class of AA Nasedkina and LN Vlasenko. Won K. Kana International Competition in Paris, got a diploma at the International Chamber Music Competition in Finale Ligure (Italy). Professor at the Department of Piano and Organ, GMPI MM Ippolitov-Ivanov and a piano teacher at Ippoli- tov-Ivanov Music school and at the Art School Piano "Spring". Giving concerts and 21 August 2017, 21:10-22:30 master classes in Russia, Armenia, Germany, France and Australia. Participating as the jury of various regional, national and international competitions. Kolymbari, OAC Mikhail NOR Programme (Tenor) Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) Violin sonata in A major, К.526 1. Molto allegro 2. -

Modern Music Which Sounds Like Music

“I consider him to be a genius […]. I do think that one day people will come to know that two great Russian composers bore the same name…” — Mstislav Rostropovich Modern music which sounds like Music The composer-innovator who enriched the tradition of Russian music Boris Tchaikovsky (1925-1996) was an outstanding Russian composer of the second half of the 20th century, whose importance is becoming more and more clear in the last few years. Easily using any super- advanced tools of composing, the composer primarily strived for ultimate simplicity and expression of the key components of musical speech. The gift of deep philosophical and poetical understanding of the world enabled him to remain himself at every stage of his creative evolution. In fact, the composer did not leave behind a single failed opus. Due to the efforts of The Boris Tchaikovsky Society, almost all of the com- poser’s major works have become available on the CD recordings, issued by different labels. Among the most important CDs: Sebastopol Symphony Violin Concerto Music for Orchestra Odense SO/Edward Serov The Wind of Siberia Victor Pikaizen (violin) Moscow Radio SO “It certainly is unlike any other violin concerto Vladimir Fedosseyev I’ve ever heard. In such rare works we are taken to an inner world that we simply could never have CD of the Year imagined existed, and yet it is presented to us with (Svenska Dagbladet, 2005) such particularity and vividness that it seems un- deniably real. The performance conveys absolute Northern Flowers “The music by Boris Tchaikovsky