Women Pin-Up Artists of the First Half of the Twentieth Century While M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

®L)T Finjtn Lejus-®Lisenitr O the LINDEN NEWS, Eetablished 1927

< t 0 ®l)t finJtn lejus-®lisenitr O The LINDEN NEWS, eetablished 1927. combined with The LINDEN OBSERVER, established 1920. Entered second class ma.. nui’er PRICE: 5 Cents Vol. II, No. 45 8 PAGES LINDEN, N. J, THURSDAY, MAY 2, 1957 fie I '■ *1' L ‘‘ d e'i. N J * LINDEN Linden Library Director ^ I.iiideii Dancer ^Know Yourf Fealiircal in Oh io SCENE To Assume State Chair | Viola Maihl, director o f : Policeman Robert F. Lohr of 1309 Thel ti.e Linden Public Library, who by PETE BARTUS ma terrace, a senior at the New ha.< been .serving a.s chairman of Brunswick evening division of the library development commit Rutgers University, has been tee of the New Jersey Library A.s- Patrolman George Modrak lives 1 elected to the Hutger.s Honor .sociation, will become pre.sident- a. 319 CurtLs Street and was bom i Society ,the top honor group of elect of the state organization at in Ne-«' York City on September j the four evening branches of the annual .spring conference, to 12, 1928. He attended Public j University College, it ha.s been be held at the Hotel Berkeley- School No. l , j announced by the University. Carteret, Asbury Park, on May 2, Linden Jr. High Initiation of the twenty-six men S, and 4. School, and -v.-a.s | selected wil Ibe made on Satur Mi.s.s Harriet Proudfoot will be graduated from j day, April 27, at 7;00P.M. at come president of the Children’s Linden H ig h ; Zig’s Restaurant. -

World War I Poster and Ephemera Collection: Finding Aid

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c86h4kqh Online items available World War I Poster and Ephemera Collection: Finding Aid Finding aid prepared by Diann Benti. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Prints and Ephemera The Huntington Library 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 2014 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. World War I Poster and Ephemera priWWI 1 Collection: Finding Aid Overview of the Collection Title: World War I Poster and Ephemera Collection Dates (inclusive): approximately 1914-1919 Collection Number: priWWI Extent: approximately 700 items Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Prints and Ephemera 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: This collection contains approximately 700 World War I propaganda posters and related ephemera dating from approximately 1914 to 1919. The posters were created primarily for government and military agencies, as well as private charities such as the American Committee for Relief in the Near East. While the majority of the collection is American, it also includes British and French posters, and a few Austro-Hungarian/German, Canadian, Belgian, Dutch, Italian, Polish, and Russian items. Language: English. Note: Finding aid last updated on July 24, 2020. Access Open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. -

Rolf Armstrong Biography

ARTIST BROCHURE Decorate Your Life™ ArtRev.com Rolf Armstrong Rolf Armstrong is best known for the calendar girl illustrations he produced for Brown and Bigelow's Dream Girl in 1919. Sometimes labeled the father of the American pin-up, his pastel illustrations set the glamour-art standard for feminine beauty that would dominate the genre for the next four decades. He was also noted for his portraits of silent film and motion picture stars as well as for his pin-ups and magazine covers. Armstrong was born in 1889 in Bay City, Michigan and settled in Bayside, New York on the shore of Little Neck Bay, while keeping his studio in Manhattan. His interest in art developed shortly after his family moved to Detroit in 1899. His earlier works are primarily 'macho' type sketches of boxers, sailors, and cowboys. Armstrong had previously been a professional boxer and accomplished seaman, and the ruggedly handsome artist was seldom seen without his yachting cap. He continued to sail his entire life and could be found sailing with movie stars such as James Cagney when the Armstrongs were in California. In fact, he was a winner of the Mab Trophy with his sailing canoe "Mannikin" and competed in other events at the Canoe championship of America held in the 1000 Islands in New York. Armstrong left Detroit for Chicago to attend the Art Institute of Chicago. While he was there he taught baseball, boxing, and art. New York became Armstrong's next home and magazine covers became his primary focus. His first was in 1912 for Judge magazine. -

VINTAGE POSTERS FEBRUARY 25 Our Annual Winter Auction of Vintage Posters Features an Exceptional Selection of Rare and Important Art Nouveau Posters

SCALING NEW HEIGHTS There is much to report from the Swann offices these days as new benchmarks are set and we continue to pioneer new markets. Our fall 2013 season saw some remarkable sales results, including our top-grossing Autographs auction to date—led by a handwritten Mozart score and a collection of Einstein letters discussing his general theory of relativity, which brought $161,000 each. Check page 7 for more post-sale highlights from the past season. On page 7 you’ll also find a brief tribute to our beloved Maps specialist Gary Garland, who is retiring after nearly 30 years with Swann, and the scoop on his replacement, Alex Clausen. Several special events are in the works for our winter and spring sales, including a talk on the roots of African-American Fine Art that coincides with our February auction, a partnership with the Library Company of Philadelphia and a discussion of the growing collecting field of vernacular photography. Make sure we have your e-mail address so you’ll receive our invites. THE TRUMPET • WINTER / SPRING 2014 • VOLUME 28, NUMBER 2 20TH CENTURY ILLUSTRATION JANUARY 23 Following the success of Swann’s first dedicated sale in this category, our 2014 auction features more excellent examples by famous names. There are magazine and newspaper covers and cartoons by R.O. Blechman, Jules Feiffer, David Levine, Ronald Searle, Edward Sorel, Richard Taylor and James Thurber, as well as works by turn-of-the-20th-century magazine and book illustrators such as Howard Chandler Christy and E.W. Kemble. Beloved children’s book artists include Ludwig Bemelmans, W.W. -

Papers/Records /Collection

A Guide to the Papers/Records /Collection Collection Summary Collection Title: World War I Poster and Graphic Collection Call Number: HW 81-20 Creator: Cuyler Reynolds (1866-1934) Inclusive Dates: 1914-1918 Bulk Dates: Abstract: Quantity: 774 Administrative Information Custodial History: Preferred Citation: Gift of Cuyler Reynolds, Albany Institute of History & Art, HW 81-20. Acquisition Information: Accession #: Accession Date: Processing Information: Processed by Vicary Thomas and Linda Simkin, January 2016 Restrictions Restrictions on Access: 1 Restrictions on Use: Permission to publish material must be obtained in writing prior to publication from the Chief Librarian & Archivist, Albany Institute of History & Art, 125 Washington Avenue, Albany, NY 12210. Index Term Artists and illustrators Anderson, Karl Forkum, R.L. & E. D. Anderson, Victor C. Funk, Wilhelm Armstrong, Rolf Gaul, Gilbert Aylward, W. J. Giles, Howard Baldridge, C. LeRoy Gotsdanker, Cozzy Baldridge, C. LeRoy Grant, Gordon Baldwin, Pvt. E.E. Greenleaf, Ray Beckman, Rienecke Gribble, Bernard Benda, W.T. Halsted, Frances Adams Beneker, Gerritt A. Harris, Laurence Blushfield, E.H. Harrison, Lloyd Bracker, M. Leone Hazleton, I.B. Brett, Harold Hedrick, L.H. Brown, Clinton Henry, E.L. Brunner, F.S. Herter, Albert Buck, G.V. Hoskin, Gayle Porter Bull, Charles Livingston Hukari, Pvt. George Buyck, Ed Hull, Arthur Cady, Harrison Irving, Rea Chapin, Hubert Jack. Richard Chapman, Charles Jaynes, W. Christy, Howard Chandler Keller, Arthur I. Coffin, Haskell Kidder Copplestone, Bennett King, W.B. Cushing, Capt. Otho Kline, Hibberd V.B Daughterty, James Leftwich-Dodge, William DeLand, Clyde O. Lewis, M. Dick, Albert Lipscombe, Guy Dickey, Robert L. Low, Will H. Dodoe, William de L. -

A Cultural Trade? Canadian Magazine Illustrators at Home And

A Cultural Trade? Canadian Magazine Illustrators at Home and in the United States, 1880-1960 A Dissertation Presented by Shannon Jaleen Grove to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor oF Philosophy in Art History and Criticism Stony Brook University May 2014 Copyright by Shannon Jaleen Grove 2014 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Shannon Jaleen Grove We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. Michele H. Bogart – Dissertation Advisor Professor, Department of Art Barbara E. Frank - Chairperson of Defense Associate Professor, Department of Art Raiford Guins - Reader Associate Professor, Department of Cultural Analysis and Theory Brian Rusted - Reader Associate Professor, Department of Art / Department of Communication and Culture University of Calgary This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School Charles Taber Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Dissertation A Cultural Trade? Canadian Magazine Illustrators at Home and in the United States, 1880-1960 by Shannon Jaleen Grove Doctor of Philosophy in Art History and Criticism Stony Brook University 2014 This dissertation analyzes nationalisms in the work of Canadian magazine illustrators in Toronto and New York, 1880 to 1960. Using a continentalist approach—rather than the nationalist lens often employed by historians of Canadian art—I show the existence of an integrated, joint North American visual culture. Drawing from primary sources and biography, I document the social, political, corporate, and communication networks that illustrators traded in. I focus on two common visual tropes of the day—that of the pretty girl and that of wilderness imagery. -

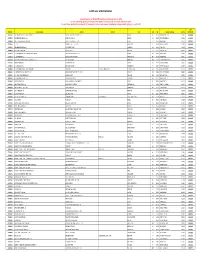

Certificates of Authorization

Certificates of Authorization Included below are all WV ACTIVE COAs licensed through June 30, 2015. As of the date of this posting, all Company COA updates received prior to February 11, 2015 are included. The next Roster posting will be in May 2015, immediately prior to renewal season, updating those in good standing through June 30, 2015. COA WV COA # Company Name Address 1 Address 2 City State Zip Engineer‐In‐Charge WV PE # EXPIRATION C04616‐00 2301 STUDIO, PLLC D.B.A. BLOC DESIGN, PLLC 1310 SOUTH TRYON STREET SUITE 111 CHARLOTTE NC 28203 WILLIAM LOCKHART 017282 6/30/2015 C04740‐00 3B CONSULTING SERVICES, LLC 140 HILLTOP AVENUE LEBANON VA 24266 PRESTON BREEDING 018263 6/30/2015 C04430‐00 3RD GENERATION ENGINEERING, INC. 7920 BELT LINE ROAD SUITE 591 DALLAS TX 75254 MARK FISHER 019434 6/30/2015 C02651‐00 4SE, INC. 7 RADCLIFFE STREET SUITE 301 CHARLESTON SC 29403 GEORGE BURBAGE 015290 6/30/2015 C04188‐00 4TH DIMENSION DESIGN, INC. 817 VENTURE COURT WAUKESHA WI 53189 JOHN GROH 019415 6/30/2015 C02308‐00 A & A CONSULTANTS, INC. 707 EAST STREET PITTSBURGH PA 15212 JACK ROSEMAN 007481 6/30/2015 C02125‐00 A & A ENGINEERING, CIVIL & STRUCTURAL ENGINEERS 5911 RENAISSANCE PLACE SUITE B TOLEDO OH 43623 OMAR YASEIN 013981 6/30/2015 C01299‐00 A 1 ENGINEERING, INC. 5314 OLD SAINT MARYS PIKE PARKERSBURG WV 26104 ROBERT REED 006810 6/30/2015 C03979‐00 A SQUARED PLUS ENGINEERING SUPPORT GROUP, LLC 3477 SHILOH ROAD HAMPSTEAD MD 21074 SHERRY ABBOTT‐ADKINS 018982 6/30/2015 C02552‐00 A&M ENGINEERING, LLC 3402 ASHWOOD LANE SACHSE TX 75048 AMMAR QASHSHU 016761 6/30/2015 C01701‐00 A. -

Annual Report 2Oo8–2Oo9

annual report 2oo8–2oo9 4o years illustration art 1 president’s letter After the fabulous recognition and its citizens. Following inspiring speeches achievements of 2008, including the from other elected officials, Laurie receipt of the National Humanities Norton Moffatt honored the vision and Medal at the White House, I really tenacity of our Founding Trustees (all anticipated a “breather” of sorts in women), who represent both our proud 2009. Fortunately, as has become heritage and great potential. From Corner the tradition of Norman Rockwell House to New England Meeting House, Museum, new highs become the Norman Rockwell Museum has assumed launching pad for new possibilities, its rightful position among our nation’s and 2009 was no exception! most visited cultural monuments. 2009 was indeed a watershed year The gathering of three generations for the Museum as we celebrated of the Rockwell family was a source our 40th anniversary. This milestone of great excitement for the Governor, captured in all its glory the hard work, our Founding Trustees, and all of us. We vision, and involvement of multiple were privileged to enjoy the sculptures generations of staff, benefactors, of Peter Rockwell, Rockwell’s youngest friends, and neighbors. son, which were prominently displayed across our bucolic campus and within Celebrating our 40th anniversary was our galleries. It was an evening to be not confined to our birthday gala on July remembered. 9th, but that gathering certainly was its epicenter. With hundreds of Museum american MUSEUMS UNDER -

The Marcus Tradition Corporate Art Curator Julie Kronick Continues the Legacy of Retail Icon Stanley Marcus Lobby Living Room

FRANK FRAZETTA DAT–SO–LA–LEE JULIAN ONDERDONK SPRING 2010 $9.95 MAGAZINE FOR THE INTELLIGENT COLLECTOR THE MARCUS TRADITION Corporate art curator Julie Kronick continues the legacy of retail icon Stanley Marcus Lobby Living Room Luxe Accommodations The French Room 1321 Commerce Street ▪ Dallas, Texas 75202 Phone: 214.742.8200 ▪ Fax: 214.651.3588 ▪ Reservations: 800.221.9083 HotelAdolphus.com CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS THE MARCUS TRADITION 60 years after Stanley Marcus launched 50 the Neiman Marcus Collection, Julie Kronick remains focused on the company’s artistic goals CREATIVE FORCE: DAT-SO-LA-LEE By the time of her death in 1925, 56 weaver was already a legend among American Indian artisans PIN-UP MASTERS With a wink and a smile, these seven 60 legendary artists are driving demand in the red-hot glamour art market IN EVERY ISSUE 4 Staff & Contributors 6 Auction Calendar 8 Looking Back … 10 Top Searches 12 Auction News 80 Experts 81 Consignment Deadlines On the cover: Neiman Marcus corporate curator Julie Kronick by Kevin Gaddis Jr. Stanley Marcus photograph courtesy Neiman Marcus. George Petty (1894-1975) Original art for True magazine (detail), 1947 Watercolor on board, 22.5 x 15 in. Sold: $38,837 October 2009 Pin-up Masters (page 60) HERITAGE MAGAZINE — SPRING 2010 3 CONTENTS TREAsures 14 WORLD COINS: 1936 Canadian Dot Cent minted after King Edward VIII abdicated to marry American divorcée 16 AMERICANA: Newly discovered campaign banner found under home floorboards 18 HOLLYWOOD MEMORABILIA: Black Cat poster and Karloff costume are testaments to horror movie’s enduring popularity Edouard-Léon Cortès (1882-1969) Porte St. -

Illustrated Books

Rare Book Miscellany: An Un-illustrated Catalog of Illustrated Books On-Line Only: Catalog # 222 Second Life Books Inc. ABAA- ILAB P.O. Box 242, 55 Quarry Road Lanesborough, MA 01237 413-447-8010 fax: 413-499-1540 Email: [email protected] Rare Book Miscellany: An Un-illustrated Catalog of Illustrated Books On-Line Only Catalog # 222 Terms : All books are fully guaranteed and returnable within 7 days of receipt. Massachusetts residents please add 5% sales tax. Postage is additional. Libraries will be billed to their requirements. Deferred billing available upon request. We accept MasterCard, Visa and American Express. ALL ITEMS ARE IN VERY GOOD OR BETTER CONDITION , EXCEPT AS NOTED . Orders may be made by mail, email, phone or fax to: Second Life Books, Inc. P. O. Box 242, 55 Quarry Road Lanesborough, MA. 01237 Phone (413) 447-8010 Fax (413) 499-1540 Email:[email protected] Search all our books at our web site: www.secondlifebooks.com Item # 70 1. AIKEN, Conrad. THEE ; A poem. Drawings by Leonard Baskin. NY: Braziller, (1967). First printing. Tall 8vo, pages not numbered. Bound in paper boards, printed in black. This is one the 200 copies printed on Arches paper by the Meridan Gravure Company, but it is not numbered. Possibly an artist's copy. Signed by the illustrator at the colophon. and author on the half-title. VG tight copy in printed publisher's box. BONNELL A59a. [52071] $150.00 2. AINSWORTH, W. Harrison. WINDSOR CASTLE ; an historical romance by ... Illustrated by George Cruikshank and Tony Johannot with designs on wood by W. -

Pin-Ups: the American Way of Art

Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo Artigo História III Pin-Ups: The American Way of Art Jéssica Cavalcante Schussel Tássia Lorenzini Varani Alunas do curso de Relações Internacionais da PUC/SP. Trabalho de avaliação final apresentado na disciplina VA3, História da América no segundo semestre de 2010. São Paulo 2010 Introdução A América sempre provocou grande atração nas pessoas ao redor do mundo1. A vontade de conhecer, morar e viver como um americano permeia os pensamentos de vários indivíduos. Mas o que os Estados Unidos da América têm de tão especial? Desde que se lançaram no cenário internacional os Estados Unidos conseguiram reunir vários aspectos (econômico, político e social) para que se consolidassem como expoente e potência mundial. E tais aspectos causam atração no mundo inteiro. Se formos analisar a história americana, seus valores, costumes e hábitos, veremos que não há nada de rebuscado e fino como o antigo centro do mundo, a Europa. O motivo disso vem desde a colonização do território, já que sua primeira população eram os puritanos expulsos da Inglaterra que repudiavam tudo que fosse europeu. Se perguntassem o que mais chama a atenção de alguém nos EUA, certamente as respostas seriam múltiplas e variadas. Esse elemento mágico, por mais contraditório que pareça se deve, principalmente, à simplicidade com que os americanos criam, vivem, trabalham e produzem. Contraditório porque à primeira vista destoa da idéia de alta cultura elaborada, grande literatura e magníficas obras de arte. Nesse espírito de simplicidade é que nasce a “arte americana”. Entre aspas, pois o que os Estados Unidos criaram como arte é tão simples e singelo que não parece ser uma arte como estamos costumados a ver. -

READ ME FIRST Here Are Some Tips on How to Best Navigate, find and Read the Articles You Want in This Issue

READ ME FIRST Here are some tips on how to best navigate, find and read the articles you want in this issue. Down the side of your screen you will see thumbnails of all the pages in this issue. Click on any of the pages and you’ll see a full-size enlargement of the double page spread. Contents Page The Table of Contents has the links to the opening pages of all the articles in this issue. Click on any of the articles listed on the Contents Page and it will take you directly to the opening spread of that article. Click on the ‘down’ arrow on the bottom right of your screen to see all the following spreads. You can return to the Contents Page by clicking on the link at the bottom of the left hand page of each spread. Direct links to the websites you want All the websites mentioned in the magazine are linked. Roll over and click any website address and it will take you directly to the gallery’s website. Keep and fi le the issues on your desktop All the issue downloads are labeled with the issue number and current date. Once you have downloaded the issue you’ll be able to keep it and refer back to all the articles. Print out any article or Advertisement Print out any part of the magazine but only in low resolution. Subscriber Security We value your business and understand you have paid money to receive the virtual magazine as part of your subscription. Consequently only you can access the content of any issue.