CONCEALED GAZES the Closed Balconies of Lima and How They Affected Women's Relationship to the Public Space and Public Sphere

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fabuleux Pérou

Le meilleur du Pérou Pour marcher dans les pas des civilisations précolombiennes Le Museo Nacional de Arqueología, cérémoniel, religieux et astronomique Antropología e Historia del Perú de des Nascas, ainsi que les énigmatiques Lima, qui passe brillamment en revue des lignes de Nasca (p. 30) siècles d’histoire et permet de s’initier aux nombreuses civilisations qui ont foulé le Chan Chan, la plus vaste cité précolom- sol péruvien (p. 17) bienne d’Amérique, abandonnée par les Chimús aux mains des Incas (p. 91) Les ruines de Caral (p. 77), Sechín (p. 77) et Chavín (p. 82), qui La célèbre citadelle de Machu Picchu témoignent encore aujourd’hui de civilisa- (p. 69) non loin de Cusco (p. 58), tions parmi les plus anciennes d’Amérique capitale des Incas et centre de l’Empire et d’un réseau de sites parsemés au-dessus La visite des ruines de Wari avec un guide, de la ville (Sacsayhuamán, Qenko, pour comprendre l’Empire wari (huari), Tambo Machay, Chinchero) et dans la dans la région d’Ayacucho (p. 110) Vallée sacrée (Pisac, Ollantaytambo) Les Huacas del Sol y de la Luna (p. 89), Le Museo Tumbas Reales de Sipán, qui ou temples du Soleil et de la Lune, bril- abrite les trésors trouvés lors de la décou- lants témoins de l’histoire de la culture verte de la tombe du Señor de Sipán Mochica et d’autres chefs de la nation Mochica (p. 97) Le site archéologique de Cahuachi (p. 28), vestige de ce qui fut un centre Pour revivre l’époque coloniale Trujillo, vaste oasis dans le désert côtier Les édifices coloniaux élevés sur les et agréable cité coloniale (p. -

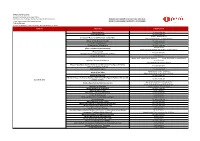

Horario De Atención De Atractivos Turísticos

IPERÚ Lima Aeropuerto Aeropuerto Internacional Jorge Chávez Mezzanine Sur, Embarque Nacional y Llegadas Internacionales HORARIO DE ATENCIÓN DE ATRACTIVOS TURÍSTICOS E-mail: [email protected] T (51-1) 574 8000 SEMANA SANTA 2017 Horario de atención: Lunes a domingo , incluido feriados -24 horas DISTRITO ATRACTIVO DESCRIPCIÓN DIRECCIÓN ACCESO TELÉFONO TARIFA DE INGRESO JUEVES 13 VIERNES 14 SÁBADO 15 DOMINGO 16 ACCESO PARA DISCAPACITADOS OBSERVACIONES Horario de atención normal: Horario de atención normal: Horario de atención normal: Horario de atención normal: Ocupa el mismo lugar donde se encontraba la primera iglesia mayor *Adulto nacional / *Museo: L-V 9:00-17:00 hrs / S 10:00- *Museo: L-V 9:00-17:00 hrs / S 10:00- *Museo: L-V 9:00-17:00 hrs / S 10:00- *Museo: L-V 9:00-17:00 hrs / S 10:00- Cuenta con facilidades en el ingreso de Lima. El interior es austero, aunque alberga verdaderas joyas Plaza Mayor de Guiado opcional, no tienen un precio extranjero y estudiantes 13:00 hrs / D 13:00- 17:00 hrs. *Misas: 13:00 hrs / D 13:00- 17:00 hrs. *Misas: 13:00 hrs / D 13:00- 17:00 hrs. *Misas: 13:00 hrs / D 13:00- 17:00 hrs. *Misas: (rampas) las que se encuentran ubicada históricas, como la sillería del coro de Baltasar Noguera, diversos Lima (Esquina de Jr. (01) 427-9647 / 426- establecido para los guías; los idiomas Catedral de Lima Taxi extranjeros : S/ 10.00 *Niño S 09:00 - 10:00 y D 11:00 - 12:00hrs. S 09:00 - 10:00 y D 11:00 - 12:00hrs. -

Painting As a Form of Communication in Colonial Central Andes

Painting as a Form of Communication in Colonial Central Andes Variations on the Form of Ornamental Art in Early World Society Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Kultur- und Sozialwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Luzern vorgelegt von Fernando Valenzuela von Santiago (Chile) Eingereicht am: 7. September 2009 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Rudolf Stichweh Zweitgutachterin: Prof. Dr. Cornelia Bohn Originaldokument gespeichert auf dem Dokumentserver der ZHB Luzern http://www.zhbluzern.ch Dieses Werk ist unter einem Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 Switzerland Lizenzvertrag lizenziert. Um die Lizenz anzusehen, gehen Sie bitte zu http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/ch/ oder schicken Sie einen Brief an Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California 94105, USA. Eine Kurzform der in Anspruch genommenen Rechte finden Sie auch auf der nachfolgenden Seite dieses Dokuments. Urheberrechtlicher Hinweis Dieses Dokument steht unter einer Lizenz der Creative Commons Namensnennung-Keine kommerzielle Nutzung-Keine Bearbeitung 2.5 Schweiz http://creativecommons.org/ Sie dürfen: das Werk bzw. den Inhalt vervielfältigen, verbreiten und öffentlich zugänglich machen Zu den folgenden Bedingungen: Namensnennung — Sie müssen den Namen des Autors/Rechteinhabers in der von ihm festgelegten Weise nennen. Keine kommerzielle Nutzung — Dieses Werk bzw. dieser Inhalt darf nicht für kommerzielle Zwecke verwendet werden. Keine Bearbeitung — Dieses Werk bzw. dieser Inhalt darf nicht bearbeitet, abgewandelt oder in anderer Weise verändert werden. Wobei gilt: Verzichtserklärung — Jede der vorgenannten Bedingungen kann aufgehoben werden, sofern Sie die ausdrückliche Einwilligung des Rechteinhabers dazu erhalten. • Public Domain (gemeinfreie oder nicht-schützbare Inhalte) — Soweit das Werk, der Inhalt oder irgendein Teil davon zur Public Domain der jeweiligen Rechtsordnung gehört, wird dieser Status von der Lizenz in keiner Weise berührt. -

Index Du Guide

336 Index Les numéros de page en gras renvoient à des cartes. A Ayacucho (de Lima aux Andes centrales) 307, 308 Abancay (de Lima aux Andes centrales) 310 achats 314 Accès au pays 49 hébergement 312, 313 Achats 53 restaurants 313, 313 Acora (Lac Titicaca et ses environs) 187 sorties 314 Activités de plein air 91 alpinisme 250 B descente de rivière 140, 164, 220, 250, 328 Bagages 60 dune buggy 140 Baignade 91 équitation 141, 166, 220, 277 Bains thermaux (Yura) 160 escalade 250 Baños del Inca (Cajamarca et ses environs) 294 pêche 277 Baños de Monterrey (département d’Ancash) 246 planche à voile 277 Baños La Calera (Arequipa à la frontière chilienne) 161 randonnée pédestre 166, 220, 250, 328 Banques 57 saut à l’élastique 220 Barranca (département d’Ancash) 242 surf 141, 166, 277 hébergement 252 surf des sables 140 Barranco (Lima) 111 survol en ballon dirigeable 220 hébergement 119 vélo 166, 220, 251 restaurants 123 Adobe 269 Bateau 52 Aéroports internationaux 49 Belén, quartier de (Iquitos) 324 Aeropuerto Alejandro Velasco Astete (Cusco) 49 Bitti, Bernado 40 Aeropuerto Jorge Chávez (Lima) 49 Bodega Alvárez (Ica) 136 Agences d’excursions 55 Boissons alcoolisées 66 Aguas Calientes (Cusco et ses environs) 212 Boissons non alcoolisées 66 hébergement 230, 230 Boleto turístico 203 restaurants 230, 234 Bolívar, Simón 32 Alegría, Ciro 43 Bosque Olivar (San Isidro) 108 Algarobo 19 Bryce Echenique, Alfredo 42 Alligator 15 Bureaux de change 58 Alpaga 16 Alpinisme C département d’Ancash 250 Cabanaconde (Arequipa à la frontière chilienne) 162 Ambassades -

Catedral De Lima Plaza Mayor De Lima

IPERÚ Lima Aeropuerto Aeropuerto Internacional Jorge Chávez Mezzanine Sur, Embarque Nacional y Llegadas Internacionales E-mail: [email protected] T (51-1) 574 8000 Horario de atención: Lunes a domingo , incluido feriados -24 horas DISTRITO ATRACTIVO DIRECCIÓN TELÉFONO TARIFA DE INGRESO JUEVES 29 VIERNES 30 SÁBADO 01 DOMINGO 02 Plaza Mayor de Lima (Esquina *Adulto nacional / extranjero y estudiantes extranjeros : L-V 9:00-17:00 hrs / S 9:00-13:00 hrs / D 13:00- 17:00 Horario de atención normal: Museo: No habrá atención Museo: No habrá atención Catedral de Lima de Jr. Huallaga y Jr. (01) 427-9647 / 426-7056 S/ 10.00 *Niño nacional y escolares: S/ 2.00 (hasta los 12 hrs. L-V 9:00-17:00 hrs / S 9:00-13:00 hrs / D 13:00- 17:00 CarabayaK) años) Misas: D 11:00 - 12:00 hrs. hrs. 09:30-10:30 hrs. 09:30-10:30 hrs. Palacio de Gobierno Plaza Mayor de Lima 311-3908-3113900 anexo 378 Ingreso gratuito No habrá atención No habrá atención (Previa inscripción) (Previa inscripción) Adultos: S/ 10.00 Museo: L-D 9:00-20:00 hrs . Museo: L-D 9:00-20:00 hrs Museo: L-D 9:00-20:00 hrs Convento y Museo de San Francisco - (01) 427-1381 Museo: L-D 9:00-20:00 hrs. Jr. Ancash cdra. 3 y Jr. Lampa Universitarios: S/ 5.00 Iglesia: L-D 07:00-11:00 hrs. y 16:00-20:00 hrs. Iglesia: L-D 07:00-11:00 hrs. y 16:00-20:00 hrs. -

Horario De Atencion De Atractivos

IPERÚ Lima Aeropuerto Aeropuerto Internacional Jorge Chávez HORARIO DE ATENCION DE ATRACTIVOS TURISTICOS DE LIMA Y CALLAO Sala de Embarque Nacional, Llegadas Internacionales y Mezzanine "FERIADO 28 Y 29 DE JULIO - FIESTAS PATRIAS" [email protected] (01) 574-8000 24 horas ACCESO DESDE HORARIO DE ATENCIÓN ACCESO PARA DISTRITO ATRACTIVO DESCRIPCIÓN DIRECCIÓN EL TELÉFONO TARIFA DE INGRESO HORARIO NORMAL OBSERVACIONES DISCAPACITADOS AEROPUERTO LUNES 28 MARTES 29 Ocupa el mismo lugar donde se encontraba la primera iglesia mayor de Adulto nacional y extranjero: S/.10.00 Lima. El interior es austero, aunque Niño nacional y extranjero (hasta los 10 Cuentan con facilidades en el alberga verdaderas joyas históricas, como Plaza Mayor de Lima años): S/.2.00 Lunes a viernes 09:00 a 17:00 hrs. ingreso (rampas) ubicado en la sillería del coro de Baltasar Noguera, 427-9647 Catedral de Lima (Esquina de Jr. Huallaga con Taxi Guiado opcional, no tienen un precio Sábado 10:00 a 13:00 hrs. No habrá atención No habrá atención Jr. Junín y Jr. Carabaya. Ninguna diversos altares laterales y los restos de 426-7056 Jr. Carabaya) establecido, los guías manejan el idioma Domingo 13:00 a 17:00 hrs. Cuentan con SS.HH. para Francisco Pizarro. Además, puede inglés, francés, portugués, italiano y discapacitados. visitarse el Museo de Arte Religioso, con español. una importante colección de lienzos, esculturas, cálices y casullas. Construido en 1535 por orden de Francisco Pizarro, Desde entonces, el lugar es centro del poder político del Perú. En la década de los años 20 fue Sábado y domingo 09:00 a 10:30 hrs. -

Rico Camps, Daniel. Antecedentes Y Valoración Del Patrimonio Cultural Del Perú

This is the published version of the bachelor thesis: Narro Carrasco, Jorge Luis; Rico Camps, Daniel. Antecedentes y valoración del patrimonio cultural del Perú. 2011. This version is available at https://ddd.uab.cat/record/77028 under the terms of the license Antecedentes y Valoración del Patrimonio Cultural del Perú Tesina para optar la Suficiencia Investigadora del Programa de Doctorado en Humanidades Autor: Jorge Luis Narro Carrasco Director: Dr. Daniel Rico Camps INDICE Presentación Breve Visión 8 Introducción 10 Primera Parte I. Valoración del Patrimonio Cultural del Perú y lo más importante del Patrimonio Cultural reconocido 1. Precedentes del Patrimonio Cultural en el Perú 12 2. Valoración del Patrimonio Cultural 16 3. Patrimonio Cultural más importante reconocido a la actualidad 20 3.1 Arqueológico 20 3.1.1 Zonas Arqueológicas y Sitios de Excavación: 20 a) Huaca Rajada. Tumbas Reales del Señor de Sipán 21 b) El Señor de Sicán. Batan Grande Lambayeque 21 c) Chan Chan. Trujillo. La Libertad 22 d) La Dama de Ampato. Arequipa 23 e) Ciudadela de Caral. Lima 23 3.1.2 Zonas Arqueológicas Turísticas 23 a) Macchu Picchu 23 b) Las Líneas de Nazca 24 3.2 Histórico - Artístico 24 a) Zonas Monumentales 24 b) Ambientes Urbano Monumentales 24 c) Monumentos Históricos Artísticos 25 3.3 Bibliográfico y Monumental 26 a) Patrimonio Bibliográfico 26 b) Patrimonio Documental 27 2 c) Patrimonio Artístico 27 d) Patrimonio Fotográfico 28 e) Patrimonio Filmográfico 30 3.4 Patrimonio cultural de la humanidad 30 3.5 En el campo del Folklore 31 3.6 En el campo de la Música 32 Segunda Parte II. -

IPERÚ Lima Aeropuerto Aeropuerto Internacional Jorge Chávez

IPERÚ Lima Aeropuerto Aeropuerto Internacional Jorge Chávez Mezzanine Sur, Embarque Nacional y Llegadas Internacionales E-mail: [email protected] T (51-1) 574 8000 Horario de atención: Lunes a domingo , incluido feriados -24 horas DIA DE TODOS LOS SANTOS DISTRITO ATRACTIVO MIÉRCOLES 01 DE NOVIEMBRE Catedral de Lima No habrá atención del museo. Sólo habrá misa de 11:00 a 12:00 hrs. Palacio de Gobierno No habrá atención dado que no realizan visitas los días miércoles. Palacio Municipal Se han suspendido las visitas hasta nuevo aviso Convento y Museo de Museo: 9:00-20:00 hrs San Francisco y Iglesia: 07:00-11:00 hrs. y 16:00-20:00 hrs. Catacumbas Atenderán en horario normal. Museo de Sitio Bodega y Quadra No habrá atención. 09:00-17:00 hrs. Casa de la Cercado de Lima Atenderán en horario normal. Gastronomía Exposición Museo Nacional Afroperuano No atienden feriados. - Casa de las Trece Monedas Museo de la Inquisición y del Cerrado por mantenimiento hasta 2018 Congreso Iglesia y Convento de 9:30-18:00 hrs Santo Domingo Torre (mayores de 18 años): 11:00 – 16:00 hrs (Museo) Atenderán en horario normal. VISITA DIURNA Iglesia y Convento de Santo Domingo No habrá recorridos nocturnos. (Museo) VISITA NOCTURNA Museo Central (Ex Museo del Banco No habrá atención. Central de Reserva del Perú) Horario del tour nocturno: Cementerio General Cuatro veces al mes (las quincenas y fin de mes) los días Viernes Presbítero Matías y Sábados de 19:00-22:00hrs. Maestro Horario de atención por feriados: VISITA NOCTURNA Atenderán en horario normal . -

IPERÚ Lima Aeropuerto

IPERÚ Lima Aeropuerto Aeropuerto Internacional Jorge Chávez Mezzanine Sur, Embarque Nacional y Llegadas Internacionales HORARIO DE ATENCIÓN DE ATRACTIVOS TURÍSTICOS E-mail: [email protected] FERIADO INMACULADA CONCEPCIÓN - 08 DICIEMBRE T (51-1) 574 8000 Horario de atención: Lunes a domingo , incluido feriados -24 horas DISTRITO ATRACTIVO VIERNES 08 DIC Catedral de Lima No habrá atención Palacio de Gobierno No habrá atención Museo: 9:00-20:00 hrs Convento y Museo de San Francisco - Catacumbas. Iglesia:07:00-11:00 hrs. y 16:00-20:00 hrs Museo de Sitio Bodega y Quadra No habrá atención Casa de la Gastronomía 09:00-17:00 hrs Museo Nacional Afroperuano No habrá atención 9:30-18:00 hrs Iglesia y Convento de Santo Domingo Visitas a la torre (mayores de 18 años): 11:00–16:00 hrs Museo Central No habrá atención. (Ex Museo del Banco Central de Reserva del Perú) Parque de la Muralla 9:00-20:30 hrs. Iglesia: 8:00 –13:00 y 16:00-21:00 hrs. Misas: 8:00-13:00 hrs y 16:00-20:00 Iglesia y Convento de La Merced hrs.(cada hora) *Se puede ingresar solo a la Basílica Museo Arqueológico Josefina Ramos de Cox del Instituto Riva Agüero (Pontificia No habrá atención. Universidad Católica del Perú) Casa Museo O' Higgins No habrá atención. 08:00-12:00 y 17:00 – 19:00 hrs. Iglesia de San Pedro Misas: 08:00, 09:00, 12:00, 18:00, 19:30 hrs. Palacio de Torre Tagle No habrá atención Museo de Artes y Tradiciones Populares del Instituto Riva Agüero (Pontificia Universidad No habrá atención Cercado de Lima Católica del Perú) Iglesia: 8:00-12:00 hrs y 17:00-20:00 hrs Iglesia y Monasterio de Santa Rosa de Lima Jardin: 9:00-13:00 hrs y de 15:00-18:00 hrs. -

Atractivos Semana Santa.Pdf

IPERÚ Lima Aeropuerto Aeropuerto Internacional Jorge Chávez Mezzanine Sur, Embarque Nacional y Llegadas Internacionales HORARIO DE ATENCIÓN DE ATRACTIVOS TURÍSTICOS E-mail: [email protected] T (51-1) 574 8000 SEMANA SANTA 2017 Horario de atención: Lunes a domingo , incluido feriados -24 horas DISTRITO ATRACTIVO DIRECCIÓN TELÉFONO TARIFA DE INGRESO JUEVES 13 VIERNES 14 SÁBADO 15 DOMINGO 16 *Adulto nacional / extranjero y estudiantes extranjeros : Plaza Mayor de Lima (Esquina Museo: No habrá atención Museo: No habrá atención Museo: No habrá atención Museo: No habrá atención Catedral de Lima (01) 427-9647 / 426-7056 S/ 10.00 *Niño nacional y escolares: S/ 2.00 (hasta los 12 de Jr. Huallaga y Jr. Carabaya) Misas: según programación Misas: según programación Misas: según programación Misas: según programación años) 09:30-10:30 h. 311-3908-3113900 anexo 9:30-10:30 h. Palacio de Gobierno Plaza Mayor de Lima Ingreso gratuito No habrá atención No habrá atención (Previa inscripción). 378 (Previa inscripción). Adultos: S/ 10.00 Museo: 9:00- 20:00 h. Museo: 9:00- 20:00 h. Convento y Museo de San (01) 427-1381 Museo: 9:00- 20:00 h Jr. Ancash cdra. 3 y Jr. Lampa Universitarios: S/ 5.00 No habrá atención Iglesia: 07:00-11:00 hrs y de 16:00-20:00 Iglesia: 07:00-11:00 h y de 16:00-20:00 Francisco - Catacumbas. anexo museo 3 Iglesia: 07:00-11:00 h y de 16:00-20:00 h Niños o escolares: S/ 1.00 h. h. (01) 428-2390 Adultos: S/ 4.00 Museo de Sitio Bodega y Quadra Jr. -

Libro De Lima .Indd

LIMA 1 2 B PROGRAMA DE GOBIERNO REGIONAL DE LIMA METROPOLITANA PROYECTO FORTALECIMIENTO DE LA IDENTIDAD CULTURAL DE LIMA METROPOLITANA 1 PATRIMONIO CULTURAL DE LA HUMANIDAD 2 LIMAPATRIMONIO CULTURAL DE LA HUMANIDAD 3 4 5 6 7 Salón de Recepciones - Palacio Municipal de Lima / Reception Hall - Municipal Palace of Lima Interior - Palacio Municipal de Lima, página 6 - 7 / Interior - Municipal Palace of Lima, page 6 - 7 Frontis del Palacio Municipal de Lima, página 4 - 5 / Façade of the Municipal Palace of Lima, page 4 - 5 8 9 10 ÍNDICE / TABLE OF CONTENTS PRESENTACIÓN / INTRODUCTION 13 PRÓLOGO / PROLOGUE 15 ATRACTIVOS TURÍSTICOS / TOURIST ATTRACTIONS 19 IGLESIAS Y CONVENTOS / CHURCHES AND MONASTERIES 81 CASAS SEÑORIALES / THE NOBLE HOUSES 105 MUSEOS / MUSEUMS 131 CENTROS ARQUEOLÓGICOS PREHISPÁNICOS 163 PRE-HISPANIC ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES DISTRITOS TURÍSTICOS / TOURIST DISTRICTS 179 LIMA GASTRONÓMICA / CULINARY LIMA 219 CONSEJO EDITORIAL / EDITORIAL STAFF 227 AGRADECIMIENTOS / ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 229 11 12 PRESENTACIÓN PRESENTATION Lima, considerada por la Unesco como Lima, a city that is listed as a Cultural Heritage Patrimonio Cultural de la Humanidad des- of Humanity by UNESCO since 1991, is now on de 1991, se muestra de puertas al futuro con the threshold of the future, accompanied by its su tradición y mirada firme en el horizonte. rich traditions with its gaze firmly fixed on the Convertida en una gran ciudad cosmopolita a horizon. This book offers insights into some orillas del Pacífico, presenta en este libro lo me- of the most exciting tourist attractions of what jor de sus atractivos turísticos. has become a cosmopolitan city, on the shores of the great Pacific.