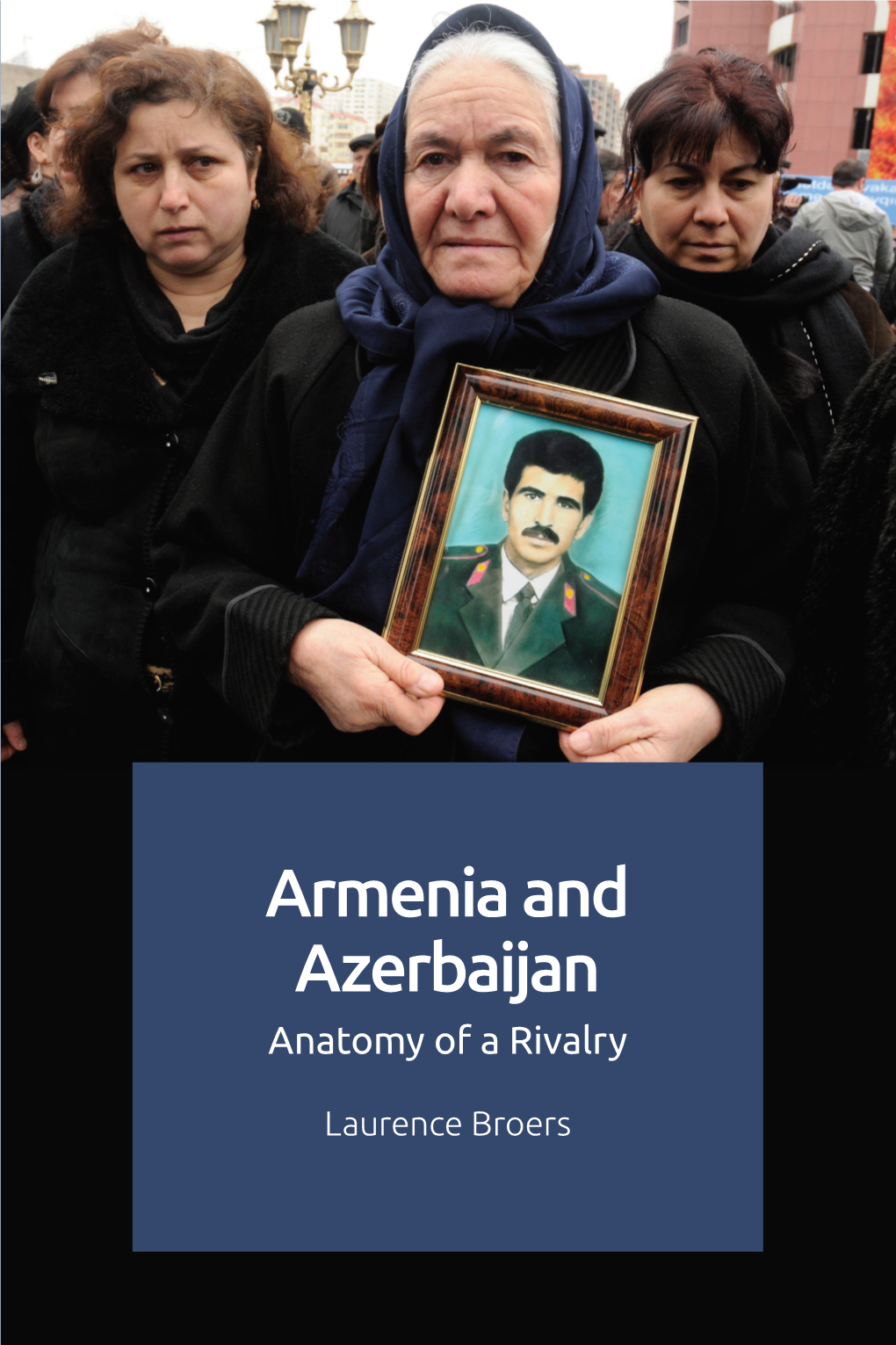

Armenia and Azerbaijan for Control Over the Contested Territory of Nagorny Karabakh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study of Kufic Script in Islamic Calligraphy and Its Relevance To

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1999 A study of Kufic script in Islamic calligraphy and its relevance to Turkish graphic art using Latin fonts in the late twentieth century Enis Timuçin Tan University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Tan, Enis Timuçin, A study of Kufic crs ipt in Islamic calligraphy and its relevance to Turkish graphic art using Latin fonts in the late twentieth century, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 1999. http://ro.uow.edu.au/ theses/1749 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. A Study ofKufic script in Islamic calligraphy and its relevance to Turkish graphic art using Latin fonts in the late twentieth century. DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by ENiS TIMUgiN TAN, GRAD DIP, MCA FACULTY OF CREATIVE ARTS 1999 CERTIFICATION I certify that this work has not been submitted for a degree to any university or institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by any other person, expect where due reference has been made in the text. Enis Timucin Tan December 1999 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I acknowledge with appreciation Dr. Diana Wood Conroy, who acted not only as my supervisor, but was also a good friend to me. I acknowledge all staff of the Faculty of Creative Arts, specially Olena Cullen, Liz Jeneid and Associate Professor Stephen Ingham for the variety of help they have given to me. -

Armenophobia in Azerbaijan

Հարգելի՛ ընթերցող, Արցախի Երիտասարդ Գիտնականների և Մասնագետների Միավորման (ԱԵԳՄՄ) նախագիծ հանդիսացող Արցախի Էլեկտրոնային Գրադարանի կայքում տեղադրվում են Արցախի վերաբերյալ գիտավերլուծական, ճանաչողական և գեղարվեստական նյութեր` հայերեն, ռուսերեն և անգլերեն լեզուներով: Նյութերը կարող եք ներբեռնել ԱՆՎՃԱՐ: Էլեկտրոնային գրադարանի նյութերն այլ կայքերում տեղադրելու համար պետք է ստանալ ԱԵԳՄՄ-ի թույլտվությունը և նշել անհրաժեշտ տվյալները: Շնորհակալություն ենք հայտնում բոլոր հեղինակներին և հրատարակիչներին` աշխատանքների էլեկտրոնային տարբերակները կայքում տեղադրելու թույլտվության համար: Уважаемый читатель! На сайте Электронной библиотеки Арцаха, являющейся проектом Объединения Молодых Учёных и Специалистов Арцаха (ОМУСA), размещаются научно-аналитические, познавательные и художественные материалы об Арцахе на армянском, русском и английском языках. Материалы можете скачать БЕСПЛАТНО. Для того, чтобы размещать любой материал Электронной библиотеки на другом сайте, вы должны сначала получить разрешение ОМУСА и указать необходимые данные. Мы благодарим всех авторов и издателей за разрешение размещать электронные версии своих работ на этом сайте. Dear reader, The Union of Young Scientists and Specialists of Artsakh (UYSSA) presents its project - Artsakh E-Library website, where you can find and download for FREE scientific and research, cognitive and literary materials on Artsakh in Armenian, Russian and English languages. If re-using any material from our site you have first to get the UYSSA approval and specify the required data. We thank all the authors -

Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus

STATUS AND PROTECTION OF GLOBALLY THREATENED SPECIES IN THE CAUCASUS CEPF Biodiversity Investments in the Caucasus Hotspot 2004-2009 Edited by Nugzar Zazanashvili and David Mallon Tbilisi 2009 The contents of this book do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of CEPF, WWF, or their sponsoring organizations. Neither the CEPF, WWF nor any other entities thereof, assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, product or process disclosed in this book. Citation: Zazanashvili, N. and Mallon, D. (Editors) 2009. Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus. Tbilisi: CEPF, WWF. Contour Ltd., 232 pp. ISBN 978-9941-0-2203-6 Design and printing Contour Ltd. 8, Kargareteli st., 0164 Tbilisi, Georgia December 2009 The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank. This book shows the effort of the Caucasus NGOs, experts, scientific institutions and governmental agencies for conserving globally threatened species in the Caucasus: CEPF investments in the region made it possible for the first time to carry out simultaneous assessments of species’ populations at national and regional scales, setting up strategies and developing action plans for their survival, as well as implementation of some urgent conservation measures. Contents Foreword 7 Acknowledgments 8 Introduction CEPF Investment in the Caucasus Hotspot A. W. Tordoff, N. Zazanashvili, M. Bitsadze, K. Manvelyan, E. Askerov, V. Krever, S. Kalem, B. Avcioglu, S. Galstyan and R. Mnatsekanov 9 The Caucasus Hotspot N. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents 1. Social Economic Background & Current Indicators of Syunik Region...........................2 2. Key Problems & Constraints .............................................................................................23 Objective Problems ...................................................................................................................23 Subjective Problems..................................................................................................................28 3. Assessment of Economic Resources & Potential ..............................................................32 Hydropower Generation............................................................................................................32 Tourism .....................................................................................................................................35 Electronics & Engineering ........................................................................................................44 Agriculture & Food Processing.................................................................................................47 Mineral Resources (other than copper & molybdenum)...........................................................52 Textiles......................................................................................................................................55 Infrastructures............................................................................................................................57 -

3. Energy Reserves, Pipeline Routes and the Legal Regime in the Caspian Sea

3. Energy reserves, pipeline routes and the legal regime in the Caspian Sea John Roberts I. The energy reserves and production potential of the Caspian The issue of Caspian energy development has been dominated by four factors. The first is uncertain oil prices. These pose a challenge both to oilfield devel- opers and to the promoters of pipelines. The boom prices of 2000, coupled with supply shortages within the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), have made development of the resources of the Caspian area very attractive. By contrast, when oil prices hovered around the $10 per barrel level in late 1998 and early 1999, the price downturn threatened not only the viability of some of the more grandiose pipeline projects to carry Caspian oil to the outside world, but also the economics of basic oilfield exploration in the region. While there will be some fly-by-night operators who endeavour to secure swift returns in an era of high prices, the major energy developers, as well as the majority of smaller investors, will continue to predicate total production costs (including carriage to market) not exceeding $10–12 a barrel. The second is the geology and geography of the area. The importance of its geology was highlighted when two of the first four international consortia formed to look for oil in blocks off Azerbaijan where no wells had previously been drilled pulled out in the wake of poor results.1 The geography of the area involves the complex problem of export pipeline development and the chicken- and-egg question whether lack of pipelines is holding back oil and gas pro- duction or vice versa. -

Development Project Ideas Goris, Tegh, Gorhayk, Meghri, Vayk

Ministry of Territorial Administration and Development of the Republic of Armenia DEVELOPMENT PROJECT IDEAS GORIS, TEGH, GORHAYK, MEGHRI, VAYK, JERMUK, ZARITAP, URTSADZOR, NOYEMBERYAN, KOGHB, AYRUM, SARAPAT, AMASIA, ASHOTSK, ARPI Expert Team Varazdat Karapetyan Artyom Grigoryan Artak Dadoyan Gagik Muradyan GIZ Coordinator Armen Keshishyan September 2016 List of Acronyms MTAD Ministry of Territorial Administration and Development ATDF Armenian Territorial Development Fund GIZ German Technical Cooperation LoGoPro GIZ Local Government Programme LSG Local Self-government (bodies) (FY)MDP Five-year Municipal Development Plan PACA Participatory Assessment of Competitive Advantages RDF «Regional Development Foundation» Company LED Local economic development 2 Contents List of Acronyms ........................................................................................................................ 2 Contents ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Structure of the Report .............................................................................................................. 5 Preamble ..................................................................................................................................... 7 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 9 Approaches to Project Implementation .................................................................................. -

Statement by H.E. Mr. Ilham Aliyev, President of The

STATEMENT BY H.E. MR. ILHAM ALIYEV, PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF AZERBAIJAN MEETING OF HEADS OF STATE AND GOVERNMENT “FINANCING THE 2030 AGENDA FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT IN THE ERA OF COVID-19 AND BEYOND” 29 September 2020 Mr. Secretary-General, Distinguished Heads of State and Government, Azerbaijan attaches great importance to the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals. Our success was reflected in the “Sustainable Development Report 2020”, where Azerbaijan ranks 54th among 166 countries in the Sustainable Development Goals Index. Azerbaijan’s GDP tripled in the last 17 years. The external public debt of Azerbaijan is one of the lowest in the world. Azerbaijan has the lowest external debt among the oil exporting countries. Foreign Exchange Reserves of Azerbaijan exceed the external public debt by 6 times. Azerbaijan places a special emphasis on the equal distribution of energy revenues between current and the future generations. To this end, the State Oil Fund was established. The assets of the Fund currently exceed the GDP of the country. Azerbaijan has achieved one of the highest income equality levels. As a result of the Armenian occupation more than 1 million Azerbaijanis became refugees and internally displaced persons. About 8 billion Azerbaijani manats amounting to nearly 5 billion USD has been allocated for addressing needs of this vulnerable group. Azerbaijan itself became a donor country. Overall, Azerbaijan provided financial and humanitarian assistance to nearly 120 countries during the last 15 years. Despite the decrease in the state revenues during the pandemic period the government has allocated fund around 3% of GDP to the protection of jobs, economic growth and the public health. -

Republic of Nagorno Karabakh (Artsakh)

Armenian National Committee of America 1711 N Street NW | Washington DC 20036 | Tel: (202) 775-1918 | Fax: (202) 775-1918 [email protected] | www.anca.org Republic of Nagorno Karabakh (Artsakh) 1) Republic of Nagorno Karabakh (Artsakh) The Republic of Nagorno Karabakh (Artsakh) is an integral part of historic Armenia that was arbitrarily carved out in 1921 by Joseph Stalin and placed under Soviet Azerbaijani administration, but with autonomous status, as part of the Soviet divide- and-conquer strategy in the Caucasus. Nagorno Karabakh has never been part of an independent Azerbaijani state. Declassified Central Intelligence Agency reports confirm that Nagorno Karabakh is historically Armenian and maintained even more autonomy than the rest of Armenia through the centuries.1 To force Christian Armenians to be ruled by Muslim Azerbaijan would be to sanction Joseph Stalin's policies and ensure continued instability in the region. During seven decades of Soviet Azerbaijani rule, the Armenian population of Nagorno Karabakh was subjected to discriminatory policies aimed at its removal. Even after these efforts to force Armenians from their land, Nagorno Karabakh's pre-war population in 1988 was over 80% Armenian. In the late 1980's, the United States welcomed Nagorno Karabakh's historic challenge to the Soviet system and its leadership in sparking democratic movements in the Baltics and throughout the Soviet empire. Following a peaceful demand by Karabakh's legislative body to reunite the region with Armenia in 1988, Azerbaijan launched an ethnic cleansing campaign against individuals of Armenian descent with pogroms against civilians in several towns, including Sumgait and Baku. -

Political Leadership After Communism

POLITICAL LEADERSHIP AFTER COMMUNISM TIMOTHY J. COLTON MORRIS AND ANNA FELDBERG PROFESSOR OF GOVERNMENT AND RUSSIAN STUDIES, HARVARD UNIVERSITY Abstract: Political scientists have paid little attention to the role of leadership. This article suggests a way to think systematically about leaders’ contributions in the former Soviet Union by examining their ability to achieve their own goals and the impact they have. The fifteen countries provide a wide range of variation on the dependent variable. hat have we learned about political leadership in the post-communist Wworld? It is fair to say that it is not as much as we have picked up about a host of other ordering issues, among them political economy, institutional design, ethnic conflict, and public opinion and elections. Considering the significance of the magnitude of the topic, we have not learned nearly enough. There are students of post-communist politics who tend to accept the importance of the theme and those who, embracing structural approaches, tend not to. A majority in the scholarly community fall into the former camp. “Leadership matters,” is how they often put it. “It matters a lot. Why, just look at Gorbachev’s role, and also Yeltsin’s, and then there is Putin, and [fill in the blanks].” However, the majority have seldom thought leadership important enough to make it a primary object of their research. Leaders have figured in a handful of serious political biographies, in natu- ralistic roles in many studies of other topics, in several studies of ideas in politics, and in all manner of op-eds du jour. -

2017 Newsletter

NEWSLETTER FALL 2017 Liminality & ISSUE 11 Memorial Practices IN 3 Notes from the Director THIS 4 Faculty News and Updates ISSUE: 6 Year in Review: Orphaned Fields: Picturing Armenian Landscapes Photography and Armenian Studies Orphans of the Armenian Genocide Eighth Annual International Graduate Student Workshop 11 Meet the Manoogian Fellows NOTES FROM 14 Literature and Liminality: Exploring the Armenian in-Between THE DIRECTOR Armenian Music, Memorial Practices and the Global in the 21st 14 Kathryn Babayan Century Welcome to the new academic year! 15 International Justice for Atrocity Crimes - Worth the Cost? Over the last decade, the Armenian represents the first time the Armenian ASP Faculty Armenian Childhood(s): Histories and Theories of Childhood and Youth Studies Program at U-M has fostered a Studies Program has presented these 16 Hakem Al-Rustom in American Studies critical dialogue with emerging scholars critical discussions in a monograph. around the globe through various Alex Manoogian Professor of Modern workshops, conferences, lectures, and This year we continue in the spirit of 16 Multidisciplinary Workshop for Armenian Studies Armenian History fellowships. Together with our faculty, engagement with neglected directions graduate students, visiting fellows, and in the field of Armenian Studies. Our Profiles and Reflections Kathryn Babayan 17 postdocs we have combined our efforts two Manoogian Post-doctoral fellows, ASP Fellowship Recipients Director, Armenian to push scholarship in Armenian Studies Maral Aktokmakyan and Christopher Studies Program; 2017-18 ASP Graduate Students in new directions. Our interventions in Sheklian, work in the fields of literature Associate Professor of the study of Armenian history, literature, and anthropology respectively. -

Country Profile – Azerbaijan

Country profile – Azerbaijan Version 2008 Recommended citation: FAO. 2008. AQUASTAT Country Profile – Azerbaijan. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Rome, Italy The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Except where otherwise indicated, material may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that appropriate acknowledgement of FAO as the source and copyright holder is given and that FAO’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services is not implied in any way. All requests for translation and adaptation rights, and for resale and other commercial use rights should be made via www.fao.org/contact-us/licencerequest or addressed to [email protected]. FAO information products are available on the FAO website (www.fao.org/ publications) and can be purchased through [email protected]. -

Rethinking the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict: Identity, Politics, Scholarship

University of San Diego Digital USD School of Peace Studies: Faculty Scholarship School of Peace Studies 2010 Rethinking the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict: Identity, Politics, Scholarship Philip Gamaghelyan Phd University of San Diego, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.sandiego.edu/krocschool-faculty Part of the Peace and Conflict Studies Commons Digital USD Citation Gamaghelyan, Philip Phd, "Rethinking the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict: Identity, Politics, Scholarship" (2010). School of Peace Studies: Faculty Scholarship. 1. https://digital.sandiego.edu/krocschool-faculty/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Peace Studies at Digital USD. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Peace Studies: Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Digital USD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rethinking the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict: Identity, Politics, Scholarship Phil Gamaghelyan* Imagine Center for Conflict Transformation, 16 Whites Avenue, Suite 51, Watertown, MA 02472 USA (E-mail: [email protected]) Received 5 August 2008; accepted 18 May 2009 Abstract This article builds on the author’s research concerning the role of collective memory in identity- based conflicts, as well as his practical work as the co-director of the Imagine Center for Conflict Transformation and as a trainer and facilitator with various Azerbaijani-Armenian dialogue initiatives. It is not a comprehensive study of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, but presents a general overview of the Nagorno-Karabakh peace process, what has contributed to its failure, and which areas require major rethinking of conventional approaches. The discussion does not intend to present readers with a set of conclusions, but to provide suggestions for further critical research.