4. Wider Social Determinants of Health

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

High Wycombe a New Vision for HIGH WYCOMBE Centre Square Celebrates the Beginning of an Exciting New Era for High Wycombe

WYCOMBE Apartment living in the heart of High Wycombe A new vision for HIGH WYCOMBE Centre Square celebrates the beginning of an exciting new era for High Wycombe. In a prime position right in the heart of town, this dynamic new collection of studio, one and two bedroom apartments is set to redefine the area. 2 1 Computer generated illustration indicative only Landmark Development The historic market town of High Wycombe is experiencing a renaissance. Around 300 inspirational homes are being created immediately opposite the Eden Centre, as part of a pioneering town centre development by award-winning Inland Homes. Transforming a key brownfield site, this scheme blends stunning new build architecture with the creative refurbishment of existing buildings, to dramatically enhance the town centre and create a real sense of place. Centre Square will bring new homes, shops, leisure amenities and business premises, improve the road layout and create new public spaces, putting High Wycombe firmly on the map as somewhere people want to work, rest and play. Living at Centre Square, you’ll have everything on your doorstep. So whether you’re down-sizing, a young professional, a first-time buyer or an investor, it’s well worth taking a fresh look at High Wycombe. 42 53 Computer generated illustrations indicative only Did you know? In around 150AD the Romans built a villa with a bath-house on the site of The lido on The Rye. Roman bricks from the villa can be seen today in the tower of the church. OLD NEW Already rated highly by the Guild of Property Professionals, High Wycombe’s location on the edge of the Chilterns, combined with its proximity to London – &the fastest trains to the capital can have you in Marylebone in just 26 minutes – guarantee its appeal to commuters. -

Wycombe Air Park Consultation Document

WYCOMBE AIR PARK CONSULTATION DOCUMENT CHANGES TO THE WAY AIRCRAFT APPROACH THE AERODROME 1st MARCH 2017 - 7th JUNE 2017 1 Contents 1. Foreword .......................................................................................................... 3 2. Context ............................................................................................................. 4 3. Executive Summary ........................................................................................... 6 4. Runway Operations ........................................................................................... 8 5. Approach Operations ........................................................................................ 9 6. Consultation Proposal ..................................................................................... 11 7. Consultation Options ...................................................................................... 12 8. Environmental Impacts ................................................................................... 14 9. Consultation Process ....................................................................................... 17 10. How Can Stakeholders Respond? .................................................................... 19 11. Consultation Feedback Form ........................................................................... 20 12. Glossary .......................................................................................................... 21 13. Technical summary ........................................................................................ -

British Waterways Board General Canal Bye-Laws

BRITISH WATERWAYS BOARD GENERAL CANAL BYE-LAWS 1965 BRITISH WATERWAYS BOARD BYE-LAWS ____________________ for regulation of the canals belonging to or under the control of the British Waterways Board (other than the canals specified in Bye-law 1) made pursuant to the powers of the British Transport Commission Act, 1954. (N.B. – The sub-headings and marginal notes do not form part of these Bye-laws). Application of Bye-laws Application of 1. These Bye-laws shall apply to every canal or inland navigation in Bye-Laws England and Wales belonging to or under the control of the British Waterways Board except the following canals: - (a) The Lee and Stort Navigation (b) the Gloucester and Sharpness Canal (c) the River Severn Navigation which are more particularly defined in the Schedule hereto. Provided that where the provisions of any of these Bye-laws are limited by such Bye-law to any particular canal or locality then such Bye-law shall apply only to such canal or locality to which it is so limited. These Bye-laws shall come into operation at the expiration of twenty-eight days after their confirmation by the Minister of Transport as from which date all existing Bye-laws applicable to the canals and inland navigations to which these Bye-laws apply (other than those made under the Explosives Act 1875, and the Petroleum (Consolidation) Act 1928) shall cease to have effect, without prejudice to the validity of anything done thereunder or to any liability incurred in respect of any act or omission before the date of coming into operation of these Bye-laws. -

BUCKINGHAMSHIRE THAMES VALLEY Stimulating the Regeneration and Sustainable Development of Buckinghamshire’S Key Urban Conurbations

USEACT NETWORK BUCKINGHAMSHIRE THAMES VALLEY Stimulating the regeneration and sustainable development of Buckinghamshire’s key urban conurbations Our priorities: Development Finance Employment Growth in key sectors Affordable & Intermediate Housing Leadership and Partnership Alignment ‘Smart’ Infrastructure CONTENTS USEACT PROJECT FRAMEWORK ................................................................................................................. 3 FOREWORD ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 ABOUT USE-ACT .............................................................................................................................................. 4 OUR TEAM ........................................................................................................................................................ 5 SECTION 1: LAP TARGET & CONTEXT ......................................................................................................... 6 STRATEGIC TARGET OF THE LAP (THE MISSION) .................................................................................. 6 THE CONTEXT/ SETTING AND CHALLENGES .......................................................................................... 6 STRATEGIC FIT WITH OTHER LOCAL STRATEGIES, PLANS & ACTIONS ............................................. 7 SECTION 2: LAP DEVELOPMENT ................................................................................................................. -

Evidence Base

BUCKINGHAMSHIRE THAMES VALLEY LEP EVIDENCE BASE FOR THE BTVLEP LOCAL GROWTH FUND & EUROPEAN UNION SIF STRATEGIES (2014 – 2020) VERSION 10.00 Page 1 CONTENTS 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................ 4 1.1 Background ................................................................................................................................................ 4 1.2 Buckinghamshire’s Economic Strengths ..................................................................................................... 5 1.3 Buckinghamshire Economic Weaknesses ................................................................................................... 5 1.4 The Social & Environmental Risks to the Buckinghamshire Economy ......................................................... 6 1.5 BTVLEPs Growth Priorities ......................................................................................................................... 6 2.0 THE BUCKINGHAMSHIRE THAMES VALLEY LEP REGION .............................................................................. 8 2.1 The Buckinghamshire Economy ................................................................................................................. 8 2.2 Important ‘Plan for Growth’ Sectors in Buckinghamshire ............................................................................. 9 2.3 Other sectors important to the Buckinghamshire Economy ......................................................................15 -

Tring and Wigginton

Walk 5 Walk 5 Tring and Wigginton A varied and more challenging walk along undulating chalk hills, through beech to woodlands and back along the Grand Union Canal. The walk follows a section of Aldbury the Ridgeway through Wigginton, one of the highest villages in the Chilterns with P Tring wonderful views. 9 Tring Station Distance: 4¼ miles (allow 2¼ hours) 1 Grand Pendley Manor Start: Tring Station (or the Greyhound Inn, Wigginton, with permission). Union Canal Access Information: There is a moderate climb from the footbridge over the A41 to Wigginton, otherwise the route is relatively level. Refreshments: Both the Cow Roast pub and the Greyhound Inn serve food. 2 Route: A4251 8 Starting from Tring Station, turn left along Lewin's Farm. Follow this across fields and the road over the canal bridge and take the through a wood, (signed Chiltern Way) until Tring Park first turn on your left into Beggars Lane, you reach another footpath at a ‘T’ junction. 3 also signposted the Ridgeway. After about Turn right (signposted ‘Public Footpath to 4 200 yards, take the footpath on your right. 1 Cow Roast’) and down a concrete track to Wigginton Follow Ridgeway signs to reach the A4251 the road. Turn left to go through the tunnel 6 road, crossing over the road at the traffic under the A41, then immediately right along Cow 7 island 2 then over the bridge to cross the a byway to go past Tinker's Lodge on your Roast A41 below. Follow the Ridgeway uphill until left and continue to the A4251 and the Cow PH you reach a lane 'The Twist'; 3 cross over Roast pub, once a stop-off for cattle on their and continue along a footpath until you way to London markets. -

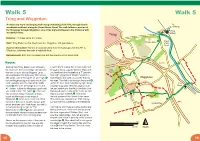

MK Cycling Map a Map of the Redways and Other Cycle Routes in Milton Keynes

MK Cycling Map A map of the Redways and other cycle routes in Milton Keynes www.getcyclingmk.org Stony Stratford A B C Little D Riv E Linford er Great O Nature Haversham Dovecote use Reserve Ouse Valley Park Spinney Qu e W en The H Grand Union Canal a A5 Serpentine te i E r g le L h a se Haversham a n u S Riv t O ne o er Grea Village School t r r e S e tr Burnt t e et Covert Sherington Little M Russell Linford 1 Stony Stratford Street Ouse Valley Park Park L Library i School St Mary and St Giles t t Lakelane l Ousebank C of E Junior School Co e lt L Spinney WOLVERTON s H i ol n m f MILL Road o Old W r Wolverton Ro olv Manor d ad Strat Tr ert ford Road on L ad i R Farm a Lathbury o n oad n R Slated Row i e n t t y Ouse Valley Park to STONY e School g R n e i o r r t Stantonbury STRATFORD a OLD WOLVERTON Haversham e L d h o S Lake y S n r Lake a d o W o n WOLVERTON MILL W d n Portfields e Lathbury a s e lea EAST W s R S s o E Primary School t House s tr R oa at e b C n fo r o hi u e r u ch n e d c rd ele o d The R r O rt u o y swo y H e Q ad n r y il t Radcliffe t l lv R h 1 a i n Lan 1 e v e e Ca School Wolverton A r er P r G Gr v L e eat e v Wyvern Ou a i n R M se Bury Field l A u k il d School l L e e i H din i l y gt a t s f le on A t al WOLVERTON MILL l o n e e G ve C Wolverton L r h G u a L a d venu Queen Eleanor rc i A SOUTH r h Library n n S C Primary School e A tr R Blackhorse fo e H1 at M y ee d - le t iv n r a y sb e Stanton REDHOUSE d o a u r Bradwell o Lake g d R r V6 G i a L ew y The r n Newport n n o g o e Low Park PARK a -

Grand Union Canal Walk

Explore the Colne Valley Park Countryside on your doorstep Points of interest/history 1) The Grand Union Canal was completed in 1805, linking London and the Midlands, and vitally important to Britain’s Industrial CIRCULAR WALK 12: GRAND UNION CANAL Revolution. Denham Deep Lock is so called because at 11 feet it is the deepest on the canal. This was caused by mill owners on the 4 MILES River Frays (passing under the canal at the lock) insisting that the flow on their river was unaffected - hence the long stretch of canal A peaceful stretch of the Grand Union Canal with views over ahead with no lock. John Fray was Baron Lord Chancellor of the magnificent lakes with thriving bird life. Exchequer in the 1400s. He had considerable experience of rivers and mills around London and had a financial interest in Cowley Hall - a property in Hillingdon which adjoins the Frays River. The Frays River is fed by the River Colne at a weir north of Denham Lock. It Access: No steep slopes, but some muddy paths in winter. runs parallel to the Colne for around four miles before rejoining it south of West Drayton. By 1641 the Frays River powered at least 5 Refreshments: Cafes at the Colne Valley Park Visitor Centre (1), mills. The last mill, Fountain's Mill in Uxbridge, was in operation Fran’s Tea Garden at Denham Deep Lock (2), and Widewater Café until after World War Two. on Moorhall Road (3). The Bear on the Barge Pub (A). 2) There are occasional passenger trains from Marylebone to Public transport: By train: Trains from London Marylebone and Denham and beyond. -

Wycombe District Local Plan Settlement Hierarchy Study

Wycombe District Local Plan Settlement Hierarchy Study Final Report June 2016 1 CONTENTS 1. Background 3 2. National policy context 4 3. Methodology 5 4. The resulting hierarchy 9 5. List of settlements considered in the study 15 6. Settlement Audit Matrix 17 7. Map showing settlement hierarchy 20 Appendix A: Local policy context 22 Appendix B: Review of other studies 24 Appendix C: Summary of information sources 28 Appendix D: Glossary of Terms 31 Appendix E: Detailed settlement audits (separate document) 2 1. Background 1.1 Wycombe District Council is currently progressing work on preparing a new planning framework, including a new Local Plan for the District. This work comprises a range of studies to explore options for accommodating new development requirements. 1.2 As part of the Council’s technical work which has already taken place, particularly as part of the Local Plan Options Consultation in 2014, it has already become clear that the requirements for new development are likely to be considerably higher than previous targets. Consequently the Council is likely to be faced with significantly greater challenges in terms of finding options to meet these needs. 1.3 To put this into context, the Council’s Adopted Core Strategy was based on a housing target of 402.5 new homes per annum, a quantum which was capable of being delivered predominantly through brownfield development and the limited pool of greenfield reserve sites in the south of the District. The early indication of significantly higher growth levels in the District means, however, that for the first time in many years, there is the prospect of a significant level of greenfield development being required to be explored in the Local Plan, to help meet the District’s development requirements. -

Grand Union Canal 2014

ROAD Rickmansworth dates back to Saxon times and with its prominent position at the M25 Junc 19 UXBRIDGE ROAD Parsonage A404, M25 Junc 18 confluence of the 3 rivers Chess, Gade & Colne. It grew to a sizeable town gaining its Malvern Way Grand Union Canal Rickmansworth Park RECTORY Track Canal Lock London Underground Fishing Chandler’s Cross Chandler’s Cross Towpath Station Dell Wood A412 JMI School Rickmansworth Station royal charter in 1542. Public / Private (no through road for vehicles) Maple Cross Baldwins Lane Lane Rail and Metropolitan Line, Mill M25 Junc 17 N A412 Rectory Lane The canal was built in 1797, and many businesses sprang up in the vicinity including Gade River / Canal / Lake Grove Road London Underground Rickmansworth Park Bank Cycle Routes (traffic free) Street / Minor Road Car Park Watersports PARK ROAD A412 Lane Walking & Cycling JMI School New Road Barton Way ” proposed A412 5 paper mills and a brewery. Later came the railway to Watford built by Lord Ebury route Langleybury UXBRIDGE ROAD Lodge End Girton Way continues Cycle Route part of the Pub / Restaurant / High Street in 1862 becoming the Ebury Way after the line finally closed in 1981. The state of Main Road Toilet School / College L School Links Way on other National Cycle Network Refreshments an gle Pennsylvania USA is named after a famous former resident William Penn who lived in Dickinson Avenue side ybu A412 ry L Rousebarn a The Grand Union Canal Wensum Basing House - now Three Rivers Museum. Cycle / Pedestrian Crossing Motorway Supermarket / Shop Children’s Play Area Fields ne Cassiobridge Open Land Way StationRickmansworth Road Malvern Way Lock No. -

Report on the Examination of the Wycombe Core Strategy

The Planning Inspectorate Temple Quay House Report to Wycombe 2 The Square Temple Quay Bristol BS1 6PN District Council 0117 372 8000 by Roy Foster MA MRTPI an Inspector appointed by the Secretary of State Date 7th May 2008 for Communities and Local Government PLANNING AND COMPULSORY PURCHASE ACT 2004 SECTION 20 REPORT ON THE EXAMINATION OF THE WYCOMBE CORE STRATEGY DEVELOPMENT PLAN DOCUMENT Document submitted for examination in April 2006 Examination hearings held on 27-29 November and 4-6 & 10-14 December 2007 File Ref: PINS/K0425/429/10 Inspector’s report on the examination of the soundness of Wycombe Core Strategy List of abbreviations used in this report AONB Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty CS Core Strategy DPD Development Plan Document FPEC Further Pre-Examination Change LDF Local Development Framework LDS Local Development Scheme MOD Ministry of Defence PEC Pre-Examination Change PPG2 Planning Policy Guidance Note 2: Green Belts PPG17 Planning Policy Guidance Note 17: Planning for Open Space, Sport and Recreation PPS1 Planning Policy Statement 1: Delivering sustainable development PPS3 Planning Policy Statement 3: Housing PPS6 Planning Policy Statement 6: Planning for Town Centres PPS7 Planning Policy Statement 7: Sustainable development in rural areas PPS9 Planning Policy Statement 9: Biodiversity and Geological Conservation PPS12 Planning Policy Statement 12: Local Development Frameworks PPS25 Planning Policy Statement 25: Development and Flood Risk RPG9 Regional Planning Guidance for the South East RSS Regional Spatial Strategy -

Post-16 Buckinghamshire County Council Travel Policy

Local Authority Post 16 Transport Policy Statement 2017/2018 Transport policy statement for learners aged 16–18 and continuing learners aged 19 and over Name of Local Authority: Buckinghamshire County Council Department Responsible: Children’s Social Care and Learning 1. Summary of Policy Statement and Main Objectives Buckinghamshire County Council is committed to ensuring that students aged 16–19 have access to educational opportunities at school or college, enabling them to acquire the knowledge, skills and experience necessary for them to pursue their chosen careers and, more importantly, to meet the challenge of employment and personal development in the future. This Policy Statement describes the assistance with transport costs that is available to students aged 16-19, resident in Buckinghamshire, who are undertaking full-time further education courses. This statement is published in line with the Department for Education national guidance: www.gov.uk/government/publications/post-16-transport-to-education-and-training 2. Financial Support Schemes 2.1. The 16-19 Bursary Fund A key priority of the Government is to close the gap in attainment between those from poorer and more affluent backgrounds, and to ensure every young person participates in and benefits from a place in 16-19 education and training. The Government provides funding to tackle disadvantage both through the Education Funding Agency’s (EFA) funding formula and through the £180 million 16-19 Bursary Fund to help young people meet the costs of participating in education and training post-16. The scheme is made up of two elements: Bursaries of £1,200 a year are available for the most vulnerable groups.