Interview of Deborah Estrin Was Initially Master’S Students, Depending on the Mix of Conducted by David Walden on 19 Nov

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ucla Computer Science Depart "Tment

THE UCLA COMPUTER SCIENCE DEPART"TMENT QUARTERLY THE DEPARTMENT AND ITS PEOPLE FALL 1987/WINTER 1988 VOL. 16 NO. 1 SCHOOL OF ENGINEERING AND APPLIED SCIENCE COMPUTER SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OFFICERS Dr. Gerald Estrin, Chair Dr. Jack W. Carlyle, Vice Chair, Planning & Resources Dr. Sheila Greibach, Vice Chair, Graduate Affairs Dr. Lawrence McNamee, Vice Chair, Undergraduate Affairs Mrs. Arlene C. Weber, Management Services Officer Room 3713 Boelter Hall QUARTERLY STAFF Dr. Sheila Greibach, Editor Ms. Marta Cervantes, Coordinator Material in this publication may not be reproduced without written permission of the Computer Science Department. Subscriptions to this publication are available at $20.00/year (three issues) by contacting Ms. Brenda Ramsey, UCLA Computer Science Department, 3713 Boelter Hall, Los Angeles, CA 90024-1596. THE UCLA COMPUTER SCIENCE DEPARTMENT QUARTERLY The Computer Science Department And Its People Fall Quarter 1987/Winter Quarter 1988 Vol. 16, No. 1 SCHOOL OF ENGINEERING AND APPLIED SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, LOS ANGELES Fall-Winfer CSD Quarterly CONTENTS COMPUTER SCIENCE AT UCLA AND COMPUTER SCIENCE IN THE UNITED STATES GeraldEstrin, Chair...................................................................................................... I THE UNIVERSITY CONTEXT .............................................................................................. 13 THE UCLA COMPUTER SCIENCE DEPARTMENT The Faculty A rane nf;ntraract Biographies ............................................................................................................................. -

JULY 14-15, 1980 SNOWBIRD, UTAH Princeton, NJ 08544 Charlottesville

MEETING OF CHAIRMEN OF PH.D. GRANTING DEPARTMENTS OF COMPUTER SCIENCE mJ JULY 14-15, 1980 SNOWBIRD, UTAH ATTENDANCE LIST Professor Donald Allison Professor Lee W. Cooprider Dept. of Computer Science Dept. of Computer Science Virginia Polytechnic Inst. Univ. of So. California and State University Los Angeles, CA 90007 Blacksburg, VA 24061 Profesor Saul Amarel Professor Jerome R. Cox, Jr. Dept. of Computer Science Dept. of Computer Science Rutgers University Washington University New Brunswick, NJ 08903 St. Louis, MO 63130 Professor Bruce W. Arden Professor Peter Denning EECS Dept., Eng. Quad. Dept. of Computer Science Princeton University Purdue University Princeton, NJ 08544 West Lafayette, IN 47907 Mr. Bruce Barnes Professor David P. Dobkin Div. Math. & CS. Dept. of Computer Science National Science Foundation The University of Arizona Washington, D.C. 20550 Tucson, AZ 85721 Professor Alan Batson Dr. George G. Dodd DAMACS, Thornton Hall Dept. of Computer University Science of Virginia General Motors Research Lab. Charlottesville, VA 22901 Warren, MI 48090 Professor John Brzozowski Dr. Richard Eckhouse, Jr. Dept. of Computer Science External Research Program University of Waterloo D.E.C.-ML 3/T4l Waterloo, Ontario 146 Main Street Canada N2L 3GI Maynard, MA 01754 Professor William G. Bulgren Professor Gerald Estrin Dept. of Computer Science Dept. of Computer Science University of Kansas 373 Boelter Hall Lawrence, KS 66045 Univ. of CA., Los Angeles Los Angeles, CA 90024 Professor B. F. Caviness Dr. Thelma Estrin Dept. of Math. Science Dept. of Computer Science R.P.I. Univ. of CA., Los Angeles Troy, NY 12181 Los Angeles, CA 90024 Professor S. -

The UCLA Fixed-Plus-Variable (F+V) Structure Computer

Reconfigurable Computer Origins: The UCLA Fixed-Plus-Variable (F+V) Structure Computer Gerald Estrin University of California at Los Angeles Gerald Estrin and his group at the University of California at Los Angeles did the earliest work on reconfigurable computer architectures. The early research, described here, provides pointers to work on models and tools for reconfigurable systems design and analysis. The earliest work on reconfigurable computer Pasta’s challenge architecture was done at the University of What triggered the UCLA work on reconfig- California at Los Angeles (UCLA), as a 1999 urable computer systems? In the spring of report in The Economist noted (see “The 1959, John Pasta, a highly respected applied Economist: Reconfigurable Systems Undergo mathematician and physicist and chairman of Revival” sidebar, p. 4). Clearly, in retrospect, the Mathematics and Computer Science digital technology was not ready for such a rev- Research Advisory Committee to the Atomic olutionary change. Now that digital technolo- Energy Commission, expressed concern about gy is enabling commercial realization, however, many vital computational problems whose the time seems right to tell this story. Of equal solutions were beyond the capabilities of exist- interest might be the saga of how a professor ing electronic computers. In his opinion, com- and his graduate students, in an academic set- mercial computer manufacturers had lost ting, can work on one complex problem over a interest in exploring risky, innovative comput- prolonged period and bring to the computer er architectures. Instead, the manufacturers science world original ideas that can them- wanted to serve the growing market for con- selves be commercially realized. -

Db548ts0688.Pdf

1975 Anaheim Convention Center Anaheim, Table.—.--.—of Contents Computer California Conference May 19-22, 1975 General Chairman's Message 3 Technical Program Chairman's Message 4 Keynote Address 6 Conference Luncheon 7 v Special Address 8 Industry Luncheon 9 Harry Goode Memorial Award 10 __,_ Technical Sessions 1975 NATIONAL COMPUTER CONFERENCE Monday Afternoon 11 Sponsored by Tuesday Morning 18 Tuesday Afternoon 26 Tuesday Evening 35 a cmc a r- _, . Wednesday Morning 37 AMPS American Federation of Information Wednesday Afternoon 47 Processing Societies Thursday Morning 60 Thursday Afternoon 69 ACM Association for Computing Machinery Conference At A Glance 52 DPMA Data Processing Management Association Special Activities I pc i eee p„~„ . r. ■ Conference Receptions 78 lEEE-CS lEEE Computer Society Computer Science Fair 78 Computer bUbcr-c o :.*. Science Theatre 78 Society for Computer Simulation NCC Art Show 78 Computer Sound & Light Show 78 apidc __ General Conference Information AFIPS rntioTiTi CONSTITUENT SOCIETIES Conference Proceedings 79 A. AA American Institute of Aeronautics and M^sag^ter ZZZ. ZZZZZZZZZZ. ZZ. ...... Z. £ Astronautics Press Room 79 Room 79 AIPDA a Speaker Lounge, Registration & Practice .... Mii^rA American Institute of Certified Public Information Center 79 Accountants International Visitors Lounge 80 First-Aid Room 80 ASIS American Society for Information Science Ste Recordings- ...ZZZ ZZZ ZZZ ZZZ so ASA American Statistical Association AFIPS Officers and Board of Directors 80 ACL Association for Computational Linguistics NCC Board of Directors National Computer Conference Committee f82n ACM Association for Computing Machinery Industry Advisory Panel 83 AEDS Association for Educational Data Systems 1975 NCC Steering Committee 83 Technical Program Committee 83 Ur-MAnPMA a Data Processing Management Association Technical Program Area Directors 84 lEEE-CS lEEE Computer Society Exhibits Committee 86 , International Committee 86 HA1 1 A . -

Computer Science Department

Henry Samueli School of Engineering & Applied Science Learning the style of recorded motions (MAGIX Lab research program) COMPUTER SCIENCE DEPARTMENT University of California, Los Angeles Fall 2005 Henry Samueli School of Engineering and Applied Science Computer Science Department 4732 Boelter Hall University of California, Los Angeles Los Angeles, CA 90095-1596 Telephone: +1.310.825.3886 Fax: +1.310.825.2273 Email: [email protected] URL: www.cs.ucla.edu Computer Science Department Statistics • Faculty (40) • Graduate Enrollment (280) • M.S. Degrees Awarded (105) • Engineering Degree Awarded (1) • Ph.D. Degrees Awarded (28) • Undergraduate Enrollment (539) • Undergraduate Degrees Awarded (164) The Computer Science Department was formally established during UCLA’s 1968-69 academic year—more than 36 years ago. UCLA is one of the nation's largest and most prestigious graduate education centers in computer and information technology. The dedicated efforts of our prominent faculty and exceptional students have coalesced to rank us among the top computer science departments in the world. The UCLA Computer Science Department is well known for its research in the design and analysis of complex computer systems and networks, and for its key role in the creation of the ARPANET—the precursor to today’s Internet. Internationally recognized research has been carried out in such diverse computer science areas as embedded systems, artificial intelligence, mobile computing, architecture, simulation, graphics, data mining, CAD and reconfigurable systems, biomedical systems, programming languages and compilers. 2 The Computer Science Department has continued to excel in both research and education during the 2003 to 2005 academic years (the period covered in this report). -

V WICSE: a Network of Our Own by Sheila Humphreys

V WICSE: A Network of our Own by Sheila Humphreys It just helped me feel more normal. Kathie Nichols, PhD 1984 WICSE Presidents at the WICSE 40th Anniversary, March 2018, Sutardja-Dai Hall, UC Berkeley Since the 1970s the women’s graduate student organization WICSE (Women in Computer Science and Electrical Engineering) has pursued the goal of increasing the number of women in that discipline and supporting their academic progress. The early days of WICSE were described in Chapter III. WICSE has become a permanent presence in the EECS Department, and, indeed, is the first such group in an American university with a disciplinary focus on computing or electrical engineering in a computer science department.1 The faculty have come to recognize the value of their service to the departmental community and support WICSE with funding. During the 80s, WICSE students worked on graduate recruitment and pressed for hiring women faculty. In that decade twenty-three 1 The national Society of Women Engineers was founded in 1950. UC Berkeley’s student chapter of SWE was founded in 1975. 1 women earned doctoral degrees. Among the distinguished PhD graduates of that decade who were successful at universities and in industry were Barbara Simons, Belle Wei, Teresa Meng, Audrey Viterbi, Susan Eggers and Kathie Nichols.2 One of the organization’s first activities was a reception for “Women in Engineering” at the Women’s Faculty Club in 1979. The WICSE students identified the faculty who were particularly sympathetic to women. Students explained the purpose of what became annual receptions: “The reception has as its purpose to improve the quality of academic life for women students by offering professional role models and the chance to meet and form personal contacts with other engineering students.” At the first reception, Paula Hawthorn, the first President of WICSE, recognized Statistics Professor Elizabeth Scott and two male allies, CS Professor Manuel Blum3 and EE alumnus Dr. -

The 1958 Pekeris-Accad-Weizac Ground-Breaking Collaboration That Computed Ground States of Two-Electron Atoms (And Its 2010 Redux)

THE 1958 PEKERIS-ACCAD-WEIZAC GROUND-BREAKING COLLABORATION THAT COMPUTED GROUND STATES OF TWO-ELECTRON ATOMS (AND ITS 2010 REDUX) CHRISTOPH KOUTSCHAN ∗ AND DORON ZEILBERGER ∗∗ In order to appreciate how well off we mathematicians and scientists are today, with extremely fast hardware and lots and lots of memory, as well as with powerful software, both for numeric and symbolic computation, it may be a good idea to go back to the early days of electronic computers and compare how things went then. We have chosen, as a case study, a problem that was considered a huge challenge at the time. Namely, we looked at C.L. Pekeris's [9] seminal 1958 work1 on the ground state energies of two-electron atoms. We went through all the computations ab initio with today's software and hardware. Schrodinger¨ Let's recall the (time-independent) Schr¨odingerequation for the state function (alias wave func- tion) (x; y; z) of a one-electron atom with a stationary nucleus (see, for example, [8] Eq. (30-1) with N = 1), in atomic units: @2 @2 @2 Z + + + 2 E + (x; y; z) = 0; @x2 @y2 @z2 r where Z denotes the nuclear charge, E the energy of the system, and r = px2 + y2 + z2 the distance of the electron to the nucleus. Schr¨odinger'ssolution of this eigenvalue problem is one of the greatest classics of modern physics, familiar to all physics students (and chemistry students, but unfortunately not math), using sep- aration of (dependent) variables, and getting explicit and exact results for the eigenvalues (the possible energy levels E) and even for the corresponding eigenfunctions . -

The Joy of Philanthropy by Susan Johnson JOY RACHMIL MONKARSH: from BRUIN COED to PHILANTHROPIST

119077_Comp_R1 3/12/04 2:49 PM Page 3 volume seven | number four march 2004 Women & PhilanthropyAT UCLA The Joy of Philanthropy By Susan Johnson JOY RACHMIL MONKARSH: FROM BRUIN COED TO PHILANTHROPIST As befits her name, Joy Monkarsh Joy knows a thing or two about instruction. An education gains happiness by helping others. major, she graduated from UCLA in 1961 (see photo, left) This year marks her tenth anniver- and went on to teach fourth grade in Beverly Hills, as well sary as a UCLA philanthropist, a as serving as a substitute teacher and an at-home teacher for milestone she is delighted to children unable to attend school. She also pursued an inter- celebrate. est in interior design. “So much of what I do today – the But it was her foray into the world of UCLA philanthropy choices I make, how I relate to the that has really energized her. world, even how I feel about myself,” she says, Among the many university projects that she and husband “has been influenced Jerry ’59 support, Joy is especially excited to help sponsor by my work with Dr. James Economou’s gene therapy research in UCLA’s Women & Philanthropy Jonsson Cancer Center. Why Dr. Economou? “His research at UCLA.” in melanomas fascinated me,” Joy states simply, “and I was eager to be a small part of it.” Joy Rachmil, UCLA sopho- Joy was a founding more, as pictured in a 1959 Joy Monkarsh today member of the organi- Initially, her support was extremely structured. “I wanted Look magazine article on zation, which grew from to know exactly what he was working on, where the money California coeds. -

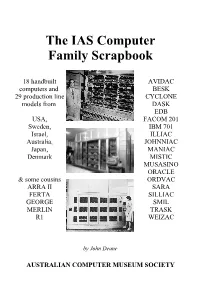

The IAS Computer Family Scrapbook

The IAS Computer Family Scrapbook 18 handbuilt AVIDAC computers and BESK 29 production line CYCLONE models from DASK EDB USA, FACOM 201 Sweden, IBM 701 Israel, ILLIAC Australia, JOHNNIAC Japan, MANIAC Denmark MISTIC MUSASINO ORACLE & some cousins ORDVAC ARRA II SARA FERTA SILLIAC GEORGE SMIL MERLIN TRASK R1 WEIZAC by John Deane AUSTRALIAN COMPUTER MUSEUM SOCIETY The IAS Computer Family Scrapbook by John Deane Front cover: John von Neumann and the IAS Computer (Photo by Alan Richards, courtesy of the Archives of the Institute for Advanced Study), Rand's JOHNNIAC (Rand Corp photo), University of Sydney's SILLIAC (photo courtesy of the University of Sydney Science Foundation for Physics). Back cover: Lawrence Von Tersch surrounded by parts of Michigan State University's MISTIC (photo courtesy of Michigan State University). The “IAS Family” is more formally known as Princeton Class machines (the Institute for Advanced Study is at Princeton, NJ, USA), and they were referred to as JONIACs by Klara von Neumann in her forward to her husband's book The Computer and the Brain. Photograph copyright generally belongs to the institution that built the machine. Text © 2003 John Deane [email protected] Published by the Australian Computer Museum Society Inc PO Box 847, Pennant Hills NSW 2120, Australia Acknowledgments My thanks to Simon Lavington & J.A.N. Lee for your encouragement. A great many people responded to my questions about their machines while I was working on a history of SILLIAC. I have been sent manuals, newsletters, web references, photos, -

Weizmanncasestudysample.Pdf

WWeizmanneizmann AAdd BBookook FFNLNL 0020209-Spreads.pdf20209-Spreads.pdf 1 22/2/09/2/09 99:05:05 AAMM American Committee for the Weizmann Institute of Science American Committee for the Weizmann Institute of Science We are proud to support Global Gathering Gala the Weizmann Institute of Science. Chuck Lorre and Distingushed Guests from the Scientific Community The Three Tenors from Israel Saturday, February 7, 2009 Jubilee Plaza Dorothy Chandler Pavilion Grand Hall Science for the Benef it of Humanity Louis and Cathy Rosenmayer Science for the Benef it of Humanity WWeizmanneizmann AAdd BBookook FFNLNL 0020209-Spreads.pdf20209-Spreads.pdf 2 22/2/09/2/09 99:05:05 AAMM American Committee for the Weizmann Institute of Science American Committee for the Weizmann Institute of Science ScienceS i forf theh BBeneff iit off HHumanityi ScienceS i forf theh BBeneff iit off HHumanityi WWeizmanneizmann AAdd BBookook FFNLNL 0020209-Spreads.pdf20209-Spreads.pdf 3 22/2/09/2/09 99:05:05 AAMM American Committee for the Weizmann Institute of Science American Committee for the Weizmann Institute of Science ScienceS i forfh the BBeneff iit off HHumanityi ScienceS forfh the BBeneff it off HHumanity WWeizmanneizmann AAdd BBookook FFNLNL 0020209-Spreads.pdf20209-Spreads.pdf 4 22/2/09/2/09 99:06:06 AAMM American Committee for the Weizmann Institute of Science American Committee for the Weizmann Institute of Science Chuck Lorre, honoree or the past twenty years, F award-winning creator, executive producer and writer Chuck Lorre has conquered the entertainment industry with hit shows like “Grace Under Fire,” he Three Tenors From Israel is a dazzling trio that has taken Israel and Europe by storm. -

A Tradeoff Study of Switching Systems in Computer Communication Networks

1052 IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTERS, VOL. C-29, NO. 12, DECEMBER 1980 Rami R. Razouk was born in Cairo, Egypt, in Princeton University, where he participated in the 1953. He received the B.S. degree in engineering. design of one of the earliest large digital comput- In 1975 he received the M.S. degree in computer ers. Subsequently, he served as the Director of the science and in 1980 he received the Ph.D. in com- Electronic Computer Project at the Weizmann In- puter architecture, both from the University of stitute of Science, Israel, where he led the develop- California, Los Angeles. ment of WEIZAC, the first large-scale electronic Presently, he is with the Department of Com- computer outside of the United States or Western puter Science, University of California, Los Ange- Europe. In 1956 he became a member of the facul- les. Since 1977 he has led the SARA design group ty at the University of California, Los Angeles and under the direction of Dr. Gerald Estrin. His re- in 1979 received University-wide recognition search interests include modeling, simulation, and analysis of computer sys- when the Regents approved his appointment as an tems. Above Scale Professor. Since July 1979 he has been Chairperson of the UCLA Dr. Razouk is a member of Phi Beta Kappa and Tau Beta Pi. Computer Science Department. He is leading research projects in the com- puter architecture area including the modeling, measurement, and synthesis of computer systems and programs, multilevel simulation of computers, and microprocessor-based networks. Gerald Estrin (S'48-A'51-M'56-F'68) was born in New York, NY. -

UCLA Engineer 2

SPRING 2007 ISSUE NO. 17 Engineer Today’s Seawater is Tomorrow’s Drinking Water: UCLA Engineers Develop Revolutionary Nanotech Water Desalination Membrane Around-the-Clock Healthcare Connecting with High Schools Online Handheld Medical Device Offers at-Home Therapy Virtual Tutoring Boosts Interest in Engineering LETTER FROM THE DEAN The UCLA Henry Samueli School of Engineering and Applied Science has built its reputation through innovative research and high quality education that stresses critical and creative thinking. With the rise of globalization, engineers and scientists in the United States will need to compete on a different level if we are to remain a leader in develop- ment of new technologies. I believe we can do so if we focus on collaborative, interdisciplinary research and education that is truly innovative. Engineer Building on strong tradition of paradigm shifting research, we encourage Dean Vijay K. Dhir our faculty and students to pursue projects with the potential to revolutionize our world, just as the Internet has done. Associate Deans Stephen Jacobsen - Academic and Student Affairs Gregory Pottie - Research and Physical Resources Despite our ambitious goals, however, we are hampered by space and new faculty hiring limitations on campus. To better support the type of ground- Assistant Dean breaking research for which we are known, UCLA Engineering is pursuing Mary Okino - Chief Financial Officer the establishment of an off-site research institute in Southern California. Department Chairs Timothy Deming - Bioengineering Such an institute will allow us to hire additional researchers and to Vasilios Manousiouthakis - Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering William W. G.Yeh - Civil and Environmental Engineering move our research out of the labs and into development and eventually Jason Cong - Computer Science commercialization.