Success and Failure of Cyzenis Albicans in Controlling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No Slide Title

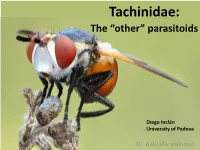

Tachinidae: The “other” parasitoids Diego Inclán University of Padova Outline • Briefly (re-) introduce parasitoids & the parasitoid lifestyle • Quick survey of dipteran parasitoids • Introduce you to tachinid flies • major groups • oviposition strategies • host associations • host range… • Discuss role of tachinids in biological control Parasite vs. parasitoid Parasite Life cycle of a parasitoid Alien (1979) Life cycle of a parasitoid Parasite vs. parasitoid Parasite Parasitoid does not kill the host kill its host Insects life cycles Life cycle of a parasitoid Some facts about parasitoids • Parasitoids are diverse (15-25% of all insect species) • Hosts of parasitoids = virtually all terrestrial insects • Parasitoids are among the dominant natural enemies of phytophagous insects (e.g., crop pests) • Offer model systems for understanding community structure, coevolution & evolutionary diversification Distribution/frequency of parasitoids among insect orders Primary groups of parasitoids Diptera (flies) ca. 20% of parasitoids Hymenoptera (wasps) ca. 70% of parasitoids Described Family Primary hosts Diptera parasitoid sp Sciomyzidae 200? Gastropods: (snails/slugs) Nemestrinidae 300 Orth.: Acrididae Bombyliidae 5000 primarily Hym., Col., Dip. Pipunculidae 1000 Hom.:Auchenorrycha Conopidae 800 Hym:Aculeata Lep., Orth., Hom., Col., Sarcophagidae 1250? Gastropoda + others Lep., Hym., Col., Hem., Tachinidae > 8500 Dip., + many others Pyrgotidae 350 Col:Scarabaeidae Acroceridae 500 Arach.:Aranea Hym., Dip., Col., Lep., Phoridae 400?? Isop.,Diplopoda -

Lateinischer Tiernamen. Anonymus

A Index lateinischer Tiernamen Die AutorennameaSubgenus- und Subspeziesbezeichnungen sind dem Textteil zu entnehmen! Abdera 71 Alburnus alburnus 54, 56 Aporia crataegi 102 Abramis brama 53 - bipunctatus 56 Aporophila lutulenta 108 Abraxas grossulariata 111 Alcedo atthis 44 Aquila chrysaetos 44 Acanthocinus griseus 84 Alcis jubata 112 - clanga 46 - reticulatus 84 Alectoris graeca 43 - heliaca 46 Acasis appensata 123 Allophyes oxyacanthae 109 - pomarina 46 - viretata 112 Aiosa aiosa 53 Araschnia levana 104 Accipiter gentilis 44 Alsophila quadripunctaria 112 Archanara geminipuncta 119 - nisus 44 Amata phegea 107 - neurica 108 Acipenser ruthenus 51, 53, 56 Amathes castanea 108 - sparganii 109 - güldenstädti51,53 - collina 110 Arctaphaenops nihilumalbi 77 Acmaeodera degener 86 Ampedus 68 - styriacus 63, 77 Acmaeoderella ftavofasciata 85 Amphibia 49-50 Arctinia caesarea 117 Acmaeops marginata 79 Amphipoea fucosa 109 Ardea cinerea 44 - pratensis 84 Amphipyra livida 109 - purpurea 43, 46 - septentrionis 84 - tetra 109 Ardeola ralloides 46 Acontia luctuosa 109 Anaesthetis testacea 82 Argante herbsti 86 Acrocephalus schoenobaenus 45 Anaitis efformata 111 Argiope bruenichi 16 Acroloxus lacustris 144 Anarta cordigera 110 Argna biplicata 141,145 Actia infantula 131 - myrtilli 108 Aricia artaxerxes 104 - pilipennis 131 Anas crecca 44 Arion alpinus 141 Actinotia hyperici 108 - querquedula 44 - lusitanicus 141 Actitis hypoleucos 44 Anax parthenope 60 - ruf us 141 Adelocera 68 Ancylus fluviatilis 139, 144 Aromia moschata 82 Admontia blanda 131 Anemadus -

The Relationship Between the Winter Moth (Operophtera Brumata) and Its Host Plants in Coastal Maine Kaitlyn M

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library Summer 8-2015 The Relationship Between the Winter Moth (Operophtera brumata) and Its Host Plants in Coastal Maine Kaitlyn M. O'Donnell University of Maine - Main, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Biology Commons, and the Other Forestry and Forest Sciences Commons Recommended Citation O'Donnell, Kaitlyn M., "The Relationship Between the Winter Moth (Operophtera brumata) and Its Host Plants in Coastal Maine" (2015). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2338. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/2338 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE WINTER MOTH (OPEROPTHERA BRUMATA) AND ITS HOST PLANTS IN COASTAL MAINE By Kaitlyn O’Donnell B.S. Saint Michael’s College, 2011 A THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science (in Entomology) The Graduate School The University of Maine August 2015 Advisory Committee: Eleanor Groden, Professor of Entomology, School of Biology and Ecology, Advisor Francis Drummond, Professor of Insect Ecology and Wild Blueberry Pest Management Specialist, School of Biology and Ecology and the University of Maine Cooperative Extension Joseph Elkinton, Professor of Environmental Conservation, University of Massachusetts Charlene Donahue, Forest Entomologist, Maine Forest Service THESIS ACCEPTANCE STATEMENT On behalf of the Graduate Committee for Kaitlyn O’Donnell I affirm that this manuscript is the final and accepted thesis. -

2017 Winter Moth Caterpillar Update

T O W N O F W E L L E S L E Y M A S S A C H U S E T T S DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS PARK & TREE DIVISION 30 MUNICIPAL WAY WELLESLEY, MA 02481-4925 MICHAEL T. QUINN TELEPHONE (781) 235-7600 ASSISTANT SUPERINTENDENT EXT. 3331 DEPUTY TREE WARDEN FACSIMILE (781) 431-7569 WWW. WELLESLEYMA.GOV [email protected] 2017 Winter Moth Caterpillar Update In Wellesley and throughout eastern Massachusetts the winter moth caterpillar has been defoliating trees during the spring. Under the authority of the Natural Resources Commission and the guidelines of the Wellesley Integrated Pest Management Policy, the Department of Public Works will be deferring the ground spraying town trees to control winter moth caterpillars, unless an identified tree is determined in need of spraying in order to survive. These exceptions will be treated with Conserve #SC, a spinosad based product, E.P.A. Reg. #62719-291. Hours of spraying will occur between 5am thru 10 am. and will not occur after May 30th, 2016. All treated areas will be posted for 24 hours before and after applications. This is the same strategy we applied in 2014, 2015 AND 2016. During those years we found no trees in need of spraying. The reason for this strategy is due to a team of scientists led by Joseph Elkinton at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. This team released approximately 1,000 parasitic flies at Centennial Park in Wellesley on May 9th, 2008, to help biologically control this invasive caterpillar. In eastern Massachusetts this caterpillar has been stripping the foliage from many kinds of deciduous trees in towns that stretch from the North Shore to Cape Cod. -

Winter Moth After Hatching, the Young Larvae Crawl up Tree Trunks and Produce Silken Threads That Can Carry Operophtera Brumata Them in the Wind

Department of Conservation and Recreation pest P.O. Box 484, Amherst, MA 01004 Tel: 413-256-1601 alert www.mass.gov/dcr Winter Moth After hatching, the young larvae crawl up tree trunks and produce silken threads that can carry Operophtera brumata them in the wind. This dispersal method, called The winter moth was introduced to North America “ballooning,” is common among defoliators. Larvae from Europe and was first recorded in Nova Scotia are light green loopers (inchworms) that measure in the early 1930s. Infestations are now known to about one inch in length when fully grown. Young occur in New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, larvae feed within buds and on expanding foliage, British Columbia, Washington, and Oregon, and while older larvae can consume entire leaves. the pest is now established in coastal Massachusetts Feeding is generally completed by mid-June when from Orleans on Cape Cod to Gloucester on larvae pupate in the soil. Cape Ann. There are also unconfirmed reports of spotty infestations along Route 495 south of the Control Massachusetts Turnpike. No natural controls are known to be present in Massachusetts, but researchers at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst are actively collecting and rearing a parasitic fly Cyzenis( albicans) that was very effective at controlling winter moth outbreaks in eastern Canada and the Pacific Northwest. Unfortunately, effective biological control is many years away. For recently defoliated trees, an application of a registered pesticide may be warranted. For more information on currently registered Female and male winter moth (USDA Forest Service photo) pesticides, please contact your local extension service office or visit the cooperative extension Winter Moths in Massachusetts website at: www.umassgreeninfo.org/fact_sheets. -

The Phylogenetics of Tachinidae (Insecta: Diptera) with an Emphasis on Subfamily Structure

Wright State University CORE Scholar Browse all Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2013 The Phylogenetics of Tachinidae (insecta: Diptera) with an Emphasis on Subfamily Structure Daniel J. Davis Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all Part of the Biology Commons Repository Citation Davis, Daniel J., "The Phylogenetics of Tachinidae (insecta: Diptera) with an Emphasis on Subfamily Structure" (2013). Browse all Theses and Dissertations. 650. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all/650 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Browse all Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PHYLOGENETIC RELATIONSHIPS OF TACHINIDAE (INSECTA: DIPTERA) WITH A FOCUS ON SUBFAMILY STRUCTURE A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science By DANIEL J DAVIS B.S., Wright State University, 2010 2012 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL December 13, 2012 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Daniel J Davis ENTITLED The phylogenetic relationships of Tachinidae (Insecta: Diptera) with a focus on subfamily structure BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Science _____________________________ John O. Stireman III, Ph.D. Thesis Director _____________________________ David Goldstein, Ph.D., Chair Department of Biological Sciences College of Science and Mathematics Committee on Final Examination ____________________________ John O. Stireman III, Ph.D. ____________________________ Jeffrey L. Peters, Ph.D. -

Proceedings of the 5Th International Symposium on Biological Control of Arthropods (Eds

112 7.1 Friend or Foe: The Role of Native, Natural Enemies in the Biological Control of Winter Moth H.J. Broadley1, J.S. Elkinton2 and G.H. Boettner3 1Organismic and Evolutionary Biology Graduate Program, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Massachusetts, USA, [email protected], 2Department of Environmental Conservation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Massachusetts, USA, [email protected], 3Department of Environmental Conservation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Massachusetts, USA, [email protected] Natural enemies that cross over from related native species to invasive species mediate invasions in complex ways (Strauss et al., 2012; Dearborn et al., 2016; Faillace et al., 2017). They have the potential to slow down invasions and aid in biological control efforts (Kenis et al., 2008; Vindstad et al., 2013; Dearborn et al., 2016). In the northeastern United States, the European winter moth, Operophtera brumata L. (Lepidoptera: Geometridae) is an invasive, forest pest causing widespread defoliation in rural and urban settings (Elkinton et al., 2014). Following successful biological control of winter moth in Nova Scotia and British Columbia using the tachinid fly, Cyzenis albicans (Fallén) (Diptera: Tachinidae) (Embree 1966; Murdoch et al., 1985; Roland and Embree, 1995), similar efforts are underway in the northeastern United States (Elkinton et al., 2015). While biocontrol shows promising results, success likely depends on additional mortality from native natural enemies. In the northeast U.S., the closest relative to winter moth is Bruce spanworm, O. bruceata (Hulst) (Lepidoptera: Geometridae). The two are congeners and can hybridize (Gwiazdowski et al., 2013; Havill et al., 2017), thus it is likely that natural enemies from Bruce spanworm as well as other generalists could cross over to cause mortality to the winter moth population. -

Annotated Host Catalogue for the Tachinidae (Diptera) of Italy

Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde A, Neue Serie 3: 305–340; Stuttgart, 30.IV.2010. 305 Annotated host catalogue for the Tachinidae (Diptera) of Italy PIERFILIPPO CERRETTI & HANS-PETER TSCHORSNIG Abstract An annotated host catalogue is given for the Tachinidae of Italy. It comprises 180 tachinid species reared from 310 arthropod hosts belonging to seven insect orders and one chilopod order. The paper includes data from litera- ture as well as hitherto unpublished records. K e y w o r d s : Tachinidae, parasitoids, host catalogue, Italy. Zusammenfassung Für die italienischen Tachinidae wird ein kritischer Wirtekatalog gegeben. Er umfasst 180 Tachiniden-Arten und 310 Arthropoden-Wirtsarten aus sieben Insektenordnungen und einer Ordnung der Hundertfüßer. Die Arbeit enthält sowohl Daten aus der Literatur als auch bisher unveröffentlichte Wirtsangaben. Contents 1 Introduction .........................................................................................................................................................305 2 Explanation of the format ....................................................................................................................................306 3 Annotated parasitoid-host list .............................................................................................................................306 4 Host-parasitoid list ..............................................................................................................................................325 5 References ...........................................................................................................................................................330 -

4 Economic Value of Arthropod Biological Control

©CAB International – for Steven Naranjo 4 Economic Value of Arthropod Biological Control STEVEN E. NARANJO1*, GEORGE B. FRISVOLD2 AND PETER C. ELLSWORTH3 1USDA-ARS, Arid-Land Agricultural Research Center, Maricopa, AZ, USA; 2Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA; 3Department of Entomology, University of Arizona, Maricopa Agricultural Center, Maricopa, AZ, USA Integrated pest management (IPM) is the strategic control are very low, successful programmes have integration of multiple control tactics resulting in the resulted in essentially permanent pest control with amelioration of pest damage that takes into consid- very favourable economic outcomes (Cock et al., eration environmental safety, and the reduction of 2015; Naranjo et al., 2015). risk and favourable economic outcomes for growers A second approach – augmentative biological and society at large. For thousands of years, natural control – involves the initial (inoculation) or enemies of pests have been harnessed for crop pro- repeated (inundation) introduction of native or tection (Simmonds et al., 1976). Maximizing this exotic natural enemies to suppress pest populations. source of natural control is a foundational element Augmentative biological control has been widely in IPM for suppressing the growth of incipient pest and successfully deployed in many parts of the populations (Stern et al., 1959). Biological control world. It is perhaps most well known in protected has been defined as the purposeful use of natural agricultural production, particularly in Europe and enemies, such as predators, parasitoids and patho- in developing regions such as China, India and gens, to regulate another organism’s populations to Latin America (van Lenteren et al., 2017). -

COMMUNITY FOREST MANAGEMENT PLAN Town of Greenburgh, New York

October 2020 STANDARD INVENTORY ANALYSIS AND COMMUNITY FOREST MANAGEMENT PLAN Town of Greenburgh, New York Prepared for: Prepared by: Town of Greenburgh Davey Resource Group, Inc. Town Hall 295 S. Water Street, Suite 300 117 Hillside Avenue Kent, Ohio 44240 Greenburgh, New York 10607 800-828-8312 Davey Resource Group, Inc.1May 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................................................ ii Standard Inventory Analysis and Community Forest Management Plan Executive Summary ......... iii Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 Section 1: Structure and Composition of the Public Tree Resource .......................................................... 4 Section 2: Functions and Benefits of the Public Tree Resource ................................................................ 19 Section 3: Recommended Management of the Public Tree Resource ..................................................... 26 Conclusion ....................................................................................................................................................... 41 References ........................................................................................................................................................ 43 TABLES 1. Defect observations recorded during the tree inventory .................................................................... -

View the PDF File of the Tachinid Times, Issue 9

The Tachinid Times ISSUE 9 February 1996 Jim O'Hara, editor Agriculture & Agri-Food Canada, Biological Resources Division Centre for Land & Biological Resources Research C.E.F., Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, K1A 0C6 This is the first issue of this newsletter to be offered variegata) is one of the most common pests of many simultaneously (more or less) as hardcopy and over the kinds of roadside trees of urban areas in southern Japan, Internet. For those of you receiving this newsletter in west of Tokyo. This bagworm is never found in natural hardcopy and who wish to view the Internet version, the forests. In the fall of 1995, one of us (TT) collected Internet address of the Biological Resources Division of many specimens of this bagworm near our University our Centre is: http://res.agr.ca/brd/home.html. The campus in Fukuoka and reared them to get some Tachinid Times can be accessed through the BRD parasitoids. Unexpectedly, many individuals of an Homepage. In the years to come the mailing list for the unknown tachinid soon emerged from the bagworms, for hardcopy version of this newsletter will certainly decline the only known tachinid parasitoid of the bagworm is as Internet access becomes more widespread. Exorista japonica and its percentage parasitism had been The Biological Resources Division is about to known to be very low. Later this tachinid was identified undergo another name change. For those attempting to as Nealsomyia rufella (Bezzi), a microtype Oriental keep track, the group of systematists to which I belong tachinid known as a parasitoid of E. -

Chapter 9 Biodiversity of Diptera

Chapter 9 Biodiversity of Diptera Gregory W. Courtney1, Thomas Pape2, Jeffrey H. Skevington3, and Bradley J. Sinclair4 1 Department of Entomology, 432 Science II, Iowa State University, Ames, Iowa 50011 USA 2 Natural History Museum of Denmark, Zoological Museum, Universitetsparken 15, DK – 2100 Copenhagen Denmark 3 Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Canadian National Collection of Insects, Arachnids and Nematodes, K.W. Neatby Building, 960 Carling Avenue, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0C6 Canada 4 Entomology – Ontario Plant Laboratories, Canadian Food Inspection Agency, K.W. Neatby Building, 960 Carling Avenue, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0C6 Canada Insect Biodiversity: Science and Society, 1st edition. Edited by R. Foottit and P. Adler © 2009 Blackwell Publishing, ISBN 978-1-4051-5142-9 185 he Diptera, commonly called true flies or other organic materials that are liquified or can be two-winged flies, are a familiar group of dissolved or suspended in saliva or regurgitated fluid T insects that includes, among many others, (e.g., Calliphoridae, Micropezidae, and Muscidae). The black flies, fruit flies, horse flies, house flies, midges, adults of some groups are predaceous (e.g., Asilidae, and mosquitoes. The Diptera are among the most Empididae, and some Scathophagidae), whereas those diverse insect orders, with estimates of described of a few Diptera (e.g., Deuterophlebiidae and Oestridae) richness ranging from 120,000 to 150,000 species lack mouthparts completely, do not feed, and live for (Colless and McAlpine 1991, Schumann 1992, Brown onlyabrieftime. 2001, Merritt et al. 2003). Our world tally of more As holometabolous insects that undergo complete than 152,000 described species (Table 9.1) is based metamorphosis, the Diptera have a life cycle that primarily on figures extracted from the ‘BioSystematic includes a series of distinct stages or instars.