Aralia Cordata Thunb.)1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPDATED 18Th February 2013

7th February 2015 Welcome to my new seed trade list for 2014-15. 12, 13 and 14 in brackets indicates the harvesting year for the seed. Concerning seed quantity: as I don't have many plants of each species, seed quantity is limited in most cases. Therefore, for some species you may only get a few seeds. Many species are harvested in my garden. Others are surplus from trade and purchase. OUT: Means out of stock. Sometimes I sell surplus seed (if time allows), although this is unlikely this season. NB! Cultivars do not always come true. I offer them anyway, but no guarantees to what you will get! Botanical Name (year of harvest) NB! Traditional vegetables are at the end of the list with (mostly) common English names first. Acanthopanax henryi (14) Achillea sibirica (13) Aconitum lamarckii (12) Achyranthes aspera (14, 13) Adenophora khasiana (13) Adenophora triphylla (13) Agastache anisata (14,13)N Agastache anisata alba (13)N Agastache rugosa (Ex-Japan) (13) (two varieties) Agrostemma githago (13)1 Alcea rosea “Nigra” (13) Allium albidum (13) Allium altissimum (Persian Shallot) (14) Allium atroviolaceum (13) Allium beesianum (14,12) Allium brevistylum (14) Allium caeruleum (14)E Allium carinatum ssp. pulchellum (14) Allium carinatum ssp. pulchellum album (14)E Allium carolinianum (13)N Allium cernuum mix (14) E/N Allium cernuum “Dark Scape” (14)E Allium cernuum ‘Dwarf White” (14)E Allium cernuum ‘Pink Giant’ (14)N Allium cernuum x stellatum (14)E (received as cernuum , but it looks like a hybrid with stellatum, from SSE, OR KA A) Allium cernuum x stellatum (14)E (received as cernuum from a local garden centre) Allium clathratum (13) Allium crenulatum (13) Wild coll. -

New Jan16.2011

Spring 2011 Mail Order Catalog Cistus Nursery 22711 NW Gillihan Road Sauvie Island, OR 97231 503.621.2233 phone 503.621.9657 fax order by phone 9 - 5 pst, visit 10am - 5pm, fax, mail, or email: [email protected] 24-7-365 www.cistus.com Spring 2011 Mail Order Catalog 2 USDA zone: 2 Symphoricarpos orbiculatus ‘Aureovariegatus’ coralberry Old fashioned deciduous coralberry with knock your socks off variegation - green leaves with creamy white edges. Pale white-tinted-pink, mid-summer flowers attract bees and butterflies and are followed by bird friendly, translucent, coral berries. To 6 ft or so in most any normal garden conditions - full sun to part shade with regular summer water. Frost hardy in USDA zone 2. $12 Caprifoliaceae USDA zone: 3 Athyrium filix-femina 'Frizelliae' Tatting fern An unique and striking fern with narrow fronds, only 1" wide and oddly bumpy along the sides as if beaded or ... tatted. Found originally in the Irish garden of Mrs. Frizell and loved for it quirkiness ever since. To only 1 ft tall x 2 ft wide and deciduous, coming back slowly in spring. Best in bright shade or shade where soil is rich. Requires summer water. Frost hardy to -40F, USDA zone 3 and said to be deer resistant. $14 Woodsiaceae USDA zone: 4 Aralia cordata 'Sun King' perennial spikenard The foliage is golden, often with red stems, and dazzling on this big and bold perennial, quickly to 3 ft tall and wide, first discovered in a department store in Japan by nurseryman Barry Yinger. Spikes of aralia type white flowers in summer are followed by purple-black berries. -

Many-Uses-Of-Udo-PM83.Pdf

THE MANY USES FAMILY: Araliaceae CHINESE: Shi Yong Tu Dang Gui ENGLISH: Japanese Asparagus, Udo of FRENCH: Aralie à Feuilles Cordées GERMAN: Japanische Bergangelika JAPANESE: Udo Stephen Barstow invites you to savour a remarkableU DOwild edible, Udo ralia cordata or udo is grown in many countries and deserves to be much more popular in the West. For what is basically Aa wild plant, it is remarkably productive, and the highest yielding vegetable that I have grown. It is a herbaceous perennial reaching 3m (9.8ft) tall in the course of the summer months. It is a close relative of ginseng (Panax ginseng) and is in fact some- times used as a substitute for the latter. There are about eight herbaceous Aralia species restricted to North America and Asia. Udo is wild-foraged in Japan, Korea and China but so popular in Japan that it is now cultivated. Author Joy Larkcom stumbled on cultivated plants in a market in Tokyo in the 1990s whilst researching her book, Oriental Vegetables, describing them as 60cm (23in) long with white stalks. Behind Larkcom’s blanched udo stalks lies a very unusual production method. So-called Nanpaku-udo, or simply Tokyo-udo, is cultivated mainly under- ground beneath Western Tokyo (Tachikawa and Kokubunji City). The roots are forced during the winter months in naturally warm subterranean caverns excavated in the special Kanto loam, of volcanic origin, which can be excavated without danger of collapse. These caverns were originally used to store vegetables, but have been used for forcing udo off-season since about 1927. A pit is first dug 3-4m (9.8-13ft) deep and then several horizontal tunnels are excavated from the bottom of the pit. -

Araliaceae.Pdf

ARALIACEAE 五加科 wu jia ke Xiang Qibai (向其柏 Shang Chih-bei)1; Porter P. Lowry II2 Trees or shrubs, sometimes woody vines with aerial roots, rarely perennial herbs, hermaphroditic, andromonoecious or dioecious, often with stellate indumentum or more rarely simple trichomes or bristles, with or without prickles, secretory canals pres- ent in most parts. Leaves alternate, rarely opposite (never in Chinese taxa), simple and often palmately lobed, palmately compound, or 1–3-pinnately compound, usually crowded toward apices of branches, base of petiole often broad and sheathing stem, stipules absent or forming a ligule or membranous border of petiole. Inflorescence terminal or pseudo-lateral (by delayed development), um- bellate, compound-umbellate, racemose, racemose-umbellate, or racemose-paniculate, ultimate units usually umbels or heads, occa- sionally racemes or spikes, flowers rarely solitary; bracts usually present, often caducous, rarely foliaceous. Flowers bisexual or unisexual, actinomorphic. Pedicels often jointed below ovary and forming an articulation. Calyx absent or forming a low rim, some- times undulate or with short teeth. Corolla of (3–)5(–20) petals, free or rarely united, mostly valvate, sometimes imbricate. Stamens usually as many as and alternate with petals, sometimes numerous, distinct, inserted at edge of disk; anthers versatile, introrse, 2- celled (or 4-celled in some non-Chinese taxa), longitudinally dehiscent. Disk epigynous, often fleshy, slightly depressed to rounded or conic, sometimes confluent with styles. Ovary inferior (rarely secondarily superior in some non-Chinese taxa), (1 or)2–10(to many)-carpellate; carpels united, with as many locules; ovules pendulous, 2 per locule, 1 abortive; styles as many as carpels, free or partially united, erect or recurved, or fully united to form a column; stigmas terminal or decurrent on inner face of styles, or sessile on disk, circular to elliptic and radiating. -

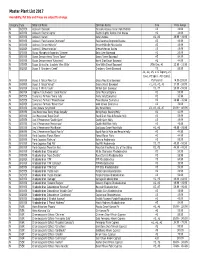

Master Plant List 2017.Xlsx

Master Plant List 2017 Availability, Pot Size and Prices are subject to change. Category Type Botanical Name Common Name Size Price Range N BREVER Azalea X 'Cascade' Cascade Azalea (Glenn Dale Hybrid) #3 49.99 N BREVER Azalea X 'Electric Lights' Electric Lights Double Pink Azalea #2 44.99 N BREVER Azalea X 'Karen' Karen Azalea #2, #3 39.99 - 49.99 N BREVER Azalea X 'Poukhanense Improved' Poukhanense Improved Azalea #3 49.99 N BREVER Azalea X 'Renee Michelle' Renee Michelle Pink Azalea #3 49.99 N BREVER Azalea X 'Stewartstonian' Stewartstonian Azalea #3 49.99 N BREVER Buxus Microphylla Japonica "Gregem' Baby Gem Boxwood #2 29.99 N BREVER Buxus Sempervirens 'Green Tower' Green Tower Boxwood #5 64.99 N BREVER Buxus Sempervirens 'Katerberg' North Star Dwarf Boxwood #2 44.99 N BREVER Buxus Sinica Var. Insularis 'Wee Willie' Wee Willie Dwarf Boxwood Little One, #1 13.99 - 21.99 N BREVER Buxus X 'Cranberry Creek' Cranberry Creek Boxwood #3 89.99 #1, #2, #5, #15 Topiary, #5 Cone, #5 Spiral, #10 Spiral, N BREVER Buxus X 'Green Mountain' Green Mountain Boxwood #5 Pyramid 14.99-299.99 N BREVER Buxus X 'Green Velvet' Green Velvet Boxwood #1, #2, #3, #5 17.99 - 59.99 N BREVER Buxus X 'Winter Gem' Winter Gem Boxwood #5, #7 59.99 - 99.99 N BREVER Daphne X Burkwoodii 'Carol Mackie' Carol Mackie Daphne #2 59.99 N BREVER Euonymus Fortunei 'Ivory Jade' Ivory Jade Euonymus #2 35.99 N BREVER Euonymus Fortunei 'Moonshadow' Moonshadow Euonymus #2 29.99 - 35.99 N BREVER Euonymus Fortunei 'Rosemrtwo' Gold Splash Euonymus #2 39.99 N BREVER Ilex Crenata 'Sky Pencil' -

Mountain Gardens Full Plant List 2016

MOUNTAIN GARDENS BARE ROOT PLANT SALES WWW.MOUNTAINGARDENSHERBS.COM Here is our expanded list of bare root plants. Prices are $4-$5 as indicated. Note that some are only available in spring or summer, as indicated; otherwise they are available all seasons. No price listed = not available this year. We begin responding to requests in April and plants are generally shipped in May and June, though inquiries are welcome throughout the growing season. We ship early in the week by Priority Mail. For most orders, except very large or very small, we use flat rate boxes @$25 per shipment. Some species will sell out – please list substitutes, or we will refund via Paypal or a check. TO ORDER, email name/number of plants wanted & your address to [email protected] Payment: Through Paypal, using [email protected]. If you prefer, you can mail your order with a check (made out to ‘Joe Hollis’) to 546 Shuford Cr. Rd., Burnsville, NC 28714. Or you can pick up your plants at the nursery (please send your order and payment with requested pick-up date in advance). * Shipping & handling: 25$ flat rate on all but very small or very large orders – will verify via email. MOUNTAIN GARDENS PLANT LIST *No price listed = not available this year. LATIN NAME COMMON NAME BARE USE/CATEGORY ROOT Edible, Medicinal, etc. Achillea millefolium Yarrow $4.00 Medicinal Aconitum napellus Monkshood, Chinese, fu zi ChinMed, Ornamental Acorus calamus Calamus, sweet flag Med Acorus gramineus shi chang pu 4 ChinMed Actaea racemosa Black Cohosh 4 Native Med Aegopodium podograria -

Screening of Crude Drugs Used in Japanese Kampo Formulas for Autophagy-Mediated Cell Survival of the Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cell Line

Medicines 2019, 6, 63; doi:10.3390/medicines6020063 S1 of S6 Supplementary Materials: Screening of Crude Drugs Used in Japanese Kampo Formulas for Autophagy-Mediated Cell Survival of the Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cell Line Shinya Okubo, Hisa Komori, Asuka Kuwahara, Tomoe Ohta, Yukihiro Shoyama and Takuhiro Uto Table S1. List of crude drugs. Drug Japanese Name English Name Scientific Name Medicinal Part No. 1 Akyo Donkey Glue Equus asinus glue 2 Ireisen Clematis Root Clematis chinensis, C. mandshurica, C. hexapetala root with rhizome 3 Inchinko Artemisia Capillaris Flower Artemisia capillaris capitulum 4 Uikyo Fennel Foeniculum vulgare fruit 5 Uzu a) Aconite Root Aconitum carmichaeli, A. japonicum tuberous root (mother root) 6 Uyaku Lindera Root Lindera strychnifolia root 7 Engosaku Corydalis Tuber Corydalis turtschaninovii tuber 8 Ogi Astragalus Root Astragalus membranaceus, A. mongholicus root 9 Ogon Scutellaria Root Scutellaria baicalensis root 10 Obaku Phellodendron Bark Phellodendron amurense, P. chinense bark 11 Oren Coptis Rhizome Coptis japonica, C. chinensis, C. deltoidea, C. teeta rhizome 12 Onji Polygala Root Polygala tenuifolia root or root bark 13 Gaiyo Artemisia Leaf Artemisia princeps, A. montana leaf and twig 14 Kashi Myrobalan Fruit Terminalia chebula fruit 15 Kashu Polygonum Root Polygonum multiflorum root 16 Gajutsu Zedoary Curcuma zedoaria rhizome 17 Kakko Pogostemon Herb Pogostemon cablin aerial part 18 Kakkon Pueraria Root Pueraria lobata root 19 Kasseki Aluminum Silicate Hydrate with Silicon Dioxide 20 Karokon Trichosanthes Root Trichosanthes kirilowii, T. kirilowii var. japonica, T. bracteata root Medicines 2019, 6, 63; doi:10.3390/medicines6020063 S2 of S6 21 Karonin Trichosanthes Seed Trichosanthes kirilowii, T. kirilowii var. japonica, T. -

An Encyclopedia of Shade Perennials This Page Intentionally Left Blank an Encyclopedia of Shade Perennials

An Encyclopedia of Shade Perennials This page intentionally left blank An Encyclopedia of Shade Perennials W. George Schmid Timber Press Portland • Cambridge All photographs are by the author unless otherwise noted. Copyright © 2002 by W. George Schmid. All rights reserved. Published in 2002 by Timber Press, Inc. Timber Press The Haseltine Building 2 Station Road 133 S.W. Second Avenue, Suite 450 Swavesey Portland, Oregon 97204, U.S.A. Cambridge CB4 5QJ, U.K. ISBN 0-88192-549-7 Printed in Hong Kong Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Schmid, Wolfram George. An encyclopedia of shade perennials / W. George Schmid. p. cm. ISBN 0-88192-549-7 1. Perennials—Encyclopedias. 2. Shade-tolerant plants—Encyclopedias. I. Title. SB434 .S297 2002 635.9′32′03—dc21 2002020456 I dedicate this book to the greatest treasure in my life, my family: Hildegarde, my wife, friend, and supporter for over half a century, and my children, Michael, Henry, Hildegarde, Wilhelmina, and Siegfried, who with their mates have given us ten grandchildren whose eyes not only see but also appreciate nature’s riches. Their combined love and encouragement made this book possible. This page intentionally left blank Contents Foreword by Allan M. Armitage 9 Acknowledgments 10 Part 1. The Shady Garden 11 1. A Personal Outlook 13 2. Fated Shade 17 3. Practical Thoughts 27 4. Plants Assigned 45 Part 2. Perennials for the Shady Garden A–Z 55 Plant Sources 339 U.S. Department of Agriculture Hardiness Zone Map 342 Index of Plant Names 343 Color photographs follow page 176 7 This page intentionally left blank Foreword As I read George Schmid’s book, I am reminded that all gardeners are kindred in spirit and that— regardless of their roots or knowledge—the gardening they do and the gardens they create are always personal. -

Writing Plant Names

Writing Plant Names 06-09-2020 Nomenclatural Codes and Resources There are two international codes that govern the use and application of plant nomenclature: 1. The International Code of Nomenclature for Algae, Fungi, and Plants, Shenzhen Code, 2018. International Association for Plant Taxonomy. Abbreviation: ICN • Serves the needs of science by setting precise rules for the application of scientific names to taxonomic groups of algae, fungi, and plants • Available online at https://www.iapt-taxon.org/nomen/main.php 2. The International Code of Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants, 9th Edition, 2016. International Association for Horticultural Science. Abbreviation: ICNCP • Serves the applied disciplines of horticulture, agriculture, and forestry by setting rules for the naming of cultivated plants • Available online at https://www.ishs.org/sites/default/files/static/ScriptaHorticulturae_18.pdf These two resources, while authoritative, are very technical and are not easy to read. Two more accessible references are: 1. Plant Names: A guide to botanical nomenclature, 3rd Edition, 2007. Spencer, R., R. Cross, P. Lumley. CABI Publishing. • Hard copy available for reference in the Overlook Pavilion office 2. The Code Decoded, 2nd Edition, 2019. Turland, N. Advanced Books. • Available online at https://ab.pensoft.net/book/38075/list/9/ This document summarizes the rules presented in the above references and, where presentation is a matter of preference rather than hard-and-fast rules (such as with presentation of common names), establishes preferred presentation for the Arboretum at Penn State. Page | 1 Parts of a Name The diagram below illustrates the overall structure of a plant name. Each component, its variations, and its preferred presentation will be addressed in the sections that follow. -

The Taxonomic Status of Aralia Cordata Var. Sachalinensis (Araliaceae)

October 2015 The Journal of Japanese Botany Vol. 90 No. 5 349 J. Jpn. Bot. 90: 349–350 (2015) Hiroyoshi OHASHI: The Taxonomic Status of Aralia cordata var. sachalinensis (Araliaceae) Herbarium TUS, Botanical Gardens, Tohoku University, Sendai, 980-0862 JAPAN E-mail: [email protected] S u m m a r y : Aralia cordata Thunb. var. character is within variation range of the species. sachalinensis (Regel) Nakai should be included in Characters adopted by Regel are useless for the typical form, var. cordata as a synonym. circumscription of the variety. Nakai found a form with pubescent calyces Aralia cordata Thunb. was described from as a diagnostic character distinguishing it from Japan and is distributed widely in East Asia. The the typical form. Aralia cordata has, however, northern form has often been recorded as var. an always tomentose pedicel, and flowers with sachalinensis (Regel) Nakai. The variety was the calyx glabrous or sometime pubescent when described by Regel (1864) as “A. racemosa β. younger. Features of the calyx-tube are kept in sachalinensis Rgl.; robustior, floribus plerumque mature flowers and young fruits. Mature fruits hexameris” and illustrated (Fig. 432) a flowering are all entirely glabrous. When the calyx-tube is branch with an enlarged young fruit (as “a”) pubescent, density of the pubescence is scarce, and flower (as “b”). Regel (1864) did not cite and never densely hairy as in the pedicel. The any specimens for var. sachalinensis in the calyces of Aralia cordata are generally glabrous protologue. or sometimes scarcely pubescent. Nakai (1924) newly characterized the variety The species is distributed in Sakhalin, that “the variety sachalinensis differs from the Kuriles, Hokkaido, Honshu, Shikoku, Kyushu, type [i.e., var. -

Plant Anthocyanins: Biosynthesis, Bioactivity and in Vitro Production from Tissue Cultures

Review Article Adv Biotech & Micro Volume 5 Issue 5 - August 2017 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Archana Mathur DOI: 10.19080/AIBM.2017.05.555672 Plant Anthocyanins: Biosynthesis, Bioactivity and in vitro Production from tissue cultures Tanya Biswas and Archana Mathur* Plant Biotechnology Division, Central Institute of Medicinal & Aromatic Plants, India Submission: July 26, 2017; Published: August 24, 2017 *Corresponding author: Industrial Research, PO CIMAP, Lucknow-226015, India, Tel: ; Fax: ; Email: Archana Mathur, Plant Biotechnology Division, Central Institute of Medicinal & Aromatic Plants, Council of Scientific & Abstract Anthocyanins are a major class of colorful plant pigments, with the exception of chlorophylls, that have long attracted the attention of chemists and biologists, investigating their biosynthesis patterns, metabolism and physiological roles. Belonging to the group of “flavonoids”, maintenance.these anthocyanins Due to accumulated their immense in importancethe vacuoles, as are dietary mainly neutraceuticals, responsible for enhanced the bright production and distinct of these coloration anthocyanins to fruits, from vegetables cell/tissue and culturesflowers. Besides attracting pollinators, this particular class of compounds is often considered as potent “anti-oxidants”, largely impacting human health biosynthesis, in vivo in vitro production of anthocyanins. have been extensively explored since the last 2 decades. This review summarizes the different types of anthocyanins, their basic chemistry and Keywords: Anthocyanin; bioactivities Flavonoid; and Phenylalanine; concludes with Cardio collation protection; of major Elicitationreports regarding Introduction components of plant photosystems. Anthocyanins are believed Anthocyanins, one of the most important plant metabolites, to be functioning as photo protective pigments for the plant, are a group of naturally occurring pigments responsible for red- and preventing oxidative damage. -

Aralia 'Sun King' Brings a Bold Pop of Glowing Color and Texture - the Perfect Anchor for the Shade to Shade-To-Part-Shade Border

PERENNIAL PLANT 2020 OF THE YEAR® ARALIA ‘SUN KING’ BEHOLD, THE SUN KING! No, not Louis XIV of France, rather, a fabulous high-impact perennial. Aralia 'Sun King' brings a bold pop of glowing color and texture - the perfect anchor for the shade to shade-to-part-shade border. "Discovered" by plantsman Barry Yinger in a Japanese garden center (atop a department store), this perennial has become a beloved shade garden staple across the country. Bright yellow shoots emerge in spring, then grow up, up, up...can reach 6' tall and nearly as wide. The small, cream-colored umbels of flowers are attractive to bees and are followed by tiny dark (inedible) drupes. Despite the Sun King’s stature, it's very well behaved – little to no reseeding or suckering. PHOTOS COURTESY OF PHOTO COURTESY OF WALTERS GARDENS, INC. PAUL WESTERVELT PHOTO COURTESY OF DR. DAVID SANFORD PHOTO COURTESY OF JANET DRAPER HARDINESS USDA Zones 3 to 9 LIGHT Part shade to full shade. A few hours of sun brings out the yellow; tends to be more chartreuse in deeper shade. SOIL Not picky - but can flag during dry spells, so provide additional water as necessary. USES Terrific in combination with hosta, ferns, and past PPOY stars such as Polygonatum odoratum ‘Variegatum’ (2013) and Brunnnera macrophylla ‘Jack Frost’ (2012). A knockout when placed near Acer palmatum ‘Bloodgood’ or other maroon-leaf woody. And don’t forget containers - Sun King is bold and beautiful in a big pot! UNIQUE QUALITIES Bold, gold, compound foliage is deer resistant. Bigger than your average perennial, Sun King is frequently described as 4’ tall and as wide, once established, but 6’ tall is not unusual for older plants.