Airborne for Pleasure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

High Wycombe a New Vision for HIGH WYCOMBE Centre Square Celebrates the Beginning of an Exciting New Era for High Wycombe

WYCOMBE Apartment living in the heart of High Wycombe A new vision for HIGH WYCOMBE Centre Square celebrates the beginning of an exciting new era for High Wycombe. In a prime position right in the heart of town, this dynamic new collection of studio, one and two bedroom apartments is set to redefine the area. 2 1 Computer generated illustration indicative only Landmark Development The historic market town of High Wycombe is experiencing a renaissance. Around 300 inspirational homes are being created immediately opposite the Eden Centre, as part of a pioneering town centre development by award-winning Inland Homes. Transforming a key brownfield site, this scheme blends stunning new build architecture with the creative refurbishment of existing buildings, to dramatically enhance the town centre and create a real sense of place. Centre Square will bring new homes, shops, leisure amenities and business premises, improve the road layout and create new public spaces, putting High Wycombe firmly on the map as somewhere people want to work, rest and play. Living at Centre Square, you’ll have everything on your doorstep. So whether you’re down-sizing, a young professional, a first-time buyer or an investor, it’s well worth taking a fresh look at High Wycombe. 42 53 Computer generated illustrations indicative only Did you know? In around 150AD the Romans built a villa with a bath-house on the site of The lido on The Rye. Roman bricks from the villa can be seen today in the tower of the church. OLD NEW Already rated highly by the Guild of Property Professionals, High Wycombe’s location on the edge of the Chilterns, combined with its proximity to London – &the fastest trains to the capital can have you in Marylebone in just 26 minutes – guarantee its appeal to commuters. -

House of Commons Official Report

Monday Volume 650 26 November 2018 No. 212 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Monday 26 November 2018 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2018 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. HER MAJESTY’S GOVERNMENT MEMBERS OF THE CABINET (FORMED BY THE RT HON. THERESA MAY, MP, JUNE 2017) PRIME MINISTER,FIRST LORD OF THE TREASURY AND MINISTER FOR THE CIVIL SERVICE—The Rt Hon. Theresa May, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE DUCHY OF LANCASTER AND MINISTER FOR THE CABINET OFFICE—The Rt Hon. David Lidington, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE EXCHEQUER—The Rt Hon. Philip Hammond, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE HOME DEPARTMENT—The Rt Hon. Sajid Javid, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR FOREIGN AND COMMONWEALTH AFFAIRS—The Rt. Hon Jeremy Hunt, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EXITING THE EUROPEAN UNION—The Rt Hon. Stephen Barclay, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR DEFENCE—The Rt Hon. Gavin Williamson, MP LORD CHANCELLOR AND SECRETARY OF STATE FOR JUSTICE—The Rt Hon. David Gauke, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR HEALTH AND SOCIAL CARE—The Rt Hon. Matt Hancock, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR BUSINESS,ENERGY AND INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY—The Rt Hon. Greg Clark, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND PRESIDENT OF THE BOARD OF TRADE—The Rt Hon. Liam Fox, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR WORK AND PENSIONS—The Rt Hon. Amber Rudd, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EDUCATION—The Rt Hon. Damian Hinds, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR ENVIRONMENT,FOOD AND RURAL AFFAIRS—The Rt Hon. -

Wycombe Air Park Consultation Document

WYCOMBE AIR PARK CONSULTATION DOCUMENT CHANGES TO THE WAY AIRCRAFT APPROACH THE AERODROME 1st MARCH 2017 - 7th JUNE 2017 1 Contents 1. Foreword .......................................................................................................... 3 2. Context ............................................................................................................. 4 3. Executive Summary ........................................................................................... 6 4. Runway Operations ........................................................................................... 8 5. Approach Operations ........................................................................................ 9 6. Consultation Proposal ..................................................................................... 11 7. Consultation Options ...................................................................................... 12 8. Environmental Impacts ................................................................................... 14 9. Consultation Process ....................................................................................... 17 10. How Can Stakeholders Respond? .................................................................... 19 11. Consultation Feedback Form ........................................................................... 20 12. Glossary .......................................................................................................... 21 13. Technical summary ........................................................................................ -

Inscribed 6 (2).Pdf

Inscribed6 CONTENTS 1 1. AVIATION 33 2. MILITARY 59 3. NAVAL 67 4. ROYALTY, POLITICIANS, AND OTHER PUBLIC FIGURES 180 5. SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 195 6. HIGH LATITUDES, INCLUDING THE POLES 206 7. MOUNTAINEERING 211 8. SPACE EXPLORATION 214 9. GENERAL TRAVEL SECTION 1. AVIATION including books from the libraries of Douglas Bader and “Laddie” Lucas. 1. [AITKEN (Group Captain Sir Max)]. LARIOS (Captain José, Duke of Lerma). Combat over Spain. Memoirs of a Nationalist Fighter Pilot 1936–1939. Portrait frontispiece, illustrations. First edition. 8vo., cloth, pictorial dust jacket. London, Neville Spearman. nd (1966). £80 A presentation copy, inscribed on the half title page ‘To Group Captain Sir Max AitkenDFC. DSO. Let us pray that the high ideals we fought for, with such fervent enthusiasm and sacrifice, may never be allowed to perish or be forgotten. With my warmest regards. Pepito Lerma. May 1968’. From the dust jacket: ‘“Combat over Spain” is one of the few first-hand accounts of the Spanish Civil War, and is the only one published in England to be written from the Nationalist point of view’. Lerma was a bomber and fighter pilot for the duration of the war, flying 278 missions. Aitken, the son of Lord Beaverbrook, joined the RAFVR in 1935, and flew Blenheims and Hurricanes, shooting down 14 enemy aircraft. Dust jacket just creased at the head and tail of the spine. A formidable Vic formation – Bader, Deere, Malan. 2. [BADER (Group Captain Douglas)]. DEERE (Group Captain Alan C.) DOWDING Air Chief Marshal, Lord), foreword. Nine Lives. Portrait frontispiece, illustrations. First edition. -

PLACE and INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZA TIONS INDEX Italicised Page Numbers Refer to Extended Entries

PLACE AND INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZA TIONS INDEX Italicised page numbers refer to extended entries Aachcn, 549, 564 Aegean North Region. Aktyubinsk, 782 Alexandroupolis, 588 Aalborg, 420, 429 587 Akure,988 Algarve. 1056, 1061 Aalst,203 Aegean South Region, Akureyri, 633, 637 Algeciras, I 177 Aargau, 1218, 1221, 1224 587 Akwa Ibom, 988 Algeria, 8,49,58,63-4. Aba,988 Aetolia and Acarnania. Akyab,261 79-84.890 Abaco,178 587 Alabama, 1392, 1397, Al Ghwayriyah, 1066 Abadan,716-17 Mar, 476 1400, 1404, 1424. Algiers, 79-81, 83 Abaiang, 792 A(ghanistan, 7, 54, 69-72 1438-41 AI-Hillah,723 Abakan, 1094 Myonkarahisar, 1261 Alagoas, 237 AI-Hoceima, 923, 925 Abancay, 1035 Agadez, 983, 985 AI Ain. 1287-8 Alhucemas, 1177 Abariringa,792 Agadir,923-5 AlaJuela, 386, 388 Alicante, 1177, 1185 AbaslUman, 417 Agalega Island, 896 Alamagan, 1565 Alice Springs, 120. Abbotsford (Canada), Aga"a, 1563 AI-Amarah,723 129-31 297,300 Agartala, 656, 658. 696-7 Alamosa (Colo.). 1454 Aligarh, 641, 652, 693 Abecbe, 337, 339 Agatti,706 AI-Anbar,723 Ali-Sabieh,434 Abemama, 792 AgboviIle,390 Aland, 485, 487 Al Jadida, 924 Abengourou, 390 Aghios Nikolaos, 587 Alandur,694 AI-Jaza'ir see Algiers Abeokuta, 988 Agigea, 1075 Alania, 1079,1096 Al Jumayliyah, 1066 Aberdeen (SD.), 1539-40 Agin-Buryat, 1079. 1098 Alappuzha (Aleppy), 676 AI-Kamishli AirpoI1, Aberdeen (UK), 1294, Aginskoe, 1098 AI Arish, 451 1229 1296, 1317, 1320. Agion Oras. 588 Alasb, 1390, 1392, AI Khari]a, 451 1325, 1344 Agnibilekrou,390 1395,1397,14(K), AI-Khour, 1066 Aberdeenshire, 1294 Agra, 641, 669, 699 1404-6,1408,1432, Al Khums, 839, 841 Aberystwyth, 1343 Agri,1261 1441-4 Alkmaar, 946 Abia,988 Agrihan, 1565 al-Asnam, 81 AI-Kut,723 Abidjan, 390-4 Aguascalientes, 9(X)-1 Alava, 1176-7 AlIahabad, 641, 647, 656. -

Flying Clubs and Schools

A P 3 IR A PR CR 1 IC A G E FT E S, , YOUR COMPLE TE GUI DE C CO S O U N R TA S C ES TO UK AND OVERSEAS UK clubs TS , and schools Choose your region, county and read down for the page number FLYING CLUBS Bedfordshire . 34 Berkshire . 38 Buckinghamshire . 39 Cambridgeshire . 35 Cheshire . 51 Cornwall . 44 AND SCHOOLS Co Durham . 53 Cumbria . 51 Derbyshire . 48 elcome to your new-look Devon . 44 Dorset . 45 Where To Fly Guide listing for Essex . 35 2009. Whatever your reason Gloucestershire . 46 Wfor flying, this is the place to Hampshire . 40 Herefordshire . 48 start. We’ve made it easier to find a Lochs and Hertfordshire . 37 school and club by colour coding mountains in Isle of Wight . 40 regions and then listing by county – Scotland Kent . 40 Grampian Lancashire . 52 simply use the map opposite to find PAGE 55 Highlands Leicestershire . 48 the page number that corresponds Lincolnshire . 48 to you. Clubs and schools from Greater London . 42 Merseyside . 53 abroad are also listed. Flying rates Tayside Norfolk . 38 are quoted by the hour and we asked Northamptonshire . 49 Northumberland . 54 the schools to include fuel, VAT and base Fife Nottinghamshire . 49 landing fees unless indicated. Central Hills and Dales Oxfordshire . 42 Also listed are courses, specialist training Lothian of the Shropshire . 50 and PPL ratings – everything you could North East Somerset . 47 Strathclyde Staffordshire . 50 Borders want from flying in 2009 is here! PAGE 53 Suffolk . 38 Surrey . 42 Dumfries Northumberland Sussex . 43 The luscious & Galloway Warwickshire . -

70751 064 RAF Brize Norton ACP Consultation Report Draft A-BZN

ERROR! NO TEXT OF SPECIFIED STYLE IN DOCUMENT. RAF Brize Norton Airspace Change Proposal Consultation Feedback Report Document Details Reference Description Document Title RAF Brize Norton Airspace Change Proposal Consultation Feedback Report Document Ref 70751 064 Issue Issue 1 Date 3rd October 2018 Issue Amendment Date Issue 1 3rd October 2018 RAF Brize Norton Airspace Change Proposal | Document Details ii 70751 064 | Issue 1 Executive Summary RAF Brize Norton (BZN) would like to extend thanks to all the organisations and individuals that took the time to participate and provide feedback to the Public Consultation held between 15th December 2017 and 5th April 2018. The Ministry of Defence (MOD) is the Sponsor of a proposed change to the current arrangements and procedures in the immediate airspace surrounding the airport. As the airport operators, and operators of the current Class D Controlled Airspace (CAS), RAF Brize Norton is managing this process on behalf of the MOD. If approved, the proposed change will provide enhanced protection to aircraft on the critical stages of flight in departure and final approach, and will provide connectivity between the RAF Brize Norton Control Zone (CTR) and the UK Airways network. In addition, the Airspace Change will deliver new Instrument Flight Procedures (IFP) utilising Satellite Based Navigation which will futureproof the procedures used at the Station. As part of the Civil Aviation Authority’s (CAA) Guidance on the Application of the Airspace Change Process (Civil Aviation Publication (CAP) 725) [Reference 1], BZN is required to submit a case to the CAA to justify its proposed Airspace Change, and to undertake consultation with all relevant stakeholders. -

Where to Fly Guide & Corporate Member Listing

AAOOPPAA WHERE TO FLY GUIDE & CORPORATE MEMBER LISTING The Pilot Centre Plymouth Flying School Ltd RD Flying Denham Aerodrome t/a Flynqy Pilot Training c/o Parley Golf Centre Denham St Mawgan Parley Uxbridge Newquay Christchurch Middlesex UB9 5DF Cornwall TR8 4RQ Dorset BH23 6BB Tel: 01895 833838 Tel: 01637 861744 Tel: 01258 471983 Fax: 01895 832267 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Website: BEDFORDSHIRE Website: www.pilotcentre.co.uk www.plymouthflyingschool.co.uk Cessna 152 1 Azure Flying Club PA28-161 3 PA28 3 Building 166, Cranfield Airport Cessna 152 5 Cessna 152 2 ESSEX Cranfield Cessna 172 1 Andrewsfield Aviation Ltd Bedfordshire MK43 0AL Cessna 182 1 CUMBRIA Saling Airfield Tel: 01234 758110 Cessna 182RG 1 Stebbing, Dunmow Fax: 01234 758110 Bellanca Citabria 1 Carlisle Flight Training & Aero Club Essex CM6 3TH Website: www.flyazure.com Carlisle Airport Hangar 30 Tel: 01371 856744 Wycombe Air Centre Ltd PA28 180C Cherokee 2 Carlisle Fax: 01371 850955 PA28 160 Warrior 3 Wycombe Air Park Cumbria CA6 4NW E-mail: [email protected] NB: No longer exclusive to Tui Travel Booker, Marlow Tel: 01228 573344 Web: www.andrewsfield.com staff Buckinghamshire SL7 3DR Fax: 01228 573322 Tel: 01494 443737 Email: [email protected] Cessna 152 5 Fax: 01494 465456 Website: www.carlisle-flight-training.com Cessna 172 1 BERKSHIRE Email: [email protected] PA28R Arrow 1 Piper Tomahawk 2 West London Aero Club Website: www.wycombeaircentre.co.uk PA28 Warrior 1 Piper Warrior -

Richard Berliand Flew Martin’S Beech Duchess from Redhill to Iceland for the Journey of a Lifetime

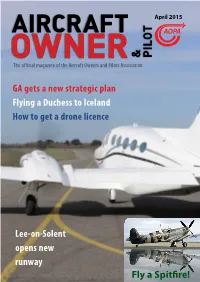

April 2015 AIRCRAFT AOPA OWNER & PILOT The official magazine of the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association GA gets a new strategic plan Flying a Duchess to Iceland How to get a drone licence Lee-on-Solent opens new runway Fly a Spitfire! 2 AIRCRAFT Chairman’s Message OWNER &PILOT Changing Times April 2015 By George Done Editor: Ian Sheppard [email protected] Tel. +44 (0) 7759 455770 In the February issue of General Published by: Aviation I was pleased to announce First Aerospace Media Ltd and welcome Ian Sheppard as the Hangar 9 Redhill Aerodrome Redhill RH1 5JY new editor of the AOPA UK house Tel. +44 (0) 1737 821409 magazine. Ian has taken over from Pat Malone who held the reins for Advertising Office: nearly thirteen years, and contributed AOPA UK hugely to the image and wellbeing of The British Light Aviation Centre the association. 50A Cambridge Street London Sw1V 4QQ When Pat took over the Tel. +44 (0) 20 7834 5631 opportunity was taken to move to bi- monthly publication from quarterly being non-EASA (Annex II) types, Head of Advertising: David Impey and change the title from Light with most being used for private Tel. +44 (0) 7742 605338 Aviation to General Aviation. purposes, this definition covering In the same way, the opportunity use for business reasons and also for Printing: Holbrooks Printers Ltd has been taken with Ian’s editorship recreational and sporting use, as for Articles, photographs and news to take stock and introduce a new a private car. items from AOPA members and other look to the magazine that better A significant proportion of owners readers are welcomed. -

One Day Gliding Courses

ONE DAY GLIDING COURSES ven if you’ve never flown in a glider before, our one day courses will give you an introduction to gliding that you will never forget. E or most people the thought of learning to fly Fhas been a childhood dream that has never been fulfilled. What might surprise you is that learning to fly is not as difficult or as expensive as you may think. At Cotswold Gliding Club we can offer you the opportunity to take to the skies and learn a skill that you will never forget. If you have never experienced gliding before it is an adventure like no other. Once airborne you can savour a unique perspective on the landscape whilst experiencing the thrill and excitement of soaring through the air. “Learning how to fly a glider gave me a sense of freedom and fulfilment like nothing else – I wish I’d done it years ago!” ONE DAY COURSES OFFER: • A day of instruction to teach you the basics of gliding • Gliding in one of the most beautiful parts of England • A chance to experience the thrill and exhilaration of gliding • One of the best gliding facilities in the country • Friendly qualified instructors – there to make your day as enjoyable as possible WHAT IS GLIDING? A glider is the same as a normal aeroplane except that it doesn’t use an engine when it is in flight. Instead, a glider does as you would expect – it glides back to earth but far more efficiently than a normal aeroplane would do. To stay in the air for long periods of time, a glider uses rising air currents. -

SPORTS CLUBS in Swindon

Central SPORTS CLUBS IN Swindon An A-Z of local sports clubs & societies covering a wide range of sporting activities Wiltshire and Swindon Sport www.wiltssport.org.uk 01225 781500 White Horse Business Park, Richmond House, 1 Goodwood Close, Epsom Road, Trowbridge, Wiltshire BA14 0XE Promoting and supporting sport and physical activity to the residents of Wiltshire and Swindon. ANGLING Ashton Keynes Angling Club (coarse fishing) [email protected] www.ashtonkeynesanglingclub.co.uk/ Membership and casual users (day tickets on Neigh Bridge Country Park) Coate Water Fishing Permits www.swindon.gov.uk/info/20077/parks_and_open_spaces/487/coate_water_park/2 01793 490150 You can set up on the bank in the designated fishing areas from 7.30am and purchase a relevant ticket from the ranger on duty when they check the lake. You are allowed to fish until dusk. Day tickets are £5.70 (concessions available). Day Season Permits enable the holder to set up on the bank and fish from 7.30 am until dusk throughout the fishing season. The application form for both types of permit is available to download on the Council website. Day Season permits can be purchased from the Ranger cottage at Coate Water on Fridays between 8.30am - 12noon. You will need to provide a completed Permit Application Form and a valid Fishing Rod Licence. Tickets are £51.50 (concessions available). 24hr Permit Applications (£206.00, concessions available) should be sent to: Mark Jennings, Swindon Borough Council, Wat Tyler House, Beckhampton Street, Swindon SN1 2JH Plaums Angling Club www.plaums-angling-club.co.uk Secretary Gerry Cooper 01793 824327 [email protected] Membership and day tickets. -

Colne Valley | CFA7 | Clevle Valley Colne

LONDON-WEST MIDLANDS ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT ENVIRONMENTAL MIDLANDS LONDON-WEST | Vol 2 Vol LONDON- | Community Forum Area report Area Forum Community WEST MIDLANDS ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT Volume 2 | Community Forum Area report CFA7 | Colne Valley | CFA7 | Colne Valley November 2013 VOL VOL VOL ES 3.2.1.7 2 2 2 London- WEST MIDLANDS ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT Volume 2 | Community Forum Area report CFA7 | Colne Valley November 2013 ES 3.2.1.7 High Speed Two (HS2) Limited has been tasked by the Department for Transport (DfT) with managing the delivery of a new national high speed rail network. It is a non-departmental public body wholly owned by the DfT. A report prepared for High Speed Two (HS2) Limited: High Speed Two (HS2) Limited, Eland House, Bressenden Place, London SW1E 5DU Details of how to obtain further copies are available from HS2 Ltd. Telephone: 020 7944 4908 General email enquiries: [email protected] Website: www.hs2.org.uk High Speed Two (HS2) Limited has actively considered the needs of blind and partially sighted people in accessing this document. The text will be made available in full on the HS2 website. The text may be freely downloaded and translated by individuals or organisations for conversion into other accessible formats. If you have other needs in this regard please contact High Speed Two (HS2) Limited. Printed in Great Britain on paper containing at least 75% recycled fibre. CFA Report – Colne Valley/No 7 | Contents Contents Contents i 1 Introduction 3 1.1 Introduction to HS2 3 1.2 Purpose of this report 3