Ippt 2020 Kent Full Programme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Seven Ages of Musical Theatre: the Life Cycle of the Child Performer

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON The Seven Ages of Musical Theatre: The life cycle of the child performer by Lyndsay Barnbrook A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Humanities Faculty School of Music April 2016 \A person's a person, no matter how small." Dr. Seuss UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON Abstract Humanities Faculty School of Music Doctor of Philosophy The Seven Ages of Musical Theatre: The life cycle of the child performer by Lyndsay Barnbrook The purpose of the research reported here is to explore the part played by children in musical theatre. It aims to do this on two levels. It presents, for the first time, an historical analysis of involvement of children in theatre from its earliest beginnings to the current date. It is clear from this analysis that the role children played in the evolution of theatre has been both substantial and influential, with evidence of a number of recurring themes. Children have invariably made strong contributions in terms of music, dance and spectacle, and have been especially prominent in musical comedy. Playwrights have exploited precocity for comedic purposes, innocence to deliver difficult political messages in a way that is deemed acceptable by theatre audiences, and youth, recognising the emotional leverage to be obtained by appealing to more primitive instincts, notably sentimentality and, more contentiously, prurience. Every age has had its child prodigies and it is they who tend to make the headlines. However the influence of educators and entrepreneurs, artistically and commercially, is often underestimated. Although figures such as Wescott, Henslowe and Harris have been recognised by historians, some of the more recent architects of musical theatre, like Noreen Bush, are largely unheard of outside the theatre community. -

2019-20 Drama School V. University Choosing the Right Path for Your Future out of the Spotlight Speak the Speech, Training and Careers I Pray You

STUDENT GUIDE TO www.dramaandtheatre.co.uk/SGDE 2019-20 Drama School v. university Choosing the right path for your future Out of the spotlight Speak the speech, Training and careers I pray you... beyond performance Choosing and preparing monologues Comprehensive advice for those applying to study or train in any aspect of the performing arts 001_SGDE_COVER [APPROVED].indd 1 23/07/2019 13:16 Apply for BA (Hons) and Foundation Courses at ArtsEd! Exceptional triple threat training. Revolutionary stage and screen Acting training. ArtsEd was ranked the top Igniting your drama school for overall student satisfaction in the 2019 National Student Survey with over 90% of students passion for happy with their training. Find out more: www.artsed.co.uk performance [email protected] @ArtsEdLondon 0_SGDE_2019/20.indd 2 05/08/2019 12:48 Welcome Extra online STUDENT GUIDE TO material The Student Guide to Drama Education is also available to 2019-20 read free online, where you will elcome to the Student Guide to Drama Education – a guide designed to off er fi nd links to extra comprehensive advice to anyone thinking of applying to study or train in any aspect of pages of course- Wthe performing arts. listings. Visit www. Everything in this guide has been written straight ‘from the horse’s mouth’ dramaandtheatre. – students and graduates of all the major disciplines share what it’s like to study their courses; teaching staff from world-class Higher Education co.uk from institutions tell you what you need to know about applying for their October 2019. courses; and working professionals in the industry off er career tips for those all-important early years in and out of training. -

Federation of Drama Schools Agreement

INFORMATION FOR STUDENTS BA Acting or BA Stage & Production Management at East 15 Acting School offer holders only. The following does not apply to applicants holding offers on any other East 15 or University of Essex course. Applicants may only accept a place at one Federation of Drama Schools member school at any one time. If you have already accepted a place and subsequently change your mind and want to accept a later offer, you must cancel your acceptance of the previous place accepted, by writing to the relevant school. Cancellations can be received up to and including 1st July. After 15th July no Federation of Drama Schools member school may make an offer to a candidate who has been offered and accepted a place at another Federation of Drama Schools member school. It is absolutely essential that you do not accept and hold more than one offer of a place at any one time, but you are free to attend auditions/interviews at other schools and may change your mind as often as you wish (provided you decline, in writing the previous offer) up to the closing date given above. If you are offered a place on a course at a Federation of Drama Schools member school, you may, on accepting the offer, be asked for a deposit. Federation of Drama Schools strongly recommends that you make sure you understand each school’s current policy on deposits before entering into an agreement that could have financial implications for you FEDERATION OF DRAMA SCHOOLS SCHOOL’S MEMBERS ARE: ALRA – Academy of Life and Recorded Arts Arts Educational Schools London -

A Time of Challenge 2021 a Time of Challenge 2021

COVID-19 PANDEMIC Accredited Professional Schools offering Vocational Training in Dance, Drama and Musical Theatre A Time of Challenge 2021 A Time of Challenge 2021 Contents Introduction This report is prepared on behalf of CDMT Accredited schools; institutions that together make an enormous contribution to the Introduction 03 sustainability and international profile of the UK creative industries, and with whom we share a mission for advancing outstanding The Accredited Vocational Training Sector 04 artistic performance. These professional schools and colleges have significant concerns The Challenges 06 about the support needed to restart the sector for business as we emerge from lockdown. The financial impacts on them, and their The Recommendations 10 networks, due to the Covid-19 conditions are of a significant order. We ask that the authorities address more directly the needs, both professional and financial, of these training establishments. Whatever decisions are made for the wider industry, including for theatres and other performance venues, consideration must also be made of the assistance needed to secure the existing ‘pipeline’ of highly trained future professionals on which the sector relies. Prepared by the Council for Dance, Drama and Musical Theatre First edition July 2020 Second edition March 2021 CDMT produces the annual UK Guide to Professional Training, Education and Assessment in the Performing Arts. CDMT Old Brewer’s Yard Covent Garden 0207 240 5703 Workman Robert 17-19 Neal Street London WC2H 9UY [email protected] 2 cdmt.org.uk -

Federation of Drama Schools Response to Covid-19 Pandemic

Federation of Drama Schools Response to Covid-19 Pandemic The Federation of Drama Schools (FDS) represents twenty of the United Kingdom’s leading providers of professional conservatoire performance and technical training. As a community of artists, creators, and innovators, we have come together during the Covid-19 pandemic to provide support, guidance, reassurance and inspiration to our students, staff, graduates, alumni, colleagues and friends within the creative industries. The scale and impact of the coronavirus crisis has been significant upon our sector and related industries, which holds dear the ethos of embodied practice and the necessity of physical interaction in pursuit of understanding and celebrating the human condition. Whilst we are unable to determine the duration of the outbreak we are united in meeting the societal and educational challenges we collectively face with a shared determination and limitless imagination. Each of the FDS member institutions appreciates the scale and complexity of the challenges presented as a consequence of having to deliver conservatoire training programmes via online platforms. However, we also appreciate that we have no option in the present circumstances and therefore it is incumbent upon us to provide confidence, leadership and hope. Each school recognises that whilst the learning experience will be different, we remain committed to ensuring that excellence and high standards of professional practice are maintained in pursuit of continuing to deliver world leading performance and technical training programmes despite the challenges. All schools have had to migrate audition and recruitment processes online at very short notice. We recognise the limitations of this process, however, we are all committed to ensuring that access, opportunity and experience will remain robust, rigorous and fair. -

FURTHER EDUCATION AWARDS 2014/15 Date of Issue: 16 May 2014

Circular Number: Subject: FE 05/14 FURTHER EDUCATION AWARDS 2014/15 Date of Issue: 16 May 2014 Target Audience: Status of Contents: Information • Principals /Directors of FE Colleges • Chairs of Governing Bodies • Student Finance NI - WELB • FE College Finance • Colleges Northern Ireland • College Student Support Officers / Hardship Fund Co-ordinators Summary of Contents: Related Documents: This Circular provides information and guidance on FE 08/07 Further Education Awards. Education [Student Support] Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2012. Superseded Documents: FE 05/13 Expiry Date: N/A Enquiries: DEL Website: www.delni.gov.uk Any enquiries about the contents of this Circular should be addressed to: Tel: 028 90 257547 Further Education Finance Branch Fax: 028 90 257528 Department for Employment & Learning Room 206 Email:[email protected] Adelaide House 39 – 49 Adelaide Street BELFAST BT2 8FD - 1 - Introduction FURTHER EDUCATION AWARDS Further Education Awards are administered by the Western Education and Library Board (WELB) on behalf of the Department. Funding of Further Education Awards are made subject to the conditions specified in this circular and subject to a limited budget targeted at Further Education courses for which there is no statutory support. As a student can only receive one form of publicly funded financial support, students who are planning to, or have already submitted applications and/or are in receipt of any other publicly funded financial support (e.g. EMA) are not eligible to apply for a Further Education Award. Receiving more than one form of Government funding may be construed as fraud and dealt with accordingly. It is the responsibility of the applying student to declare all other publicly funded financial support in their application, failure to do so may result in legal action to recover fraudulent funding and withdrawal of future support. -

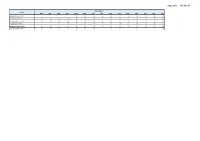

Appendix - 2019/6192

Appendix - 2019/6192 PM2.5 (µg/m3) Region 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 Background Inner London 16 16 16 15 15 14 13 13 13 12 n/a Roadside Inner London 20 19 19 19 18 18 18 17 17 17 16 16 15 15 n/a Background Outer London 14 14 14 14 14 14 14 14 13 13 13 12 12 11 n/a Roadside Outer London 15 16 17 17 18 17 17 16 15 14 13 12 n/a Background Greater London 14 14 14 14 15 15 15 14 14 14 13 13 12 12 n/a Roadside Greater London 20 19 17 18 18 18 18 17 17 16 16 15 14 13 n/a Appendix - 2019/6194 NO2 (µg/m3) Region 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 Background Inner London 44 44 43 42 42 41 40 39 39 38 37 36 35 34 n/a Roadside Inner London 68 70 71 72 73 73 73 72 71 71 70 69 65 61 n/a Background Outer London 36 35 35 34 34 34 33 33 32 32 32 31 31 30 n/a Roadside Outer London 50 50 51 51 51 51 50 49 48 47 46 45 44 44 n/a Background Greater London 40 40 39 38 38 38 37 36 36 35 35 34 33 32 n/a Roadside Greater London 59 60 61 62 62 62 62 61 60 59 58 57 55 53 n/a Appendix - 2019/6320 360 GSP College London A B C School of English Abbey Road Institute ABI College Abis Resources Academy Of Contemporary Music Accent International Access Creative College London Acorn House College Al Rawda Albemarle College Alexandra Park School Alleyn's School Alpha Building Services And Engineering Limited ALRA Altamira Training Academy Amity College Amity University [IN] London Andy Davidson College Anglia Ruskin University Anglia Ruskin University - London ANGLO EUROPEAN SCHOOL Arcadia -

PDF Copy Here

acting…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...................... page 4 screen.……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. page 12 writing……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. page 17 shakespeare…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… page 18 voice………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. page 19 recorded voice……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. page 21 physical………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. page 23 casting……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. page 25 musical…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… page 27 career…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. page 28 sony……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. page 32 member career development………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… page 33 open courses: non-member workshops…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. page 34 tristan bates theatre………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. page 35 We are thrilled to partner with Methuen for the January-March season. Methuen have over 2,000 titles available for theatre-goers, students, scholars, practitioners, actors and those wishing to pursue a career in the theatre industry. These workshops will be led by theatre practitioners who have published works with Methuen. We are delighted to have these industry leaders sharing their knowledge and experience across a range -

Annual Review 2012 Download Review

The Andrew Lloyd Webber Foundation The Andrew Lloyd Webber Foundation ANNUAL REVIEW 2012 WWW.ANDREWLLOYDWEBBERFOUNDATION.COM § Andrew Lloyd Webber at the Royal Welsh College of Music & Drama ABOUT THE FOUNDATION The Foundation was founded by Andrew Lloyd Webber in 1992 to promote the arts, culture and heritage for the public benefit. Since inception, Andrew has been the principle provider of funding for all its charitable activities. The Foundation believes that in order to retain vibrancy in the arts, it is imperative for young artists of all backgrounds and abilities to be nurtured and encouraged. The focus during 2012 has been to support projects that provide high quality training, career development, professional guidance, apprenticeship and work placement schemes across a wide range of arts, culture and heritage projects. The projects have demonstrated their ability to make a real difference to improve the quality of life both for individuals and within local communities. The Trustees have been delighted that the Foundation’s support has in turn encouraged other individuals, organisations and public bodies to support these and similar projects this year and hope that this trend will continue for the future. The Andrew Lloyd Webber Foundation § THE ANDREW LLOYD WEBBER FOUNDATION | GRANT RECIPIENTS 2012 SCHOLARSHIPS The Andrew Lloyd Webber Foundation funds 10 new Musical Theatre scholarships each year at renowned musical theatre colleges throughout the UK. The Scholarships are awarded by the colleges as part of the selection process -

List of CDS Drama Schools.Pdf

The Conference of Drama Schools www.drama.ac.uk CDS Guide to Professional Training in Drama & Technical Theatre 2007 in association with THE CONFERENCE OF DRAMA SCHOOLS CDS Guide to Professional Training in Drama and Technical Theatre 2007 For additional copies of this Guide Sponsor of The Guide please contact French’s Theatre 1 Bookshop: Write to: French’s Theatre Bookshop, 52 Fitzroy Street, London W1T 5JR Tel: 020 7255 4300 Email: [email protected] www.samuelfrench-london.co.uk Founded 1927 The internationally famous casting directory To contact CDS please write to: www.spotlightcd.com +44 (0)20 7437 7631 Executive Secretary CDS Limited PO Box 34252 London NW5 1XJ Supported by For the latest information on CDS schools, French’s Theatre Learning and The National Association of a downloadable version of this guide and a Bookshop Skills Council Careers and Guidance Teachers serchable database of courses please see: www.drama.ac.uk © The Conference of Drama Schools Ltd 2006. All rights reserved. Except as otherwise permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission of the copyright holders. The contents and advertisements in this book are compiled and published in good faith. The Publisher cannot accept any liability for any claim howsoever arising, including as a result of any person acting or refraining Design, print & marketing from acting on the contents, whether any resultant loss is direct or indirect. The Conference of Drama Schools is a company limited by guarantee, registered in England, Registered address: The Spotlight, 7 Leicester Place, London WC2H 7RJ Company no. -

Tier 4) Date: 28-June-2018

REGISTER OF SPONSORS (Tier 4) Date: 28-June-2018 Register of Licensed Sponsors This is a list of institutions licensed to sponsor migrants under Tier 4 of the points-based system. It shows the sponsor's name, their primary location, their sponsor type, the location of any additional centres being operated (including centres which have been recognised by the Home Office as being embedded colleges), the rating of their licence against each sub tier(s), the sub tier(s) they are licensed for, and whether the sponsor is subject to an action plan to help ensure immigration compliance. Legacy sponsors cannot sponsor any new students. For further information about Tier 4 of the points-based system, please refer to the Tier 4 Guidance for Sponsors on the GOV.UK website. No. of Sponsors Licensed under Tier 4: 1,228 Sponsor Name Town/City Sponsor Type Additional Status Sub Tier Immigration Locations Compliance Abberley Hall Worcester Independent school Tier 4 Sponsor Tier 4 (Child) Abbey College Cambridge Cambridge Independent school Tier 4 Sponsor Tier 4 General Tier 4 Sponsor Tier 4 (Child) Abbey College Manchester Manchester Independent school Tier 4 Sponsor Tier 4 General Tier 4 Sponsor Tier 4 (Child) Abbots Bromley School Nr. Rugeley Independent school Tier 4 Sponsor Tier 4 General Tier 4 Sponsor Tier 4 (Child) Abbotsholme School Uttoxeter Independent school Tier 4 Sponsor Tier 4 General Tier 4 Sponsor Tier 4 (Child) Abbotsholme School UTTOXETER Independent school Probationary Tier 4 (Child) Sponsor Probationary Tier 4 General Sponsor Abercorn -

Getting Into Drama School After Your Sixth Form

Education Advisers Ltd UK Private School Consultancy service Choosing the right private school for your child can be an overwhelming and nerve-racking experience for the whole family. It is, without doubt, one of the most important decisions you will make for your child. Your child’s school will play a huge role in forming positive and resilient characteristics, developing talents, building confidence, and preparing them to face our ever-changing world. It is therefore essential you are confident you have fully investigated all suitable options, and are sending your child to a school in which they will thrive both academically and emotionally. Since 2004 Education Advisers Ltd has supported over a thousand British and international families in identifying and gaining entry to the best- fitting schools. Our commitment is to provide completely impartial advice, and to ensure you and your child are fully informed and prepared from the very beginning until they are happily enrolled in a school. The process of identifying and applying to schools need not be stressful. Managed with expertise and empathy, it should be the first step of an exciting and life-changing journey for your family. We produce these guides to provide parents with what our experience tells us are the most important considerations when navigating your child’s education. We hope you find this guide on How to Choose the Right IB school a useful resource with which to begin your journey. We also invite you to request a free initial 20-minute phone consultation to explain your objectives and learn more about the most suitable strategy for your individual circumstances.