Mary Slessor and Gender Roles in Scottish African Missions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018 Conforming to General Convention 2018 1 Preface Christians have since ancient times honored men and women whose lives represent heroic commitment to Christ and who have borne witness to their faith even at the cost of their lives. Such witnesses, by the grace of God, live in every age. The criteria used in the selection of those to be commemorated in the Episcopal Church are set out below and represent a growing consensus among provinces of the Anglican Communion also engaged in enriching their calendars. What we celebrate in the lives of the saints is the presence of Christ expressing itself in and through particular lives lived in the midst of specific historical circumstances. In the saints we are not dealing primarily with absolutes of perfection but human lives, in all their diversity, open to the motions of the Holy Spirit. Many a holy life, when carefully examined, will reveal flaws or the bias of a particular moment in history or ecclesial perspective. It should encourage us to realize that the saints, like us, are first and foremost redeemed sinners in whom the risen Christ’s words to St. Paul come to fulfillment, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” The “lesser feasts” provide opportunities for optional observance. They are not intended to replace the fundamental celebration of Sunday and major Holy Days. As the Standing Liturgical Commission and the General Convention add or delete names from the calendar, successive editions of this volume will be published, each edition bearing in the title the date of the General Convention to which it is a response. -

Congo Inland Missionaries

Published in the interest o f the best in the religious, social, and economic phases o f Mennonite culture AFRICA ISSUE This issue is devoted to Mennonite missions in Africa. It constitutes the first attempt at presenting the total effort of American Mennonite missionary work in the "dark" continent of Africa and the results of this work since the beginning of this century. No one w ill question that such a presentation is tim ely. The Congo Inland Mission, sponsored by a number of Mennonite groups, looks back over fifty years of work in the Congo. These are crucial days in Africa. We need to be better in formed about the continent, our work in Africa and the emerging Christian churches which, as the nations within which they are located, have suddenly become independent. MENNO SIMONS ISSUE The January issue of MENNONITE LIFE was devoted to Menno Simons, after whom the Mennonites are named. The many illus trated articles dealing with Menno and the basic beliefs of the Mennonites are of special significance since we are commemo rating the 400fh anniversary of his death. Copies of the January and April issues are available through Mennonite book dealers and the MENNONITE LIFE office. The following are the rates: SUBSCRIPTION RATES One year, $3.00; Three years, $7.50; Five years, $12.50. Single issues, 75 cents. MENNONITE LIFE North Newton, Kansas COVER: Women participate in work of the church in Africa. Photography: Melvin Loewen. MENNONITE LIFE An Illustrated Quarterly EDITOR Cornelius Krahn ASSISTANT TO THE EDITOR John F. Schmidt ASSOCIATE EDITORS Harold S. -

Mary Slessor's Legacy

MARY SLESSOR’S LEGACY: A MODEL FOR 21ST CENTURY MISSIONARIES By AKPANIKA, EKPENYONG NYONG Ph.D. DEPARTMENT OF RELIGIOUS AND CULTURAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF CALABAR PMB 1115, CALABAR, CROSS RIVER STATE, NIGERIA [email protected] or [email protected] Abstract: The story of Miss Mary Mitchell Slessor is not a story of a clairvoyant legend who existed in an abstract world but a historical reality that worked around the then Old Calabar estuary and died on the 15th of January, 1915 at Ikot Oku Use, near Ikot Obong in the present day Akwa Ibom State and was buried at “Udi Mbakara” (Whiteman’s grave) in Calabar, Cross River State. Mary was one of those early missionaries that went to villages in the then Old Calabar where few missionaries dared to go in order to bring hope and light to the people that were in darkness. Through her evangelistic efforts, schools and hospitals were erected on her initiative, babies and twins saved from death, barbaric rites and customs stopped because of her undaunted love and passion for God and the people. After a centenary of death, one can easily conclude that what immortalizes a person is not what he does for himself but what he does for others. Mary Slessor’s name, work and care for twins can never be forgotten even in another century to come. The tripartite purpose of this paper is to first examine the stepping out of Mary Slessor from her comfort zone to Calabar (her initial struggle), her passion for the people of Old Calabar and her relational method of evangelism that endeared her to the heart of the people. -

James Cropper, John Philip and the Researches in South Africa

JAMES CROPPER, JOHN PHILIP AND THE RESEARCHES IN SOUTH AFRICA ROBERT ROSS IN 1835 James Cropper, a prosperous Quaker merchant living in Liverpool and one of the leading British abolitionists, wrote to Dr John Philip, the Superintendent of the London Missionary Society in South Africa, offering to finance the republication of the latter's book, Researches in South Africa, which had been issued seven years earlier. This offer was turned down. This exchange was recorded by William Miller Macmillan in his first major historical work, The Cape Coloured Question,1 which was prirnarily concerned with the struggles of Dr John Philip on behalf of the so-called 'Cape Coloureds'. These resulted in Ordinance 50 of 1828 and its confirmation in London, which lifted any civil disabilities for free people of colour. The correspondence on which it was based, in John Philip's private papers, was destroyed in the 1931 fire in the Gubbins library, Johannesburg, and I have not been able to locate any copies at Cropper's end. Any explanation as to why these letters were written must therefore remain speculative. Nevertheless, even were the correspondence extant, it is unlikely that it would contain a satisfactory explanation of what at first sight might seem a rather curious exchange. The two men had enough in common with each other, and knew each other's minds well enough, for them merely to give their surface motivation, and not to be concerned with deeper ideological justification. And the former level can be reconstructed fairly easily. Cropper, it may be assumed, saw South Africa as a 'warning for the West Indies', which was especially timely in 1835 as the British Caribbean was having to adjust to the emancipation of its slaves.2 The Researches gave many examples of how the nominally free could still be maintained in effective servitude, and Cropper undoubtedly hoped that this pattern would not be repeated. -

The Other Side of the Story: Attempts by Missionaries to Facilitate Landownership by Africans During the Colonial Era

Article The Other Side of the Story: Attempts by Missionaries to Facilitate Landownership by Africans during the Colonial Era R. Simangaliso Kumalo https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2098-3281 University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa [email protected] Abstract This article provides a critique of the role played by progressive missionaries in securing land for the African people in some selected mission stations in South Africa. It argues that, in spite of the dominant narrative that the missionaries played a role in the dispossession of the African people of their land, there are those who refused to participate in the dispossession. Instead, they used their status, colour and privilege to subvert the policy of land dispossession. It critically examines the work done by four progressive missionaries from different denominations in their attempt to subvert the laws of land dispossession by facilitating land ownership for Africans. The article interacts with the work of Revs John Philip (LMS), James Allison (Methodist), William Wilcox and John Langalibalele Dube (American Zulu Mission [AZM]), who devised land redistributive mechanisms as part of their mission strategies to benefit the disenfranchised Africans. Keywords: London Missionary Society; land dispossession; Khoisan; mission stations; Congregational Church; Inanda; Edendale; Indaleni; Mahamba Studia Historiae Ecclesiasticae https://doi.org/10.25159/2412-4265/6800 https://upjournals.co.za/index.php/SHE/index ISSN 2412-4265 (Online) ISSN 1017-0499 (Print) Volume 46 | Number 2 | 2020 | #6800 | 17 pages © The Author(s) 2020 Published by the Church History Society of Southern Africa and Unisa Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/) Kumalo Introduction In our African culture, we are integrally connected to the land from the time of our birth. -

Thesis Hum 2007 Mcdonald J.Pdf

The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town 'When Shall These Dry Bones Live?' Interactions between the London Missionary Society and the San Along the Cape's North-Eastern Frontier, 1790-1833. Jared McDonald MCDJAR001 A dissertation submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Arts in Historical Studies Faculty of the Humanities University of Cape Town 2007 University of Cape Town COMPULSORY DECLARATION This work has not been previously submitted in whole, or in part, for the award of any degree. It is my own work. Each significant contribution to, and quotation in, this dissertation from the work, or works, of other people has been attributed, and has been cited and referenced. Signature:_fu""""',_..,"<_l_'"'"-_(......\b __ ~_L ___ _ Date: 7 September 2007 "And the Lord said to me, Prophe,\y to these bones, and scry to them, o dry bones. hear the Word ofthe Lord!" Ezekiel 37:4 Town "The Bushmen have remained in greater numbers at this station ... They attend regularly to hear the Word of God but as yet none have experiencedCape the saving effects ofthe Gospe/. When shall these dry bones oflive? Lord thou knowest. -

Copyright © and Moral Rights for This Thesis Are Retained by the Author And/Or Other Copyright Owners

McDonald, Jared. (2015) Subjects of the Crown: Khoesan identity and assimilation in the Cape Colony, c. 1795- 1858. PhD thesis. SOAS University of London. http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/22831/ Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Subjects of the Crown: Khoesan Identity and Assimilation in the Cape Colony, c.1795-1858 Jared McDonald Department of History School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) University of London A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in History 2015 Declaration for PhD Thesis I declare that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the thesis which I present for examination. -

Prayer Manual Like Wells

“On the 125th anniversary of the departure of the Cambridge Seven MISSION for China, this is a devotional prayer guide for a season of prayer for a youth awakening leading to a missions movement.” HerOES The spiritual fathers of the Christian faith are PRAYER MANUAL like wells. As we have failed to draw from their inspiration and example, those wells have become blocked. This guide is designed to reminds us of the mission heroes of this nation, and to help us call upon the Lord to open those wells again. Andrew Taylor has worked with Youth With A Mission for 27 years. For some years he was responsible for YWAM’s Operation Year programme, discipling youth and training leaders. Recently he has been studying leadership and researching discipleship.” Published by Registered Charity No. 264078 M THE ANCIENT WELLS DRAWING INS PIRATION FRO 2010-46 Mission Heroes Cover.ind1 1 23/7/10 10:48:32 MISSION HerOES PRAYER MANUAL DRAWING INSPIRATION FROM THE ANCIENT WELLS Celebrating the 125th anniversary of the departure for China of the Cambridge Seven in 1885 Andrew J. Taylor ‘He will restore the hearts of the fathers to their children’ Malachi 4:6 (NASB) This edition first published in Great Britain by YWAM Publishing Ltd, 2010 Copyright © 2010 YWAM Publishing The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. -

C.S. Lewis's Humble and Thoughtful Gift of Letter Writing

KNOWING . OING &DC S L EWI S I N S TITUTE Fall 2013 A Teaching Quarterly for Discipleship of Heart and Mind C.S. Lewis’s Humble and Thoughtful Gift of Letter Writing by Joel S. Woodruff, Ed.D. Vice President of Discipleship and Outreach, C.S. Lewis Institute s it a sin to love Aslan, the lion of Narnia, Recalling your tears, I long to see you, so that more than Jesus? This was the concern ex- I may be filled with joy” (2 Tim. 1:2–4 NIV). Ipressed by a nine-year-old American to his The letters of Paul, Peter, John, James, and Jude mother after reading The Chronicles of Narnia. that fill our New Testament give witness to the IN THIS ISSUE How does a mother respond to a question like power of letters to be used by God to disciple that? In this case, she turned straight to the au- and nourish followers of Jesus. While the let- 2 Notes from thor of Narnia, C.S. Lewis, by writing him a let- ters of C.S. Lewis certainly cannot be compared the President ter. At the time, Lewis was receiving hundreds in inspiration and authority to the canon of the by Kerry Knott of letters every year from fans. Surely a busy Holy Scriptures, it is clear that letter writing is scholar, writer, and Christian apologist of inter- a gift and ministry that when developed and 3 Ambassadors at national fame wouldn’t have the time to deal shared with others can still influence lives for the Office by Jeff with this query from a child. -

Juvenile Missionary Biographies, C. 1870-1917 'Thesis Submitted in Accordance with the Requirem

Imagining the Missionary Hero: Juvenile Missionary Biographies, c. 1870-1917 ‘Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy by Julie Anne McColl.’ December 2017 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the fascinating and complex body of work surrounding the missionary hero as a product of late imperial ideas of the heroic produced in the form of biography. It will concentrate upon how the literature was appropriated, reproduced and disseminated via the Sunday school network to working-class children between 1870 and 1917. It will discuss how biographers through imaginative narrative strategies and the reframing of the biography as an adventure story, were able to offer children a physical exemplar and self-sacrificial hero who dispensed clear imperial ideas and moral values. This thesis will reflect upon how the narratives embedded in dominant discourses provided working-class children with imperial ideologies including ideas of citizenship and self-help which it will argue allowed groups of Sunday school readers to feel part of an imagined community. In doing so, the thesis sheds important new light on a central point of contention in the considerable and often heated discussion that has developed since the 1980s around the impact of empire on British people.Through an analysis of common themes it will also consider the depiction of women missionaries, asking whether biographical representation challenged or reinforced traditional gender ideologies. To interrogate these components effectively this thesis is divided into two parts, Part One is divided into five chapters providing context, while Part Two will look in detail at the repetition and adaption of common themes. -

Philip De La Mare, Pioneer Industrialist

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1959 Philip De La Mare, Pioneer Industrialist Leon R. Hartshorn Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Hartshorn, Leon R., "Philip De La Mare, Pioneer Industrialist" (1959). Theses and Dissertations. 4770. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4770 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. To my father whose interest, love, kindness and generosity have made not only this endeavor but many others possible. PHILIP DE LA MARE PIONEER INDUSTRIALIST A Thesis Submitted to The College of Religious Instruction Brigham Young University Provo, Utah In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science by Leon R. Hartshorn July 1959 ACKNOWLEDGMENT Seldom, if ever, do we accomplish anything alone. The confidence and support of family, friends and interested individuals have made an idea a reality* I express my most sincere thanks to my devoted wife, who has taken countless hours from her duties as a homemaker and mother to assist and encourage me in this endeavor, I am grateful to my advisors: Dr. Russell R. Rich for his detailed evaluation of this writing and for his friendliness and kindly interest and to Dr. B. West Belnap for his help and encouragement. My thanks to President Alex F. -

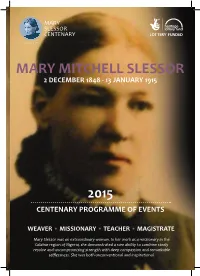

Centenary Programme of Events

MARY SLESSOR CENTENARY 1848-1915 2 DECEMBER 1848 - 13 JANUARY 1915 CENTENARY PROGRAMME OF EVENTS Mary Slessor was an extraordinary woman. In her work as a missionary in the Calabar region of Nigeria, she demonstrated a rare ability to combine steely resolve and uncompromising strength with deep compassion and remarkable selflessness. She was both unconventional and inspirational. Design by Dundee City Council, Communications Division CONTENTS Welcome 3 Mary Slessor 4 Dundee in 1876 5 The Mary Slessor Foundation 6 Centenary Events 8 Commemorative Standing Stone Location 10 Selection 11 Preparation and Transportation 11 Excavation and Installation 12 Commemorative Plaques Making of the Plaques 13 Brief, Portrait, Pattern Making 13 Text Plaque Pattern, Sand Mould, Casting 14 Chasing, Patination 15 Installation 16 Stained Glass Memorial Window 17 Mother of All the Peoples 18 Mary Slessor Centenary Exhibition 19 Competitions 20 Thank You to Our Supporters 21 More Thanks 23 At the time of going to print all of the information in this publication was correct. Mary Slessor Foundation are not responsible for any changes made to any of the events that are outwith their control. 2 2015 marks the centenary of the death of Mary Slessor. The Mary Slessor Foundation in conjunction with a number of individuals, companies and organisations has arranged a series of events to commemorate this. Mary Slessor’s story is virtually unknown locally or nationally and one of our objectives in this centenary year is to change that. This initiative is intend- ed to raise her profile and also increase awareness of the work that the Foundation carries out in her name in a part of Africa in which she lived and worked, but also loved.