Mary Slessor's Legacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018 Conforming to General Convention 2018 1 Preface Christians have since ancient times honored men and women whose lives represent heroic commitment to Christ and who have borne witness to their faith even at the cost of their lives. Such witnesses, by the grace of God, live in every age. The criteria used in the selection of those to be commemorated in the Episcopal Church are set out below and represent a growing consensus among provinces of the Anglican Communion also engaged in enriching their calendars. What we celebrate in the lives of the saints is the presence of Christ expressing itself in and through particular lives lived in the midst of specific historical circumstances. In the saints we are not dealing primarily with absolutes of perfection but human lives, in all their diversity, open to the motions of the Holy Spirit. Many a holy life, when carefully examined, will reveal flaws or the bias of a particular moment in history or ecclesial perspective. It should encourage us to realize that the saints, like us, are first and foremost redeemed sinners in whom the risen Christ’s words to St. Paul come to fulfillment, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” The “lesser feasts” provide opportunities for optional observance. They are not intended to replace the fundamental celebration of Sunday and major Holy Days. As the Standing Liturgical Commission and the General Convention add or delete names from the calendar, successive editions of this volume will be published, each edition bearing in the title the date of the General Convention to which it is a response. -

Congo Inland Missionaries

Published in the interest o f the best in the religious, social, and economic phases o f Mennonite culture AFRICA ISSUE This issue is devoted to Mennonite missions in Africa. It constitutes the first attempt at presenting the total effort of American Mennonite missionary work in the "dark" continent of Africa and the results of this work since the beginning of this century. No one w ill question that such a presentation is tim ely. The Congo Inland Mission, sponsored by a number of Mennonite groups, looks back over fifty years of work in the Congo. These are crucial days in Africa. We need to be better in formed about the continent, our work in Africa and the emerging Christian churches which, as the nations within which they are located, have suddenly become independent. MENNO SIMONS ISSUE The January issue of MENNONITE LIFE was devoted to Menno Simons, after whom the Mennonites are named. The many illus trated articles dealing with Menno and the basic beliefs of the Mennonites are of special significance since we are commemo rating the 400fh anniversary of his death. Copies of the January and April issues are available through Mennonite book dealers and the MENNONITE LIFE office. The following are the rates: SUBSCRIPTION RATES One year, $3.00; Three years, $7.50; Five years, $12.50. Single issues, 75 cents. MENNONITE LIFE North Newton, Kansas COVER: Women participate in work of the church in Africa. Photography: Melvin Loewen. MENNONITE LIFE An Illustrated Quarterly EDITOR Cornelius Krahn ASSISTANT TO THE EDITOR John F. Schmidt ASSOCIATE EDITORS Harold S. -

Prayer Manual Like Wells

“On the 125th anniversary of the departure of the Cambridge Seven MISSION for China, this is a devotional prayer guide for a season of prayer for a youth awakening leading to a missions movement.” HerOES The spiritual fathers of the Christian faith are PRAYER MANUAL like wells. As we have failed to draw from their inspiration and example, those wells have become blocked. This guide is designed to reminds us of the mission heroes of this nation, and to help us call upon the Lord to open those wells again. Andrew Taylor has worked with Youth With A Mission for 27 years. For some years he was responsible for YWAM’s Operation Year programme, discipling youth and training leaders. Recently he has been studying leadership and researching discipleship.” Published by Registered Charity No. 264078 M THE ANCIENT WELLS DRAWING INS PIRATION FRO 2010-46 Mission Heroes Cover.ind1 1 23/7/10 10:48:32 MISSION HerOES PRAYER MANUAL DRAWING INSPIRATION FROM THE ANCIENT WELLS Celebrating the 125th anniversary of the departure for China of the Cambridge Seven in 1885 Andrew J. Taylor ‘He will restore the hearts of the fathers to their children’ Malachi 4:6 (NASB) This edition first published in Great Britain by YWAM Publishing Ltd, 2010 Copyright © 2010 YWAM Publishing The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. -

Juvenile Missionary Biographies, C. 1870-1917 'Thesis Submitted in Accordance with the Requirem

Imagining the Missionary Hero: Juvenile Missionary Biographies, c. 1870-1917 ‘Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy by Julie Anne McColl.’ December 2017 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the fascinating and complex body of work surrounding the missionary hero as a product of late imperial ideas of the heroic produced in the form of biography. It will concentrate upon how the literature was appropriated, reproduced and disseminated via the Sunday school network to working-class children between 1870 and 1917. It will discuss how biographers through imaginative narrative strategies and the reframing of the biography as an adventure story, were able to offer children a physical exemplar and self-sacrificial hero who dispensed clear imperial ideas and moral values. This thesis will reflect upon how the narratives embedded in dominant discourses provided working-class children with imperial ideologies including ideas of citizenship and self-help which it will argue allowed groups of Sunday school readers to feel part of an imagined community. In doing so, the thesis sheds important new light on a central point of contention in the considerable and often heated discussion that has developed since the 1980s around the impact of empire on British people.Through an analysis of common themes it will also consider the depiction of women missionaries, asking whether biographical representation challenged or reinforced traditional gender ideologies. To interrogate these components effectively this thesis is divided into two parts, Part One is divided into five chapters providing context, while Part Two will look in detail at the repetition and adaption of common themes. -

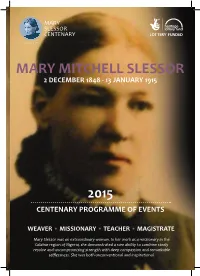

Centenary Programme of Events

MARY SLESSOR CENTENARY 1848-1915 2 DECEMBER 1848 - 13 JANUARY 1915 CENTENARY PROGRAMME OF EVENTS Mary Slessor was an extraordinary woman. In her work as a missionary in the Calabar region of Nigeria, she demonstrated a rare ability to combine steely resolve and uncompromising strength with deep compassion and remarkable selflessness. She was both unconventional and inspirational. Design by Dundee City Council, Communications Division CONTENTS Welcome 3 Mary Slessor 4 Dundee in 1876 5 The Mary Slessor Foundation 6 Centenary Events 8 Commemorative Standing Stone Location 10 Selection 11 Preparation and Transportation 11 Excavation and Installation 12 Commemorative Plaques Making of the Plaques 13 Brief, Portrait, Pattern Making 13 Text Plaque Pattern, Sand Mould, Casting 14 Chasing, Patination 15 Installation 16 Stained Glass Memorial Window 17 Mother of All the Peoples 18 Mary Slessor Centenary Exhibition 19 Competitions 20 Thank You to Our Supporters 21 More Thanks 23 At the time of going to print all of the information in this publication was correct. Mary Slessor Foundation are not responsible for any changes made to any of the events that are outwith their control. 2 2015 marks the centenary of the death of Mary Slessor. The Mary Slessor Foundation in conjunction with a number of individuals, companies and organisations has arranged a series of events to commemorate this. Mary Slessor’s story is virtually unknown locally or nationally and one of our objectives in this centenary year is to change that. This initiative is intend- ed to raise her profile and also increase awareness of the work that the Foundation carries out in her name in a part of Africa in which she lived and worked, but also loved. -

Knowing Doing

Knowing oing &D. C S L e w i S i n S t i t u t e Profile in faith Mary Slessor “Mother of All the Peoples” by David B. Calhoun Professor Emeritus, Covenant Theological Seminary in St. Louis, Missouri This article originally appeared in the Winter 2010 issue of Knowing & Doing. aking a purchase a few years ago in a book- and sailed on the SS Ethiopia in 1876. When she saw store in St. Andrews, Scotland, I was given a scores of casks of rum being loaded onto the ship, Mten-pound note as part of my change. I was Mary ruefully exclaimed, “All that rum! And only amazed and pleased to see the face of Mary Slessor on one missionary!” the front and a map of her mission station in Calabar, With Mary Slessor, the mission in Calabar had a now eastern Nigeria, on the back of the note. staff of thirteen. Some of the missionaries were Scot- Mary Slessor was born into a poor family in Aber- tish; some were Jamaican. The mission had been deen, Scotland in December 1848, the second of seven founded in 1824 by Hope Masterton Waddell, an Irish 1 children. Mary’s father, a shoemaker, was an alcohol- clergyman who had served in Jamaica. He became ic. Seeking a new beginning, he moved the family to convinced that Black Christians from the West Indies Dundee, where they lived in a tiny one-room house, could and should go to Africa as missionaries. with no water and of course no electricity. -

Lecture 28 – “The Last Command”: Missions in “The Great Century”

Reformation & Modern Church History Lecture 28, page 1 Lecture 28 – “The Last Command”: Missions in “the Great Century” “Therefore go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you.” Matthew 28: 19, 20 Background Reading Gonzalez, ch. 30 Prayer From Betty Stam “I give up all my own plans and purposes, all my own desires and hopes, and accept Thy will for my life. I give myself, my life, my all utterly to Thee to be thine forever. Fill me with Thy Holy Spirit, use me as Thou will, send me where Thou will, work out Thy whole will in my life at any cost. Now and forever. Amen.” “The Last Command”: Missions in “the Great Century” I. Catholic Missions II. Early Protestant Efforts A. Home missions B. The Huguenot mission to Brazil C. The Dutch Calvinists 1. “Church planting” 2. Missiological writings of Gisbertus Voetius D. The English and New England Puritans Seal of the Massachusetts Bay Company pictured an Indian and the words, “Come over and help us”; Charter charged the company officials to win the natives to “the only true God and Savior of mankind.” 1. John Eliot (1604-90) “Prayer and pains, through faith in Jesus Christ, will do anything.” 2. Thomas Mayhew (1620-57) 3. David Brainerd (1718-47) Diary, Thursday, May 22, 1746: “If ever my soul presented itself to God for His service, without any reserve, it did so now. -

MS518 Missions Sheppard Sp

MISSIONS - MS 518 Spring Term 2018 (March 18-21, 2019) Reformed Theological Seminary/Charlotte Dr. Craig Sheppard Course Description This course presents and examines world missions from three perspectives: the Biblical theology of missions; the history of missions; and current trends, methods, and issues facing missions. Course goals 1. To enable the student to articulate a Biblical theology of missions and evaluate missiological trends and practices in light of it. 2. To enable the student to better understand the biblical/theological mandate of world evangelization, discipleship and church planting. 3. To enable the student to understand the role of the local pastor in leading his congregation in obedience to the Great Commission. 4. To introduce the student to the history and the leading personalities of Christian missions. 5. To prepare the student to interact Biblically with the various challenges, debates and opportunities facing the church today in light of globalization, economics, politics, and technology. 6. To equip the student to develop and implement a church-based strategy for world missions that will bear fruit both in the greater worldwide missions task and in the hearts of individual believers, resulting in missions-minded and missions-active congregations. 7. To acquaint the student with the various resources and agencies available for continued growth and participation in world missions. Course Assignments 1. Read Ruth Tucker’s From Jerusalem to Irian Jaya, chapters 1-8 and 10-15 (approximately 360pp). (Because this is an one-week intensive course, it is highly recommended that this book be read before the beginning of the course) 2. -

Blackburn Prayers January 2020

Blackburn Prayers January 2020 In 2020 we are continuing to share Bishop Julian’s three Bible verses to meditate on and memorise each month as part of his 'Bishop's Bible Challenge' and to encourage the spiritual discipline of learning Bible verses by heart. There is more information from Bishop Julian about the Bible Challenge on the Diocesan website here. We are continuing with Vision 2026 prayers that reflect the themes of Making Disciples, Being Witnesses, Growing Leaders and Youth/Children and Schools. For 2020, we have also included prayers for our National Church Funded Projects in Blackpool, Blackburn and Preston. As always, if you have an event coming up in your parish for which you would particularly value prayer, please let us know by January 10 for the February edition. Any comments, amendments or updates regarding Blackburn Prayers should be directed to [email protected]. If you want to find out more about any of the parishes in this month’s edition, click on the name of the parish and it will take you to either their own website or to their page on the A Church Near You site. Key: cw = churchwarden of vacant parish Wednesday 1 January Bishop’s Memory Verse: Making Disciples – Mark 8.34 Naming and Circumcision of Jesus called the crowd with his disciples, and said to them, “If any want Jesus to become my followers, let them deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me”. For Derek and Nerina Harborne working with African Inland Mission (AIM) in Mbarara, Uganda. -

Or Mary Slessor of Dundee Armies and Demanding They Pile Their Weapons (Where She Lived and Worked) but Mary Slessor at Her Feet

er name was Mary Slessor of Calabar. weapons to her. Once she halted an intertribal HNot Mary Slessor of Aberdeen (where war by marching between the two opposing she was born) or Mary Slessor of Dundee armies and demanding they pile their weapons (where she lived and worked) but Mary Slessor at her feet. The heap of spears, bows, arrows, of Calabar. She would be given many titles and clubs, and knives that was laid at her feet was nicknames: “The White Queen,” “The White Ma five-feet high! The protection of the Lord Who who lives alone,” and “The Ma who loves sent her and the respect she had among the babies.” To British administrators she was “the tribes were all that preserved her life. uncrowned queen whose word was law,” because of her influence over otherwise She labored for 39 years in Calabar (in what is uncontrollable natives. But her enduring title modern-day Nigeria). The impact this little links her name inseparably with the land where woman had was completely out of proportion she labored for the Lord she loved: to her size. She brought the Gospel to souls who “Mary Slessor of Calabar.” otherwise would never have heard it. A hymn she taught the natives sums up her message: Born on December 2, 1848, Mary was converted as a child in Dundee, Scotland, where Jesus the Son of God came down to earth; her father was an abusive drunk and her He came to save us from our sins. mother a factory worker. When she was 11 He was born poor that He might feel for us. -

Chapter Two, October 2018

Chapter Two, October 2018 Fountain House, 3 Conduit Mews, London SE18 7AP, England E-Mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 208 316 5389 No. Author Title Publisher StatBind. Price History 1 A., D. B. E. Separation Words of Truth S pb 0.50 2 Anderson, James They finished Their Course in the Eighties J. Ritchie S pb 4.00 3 Anderson, John A. Heralds of the Dawn James M. Ritchie S pb 3.00 4 Arnot, F. S. Garenganze: West and East Walter G. Wheeler S hb 8.00 5 Arnott, Anne The Brethren A. R. Mowbray S hb 4.00 6 Arnott, Anne The Brethren Mowbray S pb 3.00 7 B., C. The Reading Question: A History & Review Bible Truth Depot S pb 8.00 8 Bamford, Alan Where do we go From Here? H. E. Walter S pb 2.00 9 Barnado-Barnado Memoirs of the Late Dr Barnado Hodder & Stoughton S hb 15.00 10 Barton, D. A. Discovering Chapels and Meeting Houses Shire Publications S pb 3.00 11 Beattie, David J. Brethren, The Story of a Great Recovery J. Ritchie S hb 18.00 12 Bellett-His Daughter Recollections of the Late J. G. Bellett A. S. Rouse S hb 12.00 13 Brady&Evans Christian Brethren in Manchester & District: A History Heritage Publications new pb 8.00 14 Brainerd-Edwards The Life & Diary of David Brainerd Moody Press S hb 6.00 15 Brainerd-Page David Brainerd, The Apostle of the North American Indians J. Ritchie S hb 3.00 16 Brainerd-Smith David Brainerd, His Message For Today Marshall, Morgan & Scott S hb 3.00 17 Broadbent, E. -

Mary Slessor “Mother of All the Peoples” by David B

Knowing . oing &DC S L e w i S i n S t i t u t e Winter 2010 A Teaching Quarterly for Discipleship of Heart and Mind Profile in faith Mary Slessor “Mother of All the Peoples” by David B. Calhoun Professor Emeritus, Covenant Theological Seminary, St. Louis, Missouri IN This Issue aking a purchase a few years ago the poor as one of themselves . She in a bookstore in St. Andrews, stooped very low. She became an angel of 2 Notes from Scotland, I was given a ten-pound mercy in miserable homes.” the President M by Kerry Knott note as part of my change. I was amazed Like her hero, David Livingstone, Mary 3 Holy Conference: and pleased to see the face of Mary Slessor read and studied books while she worked “A Kinde of on the front and a map of her mission sta- at her loom. More and more she was drawn Paradise” tion in Calabar, now eastern Nigeria, on the to missionary work—by her mother’s influ- by Joanne Jung back of the note. ence, the stories of the mission work of her 4 Self-Deception Mary Slessor was born into a poor fami- United Presbyterian Church reported in the and Christian Life ly in Aberdeen, Scotland in December 1848, Missionary Record, and the death of David by Gregg Ten Elshof 1 the second of seven children. Mary’s fa- Livingstone in 1874. 6 The Credibility of ther, a shoemaker, was an alcoholic. Seek- the Christian Life in To the delight of her mother, Mary volun- the Contemporary ing a new beginning, he moved the family teered as a missionary to Calabar, Nigeria.