Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nominations of Hon. David C. Williams, Hon. Robert M

S. Hrg. 115–450 NOMINATIONS OF HON. DAVID C. WILLIAMS, HON. ROBERT M. DUNCAN, AND CALVIN R. TUCKER TO BE GOVERNORS, U.S. POSTAL SERVICE HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY AND GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION NOMINATIONS OF THE HONORABLE DAVID C. WILLIAMS, THE HONORABLE ROBERT M. DUNCAN, AND CALVIN R. TUCKER TO BE GOVERNORS, U.S. POSTAL SERVICE APRIL 18, 2018 Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.Govinfo.gov/ Printed for the use of the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 32–453 PDF WASHINGTON : 2019 COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY AND GOVERNMENTAL AFFAIRS RON JOHNSON, Wisconsin, Chairman JOHN MCCAIN, Arizona CLAIRE MCCASKILL, Missouri ROB PORTMAN, Ohio THOMAS R. CARPER, Delaware RAND PAUL, Kentucky HEIDI HEITKAMP, North Dakota JAMES LANKFORD, Oklahoma GARY C. PETERS, Michigan MICHAEL B. ENZI, Wyoming MAGGIE HASSAN, New Hampshire JOHN HOEVEN, North Dakota KAMALA D. HARRIS, California STEVE DAINES, Montana DOUG JONES, Alabama CHRISTOPHER R. HIXON, Staff Director GABRIELLE D’ADAMO SINGER, Chief Counsel JENNIFER L. SELDE, Professional Staff Member MARGARET E. DAUM, Minority Staff Director DONALD K. SHERMAN, Minority Senior Advisor LAURA W. KILBRIDE, Chief Clerk BONNI E. DINERSTEIN, Hearing Clerk (II) C O N T E N T S Opening statements: Page Senator Johnson ............................................................................................... 1 Senator McCaskill ........................................................................................... -

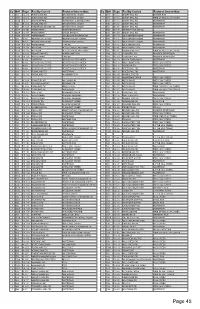

Bridge Index

Co Br# Page Facility Carried Featured Intersedtion Co Br# Page Facility Carried Featured Intersedtion 1 001 12 2-G RISING SUN RD BRANDYWINE CREEK 1 087 9 10-C SNUFF MILL RD BURRIS RUN 1 001A 12 2-G RISING SUN RD BRANDYWINE CREEK 1 088 9 10-C SNUFF MILL RD TRIB OF RED CLAY CREEK 1 001B 12 2-F KENNETT PIKE WATERWAY & ABANDON RR 1 089 9 10-C SNUFF MILL RD. WATERWAY 1 002 9 12-G ROCKLAND RD BRANDYWINE CREEK 1 090 9 10-C SNUFF MILL RD. WATERWAY 1 003 9 11-G THOMPSON BRIDGE RD BRANDYWINE CREEK 1 091 9 10-C SNUFF MILL RD. WATERWAY 1 004P 13 3-B PEDESTRIAN NORTHEAST BLVD 1 092 9 11-E KENNET PIKE (DE 52) 1 006P 12 4-G PEDESTRIAN UNION STREET 1 093 9 10-D SNUFF MILL RD WATERWAY 1 007P 11 8-H PEDESTRIAN OGLETOWN STANTON RD 1 096 9 11-D OLD KENNETT ROAD WATERWAY 1 008 9 9-G BEAVER VALLEY RD. BEAVER VALLEY CREEK 1 097 9 11-C OLD KENNETT ROAD WATERWAY 1 009 9 9-G SMITHS BRIDGE RD BRANDYWINE CREEK 1 098 9 11-C OLD KENNETT ROAD WATERWAY 1 010P 10 12-F PEDESTRIAN I 495 NB 1 099 9 11-C OLD KENNETT RD WATERWAY 1 011N 12 1-H SR 141NB RD 232, ROCKLAND ROAD 1 100 9 10-C OLD KENNETT RD. WATERWAY 1 011S 12 1-H SR 141SB RD 232, ROCKLAND ROAD 1 105 9 12-C GRAVES MILL RD TRIB OF RED CLAY CREEK 1 012 9 10-H WOODLAWN RD. -

"Delaware Is Not a State": Are We Witnessing Jurisdictional Competition in Bankruptcy?

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 55 Issue 6 Issue 6 - Symposium: Convergence on Delaware: Corporate Bankruptcy and Corporate Article 6 Governance 11-2002 "Delaware is Not a State": Are We Witnessing Jurisdictional Competition in Bankruptcy? Marcus Cole Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Bankruptcy Law Commons Recommended Citation Marcus Cole, "Delaware is Not a State": Are We Witnessing Jurisdictional Competition in Bankruptcy?, 55 Vanderbilt Law Review 1845 (2003) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol55/iss6/6 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "Delaware is Not a State": Are We Witnessing Jurisdictional Competition in Bankruptcy? Marcus Cole* I. THE RISE OF DELAWARE BANKRUPTCY ............................... 1850 II. LAWYERS' EXPLANATIONS FOR CHOOSING DELAWARE ....... 1859 A. The Factorsfor Lawyers ......................................... 1859 1. Predictability ............................................... 1859 2 . S p eed ............................................................ 1860 3. (The Absence of) "Real Law" .................1861 4. Sophistication of the Judges ....................... 1863 5. Responsiveness and Availability of the Ju dges .......................................................... 1864 6. Attorneys' -

FINAL THOUGHTS with CHRIS BASON William Kurt Foreman and Michael J. Quaranta Take Charge of Delaware's Two Largest Business Grou

5Q with Thomas J. Hanna May 1, 2018 | Vol. 5 • No. 9 | DelawareBusinessTimes.com | $2.00 8 2018 SMALL BUSINESS WINNERS 14 NEW ERA FOR DOWNTOWN SMYRNA 20 SHARED MISSION William Kurt Foreman and Michael J. Quaranta take FILLING VACANCIES charge of Delaware's two largest business groups | 11-13 IN DOVER 22 FINAL THOUGHTS WITH CHRIS BASON Director, Delaware Center For Inland Bays 35 2 | May 1, 2018 DELAWARE BUSINESS TIMES DelawareBusinessTimes.com Brian Simmons and Steve Masterson CO-FOUNDERS WASTE MASTERS SOLUTIONS An environment for growth. Understanding what’s important. When Steve Masterson and Brian Simmons founded Waste Masters Solutions, there was never a question of which bank they would choose. M&T Bank’s service-oriented approach was ideal for their environmental solutions company. Since 2010, our guidance and financing resources have supported their goals for expansion. And Waste Masters Solutions is well on its way, now working with large-scale clients, including two major sports franchises across the tri-state area. To learn how M&T can help your business, call Mark Hutton at 302-651-1204 or visit mtb.com/commercial. DEPOSITORY AND LENDING SOLUTIONS | TREASURY MANAGEMENT | MERCHANT SERVICES | COMMERCIAL CARD Equal Housing Lender. ©2018 M&T Bank. Member FDIC. 16773 Delaware Business Times / 10”w x 13”h DelawareBusinessTimes.com DELAWARE BUSINESS TIMES May 1, 2018 | 3 FIRST LOOK Founded 2014 A Biweekly Newspaper Serving Sen. Coons’ star — like his mentor Joe Biden’s — clearly is in ascension Delaware’s Business Community Vol. 5, No. 9 dated May 1, 2018 U.S. Sen. Chris Coons’s committee Keep in mind that Delaware is a state that sent a liberal © Copyright 2017 by Today Media, All Rights Reserved. -

Town of Little Creek, Delaware Comprehensive Plan

TownTown ofof LittleLittle Creek,Creek, DelawareDelaware ComprehensiveComprehensive PlanPlan July 2006 Prepared by The Town of Little Creek Planning Commission With assistance from the Delaware Office of State Planning Coordination Little Creek, Delaware Comprehensive Plan Adopted by the Little Creek Planning Commission In December 2005; and by the Little Creek Town Council July 2006 Prepared by: The Town of Little Creek Planning Commission With assistance from the: Delaware Office of State Planning Coordination August 28, 2006 The Honorable Harry E. Marvel, Sr. Mayor, Town of Little Creek P.O. Box 298 Little Creek, DE 19961 RE: Certification of the Town of Little Creek Comprehensive Plan Dear Mayor Marvel: I am pleased to inform the Town that as of August 7, 2006 per the recommendation of the Office of State Planning Coordination, the comprehensive plan for the Town of Little Creek is hereby certified provided no major changes are enacted. The certification signifies that the comprehensive plan is currently in compliance with State Strategies. I would like to take this opportunity to thank the Town of Little Creek for working with the State to incorporate our recommendations into the plan before adoption. My staff and I look forward to working with the Town to accomplish the goals set forth in your plan. Congratulations on your certification! Sincerely, Constance C. Holland Director Town of Little Creek Comprehensive Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS TOWN, COUNTY, AND STATE OFFICIALS.................................................................................... -

Living Blues 2021 Festival Guide

Compiled by Melanie Young Specific dates are provided where possible. However, some festivals had not set their 2021 dates at press time. Due to COVID-19, some dates are tentative. Please contact the festivals directly for the latest information. You can also view this list year-round at www.LivingBlues.com. Living Blues Festival Guide ALABAMA Foley BBQ & Blues Cook-Off March 13, 2021 Blues, Bikes & BBQ Festival Juneau Jazz & Classics Heritage Park TBA TBA Foley, Alabama Alabama International Dragway Juneau, Alaska 251.943.5590 2021Steele, Alabama 907.463.3378 www.foleybbqandblues.net www.bluesbikesbbqfestival.eventbrite.com jazzandclassics.org W.C. Handy Music Festival Johnny Shines Blues Festival Spenard Jazz Fest July 16-27, 2021 TBA TBA Florence, Alabama McAbee Activity Center Anchorage, Alaska 256.766.7642 Tuscaloosa, Alabama spenardjazzfest.org wchandymusicfestival.com 205.887.6859 23rd Annual Gulf Coast Ethnic & Heritage Jazz Black Belt Folk Roots Festival ARIZONA Festival TBA Chandler Jazz Festival July 30-August 1, 2021 Historic Greene County Courthouse Square Mobile, Alabama April 8-10, 2021 Eutaw, Alabama Chandler, Arizona 251.478.4027 205.372.0525 gcehjazzfest.org 480.782.2000 blackbeltfolkrootsfestival.weebly.com chandleraz.gov/special-events Spring Fling Cruise 2021 Alabama Blues Week October 3-10, 2021 Woodystock Blues Festival TBA May 8-9, 2021 Carnival Glory Cruise from New Orleans, Louisiana Tuscaloosa, Alabama to Montego Bay, Jamaica, Grand Cayman Islands, Davis Camp Park 205.752.6263 Bullhead City, Arizona and Cozumel, -

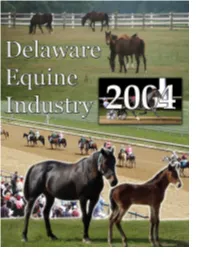

Delaware Agricultural Statistics Service, for His Hard Work in Designing, Implementing, Evaluating This Study and Preparing It for Publication

Dear Friend of Delaware Agriculture: I am very pleased and proud to present the results of the 2004 Delaware Equine Study, the first ever comprehensive study of this important segment of our agricultural industry. I want to thank Governor Ruth Ann Minner, the Delaware General Assembly, the racing commissions, and the Delaware Standardbred Breeders’ Fund for providing the funding for this project. I also want to thank the Delaware Equine Council for their help and each and every person who voluntarily participated in this very important study. As clearly shown by the numbers contained within this report, the equine industry’s importance to Delaware’s economy is significant and growing. In addition to the expenditures Delaware equine owners and operations make into the state economy, our racetracks, equine show and competition facilities, breeding, training, and boarding operations attract thousands from outside of Delaware who also expend significantly into our state economy. Not only does the industry directly provide jobs for thousands of Delawareans, but also indirectly through expenditures made for feed and bedding, veterinarian services, equipment, grooming and tack supplies, maintenance and repair and other sectors of the industry’s infrastructure. Equine and equine operations make significant contributions to the quality of life in Delaware by keeping land in open space, and providing a wide diversity of recreational activities available to the general public. As spectators or participants, countless Delawareans enjoy equine racing, shows and competitions, pony rides, trail and pleasure riding, and much more. For many, the view of Delaware from atop a horse is the best one. I know firsthand how important equines are and have been socially and recreationally to my family and to the quality of life of many others in Delaware. -

2025 Metropolitan Transportation Plan

Wilmington Area Planning Council 2025 Update CONNECTIONS to the st 21 Century 2025 Metropolitan Transportation Plan Adopted February 23, 2000 Wilmington Area Planning Council 850 Library Avenue, Suite 100 Newark, DE 19711 Phone (302) 737-6205 Email [email protected] Fax (302) 737-9584 Web www.wilmapco.org Wilmington Area Planning Council * Council: Anne P. Canby, Secretary, Delaware Department of Transportation, Chairperson Robert J. Alt, Mayor, City of Elkton, Vice Chair Nelson K. Bolender, President, Cecil County Commissioners Jeffrey W. Bullock, Chief of Staff, Delaware Governor’s Office Thomas P. Gordon, County Executive, New Castle County James F. Grant, Mayor, Town of Odessa Marsha J. Kaiser, Director, Maryland Department of Transportation Office of Planning & Capital Programming Raymond C. Miller, Director, Delaware Transit Corporation James H. Sills, Jr., Mayor, City of Wilmington Technical Advisory Committee: Public Advisory Committee: Anna Marie Gonnella, Delaware River & Bay Authority, Chairperson Anita Puglisi, City of Newark Citizen, Chairperson Phil Wheeler, Delaware Department of Natural Resources & Barbara Washam, Upper East Side Neighborhood Association, Vice Chair Environmental Control, Vice Chair Doug Andrews, Delmarva Rail Passenger Association Eugene E. Abbott, Delaware Department of Transportation David Blankenship, Wilmington Department of Public Works David Baker, Southern New Castle County Citizen Anthony J. Di Giacomo, Cecil County Office of Planning and Jan Baty, Newark Planning Commission Zoning & Parks and Recreation Lynn Broaddus, Brandywine Hundred Citizen Bobbie Geier, Delaware Transit Corporation Harry Brown, City of Wilmington Citizen Markus R. Gradecak, Maryland Office of Planning John J. Casey, Delaware Contractors Association Herbert M. Inden, Delaware Office of State Planning Bob Dietrich, Delaware Motor Transport Association Coordination Gwinneth Kaminsky Rivera, Wilmington Department of Planning Dennis Flint, White Clay Creek Bicycle Club James P. -

USGS Pfe , Science for a Changing World \ \C

USGS pfe , science for a changing world \ \c. £ j* y>8 i V° In cooperation with Dover Air Force Base Assessment of Natural Attenuation of Contamination from Three Source Areas in the East Management Unit, Dover Air Force Base, Kent County, Delaware Water-Resources Investigations Report 98-4153 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey CONVERSION FACTORS, VERTICAL DATUM, AND ABBREVIATIONS Multiply By To obtain inch per year (in/yr) 0.02540 meter per year foot (ft) 0.3048 meter foot per day (ft/d) 0.3048 meter per day foot per year (ft/yr) 0.3048 meter per year mile (mi) 1.609 kilometer Sea Level: In this report, "sea level" refers to the National Geodetic Vertical Datum of 1929 a geodetic datum derived from a general adjustment of the first-order level nets of the United States and Canada, formerly called Sea Level Datum of 1929. Abbreviated water-quality units used in this report: Chemical concentration for water is given in milligrams per liter (mg/L), or micrograms per liter (jig/L). U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Assessment of Natural Attenuation of Contamination from Three Source Areas in the East Management Unit, Dover Air Force Base, Kent County, Delaware by L Joseph Bachman, Martha L Cashel, and Barbara A. Bekins Water-Resources Investigations Report 98-4153 In cooperation with Dover Air Force Base Baltimore, Maryland 1998 U.S. Department of the Interior Bruce Babbitt, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Thomas J. Casadevall, Acting Director The use of trade, product, or firm names in this report is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. -

Underground Railroad Byway Delaware

Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Byway Delaware Chapter 3.0 Intrinsic Resource Assessment The following Intrinsic Resource Assessment chapter outlines the intrinsic resources found along the corridor. The National Scenic Byway Program defines an intrinsic resource as the cultural, historical, archeological, recreational, natural or scenic qualities or values along a roadway that are necessary for designation as a Scenic Byway. Intrinsic resources are features considered significant, exceptional and distinctive by a community and are recognized and expressed by that community in its comprehensive plan to be of local, regional, statewide or national significance and worthy of preservation and management (60 FR 26759). Nationally significant resources are those that tend to draw travelers or visitors from regions throughout the United States. National Scenic Byway CMP Point #2 An assessment of the intrinsic qualities and their context (the areas surrounding the intrinsic resources). The Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Byway offers travelers a significant amount of Historical and Cultural resources; therefore, this CMP is focused mainly on these resource categories. The additional resource categories are not ignored in this CMP; they are however, not at the same level of significance or concentration along the corridor as the Historical and Cultural resources. The resources represented in the following chapter provide direct relationships to the corridor story and are therefore presented in this chapter. A map of the entire corridor with all of the intrinsic resources displayed can be found on Figure 6. Figures 7 through 10 provide detailed maps of the four (4) corridors segments, with the intrinsic resources highlighted. This Intrinsic Resource Assessment is organized in a manner that presents the Primary (or most significant resources) first, followed by the Secondary resources. -

Bringing Kids Back to Nature by Theresa Gawlas Medoff

Child’s Play Bringing Kids Back to Nature By Theresa Gawlas Medoff 24 / O UTDOOR D ELAWARE Winter 2012 the Kaiser Family Foundation, today’s to connect with nature, and to gain school-age children spend 6.5 hours a day a sense of stewardship,” says Rachael with electronic media — and just minutes Phillos, nature center manager at Killens playing outdoors in unstructured activi- Pond State Park. ties. That’s a statistic that the folks at DN- The Educational Side REC’s Division of Parks and Recreation State park naturalists say that they are are acutely aware of, and one they are astounded sometimes by the naivety of trying their best to turn around. The some of the children who come to the Participants in Bellevue major part of the mission of Delaware parks on school fi eld trips. “They step off State Park’s Youth Fishing Tournament State Parks has always been to get people the bus and see more than four trees to- show off their catch. outside and into nature, says Ray Bivens, gether and think they are in the jungle,” DNREC operations, maintenance and Phillos says. programming section administrator. But “We often have kids who’ve never at a time when children are increasingly been in a forest before,” adds Angel nature deprived, our parks are doing Burns, naturalist at White Clay Creek more than ever to attract families by add- State Park. “They’re very concerned ing new programs, making people aware about going into the woods and want to of existing offerings, and increasing the know if there are bears out there.” accessibility of the parks. -

Fort Delaware State Park New Castle County, Delaware

Historical Analysis and Map of Vegetation Communities, Land Covers, and Habitats of Fort Delaware State Park New Castle County, Delaware Lower Delaware River Watershed Submitted to: Delaware State Parks Delaware Division of State Parks 89 Kings Highway Dover, DE 19901 Completed by: Robert Coxe, Ecologist Delaware Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program Wildlife Section, Delaware Division of Fish and Wildlife Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control 4876 Hay Point Landing Road Smyrna, DE 19977 December 3, 2012 Table of Contents Chapter 1: Introduction and Methods ............................................................................................. 4 Setting of Fort Delaware State Park ............................................................................................ 4 History and Formation of Fort Delaware State Park .................................................................. 6 Soils and Geology of Fort Delaware State Park ........................................................................ 6 Underlying Geology................................................................................................................ 6 Soils......................................................................................................................................... 6 Discussion of vegetation communities in general and why they are important in management 9 Discussion of Sea-Level Rise and why it may affect the vegetation communities at Fort Delaware State Park ...................................................................................................................