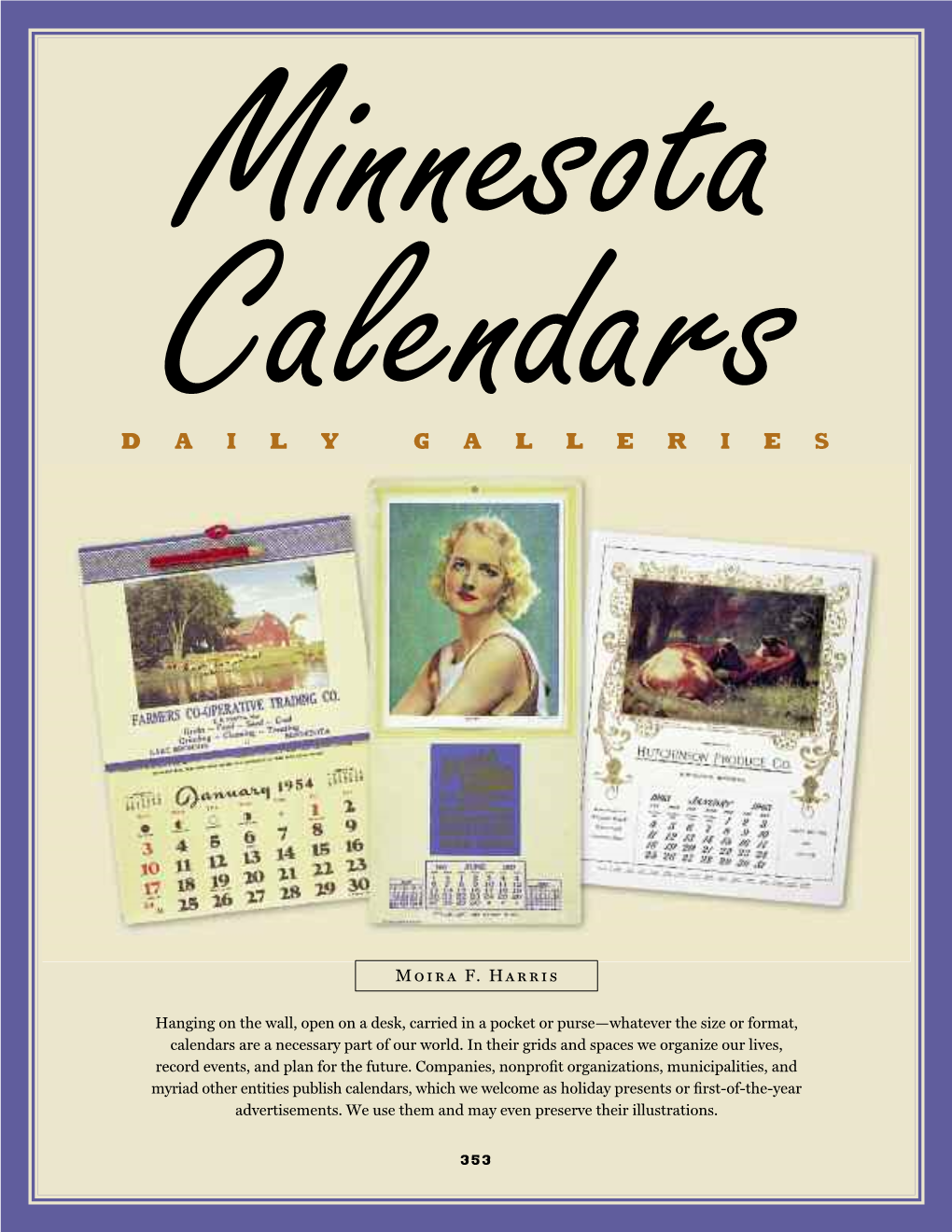

Minnesota Calendars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

®L)T Finjtn Lejus-®Lisenitr O the LINDEN NEWS, Eetablished 1927

< t 0 ®l)t finJtn lejus-®lisenitr O The LINDEN NEWS, eetablished 1927. combined with The LINDEN OBSERVER, established 1920. Entered second class ma.. nui’er PRICE: 5 Cents Vol. II, No. 45 8 PAGES LINDEN, N. J, THURSDAY, MAY 2, 1957 fie I '■ *1' L ‘‘ d e'i. N J * LINDEN Linden Library Director ^ I.iiideii Dancer ^Know Yourf Fealiircal in Oh io SCENE To Assume State Chair | Viola Maihl, director o f : Policeman Robert F. Lohr of 1309 Thel ti.e Linden Public Library, who by PETE BARTUS ma terrace, a senior at the New ha.< been .serving a.s chairman of Brunswick evening division of the library development commit Rutgers University, has been tee of the New Jersey Library A.s- Patrolman George Modrak lives 1 elected to the Hutger.s Honor .sociation, will become pre.sident- a. 319 CurtLs Street and was bom i Society ,the top honor group of elect of the state organization at in Ne-«' York City on September j the four evening branches of the annual .spring conference, to 12, 1928. He attended Public j University College, it ha.s been be held at the Hotel Berkeley- School No. l , j announced by the University. Carteret, Asbury Park, on May 2, Linden Jr. High Initiation of the twenty-six men S, and 4. School, and -v.-a.s | selected wil Ibe made on Satur Mi.s.s Harriet Proudfoot will be graduated from j day, April 27, at 7;00P.M. at come president of the Children’s Linden H ig h ; Zig’s Restaurant. -

World War I Poster and Ephemera Collection: Finding Aid

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c86h4kqh Online items available World War I Poster and Ephemera Collection: Finding Aid Finding aid prepared by Diann Benti. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Prints and Ephemera The Huntington Library 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 2014 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. World War I Poster and Ephemera priWWI 1 Collection: Finding Aid Overview of the Collection Title: World War I Poster and Ephemera Collection Dates (inclusive): approximately 1914-1919 Collection Number: priWWI Extent: approximately 700 items Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Prints and Ephemera 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: This collection contains approximately 700 World War I propaganda posters and related ephemera dating from approximately 1914 to 1919. The posters were created primarily for government and military agencies, as well as private charities such as the American Committee for Relief in the Near East. While the majority of the collection is American, it also includes British and French posters, and a few Austro-Hungarian/German, Canadian, Belgian, Dutch, Italian, Polish, and Russian items. Language: English. Note: Finding aid last updated on July 24, 2020. Access Open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. -

Rolf Armstrong Biography

ARTIST BROCHURE Decorate Your Life™ ArtRev.com Rolf Armstrong Rolf Armstrong is best known for the calendar girl illustrations he produced for Brown and Bigelow's Dream Girl in 1919. Sometimes labeled the father of the American pin-up, his pastel illustrations set the glamour-art standard for feminine beauty that would dominate the genre for the next four decades. He was also noted for his portraits of silent film and motion picture stars as well as for his pin-ups and magazine covers. Armstrong was born in 1889 in Bay City, Michigan and settled in Bayside, New York on the shore of Little Neck Bay, while keeping his studio in Manhattan. His interest in art developed shortly after his family moved to Detroit in 1899. His earlier works are primarily 'macho' type sketches of boxers, sailors, and cowboys. Armstrong had previously been a professional boxer and accomplished seaman, and the ruggedly handsome artist was seldom seen without his yachting cap. He continued to sail his entire life and could be found sailing with movie stars such as James Cagney when the Armstrongs were in California. In fact, he was a winner of the Mab Trophy with his sailing canoe "Mannikin" and competed in other events at the Canoe championship of America held in the 1000 Islands in New York. Armstrong left Detroit for Chicago to attend the Art Institute of Chicago. While he was there he taught baseball, boxing, and art. New York became Armstrong's next home and magazine covers became his primary focus. His first was in 1912 for Judge magazine. -

Papers/Records /Collection

A Guide to the Papers/Records /Collection Collection Summary Collection Title: World War I Poster and Graphic Collection Call Number: HW 81-20 Creator: Cuyler Reynolds (1866-1934) Inclusive Dates: 1914-1918 Bulk Dates: Abstract: Quantity: 774 Administrative Information Custodial History: Preferred Citation: Gift of Cuyler Reynolds, Albany Institute of History & Art, HW 81-20. Acquisition Information: Accession #: Accession Date: Processing Information: Processed by Vicary Thomas and Linda Simkin, January 2016 Restrictions Restrictions on Access: 1 Restrictions on Use: Permission to publish material must be obtained in writing prior to publication from the Chief Librarian & Archivist, Albany Institute of History & Art, 125 Washington Avenue, Albany, NY 12210. Index Term Artists and illustrators Anderson, Karl Forkum, R.L. & E. D. Anderson, Victor C. Funk, Wilhelm Armstrong, Rolf Gaul, Gilbert Aylward, W. J. Giles, Howard Baldridge, C. LeRoy Gotsdanker, Cozzy Baldridge, C. LeRoy Grant, Gordon Baldwin, Pvt. E.E. Greenleaf, Ray Beckman, Rienecke Gribble, Bernard Benda, W.T. Halsted, Frances Adams Beneker, Gerritt A. Harris, Laurence Blushfield, E.H. Harrison, Lloyd Bracker, M. Leone Hazleton, I.B. Brett, Harold Hedrick, L.H. Brown, Clinton Henry, E.L. Brunner, F.S. Herter, Albert Buck, G.V. Hoskin, Gayle Porter Bull, Charles Livingston Hukari, Pvt. George Buyck, Ed Hull, Arthur Cady, Harrison Irving, Rea Chapin, Hubert Jack. Richard Chapman, Charles Jaynes, W. Christy, Howard Chandler Keller, Arthur I. Coffin, Haskell Kidder Copplestone, Bennett King, W.B. Cushing, Capt. Otho Kline, Hibberd V.B Daughterty, James Leftwich-Dodge, William DeLand, Clyde O. Lewis, M. Dick, Albert Lipscombe, Guy Dickey, Robert L. Low, Will H. Dodoe, William de L. -

Women Pin-Up Artists of the First Half of the Twentieth Century While M

Running Head: ALL AMERICAN GIRLS 1 All American Girls: Women Pin-Up Artists of the First Half of the Twentieth Century While male illustrators including Alberto Vargas (1896–1982), George Petty (1894–1975), and Gil Elvgren (1914–80) are synonymous with the field of early-twentieth-century pin-up art, there were, in fact, several women who also succeeded in the genre. Pearl Frush (1907–86), Zoë Mozert (1907–93), and Joyce Ballantyne (1918–2006) are three such women; each of whom established herself as a successful pin-up artist during the early to mid-twentieth century. While the critical study of twentieth-century pin-art is still a burgeoning field, most of the work undertaken thus far has focused on the origin of the genre and the work of its predominant artists who have, inevitably, been men. Women pin-up artists have been largely overlooked, which is neither surprising nor necessarily intentional. While illustration had become an acceptable means of employment for women by the late-nineteenth century, the pin-up genre of illustration was male dominated. In a manifestly sexual genre, it is not surprising that women artists would be outnumbered by their male contemporaries, as powerful middle-class gender ideologies permeated American culture well into the mid-twentieth century. These ideologies prescribed notions of how to live and present oneself—defining what it meant to be, or not be, respectable.1 One of the most powerful systems of thought was the domestic ideology, which held that a woman’s moral and spiritual presence was key to not only a successful home but also to the strength of a nation (Kessler-Harris 49). -

Nación E Identidad En Los Imaginarios Visuales De La Argentina

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk ARBOR Ciencia, Pensamiento broughty Cultura to you by CORE CLXXXV 740 noviembre-diciembre (2009) 1283-1298provided ISSN:by Directory 0210-1963 of Open Access Journals doi: 10.3989/arbor.2009.740n1091 NACIÓN E IDENTIDAD EN LOS NATION AND IDENTITY TO IMAGINARIOS VISUALES DE LA THE VISUAL IMAGINARIES IN ARGENTINA. SIGLOS XIX Y XX ARGENTINA AT 19th AND 20th CENTURIES Mariana Giordano IIGHI-CONICET/UNNE ABSTRACT: The construction of symbolic regards and itineraries re- RESUMEN: La necesidad de construir referentes e itinerarios sim- ferring on the “Nation” in Argentina begins in the years following bólicos sobre la “Nación” en la Argentina comienza en los años the emancipation of the Rio de la Plata in 1810. The eyes of foreign que siguieron a la emancipación del Río de la Plata en 1810. La and argentines artists will focus on the nineteenth century on repre- mirada de artistas extranjeros y argentinos se centrará en gran sentations of the Pampa, the indigenous and gaucho as symbols of parte del siglo XIX en representaciones de la Pampa, el indígena y identity, forming an imaginary that is updated in different contexts el gaucho como símbolos identitarios, constituyendo un imaginario and using differents art languages in 19th and 20th century. Cos- que se reactualizará en distintos contextos y acudiendo a diferen- mopolitism and nationalism are two lines through which transmitted tes lenguajes a lo largo de los siglos XIX y XX. Cosmopolitismo y the positions, debates and visions on the Argentine identity, forging nacionalismo se constituyen en dos ejes por donde transitarán las an hegemonic imaginary focused on what was produced and ens- posturas, debates y visiones sobre la identidad argentina, forjando hrined in Buenos Aires, with little or no participation from regional un imaginario hegemónico centrado en lo producido y consagrado productions. -

Molina Campos En La UCA Derecho: 50 Años

1 de junio de 2007 | año VI | número 97 | Publicación quincenal de la Pontificia Universidad Católica Argentina Derecho: 50 años Se realizó en el Auditorio Mons. Derisi el segundo acto institucional “Cami- no al Cincuentenario”, or- ganizado por la Facultad de Derecho de la UCA con el aporte de la Dirección de Relaciones Institucio- nales de la Universidad. Durante el evento, que co- menzó con una Misa de acción de gracias por los fructíferos años de trabajo cumplidos, se rindió un emotivo homenaje a los ex Decanos que pasaron por la Facultadyalapri- mera generación de gra- duados. (Páginas2y3) Molina Campos en la UCA (Páginas 13 a 15) UCActualidad DERECHO Derecho: Cincuenta años de identidad católica Se realizó en el Auditorio Mons. Derisi el segundo acto institucional “Camino al Cincuentenario”, organizado por la Facultad de Derecho de la UCA con el apoyo de la Dirección de Relaciones Institucionales de la Universidad. El evento comenzó con una Misa de acción de gracias por los años de fructífero trabajo y continuó con un emotivo homenaje a los ex Decanos que pasaron por la Facultad y a la primera generación de graduados. Dres. Osvaldo Mirás, Gabriel Limodio y Julio Ojea Quintana, durante la celebración del acto institucional. Rumbo a la celebración de los cin- cincuenta años. En aquella ocasión, el graduados de la primera promoción; fa- cuenta años de la Universidad Católica R e c t o r, Mons. Dr. Alfredo Zecca, seña- miliares de los ex Decanos fallecidos y A rgentina, se realizó en el A u d i t o r i o ló que 2007 debe ser un año jubilar pa- de los graduados presentes, alumnos; Mons. -

Contenidos 06

1. 2. 3. Contenidos 06. 25. 48. ENTREVISTAS NUESTRAS ENTRE COPAS Dr. Hugo Petrone, CIUDADES Sabores regionales: la presidente de CUCAIBA: Carmen de Patagones: la nueva tendencia de la no todo se termina con la ciudad más austral de coctelería argentina muerte, hay algo más la provincia 12. 30. 52. 62. DE VIAJE SECRETOS, SABORES ACTUALIDAD SALIDAS, San Rafael, Mendoza: naturaleza Y TENDENCIAS TERAPÉUTICA CULTURA Y OCIO para disfrutar y buenos Gastronomía mexicana: Vitamina D: la vitamina • Cuatro museos vinos para brindar por ella color, sabor y picante con que viene del sol y sus efectos poco tradicionales mucha historia y más futuro • En pocas palabras • Samanta Schweblin 19. 36. 56. 64. NUESTROS MÉDICOS ENTREVISTAS ECO MUNDO PERFILES Ecología y oportunidades: Molina Campos, Disney Dr. Pedro Dragone: Pablo Massey: “cuando un médico nunca puede decir diez inventos para cuidar y por qué Goofy nunca hasta acá llegué, siempre veo un plato que está el planeta fue un buen gaucho quiere hacer más cosas por salir a la mesa, ya sé si ese plato está rico o no” 44. 60. TECNOLOGÍA MUNDO FEMEBA Redes sociales: entre Área de calidad y seguridad la hipercomunicación del paciente FEMEBA: hacien- y el aislamiento do una medicina más segura para todos Director: Colaboradores: Coordinación: Impresión: La revista SOMOS MÉDICOS es propiedad de la Federación Médica de la Provincia de Buenos Aires. Guillermo Cobián Julia Langoni Dolores Massey Arte y Letras S.A. Editorial Fundación FEMEBA. Gabriel Negri Av. Mitre 3027, Munro. Calle 5 n° 473 (41 y 42). La Plata. (1900). Staff Comité Editorial: Tomás Malato Redacción y Edición: Buenos Aires, noviembre de 2019. -

A Cultural Trade? Canadian Magazine Illustrators at Home And

A Cultural Trade? Canadian Magazine Illustrators at Home and in the United States, 1880-1960 A Dissertation Presented by Shannon Jaleen Grove to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor oF Philosophy in Art History and Criticism Stony Brook University May 2014 Copyright by Shannon Jaleen Grove 2014 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Shannon Jaleen Grove We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. Michele H. Bogart – Dissertation Advisor Professor, Department of Art Barbara E. Frank - Chairperson of Defense Associate Professor, Department of Art Raiford Guins - Reader Associate Professor, Department of Cultural Analysis and Theory Brian Rusted - Reader Associate Professor, Department of Art / Department of Communication and Culture University of Calgary This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School Charles Taber Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Dissertation A Cultural Trade? Canadian Magazine Illustrators at Home and in the United States, 1880-1960 by Shannon Jaleen Grove Doctor of Philosophy in Art History and Criticism Stony Brook University 2014 This dissertation analyzes nationalisms in the work of Canadian magazine illustrators in Toronto and New York, 1880 to 1960. Using a continentalist approach—rather than the nationalist lens often employed by historians of Canadian art—I show the existence of an integrated, joint North American visual culture. Drawing from primary sources and biography, I document the social, political, corporate, and communication networks that illustrators traded in. I focus on two common visual tropes of the day—that of the pretty girl and that of wilderness imagery. -

Certificates of Authorization

Certificates of Authorization Included below are all WV ACTIVE COAs licensed through June 30, 2015. As of the date of this posting, all Company COA updates received prior to February 11, 2015 are included. The next Roster posting will be in May 2015, immediately prior to renewal season, updating those in good standing through June 30, 2015. COA WV COA # Company Name Address 1 Address 2 City State Zip Engineer‐In‐Charge WV PE # EXPIRATION C04616‐00 2301 STUDIO, PLLC D.B.A. BLOC DESIGN, PLLC 1310 SOUTH TRYON STREET SUITE 111 CHARLOTTE NC 28203 WILLIAM LOCKHART 017282 6/30/2015 C04740‐00 3B CONSULTING SERVICES, LLC 140 HILLTOP AVENUE LEBANON VA 24266 PRESTON BREEDING 018263 6/30/2015 C04430‐00 3RD GENERATION ENGINEERING, INC. 7920 BELT LINE ROAD SUITE 591 DALLAS TX 75254 MARK FISHER 019434 6/30/2015 C02651‐00 4SE, INC. 7 RADCLIFFE STREET SUITE 301 CHARLESTON SC 29403 GEORGE BURBAGE 015290 6/30/2015 C04188‐00 4TH DIMENSION DESIGN, INC. 817 VENTURE COURT WAUKESHA WI 53189 JOHN GROH 019415 6/30/2015 C02308‐00 A & A CONSULTANTS, INC. 707 EAST STREET PITTSBURGH PA 15212 JACK ROSEMAN 007481 6/30/2015 C02125‐00 A & A ENGINEERING, CIVIL & STRUCTURAL ENGINEERS 5911 RENAISSANCE PLACE SUITE B TOLEDO OH 43623 OMAR YASEIN 013981 6/30/2015 C01299‐00 A 1 ENGINEERING, INC. 5314 OLD SAINT MARYS PIKE PARKERSBURG WV 26104 ROBERT REED 006810 6/30/2015 C03979‐00 A SQUARED PLUS ENGINEERING SUPPORT GROUP, LLC 3477 SHILOH ROAD HAMPSTEAD MD 21074 SHERRY ABBOTT‐ADKINS 018982 6/30/2015 C02552‐00 A&M ENGINEERING, LLC 3402 ASHWOOD LANE SACHSE TX 75048 AMMAR QASHSHU 016761 6/30/2015 C01701‐00 A. -

Annual Report 2Oo8–2Oo9

annual report 2oo8–2oo9 4o years illustration art 1 president’s letter After the fabulous recognition and its citizens. Following inspiring speeches achievements of 2008, including the from other elected officials, Laurie receipt of the National Humanities Norton Moffatt honored the vision and Medal at the White House, I really tenacity of our Founding Trustees (all anticipated a “breather” of sorts in women), who represent both our proud 2009. Fortunately, as has become heritage and great potential. From Corner the tradition of Norman Rockwell House to New England Meeting House, Museum, new highs become the Norman Rockwell Museum has assumed launching pad for new possibilities, its rightful position among our nation’s and 2009 was no exception! most visited cultural monuments. 2009 was indeed a watershed year The gathering of three generations for the Museum as we celebrated of the Rockwell family was a source our 40th anniversary. This milestone of great excitement for the Governor, captured in all its glory the hard work, our Founding Trustees, and all of us. We vision, and involvement of multiple were privileged to enjoy the sculptures generations of staff, benefactors, of Peter Rockwell, Rockwell’s youngest friends, and neighbors. son, which were prominently displayed across our bucolic campus and within Celebrating our 40th anniversary was our galleries. It was an evening to be not confined to our birthday gala on July remembered. 9th, but that gathering certainly was its epicenter. With hundreds of Museum american MUSEUMS UNDER -

Until We Win La Guerra. Transformaciones En La Obra De Molina Campos a Contraluz Del Panamericanismo

DOI 10.22370/panambi.2019.8.1321 [ PAGS. 75 - 87 ] Panambí n.8 Valparaíso JUN. 2019 ISSN 0719-630X Until we win la guerra. Transformaciones en la obra de Molina Campos a contraluz del panamericanismo. Dra. Fabiana Serviddio Universidad Nacional de Tres de Febrero [email protected] Artículo bajo licencia Creative Commons Atribución 4.0 Internacional (CC BY 4.0) ENVIADO: 2019-05-03 ACEPTADO: 2019-06-11 RESUMEN RESUMO ABSTRACT Este artículo propone partir de un Este artigo propõe, a partir da This article seeks to present a planteo problemático de la obra visual problemática do trabalho visual do problematic description of Argentine del artista argentino Florencio Molina artista argentino Florencio Molina artist Florencio Molina Campos’ visual Campos, y detenerse en el análisis de Campos para analisar a sua colaboração artworks to analyze his contribution as su colaboración como asesor artístico como assessor artístico da Walt Disney an artistic adviser for the Walt Disney para la Walt Disney Pictures, en un Pictures, em um projeto cinematográfico Pictures, in a film project developed as proyecto fílmico surgido a partir de surgido da Política de Boa Vizinhança part of the Good Neighbor policy during la Política del Buen Vecino durante la durante a Segunda Guerra Mundial. the Second World War. The sensitive Segunda Guerra. La modificación del A modificação do caráter de suas changes his artworks gained in the carácter de sus imágenes en los años imagens nos anos seguintes procurou following years meant to circumscribe subsiguientes buscó circunscribir las circunscrever as repercussões their symbolic repercussions in a repercusiones simbólicas de las mismas simbólicas das imagens em um conflictive scenario in which Inter- en un escenario conflictivo en el que cenário conflitivo no qual as trocas American interchanges had to back the los intercambios interamericanos interamericanas tiveram que sustentar continental political alliances.