Design for Living Complexities Peter J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

War in the Age of Intelligent Machines

Introduction The image of the ''killer robot" once belonged uniquely to the world of science fiction. This is still so, of course, but only if one thinks of human like mechanical contraptions scheming to conquer the planet. The latest weapons systems planned by the Pentagon, however, offer a less anthropo morphic example of what machines with "predatory capabilities" might be like: pilotless aircraft and unmanned tanks "intelligent" enough to be able to select and destroy their own targets. Although the existing prototypes of robotic weapons, like the PROWLER or the BRAVE 3000, are not yet truly autonomous, these new weapons do demonstrate that even if Artificial Intel ligence is not at present sufficiently sophisticated to create true "killer robots,'' when synthetic intelligence does make its appearance on the planet, there will already be a predatory role awaiting it. The PROWLER, for example, is a small terrestrial armed vehicle, equipped with a primitive form of "machine vision" (the capability to ana lyze the contents of a video frame) that allows it to maneuver around a battlefield and distinguish friends from enemies. Or at least this is the aim of the robot's designers. In reality, the PROWLER still has difficulty negoti ating sharp turns or maneuvering over rough terrain, and it also has poor friend/foe recognition capabilities. For these reasons it has been deployed only for very simple tasks, such as patrolling a military installation along a predefined path. We do not know whether the PROWLER has ever opened fire on an intruder without human supervision, but it is doubtful that as currently designed this robot has been authorized to kill humans on its own. -

Media Ecologies: Materialist Energies in Art and Technoculture, Matthew Fuller, 2005 Media Ecologies

M796883front.qxd 8/1/05 11:15 AM Page 1 Media Ecologies Media Ecologies Materialist Energies in Art and Technoculture Matthew Fuller In Media Ecologies, Matthew Fuller asks what happens when media systems interact. Complex objects such as media systems—understood here as processes, or ele- ments in a composition as much as “things”—have become informational as much as physical, but without losing any of their fundamental materiality. Fuller looks at this multi- plicitous materiality—how it can be sensed, made use of, and how it makes other possibilities tangible. He investi- gates the ways the different qualities in media systems can be said to mix and interrelate, and, as he writes, “to produce patterns, dangers, and potentials.” Fuller draws on texts by Félix Guattari and Gilles Deleuze, as well as writings by Friedrich Nietzsche, Marshall McLuhan, Donna Haraway, Friedrich Kittler, and others, to define and extend the idea of “media ecology.” Arguing that the only way to find out about what happens new media/technology when media systems interact is to carry out such interac- tions, Fuller traces a series of media ecologies—“taking every path in a labyrinth simultaneously,” as he describes one chapter. He looks at contemporary London-based pirate radio and its interweaving of high- and low-tech “Media Ecologies offers an exciting first map of the mutational body of media systems; the “medial will to power” illustrated by analog and digital media technologies. Fuller rethinks the generation and “the camera that ate itself”; how, as seen in a range of interaction of media by connecting the ethical and aesthetic dimensions compelling interpretations of new media works, the capac- of perception.” ities and behaviors of media objects are affected when —Luciana Parisi, Leader, MA Program in Cybernetic Culture, University of they are in “abnormal” relationships with other objects; East London and each step in a sequence of Web pages, Cctv—world wide watch, that encourages viewers to report crimes seen Media Ecologies via webcams. -

2015 Juno Award Nominees

2015 JUNO AWARD NOMINEES JUNO FAN CHOICE AWARD (PRESENTED BY TD) Arcade Fire Arcade Fire Music*Universal Bobby Bazini Universal Drake Cash Money*Universal Hedley Universal Leonard Cohen Columbia*Sony Magic! Sony Michael Bublé Reprise*Warner Nickelback Nickelback II Productions*Universal Serge Fiori GSI*eOne You+Me RCA*Sony SINGLE OF THE YEAR Hold On, We’re Going Home Drake ft. Majid Jordan Cash Money*Universal Crazy for You Hedley Universal Hideaway Kiesza Island*Universal Rude Magic! Sony We’re All in This Together Sam Roberts Band Secret Brain*Universal INTERNATIONAL ALBUM OF THE YEAR PRISM Katy Perry Capitol*Universal Pure Heroine Lorde Universal Midnight Memories One Direction Sony In the Lonely Hour Sam Smith Capitol*Universal 1989 Taylor Swift Big Machine*Universal ALBUM OF THE YEAR (SPONSORED BY MUSIC CANADA) Where I Belong Bobby Bazini Universal Wild Life Hedley Universal Popular Problems Leonard Cohen Columbia*Sony No Fixed Address Nickelback Nickelback II Productions*Universal Serge Fiori Serge Fiori GSI*eOne ARTIST OF THE YEAR Bryan Adams Badman*Universal Deadmau5 Mau5trap*Universal Leonard Cohen Columbia*Sony Sarah McLachlan Verve*Universal The Weeknd The Weeknd XO*Universal GROUP OF THE YEAR Arkells Arkells Music*Universal Chromeo Last Gang*Universal Mother Mother Mother Mother Music*Universal Nickelback Nickelback II Productions*Universal You+Me RCA*Sony BREAKTHROUGH ARTIST OF THE YEAR (SPONSORED BY FACTOR AND RADIO STARMAKER FUND) Glenn Morrison Robbins Entertainment*Sony Jess Moskaluke MDM*Universal Kiesza Island*Universal -

Type Artist Album Barcode Price 32.95 21.95 20.95 26.95 26.95

Type Artist Album Barcode Price 10" 13th Floor Elevators You`re Gonna Miss Me (pic disc) 803415820412 32.95 10" A Perfect Circle Doomed/Disillusioned 4050538363975 21.95 10" A.F.I. All Hallow's Eve (Orange Vinyl) 888072367173 20.95 10" African Head Charge 2016RSD - Super Mystic Brakes 5060263721505 26.95 10" Allah-Las Covers #1 (Ltd) 184923124217 26.95 10" Andrew Jackson Jihad Only God Can Judge Me (white vinyl) 612851017214 24.95 10" Animals 2016RSD - Animal Tracks 018771849919 21.95 10" Animals The Animals Are Back 018771893417 21.95 10" Animals The Animals Is Here (EP) 018771893516 21.95 10" Beach Boys Surfin' Safari 5099997931119 26.95 10" Belly 2018RSD - Feel 888608668293 21.95 10" Black Flag Jealous Again (EP) 018861090719 26.95 10" Black Flag Six Pack 018861092010 26.95 10" Black Lips This Sick Beat 616892522843 26.95 10" Black Moth Super Rainbow Drippers n/a 20.95 10" Blitzen Trapper 2018RSD - Kids Album! 616948913199 32.95 10" Blossoms 2017RSD - Unplugged At Festival No. 6 602557297607 31.95 (45rpm) 10" Bon Jovi Live 2 (pic disc) 602537994205 26.95 10" Bouncing Souls Complete Control Recording Sessions 603967144314 17.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Dropping Bombs On the Sun (UFO 5055869542852 26.95 Paycheck) 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Groove Is In the Heart 5055869507837 28.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Mini Album Thingy Wingy (2x10") 5055869507585 47.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre The Sun Ship 5055869507783 20.95 10" Bugg, Jake Messed Up Kids 602537784158 22.95 10" Burial Rodent 5055869558495 22.95 10" Burial Subtemple / Beachfires 5055300386793 21.95 10" Butthole Surfers Locust Abortion Technician 868798000332 22.95 10" Butthole Surfers Locust Abortion Technician (Red 868798000325 29.95 Vinyl/Indie-retail-only) 10" Cisneros, Al Ark Procession/Jericho 781484055815 22.95 10" Civil Wars Between The Bars EP 888837937276 19.95 10" Clark, Gary Jr. -

Petersen Museum Shifts Into Fast Lane

WWW.PARKLABREANEWS.COM INSIDE • Center for Early Education plans Partly cloudy approved p. 6 with temps in the low 60s Volume 25 No. 50 Serving the Park Labrea and Wilshire Communities December 10, 2015 Fairfax defeats L.A. High forn Div. II championship Hernandez runs for four touchdowns By edwin folven The Fairfax High School varsi- ty football team (8-6) was consid- photo by Gregory Cornfield ered the underdog going into the Expensive vehicles are on display at the Petersen Automotive Museum. Los Angeles City Section Above are cars featured in the “Precious Metal” exhibit. Division II championship game last Saturday against Los Angeles High School (12-1-1). But early in the second quarter, it was apparent the Fairfax High Lions were prepared to challenge Petersen Museum the previously undefeated L.A. High Romans. After turning the ball over on downs during the first n quarter, the Lions started to roar photo by Edwin Folven shiftsAutomotive galleryinto draws fast thousands lane in opening week By GreGory Cornfield behind the nimble feet of senior Fairfax High School running back Ramses Hernandez hoisted the tro- Museum Row with its bright red running back Ramses Hernandez, phy after leading his team to a win in the Los Angeles City Section Div. shell, armored in stainless steel who scored Fairfax High’s first II championship game last Saturday. Before visitors step inside the “ribbons” – a realization of the first touchdown with 9:41 left to go in transformed Petersen Automotive submitted proposal by Kohn the first half. “It’s a great achievement,” work, and it’s something I am Museum, they will see what Pedersen Fox Associates. -

Laptop Performance in Electroacoustic Music: the Current State of Play

Laptop Performance in Electroacoustic Music: The current state of play MMus I. J. Algie 2012 2 Laptop Performance in Electroacoustic Music: The current state of play Ian Algie MMus (Reg No. 090256507) Department of Music April 2012 Abstract This worK explores both the tools and techniques employed by a range of contemporary electroacoustic composers in the live realisation of their worK through a number of case studies. It also documents the design and continued development of a laptop based composition and performance instrument for use in the authors own live performance worK. 3 4 Contents TABLE OF FIGURES ................................................................................................................ 6 PART 1 – WHO IS DOING WHAT WITH WHAT? ............................................................ 7 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 8 SCANNER ................................................................................................................................... 13 HELENA GOUGH ........................................................................................................................ 15 LAWRENCE CASSERLEY ............................................................................................................ 19 PAULINE OLIVEROS .................................................................................................................. 22 SEBASTIAN LEXER ................................................................................................................... -

Remediating Orientation DISSERTATION Presented In

Depth Technology: Remediating Orientation DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Peggy Eileen Reynolds Graduate Program in Comparative Studies The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: Professor Brian Rotman, Advisor Professor Philip Armstrong Professor Barry Shank Copyright by Peggy Eileen Reynolds 2012 Abstract According to sociologist Niklas Luhmann, "The 'blind spot' of each observation, the distinction it employs at the moment, is at the same time its guarantee of a world." To make a distinction, in other words, is to build a world, to establish a boundary, a bounded interior, a self. It is to orient oneself by separating inside from outside and to further the possibilities of one’s persistence by incorporating into this newly formed interior a sign or map of this initial distinction. Tracing the originary orienting gestures of the human and the form these take as sign or map then constitutes the central theme of this dissertation, one which opens onto an exploration of how the new digital economy contributes to the radical reflexivity which characterizes the current material- discursive milieu, even as, by expanding access to the virtual, it increases the potential for an immanent orientation of the human. My method, then, is to investigate the co-constitutive orientation strategies of the human and those forms and patterns which help it construct and distinguish itself from its material-discursive environment. Such forms as grids, circles, hierarchies, vortices, spirals, vortex rings and fractal structures are regarded as little machines; each works in and on the human in unique ways, and each has developed methods to insure its continued survival, collaborating with entities at various scales, including the human, ii to replicate its morphogenetic program. -

Order Form Full

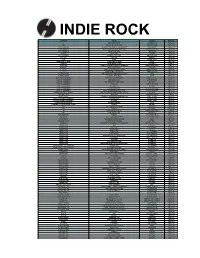

INDIE ROCK ARTIST TITLE LABEL RETAIL 68 TWO PARTS VIPER COOKING VINYL RM128.00 *ASK DISCIPLINE & PRESSURE GROUND SOUND RM100.00 10, 000 MANIACS IN THE CITY OF ANGELS - 1993 BROADC PARACHUTE RM151.00 10, 000 MANIACS MUSIC FROM THE MOTION PICTURE ORIGINAL RECORD RM133.00 10, 000 MANIACS TWICE TOLD TALES CLEOPATRA RM108.00 12 RODS LOST TIME CHIGLIAK RM100.00 16 HORSEPOWER SACKCLOTH'N'ASHES MUSIC ON VINYL RM147.00 1975, THE THE 1975 VAGRANT RM140.00 1990S KICKS ROUGH TRADE RM100.00 30 SECONDS TO MARS 30 SECONDS TO MARS VIRGIN RM132.00 31 KNOTS TRUMP HARM (180 GR) POLYVINYL RM95.00 400 BLOWS ANGEL'S TRUMPETS & DEVIL'S TROMBONE NARNACK RECORDS RM83.00 45 GRAVE PICK YOUR POISON FRONTIER RM93.00 5, 6, 7, 8'S BOMB THE ROCKS: EARLY DAYS SWEET NOTHING RM142.00 5, 6, 7, 8'S TEENAGE MOJO WORKOUT SWEET NOTHING RM129.00 A CERTAIN RATIO THE GRAVEYARD AND THE BALLROOM MUTE RM133.00 A CERTAIN RATIO TO EACH... (RED VINYL) MUTE RM133.00 A CITY SAFE FROM SEA THROW ME THROUGH WALLS MAGIC BULLET RM74.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER BAD VIBRATIONS ADTR RECORDS RM116.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER FOR THOSE WHO HAVE HEART VICTORY RM101.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER HOMESICK VICTORY RECORDS RM101.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER OLD RECORD VICTORY RM101.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER OLD RECORD (PIC) VICTORY RECORDS RM111.00 A DAY TO REMEMBER WHAT SEPARATES ME FROM YOU VICTORY RECORDS RM101.00 A GREAT BIG PILE OF LEAVES HAVE YOU SEEN MY PREFRONTAL CORTEX? TOPSHELF RM103.00 A LIFE ONCE LOST IRON GAG SUBURBAN HOME RM99.00 A MINOR FOREST FLEMISH ALTRUISM/ININDEPENDENCE (RS THRILL JOCKEY RM135.00 A PLACE TO BURY STRANGERS TRANSFIXIATION DEAD OCEANS RM102.00 A PLACE TO BURY STRANGERS WORSHIP DEAD OCEANS RM102.00 A SUNNY DAY IN GLASGOW SEA WHEN ABSENT LEFSE RM101.00 A WINGED VICTORY FOR THE SULLEN ATOMOS KRANKY RM128.00 A.F.I. -

ED302344.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 302 344 PS 017 730 AUTHOR Bauch, Jerold P., Ed. TITLE Early Childhood Education in the Schools. (NEA Aspects of Learning). INSTITUTION National Education Association, Washington, D.C. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8106-1464-2 PUB DATE Sep 88 NOTE 350p. AVAILABLE FROMNational Education Association (NEA) Professional Library, P.O. Box 509, West Haven, CT 06516 ($19.95). PUB TYPE BoOks (010) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Community Involvement; Computer Uses in Education; Discipline; *Early Childhood Education; *Educational History; *Educational Policy; *Educational Trends; Futures (of Society); Parent Participation; *Preschool Education; Program Effectiveness; Program Evaluation; Student Behavior ABSTRACT Collected are 68 articles on a wide raLge of topics related to the education of young children in the schools. Section One offers historical perspectives of early childhood education. Section Two samples policy decisions about present and future issues, especially those with economic, social, and philosophical importance. Section Three explores issues, trends, and directions related to unanswered questions and sources of conflict and choice in early education. Section Four goes to the heart of the issues by focusing on preschool programs. Section Five, which concerns curricul'im issues, aims to provoke thought by exploring what to teach, and why, how, and how not to teach it. Evidence and evaluation are discussed in Section Six, which summarizes some of what is known and what should be evaluated in the future. Section Seven explores both research and common-sense frameworks for thinking about electronic technology, particularly computers, for early childhood programs. Section Eight concerns parent involvement and partnerships between parents and teachers. -

UNIVERSAL MUSIC • the Madden Brothers – Greetings from California • 5 Seconds of Summer – Amnesia (4 Track EP) • Jo

The Madden Brothers – Greetings From California 5 Seconds Of Summer – Amnesia (4 Track EP) John Mellencamp – Plain Spoken New Releases From Classics And Jazz Inside!!! And more… UNI14-35 UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2450 Victoria Park Ave., Suite 1, Willowdale, Ontario M2J 5H3 Phone: (416) 718.4000 Artwork shown may not be final Dear Customer, Effective, immediately, the Canadian distribution of Varese Sarabande Records will change from Outside Music to Universal Music Canada. In order to make this transition as easy as possible for all customers, please note the following steps. ORDERS: Effective, immediately, Outside Music will cancel all back orders for the products listed below. Immediately, Universal Music Canada will solicit all orders and ship the attached product. Product listing with corresponding UMC pricing attached. There are no changes to catalogue or UPC numbers. RETURNS: Universal Music Canada will accept return requests for this product effective, immediately. Credit will be issued per the Universal Music Canada Terms and Conditions of Sale. ADVERTISING: Universal Music Canada will be responsible for ad claims issued after September 1st, 2013. We trust that these procedures will make the transition as smooth as possible and we thank you for your continued support. Please contact your local Universal Music Canada representative should you have any questions. Regards, Adam Abbasakoor Lloyd Nishimura President Vice President, Commercial Affairs Outside Music Universal Music Canada TO CELEBRATE THE 50TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE BEATLES COMING TO CANADA 8/22/1964 Vancouver, British Columbia - Empire Stadium | 9/7/1964 Toronto, Ontario - Maple Leaf Gardens | 9/8/1964 Montreal, Quebec - Montreal Forum Ladies & Gentlemen.. -

Capitalism and Schizophrenia

CAPITALISM AND SCHIZOPHRENIA by Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari Translated from the French by Robert Hurley, Mark Seem, and Helen R. Lane Preface by Michel Foucault University of Minnesota Press Minneapolis Copyright 1983 by the University of Minnesota All rights reserved. Published by the University of Minnesota Press 111 Third Avenue South, Suite 290, Minneapolis, MN 55401-2520 http://www.upress.umn.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper Tenth printing 2000 Originally published as L'Anti-Oedipe © 1972 by Les Editions de Minuit English language translation Copyright © Viking Penguin, 1977 Reprinted by arrangement with Viking Penquin, a division of Penquin Books USA Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Deleuze, Gilles. Anti-Oedipus. Translation of: L'anti-Oedipe. Reprint. Originally published: New York: Viking Press, 1977. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Social psychiatry. 2. Psychoanalysis—Social aspects. 3. Oedipus complex—Social aspects. 4. Capitalism. 5. Schizophrenia—Social aspects. I. Guattari, Felix. II. Title. RC455.D42213 1983 I50.19'52 83-14748 ISBN 0-8166-1225-0 (pbk.) ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Calder and Boyars Ltd.: From Collected Works, Antonin Artaud. City Lights: From "(Caddish" from Kaddish & Other Poems by Allen Ginsberg. Copyright © 1961 by Allen Ginsberg. From Artaud Anthology by Antonin Artaud. Copyright © 1956, 1961, 1965 by Editions Gallimard and City Lights Books. Reprinted by permission of City Lights Books. Humanities Press Inc. and Athlone Press: From Rethinking Anthropology by E. R. Leach. Mercure de France: From Nietzsche ou le Cercle Vicieux by Pierre Klossowski. Pantheon Books, a Division of Random House, Inc.: From Madness and Civilization by Michel Foucauit, translated by Richard Howard. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Derivative Media: The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Derivative Media: The Financialization of Film, Television, and Popular Music, 2004-2016 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Television by Andrew Michael deWaard 2017 © Copyright by Andrew Michael deWaard 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Derivative Media: The Financialization of Film, Television, and Popular Music, 2004-2016 by Andrew Michael deWaard Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Television University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor John T. Caldwell, Chair This dissertation traces the entrance of the financial industries – particularly private equity firms, corporate venture capital, and institutional investors – along with their corresponding financial logic and labor, into the film, television, and music industries from 2004-2016. Financialization – the growing influence of financial markets and instruments – is premised on highly-leveraged debt, labor efficiencies, and short-term profits; this project argues that it is transforming cultural production into a highly consolidated industry with rising inequality, further decreasing the diversity and heterogeneity it could provide the public sphere. In addition to charting this historical and industrial shift, this project analyzes the corresponding textual transformation, in which cultural products behave according to financial logic, becoming sites of capital formation where references, homages, and product placements form internal economies. The concept of ‘derivative media’ I employ to capture this phenomenon contains a double meaning: ii increasingly, the production process of popular culture ‘derives’ new content from old (sequels, adaptations, franchises, remakes, references, homages, sampling, etc.), just as the economic logic behind contemporary textuality behaves like a ‘derivative,’ a financial instrument to hedge risk.