Evidence Base

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

British Waterways Board General Canal Bye-Laws

BRITISH WATERWAYS BOARD GENERAL CANAL BYE-LAWS 1965 BRITISH WATERWAYS BOARD BYE-LAWS ____________________ for regulation of the canals belonging to or under the control of the British Waterways Board (other than the canals specified in Bye-law 1) made pursuant to the powers of the British Transport Commission Act, 1954. (N.B. – The sub-headings and marginal notes do not form part of these Bye-laws). Application of Bye-laws Application of 1. These Bye-laws shall apply to every canal or inland navigation in Bye-Laws England and Wales belonging to or under the control of the British Waterways Board except the following canals: - (a) The Lee and Stort Navigation (b) the Gloucester and Sharpness Canal (c) the River Severn Navigation which are more particularly defined in the Schedule hereto. Provided that where the provisions of any of these Bye-laws are limited by such Bye-law to any particular canal or locality then such Bye-law shall apply only to such canal or locality to which it is so limited. These Bye-laws shall come into operation at the expiration of twenty-eight days after their confirmation by the Minister of Transport as from which date all existing Bye-laws applicable to the canals and inland navigations to which these Bye-laws apply (other than those made under the Explosives Act 1875, and the Petroleum (Consolidation) Act 1928) shall cease to have effect, without prejudice to the validity of anything done thereunder or to any liability incurred in respect of any act or omission before the date of coming into operation of these Bye-laws. -

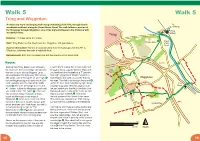

Tring and Wigginton

Walk 5 Walk 5 Tring and Wigginton A varied and more challenging walk along undulating chalk hills, through beech to woodlands and back along the Grand Union Canal. The walk follows a section of Aldbury the Ridgeway through Wigginton, one of the highest villages in the Chilterns with P Tring wonderful views. 9 Tring Station Distance: 4¼ miles (allow 2¼ hours) 1 Grand Pendley Manor Start: Tring Station (or the Greyhound Inn, Wigginton, with permission). Union Canal Access Information: There is a moderate climb from the footbridge over the A41 to Wigginton, otherwise the route is relatively level. Refreshments: Both the Cow Roast pub and the Greyhound Inn serve food. 2 Route: A4251 8 Starting from Tring Station, turn left along Lewin's Farm. Follow this across fields and the road over the canal bridge and take the through a wood, (signed Chiltern Way) until Tring Park first turn on your left into Beggars Lane, you reach another footpath at a ‘T’ junction. 3 also signposted the Ridgeway. After about Turn right (signposted ‘Public Footpath to 4 200 yards, take the footpath on your right. 1 Cow Roast’) and down a concrete track to Wigginton Follow Ridgeway signs to reach the A4251 the road. Turn left to go through the tunnel 6 road, crossing over the road at the traffic under the A41, then immediately right along Cow 7 island 2 then over the bridge to cross the a byway to go past Tinker's Lodge on your Roast A41 below. Follow the Ridgeway uphill until left and continue to the A4251 and the Cow PH you reach a lane 'The Twist'; 3 cross over Roast pub, once a stop-off for cattle on their and continue along a footpath until you way to London markets. -

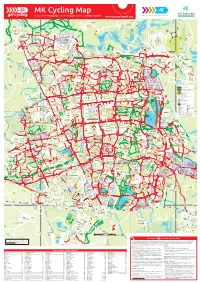

MK Cycling Map a Map of the Redways and Other Cycle Routes in Milton Keynes

MK Cycling Map A map of the Redways and other cycle routes in Milton Keynes www.getcyclingmk.org Stony Stratford A B C Little D Riv E Linford er Great O Nature Haversham Dovecote use Reserve Ouse Valley Park Spinney Qu e W en The H Grand Union Canal a A5 Serpentine te i E r g le L h a se Haversham a n u S Riv t O ne o er Grea Village School t r r e S e tr Burnt t e et Covert Sherington Little M Russell Linford 1 Stony Stratford Street Ouse Valley Park Park L Library i School St Mary and St Giles t t Lakelane l Ousebank C of E Junior School Co e lt L Spinney WOLVERTON s H i ol n m f MILL Road o Old W r Wolverton Ro olv Manor d ad Strat Tr ert ford Road on L ad i R Farm a Lathbury o n oad n R Slated Row i e n t t y Ouse Valley Park to STONY e School g R n e i o r r t Stantonbury STRATFORD a OLD WOLVERTON Haversham e L d h o S Lake y S n r Lake a d o W o n WOLVERTON MILL W d n Portfields e Lathbury a s e lea EAST W s R S s o E Primary School t House s tr R oa at e b C n fo r o hi u e r u ch n e d c rd ele o d The R r O rt u o y swo y H e Q ad n r y il t Radcliffe t l lv R h 1 a i n Lan 1 e v e e Ca School Wolverton A r er P r G Gr v L e eat e v Wyvern Ou a i n R M se Bury Field l A u k il d School l L e e i H din i l y gt a t s f le on A t al WOLVERTON MILL l o n e e G ve C Wolverton L r h G u a L a d venu Queen Eleanor rc i A SOUTH r h Library n n S C Primary School e A tr R Blackhorse fo e H1 at M y ee d - le t iv n r a y sb e Stanton REDHOUSE d o a u r Bradwell o Lake g d R r V6 G i a L ew y The r n Newport n n o g o e Low Park PARK a -

Grand Union Canal Walk

Explore the Colne Valley Park Countryside on your doorstep Points of interest/history 1) The Grand Union Canal was completed in 1805, linking London and the Midlands, and vitally important to Britain’s Industrial CIRCULAR WALK 12: GRAND UNION CANAL Revolution. Denham Deep Lock is so called because at 11 feet it is the deepest on the canal. This was caused by mill owners on the 4 MILES River Frays (passing under the canal at the lock) insisting that the flow on their river was unaffected - hence the long stretch of canal A peaceful stretch of the Grand Union Canal with views over ahead with no lock. John Fray was Baron Lord Chancellor of the magnificent lakes with thriving bird life. Exchequer in the 1400s. He had considerable experience of rivers and mills around London and had a financial interest in Cowley Hall - a property in Hillingdon which adjoins the Frays River. The Frays River is fed by the River Colne at a weir north of Denham Lock. It Access: No steep slopes, but some muddy paths in winter. runs parallel to the Colne for around four miles before rejoining it south of West Drayton. By 1641 the Frays River powered at least 5 Refreshments: Cafes at the Colne Valley Park Visitor Centre (1), mills. The last mill, Fountain's Mill in Uxbridge, was in operation Fran’s Tea Garden at Denham Deep Lock (2), and Widewater Café until after World War Two. on Moorhall Road (3). The Bear on the Barge Pub (A). 2) There are occasional passenger trains from Marylebone to Public transport: By train: Trains from London Marylebone and Denham and beyond. -

Grand Union Canal 2014

ROAD Rickmansworth dates back to Saxon times and with its prominent position at the M25 Junc 19 UXBRIDGE ROAD Parsonage A404, M25 Junc 18 confluence of the 3 rivers Chess, Gade & Colne. It grew to a sizeable town gaining its Malvern Way Grand Union Canal Rickmansworth Park RECTORY Track Canal Lock London Underground Fishing Chandler’s Cross Chandler’s Cross Towpath Station Dell Wood A412 JMI School Rickmansworth Station royal charter in 1542. Public / Private (no through road for vehicles) Maple Cross Baldwins Lane Lane Rail and Metropolitan Line, Mill M25 Junc 17 N A412 Rectory Lane The canal was built in 1797, and many businesses sprang up in the vicinity including Gade River / Canal / Lake Grove Road London Underground Rickmansworth Park Bank Cycle Routes (traffic free) Street / Minor Road Car Park Watersports PARK ROAD A412 Lane Walking & Cycling JMI School New Road Barton Way ” proposed A412 5 paper mills and a brewery. Later came the railway to Watford built by Lord Ebury route Langleybury UXBRIDGE ROAD Lodge End Girton Way continues Cycle Route part of the Pub / Restaurant / High Street in 1862 becoming the Ebury Way after the line finally closed in 1981. The state of Main Road Toilet School / College L School Links Way on other National Cycle Network Refreshments an gle Pennsylvania USA is named after a famous former resident William Penn who lived in Dickinson Avenue side ybu A412 ry L Rousebarn a The Grand Union Canal Wensum Basing House - now Three Rivers Museum. Cycle / Pedestrian Crossing Motorway Supermarket / Shop Children’s Play Area Fields ne Cassiobridge Open Land Way StationRickmansworth Road Malvern Way Lock No. -

Part 2 of 2 Listening to the Grand Union Canal

Part 2 of 2 Listening to the Grand Union Canal Canal Placemaking Listening to the Grand Union Canal A supporting document for the Canal Placemaking Study, 2019, commissioned by the Old Oak and Park Royal Development Corporation (OPDC) with support from Mayor of London. Lead Consultant DK-CM Landscape Architecture Jonathan Cook Landscape Architects Engagement Consultants Spacemakers Graphic Design Consultants Europa @oldoakparkroyal www.london.gov.uk/opdc [email protected] 020 7983 5732 In partnership with Supported by 1 Introduction 5 2 Interviews 9 3 The Canal today 35 3.1 The Grand Union Canal map 36 3.2 Themes and priorities 45 4 The Canal tomorrow 47 5 Acknowledgements 53 LISTENING TO THE GRAND UNION CANAL 1 Introduction 5 1 Introduction What do you love about the Grand Union Canal? What needs to change? What should happen here? In February 2019, the team commissioned by the Old Oak & Park Royal Development Corporation to develop a Canal Placemaking Study set up a floating studio on board a wide beam boat, Jena. They travelled up and down the Paddington Arm of the Grand Union Canal through the study area, asking people exactly these questions. This booklet documents the feedback and answers people gave. The aim was to reach out to regular users of the canal – boaters to cyclists, runners to residents, dog–walkers to workers – to help inform clear visions and proposals for the canal corridor in the years to come. The boat stopped at five sites: Abbey Road Bridge, Harlesden Road Bridge; The Collective on Old Oak Lane, Birchwood Nature Reserve and Mary Seacole Gardens. -

Canal Restrictions by Boat Size

Aire & Calder Navigation The main line is 34.0 miles (54.4 km) long and has 11 locks. The Wakefield Branch is 7.5 miles (12 km) long and has 4 locks. The navigable river Aire to Haddlesey is 6.5 miles (10.4 km) long and has 2 locks. The maximum boat size that can navigate the full main line is length: 200' 2" (61.0 metres) - Castleford Lock beam: 18' 1" (5.5 metres) - Leeds Lock height: 11' 10" (3.6 metres) - Heck Road Bridge draught: 8' 9" (2.68 metres) - cill of Leeds Lock The maximum boat size that can navigate the Wakefield Branch is length: 141' 0" (42.9 metres) beam: 18' 3" (5.55 metres) - Broadreach Lock height: 11' 10" (3.6 metres) draught: 8' 10" (2.7 metres) - cill of Broadreach Lock Ashby Canal The maximum size of boat that can navigate the Ashby Canal is length: There are no locks to limit length beam: 8' 2" (2.49 metres) - Safety Gate near Marston Junction height: 8' 8" (2.64 metres) - Bridge 15a draught: 4' 7" (1.39 metres) Ashton Canal The maximum boat length that can navigate the Ashton Canal is length: 74' 0" (22.5 metres) - Lock 2 beam: 7' 3" (2.2 metres) - Lock 4 height: 6' 5" (1.95 metres) - Bridge 21 (Lumb Lane) draught: 3' 7" (1.1 metres) - cill of Lock 9 Avon Navigation The maximum size of boat that navigate throughout the Avon Navigation is length: 70' (21.3 metres) beam: 12' 6" (3.8 metres) height: 10' (3.0 metres) draught: 4' 0" (1.2 metres) - reduces to 3' 0" or less towards Alveston Weir Basingstoke Canal The maximum size of boat that can navigate the Basingstoke Canal is length: 72' (21.9 metres) beam: 13' -

LOCAL WALKING ROUTES Aylesbury Walks

LOCAL WALKING ROUTES Aylesbury Walks Outer Aylesbury Ring - For a long challenge that can be done in sections there is this walk which is a fully signed route. Some sections can also be walked individually as circular walks and each section has a guide. See here: https://sites.google.com/view/outeraylesburyring/home Aylesbury Ring - A shorter signed route, but still more than most people could do in a day. It could be done in sections, and as it crosses the main radial roads, public transport could be used to get to starting places and from end points. See here: https://www.aylesbury-ramblers.org.uk/the- aylesbury-ring Round Aylesbury Walk - The oldest and shortest of the walks devised by Aylesbury Ramblers. Buckinghamshire Walks: • Weston Turville Reservoir is managed as a nature reserve by Bucks, Berks and Oxfordshire Wildlife Trust (BBOWT) who also have guides to Wild Walks on their reserves. • The Waddesdon Greenway is a flat traffic-free walk from Aylesbury Vale Parkway station to Waddesdon Manor and Waddesdon village. It is about 4km (2.5 miles) each way. • Wendover Woods is a lovely place to walk and has signed walking trails. • The Aylesbury Arm of the Grand Union Canal starting from Aylesbury Canal Basin in the town centre makes a good flat walk to Buckland, Marsworth, Bulbourne or even Tring and Berkhamsted. From Bulbourne there is the option to follow the Wendover Arm of the canal, to Buckland Wharf near Aston Clinton, then Halton and ultimately Wendover. The canal network is managed by the Canal & River Trust which has more information. -

Ton Keynes • Mk11 3Hd

REFURBISHED UNITS 34 - 76 BURNERS LANE NOW AVAILABLE KILN FARM INDUSTRIAL ESTATE • MILTON KEYNES • MK11 3HD TO LET Modern industrial units from 3,758 – 5,286 sq ft (349.12 – 491.08 sq m) • Good access to A5 & M1 Junction 14 • Generous parking & secure yard • 4.9m high loading doors • Minimum internal height 5.4m a r k y P l e a l V s e u O A509 A508 M1 LOCATION TO NORTHAMPTON TO NORTHAMPTON/BIRMINGHAM TO OLNEY NEWPORT Burners Lane is situated off Pitfield at the PAGNELL M1 TO CRANFIELD A5 J15 POTTERS LANE l L a r k heart of the Kiln Farm employment area, n O a TO TOWCESTER a A509 C P N M1 D y H3 76 O se n e o N i n l U eat Ou R Wolverton Station an d O l with easy access to the A5 via Monks Way Gr Gr H4 74 A5 ver A Ri D a A422 14 72 WOLVERTON V9 V H3 H5 STONY 1 (H3). A D H H2 A509 70 e R O STRATFORD O R S T R E E T Willen L A N D s N E O R Lake E E F H6 68 Q U WOLVERTONA T MILL A422 V H4 H5 TO LUTON/LONDON R u T 5 Central Milton Keynes is approximately 5 S TO BUCKINGHAM BURNERS LANE 66 O V5 S 64 A N V4 H3 Q U E E N E L O R A421 S T H7 R CENTRAL V11 E ON KEYNE H6 E T TO BEDFORD 62 minutes drive time and TJunction 14 of the V10 H4 MIL H8 H7 60 V8 A421 34 Milton Keynes Central Station M1 motorway is approximately 10 minutes V7 H8 H9 36 H 13 I V4 G H5 58 H A5 A5130 38 S V T 6 A4146 R KILN FARM H9 E drive time. -

Birmingham Canal Network Fact Sheet Building Cost Locks

Birmingham Canal Network Fact Sheet Birmingham Canal Navigations (BCN) is a network of canals connecting Birmingham, Length: Wolverhampton and the eastern part of the 186 miles Black Country. One of the most intricate canal networks the Building cost world, the Birmingham Canal Navigations (BCN) £50,ooo system, adds up to 1 00 miles over 1 3 canals. History Engineer: The canal network was built over a 100 year James Brindley period starting from 1 772. The canals were the life-blood of Victorian Birmingham and at their height they were so busy that gas lighting was Locks: installed to enable round-the-clock operation. 216 Over eight and a half million tons a year was being carried at the end of the nineteenth century. The canal network serviced the canal Tunnels: side factories and carried raw materials in and products out to the country and world. Map courtesy of Map data 0201 6 Google - attribution Photo courtesy of ahisgett licence - attribution twinkl.co.uk Grand Union Canal Fact Sheet The Grand Union Canal is the longest canal in the UK at 286 miles long and runs from London Length: to Birmingham. 286 miles History The canal was not originally constructed as one canal; it is the result of various canals being amalgamated and Building cost connected during the early 19th century. The canal £772,ooo passes through varied scenery from rolling countryside to industrial towns and cities. Locks: The canal faced competition from the railways 1 66 in the second half of the 19th century. Improvements in roads and vehicle technology in the early part of the 20th century meant that Tunnels: 6 the lorry was also becoming a threat to the canals. -

The Parks Trust Self-Guided Walks: the River Ouse Valley & Cosgrove

The Parks Trust Self-Guided Walks: The River Ouse Valley & Cosgrove Walk revised by Peter Burrett, Monday 3rd June 2013 Start point Travelling north from Old Wolverton towards Haversham along Haversham Road, there is a free parking area on your left at the Ouse Valley Park. Walk overview This is a circular walk, along a footpath and short section of canal towpath via Manor Farm to the Iron Trunk Aqueduct on the Grand Union Canal, then back via a different footpath along the River Ouse. There is also an option to increase the length of your walk by heading north from the Iron Trunk Aqueduct along the Grand Union Canal towpath to the village of Cosgrove and the Barley Mow pub, then retracing your steps back to the Iron Trunk Aqueduct to rejoin the circular walk. Throughout, the walking is easy, along well-maintained hard footpaths, and a canal towpath. Unfortunately, two sets of steep steps must be negotiated, so the walk is not wheelchair friendly. Some of the walk is through the floodplain of the River Ouse so footpaths may be impassable when river levels are high. Distances & times Circular walk, part one; Car park – Manor Farm – Iron Trunk Aqueduct = 1.3 miles, 45 minutes Circular walk, part two; Iron Trunk Aqueduct – River Ouse – car park = 1.3 miles, 35 minutes Total circular walk = 2.6 miles, 80 minutes Cosgrove extended walk option; Iron Trunk Aqueduct – Cosgrove – Iron Trunk Aqueduct = 1.5 miles, 40 minutes. Allow additional time for refreshments at the Barley Mow pub in Cosgrove. Total route PLUS Cosgrove extension = 4.1 miles, 120 minutes The circular walk, part one – car park to Iron Trunk Aqueduct via Manor Farm From the car park, walk through woodland with picnic benches towards the River Ouse and the mighty brick-built Wolverton Viaduct, constructed by Robert Stephenson in 1838. -

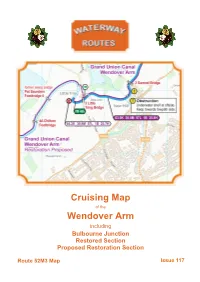

Cruising Map Wendover

Cruising Map of the Wendover Arm including Bulbourne Junction Restored Section Proposed Restoration Section Route 52M3 Map IssueIssue 117 50 Notes 1. The information is believed to be correct at the time of publication but changes are frequently made on the waterways and you should check before relying on this information. 2. We do not update the maps for short term changes such as winter lock closures for maintenance. 3. The information is provides “as is” and the Information Provider excludes all representations, warranties, obligations, and liabilities in relation to the Information to the maximum extent permitted by law. The Information Provider is not liable for any errors or omissions in the Information and shall not be liable for any loss, injury or damage of any kind caused by its use. GGUU 3344 GGUU 3344 DDraytonrayton BBridgeridge 5 GGUU 3333 BBucklanduckland WWharfharf BridgeBridge 55BB 55AA SSaxonaxon LLondonondon RRoadoad BBridgeridge 6 WWayay BBridgeridge WWellonheadellonhead BBridgeridge 7 SSwingwing BBridgeridge GGrandrand UUnionnion CCanalanal WWendoverendover AArmrm RestorationRestoration ProposedProposed 8 HHarelanearelane BBridgeridge GU 32 GGUU 3355 88AA RRothschildothschild BBridgeridge 9 HHaltonalton BBridgeridge 1100 PPercherch BBridgeridge GGrandrand UUnionnion CCanalanal WWendoverendover AArmrm RRestorationestoration PProposedroposed 1111 RRailail CCrossingrossing FFootbridgeootbridge This is the September 2021 edition of the map. See www.waterwayroutes.co.uk/updates for updating to the latest monthly issue at